Making Every Mating Count June 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheep Newz #14 Autumn 2019

Sheep NewZ #14 Autumn 2019 Hello Members, ASSOCIATION NEWS & VIEWS Thanks to all who have supported this issue of “Sheep NewZ”. It would be good to have some more photos/articles From The President each time other than those on the feature breed. I wonder how much money is being spent on bureaucracy in Hope everyone has had a great time over the the wool research, development and promotion sectors? holiday season. The weather was great here There seem to be several companies with great mission in the south over the summer and everyone statements but is anything much actually happening out seemed to be having lots of fun. there? NZ Merino seems to be achieving the most in both Lambs and ewes are bringing record prices this season advertising their product and developing new uses. which is very pleasing. However the same old fiddle plays Some of the Companies and their mission statements are: - the same old tune to try and bring prices down such as the Wool Research Organisation of New Zealand, “To uncertainty of the Brexit deal, Trump, and the Chinese promote, encourage and fund scientific or industry research economy which shows how we can be exposed so quickly. and information transfer that relates to the post harvest wool Hopefully common sense will prevail and our prices stay up industry” Several projects on going from 2013 – results?? at a reasonable level. Wool Industry Research Ltd – a subsidiary of the above “Focus on investment in research which increases the value It is really disappointing to see our farm training institutes and competiveness of commercial NZ wool based activity facing difficult times. -

Kirkbys Stud Remedy

Article by Lindsay Ferguson Impact Sire KIRKBYS STUD REMEDY - IS HSH ASH Reg: 105194 In KIRKBYS STUD REMEDY - IS HSH we see the outcome of many generations of planned breeding by serious and successful breeders. hose breeders include people associated with great horses - Les KIRKBYS STUD REMEDY - IS HSH T Jensen, Theo Hill, John Stanton, Peter Knight, Alf Bignell and Phillip Colour: Brown Kirkby. In the pedigree of KIRKBYS STUD Height: 15.1hh REMEDY - IS HSH we see Impact Horses Lifespan:PROFILE: 24yrs approxJOHNSTONS (1987 - 2011) DARK SECRET - FS HSH as sire and dam, Impact or Foundation Breeder:Colour Phillip Kirkby, Narrabri,Brown NSW Horses as grandparents, and no less than Narrabri, NSW Performance: All round performance horse four Foundation Horses out of the eight Height 15.1 hh great-grandparents. A solid pedigree indeed Progeny:Lifespan 350 - most notable20 being years (1955mare –VET 1975) SCHOOL TONIC - HSH, gelding YALLATUP BACARDI and stallions – but let’s look at the horse himself. Breeder Unknown KIRKBYS STUD REMEDY - IS HSH YALLATUP REGAL REMEDY - HSH and BOONDEROO BLACKWOOD - HSH. Performance Lightly campdrafted was bred by Phillip Kirkby of Narrabri, New South Wales. He was an excellent 38 registered progeny, the mostdimray notable 02 being the mares CHEX,REALITY VICKIS FLIGHT - FS andHSH the stallion STARLIGHT STUD ANCHOR saddle horse with a docile, unflappable WARRENBRI glamor 02 temperament. He was born in 1987 and Progeny - HSH. Sire ROMEO - IS HSH died in 2011. In that time he travelled a lot, WARRENBRI JULIE lord coronation 02 made many friends, won a bunch of big + plus 3 generation pedigree- IM HSH to be included. -

Nova Scotia Veterinary Medical Association Council

G^r? NOVA SCOTIAVETERINARY MEDICAL ASSOCIATION Registrar's Office 15 Cobequid Road, Lower Sackvllle, NS B4C 2M9 Phone: (902) 865-1876 Fax: (902) 865-2001 E-mail: [email protected] September 24, 2018 Dear Chair, and committee members, My name is Dr Melissa Burgoyne. I am a small animal veterinarian and clinic owner in Lower Sackville, Nova Scotia. I am currently serving my 6th year as a member of the NSVMA Council and currently, I am the past president on the Nova Scotia Veterinary Medical Association Council. I am writing today to express our support of Bill 27 and what it represents to support and advocate for those that cannot do so for themselves. As veterinarians, we all went into veterinary medicine because we want to.help animals, prevent and alleviate suffering. We want to reassure the public that veterinarians are humane professionals who are committed to doing what is best for animals, rather than being motivated by financial reasons. We have Dr. Martell-Moran's paper (see attached) related to declawing, which shows that there are significant and negative effects on behavior, as well as chronic pain. His conclusions indicate that feline declaw which is the removal of the distal phalanx, not just the nail, is associated with a significant increase in the odds of adverse behaviors such as biting, aggression, inappropriate elimination and back pain. The CVMA, AAFP, AVMA and Cat Healthy all oppose this procedure. The Cat Fancier's Association decried it 6 years ago. Asfor the other medically unnecessary cosmetic surgeries, I offer the following based on the Mills article. -

Tail Docking in Dogs: Historical Precedence and Modern Views by Jill Kessler Copyright 2012

Tail Docking in Dogs: Historical Precedence and Modern Views By Jill Kessler Copyright 2012 As everyone gathered in the kitchen to prepare for an extended family dinner, Mother took a large ham and cut off a big piece of the end and put it in another smaller pan to cook. As she prepared the two baking dishes, one of the grandchildren asked, “Grandma, why do you cut off part of the ham?” “Well, thatʼs the way I learned how to do it from my Mom, your great grandmother.” One of the Aunts says, “I thought it was because Dad liked to have his own separate piece.” An Uncle says “I thought it was because it made the meat more tender.” A different Aunt chimes in, “Mom said it was just the way it was always done.” Curious, they decide to ask Great Grandmother the reason why the end of the ham was separated. ************************************* History and Veterinary Standing Tail docking (amputation of the tail) has been done on dogs for hundreds of years. A variety of justifications have been offered, usually in accordance to the historical tasks of the breed. For instance, in hunting dogs, conventional wisdom said it was to prevent injury in the field from nettles, burrs or sticks; in herding or bull-baiting dogs it was thought to help avoid injury from large livestock. In truth, there are two primary historical reasons for docking. For our mastiff-based working dogs that accompanied the ancient Romans, it was believed that tail docking and tongue clipping would ward off rabies.i Obviously, this was before modern bacteriology and vaccines, when rabies was still a feared, lethal zoonotic disease that raced through cities and countrysides, infecting all mammals encountered in its path. -

Romney Sheep Breeders Society Winter Newsletter 2017

NEWSLETTER Issue 1 Romney Sheep Breeders Society Winter Newsletter 2017 MERRY CHRISTMAS - PHOTO BY JULIE MURRAY IN THIS ISSUE Dinner and flock competition report -Ashford cattle show results- Young Romney Breeders- New members welcome -shopping with Romney wools- Sponsorship- merchandise - Winter lamb recipe- council meeting dates Issue Date Dinner at The George and fflocks were so good but had to Youngs Trophy for the most Flock competition results fcome to the following conclusion done for the society Alex Long Small pedigree flock A gathering of the Romney st 1 Larry Cooke Champion Flock breeders enjoyed an evening nd meal of Lamb with family and 2 Mr & Mrs Rawlinson PH&PE Skinner 3rd Cobtree YFC friends Raffle - Generous gifts from Large pedigree Flock Fine dining and conversation were many supporters and 1st PH&PE Skinner only interluded by a humorous talk sponsors gave dinners a 2nd Claire Langrish by President Howard Bates on his chance to dig deep into 3rd Paul Bolden exploits in the Navy and sheep ttheir pockets and manage Commercial Flock industry, presentation of the Flock tto raise an amazing £460 1st Larry Cooke Competition trophies and the Ram nd Thank you to all who took part 2 L Ramsden sale prize winners and your generosity. Judge Alan Barr reported that it 3rd A Dunlop had been a difficult task as all NEWSLETTER | Issue 1 2 Ashford cattle Show -Romney Carcass classes judged by Nick Results Brown There was an amazing entry this year from the Romney Class 42 Best Romney lambs born Breeders in carcases, wool in 2017 and finished lambs. -

Lamb Rearing Performance in Highly Fecund Sheep

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Lamb Rearing Performance in Highly Fecund Sheep J ulie Marie Everett-Hincks 2004 This thesis is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand The Massey University Animal Ethics Committee has approved the studies involving animal manipulations I have prepared this thesis and it is a record of my own work. I took the photos of the sheep, unless otherwise specified. Abstract This thesis investigates ewe and lamb behaviour, genetics and environmental effects to determine whether lamb rearing petformancecan be improved in highly fecund heep. The studies were carried out under commercial pastoral farming conditions. High performing sheep farmers were surveyed to identify management and performance practices that differentiate farms with high and low lamb rearing ucces . Farmers agreed that mothering ability was the most important factor affecting lamb urvival and considered lamb survival to be the most important trait affecting fann profit. The survey identified the Coopwotth breed as the predominant breed of high lambing percentage flocks. Heritability estimates were derived for lamb survival (h2= 0. 1 6), ewe maternal behaviour score (h2= 0.05) and litter survival (h2= 0.00) in a Coopworth flock that had been selected fo r improved maternal ability fo r nearly 30 year . Maternal genetic variation in the Coopworth flock was low fo r lamb and maternal traits and suggests that farmers must con ider the environment and management technique to improve lamb survival. -

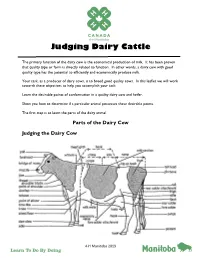

Judging Dairy Cattle

Judging Dairy Cattle The primary function of the dairy cow is the economical production of milk. It has been proven that quality type or form is directly related to function. In other words, a dairy cow with good quality type has the potential to efficiently and economically produce milk. Your task, as a producer of dairy cows, is to breed good quality cows. In this leaflet we will work towards these objectives to help you accomplish your task. Learn the desirable points of conformation in a quality dairy cow and heifer. Show you how to determine if a particular animal possesses these desirable points. The first step is to learn the parts of the dairy animal. Parts of the Dairy Cow Judging the Dairy Cow 4-H Manitoba 2019 Once you know the parts of the body, the next step to becoming a successful dairy judge is to learn what the ideal animal looks like. In this section, we will work through the parts of a dairy cow and learn the desirable and undesirable characteristics. Holstein Canada has developed a scorecard which places relative emphasis on the six areas of importance in the dairy cow. This scorecard is used by all dairy breeds in Canada. The Holstein Cow Scorecard uses these six areas: 1. Frame / Capacity 2. Rump 3. Feet and Legs 4. Mammary System 5. Dairy Character When you judge, do not assign numerical scores. Use the card for relative emphasis only. When cows are classified by the official breed classifiers, classifications and absolute scores are assigned. 2 HOLSTEIN COW SCORE CARD 18 1. -

2021 Breed Show Schedule

49th Annual Breed Show th th 12 – 14 August 2021 Venue – Onley Ground Equestrian Complex, Rugby Entries close Saturday 26th June 2021 Entries to: Scanned / Email: [email protected] Post: Mrs Hazel Thompson Culworth Station Banbury Road Moreton Pinkney Northamptonshire NN11 3SQ 1 Guide to the schedule: Page No Content 3 Notes & General Information 4 Advice & Guidelines 5 Advice & Guidelines contd 6 Rules of the Show 7 Dressage and Riding Club Test 8 Ridden Showing 9 In Hand 10 Show Jumping & Style & Performance 11 Combined Training and Activity & Fun Classes 12 Best Turned Out & Veteran 13 Driving 14 Clifton Activity, Team Challenge, Golden Oldie, Childrens Performance 15 Championships 16 Show Timetable Entry Fees Entry fee for each class £13.00 * Stable Deposit per stable £10.00 (refunded on departure providing stable is left clean & tidy) * the following classes will have a reduced entry fee of £10.00 Prettiest Mare, Handsomest Gelding, Junior Rider, Junior Handler, Horse & Hound, Fancy Dress * Combined training, enter qualifying classes and just pay individual class fees (no extra) LATE ENTRIES ALL entries received after Friday 26th June 2021 will only be accepted at the discretion of the society. IMPORTANT NOTICE - ALL FEES We are not accepting cheques or cash by way of payment this year. Entries must be paid for via Bank Transfer Bank details: Sort Code 54-21-50 Account number 30026385 Please quote your surname in the reference IMPORTANT NOTICE – STABLE HOURS Entry to the stables will be restricted (except in the case of emergency) to between the hours of 06:00 and 22:00. -

From Birth to Colostrum: Early Steps Leading to Lamb Survival Raymond Nowak, Pascal Poindron

From birth to colostrum: early steps leading to lamb survival Raymond Nowak, Pascal Poindron To cite this version: Raymond Nowak, Pascal Poindron. From birth to colostrum: early steps leading to lamb survival. Reproduction Nutrition Development, EDP Sciences, 2006, 46 (4), pp.431-446. 10.1051/rnd:2006023. hal-00900627 HAL Id: hal-00900627 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00900627 Submitted on 1 Jan 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 46 (2006) 431–446 431 c INRA, EDP Sciences, 2006 DOI: 10.1051/rnd:2006023 Review From birth to colostrum: early steps leading to lamb survival Raymond N*, Pascal P Laboratoire de Comportements, Neurobiologie et Adaptation, UMR 6175 CNRS-INRA-Université François Rabelais-Haras Nationaux, Unité de Physiologie de la Reproduction et des Comportements, INRA, 37380 Nouzilly, France Abstract – New-born lambs have limited energy reserves and need a rapid access to colostrum to maintain homeothermy and survive. In addition to energy, colostrum provides immunoglobulins which ensure passive systemic immunity. Therefore, getting early access to the udder is essential for the neonate. The results from the literature reviewed here highlight the importance of the birth site as the location where the mutual bonding between the mother and her young takes place. -

Udder Morphology, Milk Production and Udder Health in Small Ruminants

J. Vrdoljak et al.: Udder morphology, milk production and udder health in small ruminants, et al.: Udder morphology, J. Vrdoljak REVIEW | UDK: 636.37 | DoI: 10.15567/mljekarstvo.2020.0201 REcEIVED: 17.10.2019. | AccEptED: 20.03.2020. Udder morphology, milk production and udder health in small ruminants Josip Vrdoljak1, Zvonimir Prpić 2*, Dubravka Samaržija 3, Ivan Vnučec 2, Miljenko Konjačić 2, Nikolina Kelava Ugarković 2 1Pleter usluge d.o.o., Čerinina 23, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 2University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Animal Science and Technology, Svetošimunska cesta 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 3University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Dairy Science, Svetošimunska cesta 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Mljekarstvo In recent years there has been an increasing trend in research of sheep and goat udder morphology, not only from the view of its suitability for machine milking, but also in terms of milk yield and mam- 70 (2), 75-84 (2020) mary gland health. More precisely, herds consisting of high-yielding sheep and goats as a result of long-term and one-sided selection to increase milk yield, have been characterised by distortion of the udder morphology caused by increasing the pressure of udder weight on its suspensory system. Along with the deteriorated milking traits, which is negatively reflected on the udder health, some udder mor- phology traits are often emphasized as factor of production longevity of dairy sheep and goats. Since the intention of farmers and breeders nowadays is to increase the milk yield of sheep and goats while maintaining desirable udder morphology and udder health, the aim of this paper is to give a detailed overview of the current knowledge about the relationship of morphological udder traits with milk yield, and the health of the mammary gland of sheep and goats. -

The Structure of the Cow's Udder

UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION BULLETIN 344 The Structure of the Cow's Udder C. W. T u RN ER COLUMBIA, MISSOURI JANUARY, 1935 UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE Agricultural Experiment Station EXECUTIVE BOARD OF CURATORS.-MERCER ARNOLD, joplin; H. J. BLANTON. Pario: GEORGE C. WILLSON, St. Louio STATION STAFF, JANUARY, 1935 WALTER WILLIAMS, L.L. D., President FREDERICK A. MIDDLEBUSH, Ph. D ., Acting President F B . MUMFORD, M S~ D. Agr., Director S. B. SHIRKY, A.M., Asst. to Director MISS ELLA PAHMEIER, Secretary AGRICULTURAL CHEMISTRY E. MARION BROWN, A.M.* A. G. HoGAN, Ph.D. Mtss CLARA FuHR, M.S.* L. D. HAIGH, Ph.D. E. W. CowAN, A.M. HOME ECONOMICS J.UTHitP. R. RICHARDSON, Ph.D. U. S. AsHwOJ.TH. Ph.D MABEL CAMPBELL, A.M. A.M. ]ESSIE ALICE CLINE, A.M. S. R. JoHNSON, ADELLA EPPEL GINTER, M.S. HELEN BERESFORD, B.S. AGRICULTtlRAL ECONOMICS BERTHA BtSBI!Y, Ph.D. 0. R. JoHNsoN, A.M ]ESSIE v. COLES, Ph.D. BEN H. FRA>lE, A.M. BERTHA K. WHIPPLE, M.S F. L. THOl<SEN, Ph.D c. H. HAl<llAil, Ph.D. HORTICULTURE AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING T. J. TALBI!kT, A.M. J. C. WooLEY, M .S. A. E. MuRNEEJ<, Ph.D. MAcJ: M. JoNES. M.S. H. G. SwARTWOUT, A.M. G. W. GILES, B.S. in A. E. GEO. CARL VINSON, Ph.D. FRAN!t Holi.SFALL, ]R., A.M. ANIMAL HUSBANDRY R. A. ScRilOEDER, 11.S. in Agr. GEOilGI! E. SMITH, B S. in Agr. E. -

UZB Tiroler Haflinger

Policies pertaining to the studbook of origin for the “Haflinger” breed 1. General information about the breeders’ organization Haflinger Horse-Breeders’ Association of Tyrol Schlossallee 31, 6341 Ebbs Austria 2. Policies 2.1. Records of Descent 2.1.1 Number of Preceding Generations At least 4 generations of the Haflinger breed, both maternal and paternal, must be recorded in the studbook 2.1.2. Information about the breeding animal and its ancestry a) Name, breed, I.D. number or other form of identification b) Date and place of birth, gender c) Breeder d) Section of the studbook e) Parentage f) Additional ancestry information: - Name and address of the Haflinger-certified breeding organization. - Description of external and internal traits respective to criteria stipulated in corresponding subsections of the main section. - For stallions, blood lines indicated by means of the letter A, B, M, N, S, St or W. 2.2. Breed Characteristics 2.2.1. General Description and Use Haflinger are expressive, versatile riding horses. They are noble natured with a good character and can be used for any kind of riding and driving by children and adults. They may also be used as draught horses. Genealogically, 7 bloodlines are distinguished: A, B, M, N, S, St and W. Seite 1 von 8 2.2.2. External Appearance Color and Markings; Basic coloration – all shades of chestnut, from pale chestnut to dark liver, are possible. The color should be full and pure, trace or black spots etc. are not desirable. Head markings are acceptable, leg markings are not desirable. Light or white mane and tail are desired, slightly reddish ones are tolerated; red, salt-and-pepper and grey are undesirable.