Guide to Udder Health for Dairy Goats - Providing Guidance for Veterinarians and Producers in Improving Milk Quality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mammary Gland

Mammary Gland Suporn Katawatin Department of Animal Science Khon Kaen University Question - Why do cows have four mammary glands? Click here Why4.doc Mammary gland Gland anatomy Circulatory system Lymphatic system Nervous system Gross anatomy: cow model To achieve functional capacity of mammary gland, a number of supporting systems must exist Physical support of the udder mass - Suspensory system On/off valve for intermittent removal of milk - Teat Pathway for milk to travel from the milk synthesis site to the exit - Ducts & Cisterns Means of actively expelling milk from the udder - Neural system Continuous supply of substrates for milk synthesis - Blood system Means of balancing the fluid dynamics in the tissue - Lymph system Internal secretory tissue - Lobes/lobules/alveoli Suspensory system: Physical support of the udder mass median suspensory ligament most important part of the suspensory system in cattle partially separates the left and right halves of the udder great tensile strength, able to stretch, allow increased weight of gland located at center of gravity of the udder to give balanced suspension Suspensory system There are seven tissues that provide support for the udder: Suspensory system.doc Teat : On/off valve for intermittent removal of milk only exit for secretion from gland and for calf to receive milk one teat one gland no hair, sweat glands or sebacious glands size and shape are independent of the size, shape or milk production of the udder average size (cow model) fore teats 6.6 cm long and -

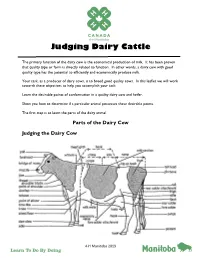

Judging Dairy Cattle

Judging Dairy Cattle The primary function of the dairy cow is the economical production of milk. It has been proven that quality type or form is directly related to function. In other words, a dairy cow with good quality type has the potential to efficiently and economically produce milk. Your task, as a producer of dairy cows, is to breed good quality cows. In this leaflet we will work towards these objectives to help you accomplish your task. Learn the desirable points of conformation in a quality dairy cow and heifer. Show you how to determine if a particular animal possesses these desirable points. The first step is to learn the parts of the dairy animal. Parts of the Dairy Cow Judging the Dairy Cow 4-H Manitoba 2019 Once you know the parts of the body, the next step to becoming a successful dairy judge is to learn what the ideal animal looks like. In this section, we will work through the parts of a dairy cow and learn the desirable and undesirable characteristics. Holstein Canada has developed a scorecard which places relative emphasis on the six areas of importance in the dairy cow. This scorecard is used by all dairy breeds in Canada. The Holstein Cow Scorecard uses these six areas: 1. Frame / Capacity 2. Rump 3. Feet and Legs 4. Mammary System 5. Dairy Character When you judge, do not assign numerical scores. Use the card for relative emphasis only. When cows are classified by the official breed classifiers, classifications and absolute scores are assigned. 2 HOLSTEIN COW SCORE CARD 18 1. -

Of the DEPARTMENT of ZOOLOGY 3H P a Rtia L F

Dental caries in mammals as related to diet and tooth crown structure Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Negley, Henry Hull, 1937- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 04:31:51 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319286 DENTAL CARIES IN M SM ^S AS RELATED TO DIET AND TOOTH CROI® STRUCTURE . by Harry. H.0 Negley^ III A Thesis g'ubmitted to the Facial^- of the DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY 3h Partial FulfilM ent of the Requirements For the Degree of MAST® OF SCIENCE ' 3h th e Graduate,: College THE UNIWRSITf OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

From Birth to Colostrum: Early Steps Leading to Lamb Survival Raymond Nowak, Pascal Poindron

From birth to colostrum: early steps leading to lamb survival Raymond Nowak, Pascal Poindron To cite this version: Raymond Nowak, Pascal Poindron. From birth to colostrum: early steps leading to lamb survival. Reproduction Nutrition Development, EDP Sciences, 2006, 46 (4), pp.431-446. 10.1051/rnd:2006023. hal-00900627 HAL Id: hal-00900627 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00900627 Submitted on 1 Jan 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 46 (2006) 431–446 431 c INRA, EDP Sciences, 2006 DOI: 10.1051/rnd:2006023 Review From birth to colostrum: early steps leading to lamb survival Raymond N*, Pascal P Laboratoire de Comportements, Neurobiologie et Adaptation, UMR 6175 CNRS-INRA-Université François Rabelais-Haras Nationaux, Unité de Physiologie de la Reproduction et des Comportements, INRA, 37380 Nouzilly, France Abstract – New-born lambs have limited energy reserves and need a rapid access to colostrum to maintain homeothermy and survive. In addition to energy, colostrum provides immunoglobulins which ensure passive systemic immunity. Therefore, getting early access to the udder is essential for the neonate. The results from the literature reviewed here highlight the importance of the birth site as the location where the mutual bonding between the mother and her young takes place. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

FIELD NOTES ON VERTEBRATES COLLECTED BY THE SMITHSONIAN - CHRYSLER EAST AFRICAN EXPEDI- TION OF 1926 By Arthur Loveridge, Of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, Mass. In 1926 an expedition to secure live animals for the United States National Zoological Park at Washington was made possible through the generosity of Mr. Walter Chrysler. Dr. W. M. Mann, the director of the Zoological Park, has already published a report on the trip; ^ the following observations were made by the present writer, who was in charge of the base camp at Dodoma during three and a half of the four months that the expedition was in the field. The personnel of the party consisted of Dr. W. M. Mann, leader of the expedition; F. G. Carnochan, zoologist; Stephen Haweis, artist; Charles Charlton, photographer; and the writer. Several local hunters assisted the party in the field for longer or shorter periods, and Mr. Le Mesurier operated the Chrysler car. The expedition landed at Dar es Salaam, capital and chief port of entry for Tanganyika Territory (late German East Africa), on Thursday, May 6, and left on the following Monday by train for Dodoma, which had been selected as headquarters. The expedition sailed from Dar es Salaam on September 9. Dodoma is situated on the Central Railway almost exactly one- third of the distance between the coast and Lake Tanganyika. It was primarily selected as being a tsetse-free area and therefore a cattle country where milk in abundance could be obtained for the young animals; it is also the center of a region unusually free from stock diseases. -

Udder Morphology, Milk Production and Udder Health in Small Ruminants

J. Vrdoljak et al.: Udder morphology, milk production and udder health in small ruminants, et al.: Udder morphology, J. Vrdoljak REVIEW | UDK: 636.37 | DoI: 10.15567/mljekarstvo.2020.0201 REcEIVED: 17.10.2019. | AccEptED: 20.03.2020. Udder morphology, milk production and udder health in small ruminants Josip Vrdoljak1, Zvonimir Prpić 2*, Dubravka Samaržija 3, Ivan Vnučec 2, Miljenko Konjačić 2, Nikolina Kelava Ugarković 2 1Pleter usluge d.o.o., Čerinina 23, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 2University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Animal Science and Technology, Svetošimunska cesta 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 3University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Dairy Science, Svetošimunska cesta 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Mljekarstvo In recent years there has been an increasing trend in research of sheep and goat udder morphology, not only from the view of its suitability for machine milking, but also in terms of milk yield and mam- 70 (2), 75-84 (2020) mary gland health. More precisely, herds consisting of high-yielding sheep and goats as a result of long-term and one-sided selection to increase milk yield, have been characterised by distortion of the udder morphology caused by increasing the pressure of udder weight on its suspensory system. Along with the deteriorated milking traits, which is negatively reflected on the udder health, some udder mor- phology traits are often emphasized as factor of production longevity of dairy sheep and goats. Since the intention of farmers and breeders nowadays is to increase the milk yield of sheep and goats while maintaining desirable udder morphology and udder health, the aim of this paper is to give a detailed overview of the current knowledge about the relationship of morphological udder traits with milk yield, and the health of the mammary gland of sheep and goats. -

The Structure of the Cow's Udder

UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION BULLETIN 344 The Structure of the Cow's Udder C. W. T u RN ER COLUMBIA, MISSOURI JANUARY, 1935 UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE Agricultural Experiment Station EXECUTIVE BOARD OF CURATORS.-MERCER ARNOLD, joplin; H. J. BLANTON. Pario: GEORGE C. WILLSON, St. Louio STATION STAFF, JANUARY, 1935 WALTER WILLIAMS, L.L. D., President FREDERICK A. MIDDLEBUSH, Ph. D ., Acting President F B . MUMFORD, M S~ D. Agr., Director S. B. SHIRKY, A.M., Asst. to Director MISS ELLA PAHMEIER, Secretary AGRICULTURAL CHEMISTRY E. MARION BROWN, A.M.* A. G. HoGAN, Ph.D. Mtss CLARA FuHR, M.S.* L. D. HAIGH, Ph.D. E. W. CowAN, A.M. HOME ECONOMICS J.UTHitP. R. RICHARDSON, Ph.D. U. S. AsHwOJ.TH. Ph.D MABEL CAMPBELL, A.M. A.M. ]ESSIE ALICE CLINE, A.M. S. R. JoHNSON, ADELLA EPPEL GINTER, M.S. HELEN BERESFORD, B.S. AGRICULTtlRAL ECONOMICS BERTHA BtSBI!Y, Ph.D. 0. R. JoHNsoN, A.M ]ESSIE v. COLES, Ph.D. BEN H. FRA>lE, A.M. BERTHA K. WHIPPLE, M.S F. L. THOl<SEN, Ph.D c. H. HAl<llAil, Ph.D. HORTICULTURE AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING T. J. TALBI!kT, A.M. J. C. WooLEY, M .S. A. E. MuRNEEJ<, Ph.D. MAcJ: M. JoNES. M.S. H. G. SwARTWOUT, A.M. G. W. GILES, B.S. in A. E. GEO. CARL VINSON, Ph.D. FRAN!t Holi.SFALL, ]R., A.M. ANIMAL HUSBANDRY R. A. ScRilOEDER, 11.S. in Agr. GEOilGI! E. SMITH, B S. in Agr. E. -

Gross Anatomy and Ultrasonography of the Udder in Goat

Original article http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/jms.105316 Gross anatomy and ultrasonography of the udder in goat ADAM, Z. E. A. S.1, RAGAB, G. A. N.2, AWAAD, A. S.1, TAWFIEK, M. G.1 and MAKSOUD, M. K. M. A.1* 1Anatomy and Embryology Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Beni-Suef University, Beni-Suef 62511, Egypt 2Surgery, Anesthesiology, and Radiology Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Beni-Suef University, Beni-Suef 62511, Egypt *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: The udder is a very important structural and physiological component in all dairy animals, so the precise knowledge of its normal gross morphology is fundamental for the clinical examination. Objective: The current study aimed to clarify the gross anatomical characteristics and ultrasonographic findings of the udder in Egyptian native breeds of goat (Baladi goat). Materials and Methods: Thirteen healthy Baladi goats during lactation period were grossly investigated and then they were examined through B-mode ultrasonography. Two specimens were used for corrosion casting and the remaining specimens were subjected to the anatomical dissection. Results: The gross anatomical investigation revealed that the udder of goat was consisted of two halves; each one had mammary body and teat, and it was suspended in the ventral abdominal wall and pelvic floor through the medial and lateral suspensory laminae. Moreover, each half was composed of a single mammary unit which included the mammary glandular parenchyma, lactiferous ducts, lactiferous sinus and teat canal ended by a teat orifice. These mammary structures showed variant echogenicity during ultrasonographic examination according to their reflective intensity to the ultrasound. -

Internet Research Cheetahs Page of 1

Internet Research Cheetahs CHEETAHS http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/cheetah/ The cheetah is the world's fastest land mammal. With acceleration that would leave most automobiles in the dust, a cheetah can go from 0 to 60 miles (96 kilometers) an hour in only three seconds. These big cats are quite nimble at high speed and can make quick and sudden turns in pursuit of prey. Before unleashing their speed, cheetahs use exceptionally keen eyesight to scan their grassland environment for signs of prey—especially antelope and hares. This big cat is a daylight hunter that benefits from stealthy movement and a distinctive spotted coat that allows it to blend easily into high, dry grasses. When the moment is right a cheetah will sprint after its quarry and attempt to knock it down. Such chases cost the hunter a tremendous amount of energy and are usually over in less than a minute. If successful, the cheetah will often drag its kill to a shady hiding place to protect it from opportunistic animals that sometimes steal a kill before the cheetah can eat. Cheetahs need only drink once every three to four days. Female cheetahs typically have a litter of three cubs and live with them for one and a half to two years. Young cubs spend their first year learning from their mother and practicing hunting techniques with playful games. Male cheetahs live alone or in small groups, often with their littermates. Most wild cheetahs are found in eastern and southwestern Africa. Perhaps only 7,000 to 10,000 of these big cats remain, and those are under pressure as the wide-open grasslands they favor are disappearing at the hands of human settlers. -

Mastitis Control Programs Bovine Mastitis and Milking Management J

AS1129 (Revised) Mastitis Control Programs Bovine Mastitis and Milking Management J. W. Schroeder, Extension Dairy Specialist astitis complex; no simple solutions are Mavailable for its control. Some aspects are well- understood and documented in the scientific literature. Others are controversial, and opinions often are presented as facts. The information and interpretations presented here represent the best judgments accepted by the National Mastitis Council. To simplify understanding of mastitis, you’ll need to consider that three major factors are involved in this Figure 1 disease: the microorganisms that cause it, the cow as host and the environment, which Cows contract udder infection to reduce this exposure and can influence the cow and the at different ages and stages of enhance resistance to udder microorganisms. (Figure 1) the lactation cycle. Cows also disease. More than 100 different vary in their ability to overcome Practical measures are microorganisms can cause an infection once it has been available to maintain common mastitis, and these vary greatly established. Therefore, the forms of mastitis at relatively in the route by which they reach cow plays an active role in the low and acceptable levels in the cow and the nature of the development of mastitis. the majority of herds. While disease they cause. The cows’ environment continued research is needed to influences the numbers and control the less common forms types of bacteria they are of intramammary infection, exposed to and their ability to herd problems are often the resist these microorganisms. result of failure to apply the However, through appropriate proven mastitis-control practices management practices, the consistently and to consider all North Dakota State University environment can be controlled aspects of the disease problem. -

Pathogenesis of Bovine Alphaherpesvirus 2 in Calves Following Different Routes of Inoculation1 Bruna P

Pesq. Vet. Bras. 40(5):360-367, May 2020 DOI: 10.1590/1678-5150-PVB-6588 Original Article Livestock Diseases ISSN 0100-736X (Print) ISSN 1678-5150 (Online) PVB-6588 LD Pathogenesis of Bovine alphaherpesvirus 2 in calves following different routes of inoculation1 Bruna P. Amaral2,3, José C. Jardim4 , Juliana F. Cargnelutti3,5, Mathias Martins6,7 , Rudi Weiblen2,3 and Eduardo F. Flores2,3* ABSTRACT.-Amaral B.P., Jardim J.C., Cargnelutti J.F., Martins M., Weiblen R. & Flores E.F. 2020. Pathogenesis of Bovine alphaherpesvirus 2 in calves inoculated by different routes. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira 40(5):360-367. Setor de Virologia, Departamento de Medicina Veterinária Preventiva, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Av. Roraima 1000, Rua Z, Prédio 63A, Santa Maria, RS 97105-900, Brazil. E-mail: Título Original Bovine alphaherpesvirus 2 (BoHV-2) is the agent of herpetic mammilitis (BHM), a cutaneous and self-limiting disease affecting the udder [email protected] teats of cows. The pathogenesis of BoHV-2 is pourly understood, hampering the development of therapeutic drugs, vaccines [Título traduzido]. and other control measures. This study investigated the pathogenesis of BoHV-2 in calves after inoculation through different routes. Three- to four-months seronegative calves were 7 -1 inoculated with BoHV-2 (10 TCID50.mL ) intramuscular (IM, n=4), intravenous (IV, n=4) Autores and serological monitoring. Calves inoculated by the IV route presented as light increase orin bodytransdermal temperature (TD) afterbetween mild days scarification 6 to 9 post-inoculation (n=4) and submitted (pi). Virus to virological, inoculation clinical by the by hyperemia, small vesicles, mild exudation and scab formation, between days 2 and 8pi. -

The Genetics^ Physiology^ and Economic Importance of the Multinipple Trait in Sheep'

Technical Bulletin No, 909 • December 1945 lBiiÍli||||||Í||l^^^ The Genetics^ Physiology^ and Economic Importance of the Multinipple Trait in Sheep' BY RALPH W. PHTT.TJPS, sciiior (tnimal hu shan dm an, IVALPH (J. SCHOTT, animal huHhaiidmitn, and DAMON A. SPEXCEü, sonor (tninial husbandman. Animal Husbaíidrí/ Dirisicm, llurrau of Animal Industry, A(/ricultural Research Administration. CONTENTS Page Page Introduction 1 Data and discussion—Cont'd Purpose of the study 2 Relation of number of nipples History of the niultinippled sheep . 2 to lamb production 7 Data and discussion 5 Udder capacity and anatomy . Í) Inheritance of the multinipple Sunmiai-y i\m\ conclusions 15 trait 5 Literatui-e cited IG Relation of total number of nipples to number of func- tional nipples 7 INTRODUCTION Ewes having more than two nipples are ol)seryed frequently, but little attention has been given to the nniltinipple trait in sheep- breeding operations or research. Work initiated by Alexander (xraham Bell focused attention on the trait, and the nock founded by him received considerable publicity. His objective was to develop a type of sheep that could produce two or more lambs at a birth and have adequate milk on which to raise them. Investigations with his original flock demonstrated that the number of nipples could be increased by selection, and some success apparently attended efforts to increase the tendency for multiple births. Castle (5)^ examined the data accumulated by Bell (/) and con- cluded that the character, supernumerary nipples, is strongly inherited, ^ Received for publication September 39, 1945. - Ualic mimbers in i)arentheses refer to Liteialnre Cited, p.