From Birth to Colostrum: Early Steps Leading to Lamb Survival Raymond Nowak, Pascal Poindron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 'Wild' Sheep of Britain

The 'Wild' Sheep of Britain </. C. Greig and A. B. Cooper Primitive breeds of sheep and goats, such as the Ronaldsay sheep of Orkney, could be in danger of disappearing with the present rapid decline in pastoral farming. The authors, both members of the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources in Edinburgh University, point out that, quite apart from their historical and cultural interest, these breeds have an important part to play in modern livestock breeding, which needs a constant infusion of new genes from unimproved breeds to get the benefits of hybrid vigour. Moreover these primitive breeds are able to use the poor land and live in the harsh environment which no modern hybrid sheep can stand. Recent work on primitive breeds of sheep and goats in Scotland has drawn attention not only to the necessity for conserving them, but also to the fact that there is no organisation taking a direct scientific in- terest in them. Primitive livestock strains are the jetsam of the Agricul- tural Revolution, and they tend to survive in Europe's peripheral regions. The sheep breeds are the best examples, such as the sheep of Ushant, off the Brittany coast, the Ronaldsay sheep of Orkney, the Shetland sheep, the Soay sheep of St Kilda, and the Manx Loaghtan breed. Presumably all have survived because of their isolation in these remote and usually infertile areas. A 'primitive breed' is a livestock breed which has remained relatively unchanged through the last 200 years of modern animal-breeding techniques. The word 'primitive' is perhaps unfortunate, since it implies qualities which are obsolete or undeveloped. -

Sheep Newz #14 Autumn 2019

Sheep NewZ #14 Autumn 2019 Hello Members, ASSOCIATION NEWS & VIEWS Thanks to all who have supported this issue of “Sheep NewZ”. It would be good to have some more photos/articles From The President each time other than those on the feature breed. I wonder how much money is being spent on bureaucracy in Hope everyone has had a great time over the the wool research, development and promotion sectors? holiday season. The weather was great here There seem to be several companies with great mission in the south over the summer and everyone statements but is anything much actually happening out seemed to be having lots of fun. there? NZ Merino seems to be achieving the most in both Lambs and ewes are bringing record prices this season advertising their product and developing new uses. which is very pleasing. However the same old fiddle plays Some of the Companies and their mission statements are: - the same old tune to try and bring prices down such as the Wool Research Organisation of New Zealand, “To uncertainty of the Brexit deal, Trump, and the Chinese promote, encourage and fund scientific or industry research economy which shows how we can be exposed so quickly. and information transfer that relates to the post harvest wool Hopefully common sense will prevail and our prices stay up industry” Several projects on going from 2013 – results?? at a reasonable level. Wool Industry Research Ltd – a subsidiary of the above “Focus on investment in research which increases the value It is really disappointing to see our farm training institutes and competiveness of commercial NZ wool based activity facing difficult times. -

St.Kilda Soay Sheep & Mouse Projects

ST. KILDA SOAY SHEEP & MOUSE PROJECTS: ANNUAL REPORT 2009 J.G. Pilkington 1, S.D. Albon 2, A. Bento 4, D. Beraldi 1, T. Black 1, E. Brown 6, D. Childs 6, T.H. Clutton-Brock 3, T. Coulson 4, M.J. Crawley 4, T. Ezard 4, P. Feulner 6, A. Graham 10 , J. Gratten 6, A. Hayward 1, S. Johnston 6, P. Korsten 1, L. Kruuk 1, A.F. McRae 9, B. Morgan 7, M. Morrissey 1, S. Morrissey 1, F. Pelletier 4, J.M. Pemberton 1, 6 6 8 9 10 1 M.R. Robinson , J. Slate , I.R. Stevenson , P. M. Visscher , K. Watt , A. Wilson , K. Wilson 5. 1Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh. 2Macaulay Institute, Aberdeen. 3Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge. 4Department of Biological Sciences, Imperial College. 5Department of Biological Sciences, Lancaster University. 6 Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield. 7 Institute of Maths and Statistics, University of Kent at Canterbury. 8Sunadal Data Solutions, Edinburgh. 9Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Australia. 10 Institute of Immunity and Infection research, University of Edinburgh POPULATION OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................................................... 1 REPORTS ON COMPONENT STUDIES .................................................................................................................... 4 Vegetation ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Weather during population -

Annual Report 2019

ST. KILDA SOAY SHEEP PROJECT: ANNUAL REPORT 2019 J.G. Pilkington5,1, C. Bérénos1, X. Bal1, D. Childs2, Y. Corripio-Miyar3, A. Fenton11, M. Fraser8, A. Free12, H. Froy9, A. Hayward3, H. Hipperson2, W. Huang1, D. Hunter2,5, S.E. Johnston1, F. Kenyon3, H. Lemon1, D. McBean3, L. McNally1, T. McNeilly3, R.J. Mellanby4, M. Morrissey5, D. Nussey1, R. J. Pakeman7, A. Pedersen1, J.M. Pemberton1, J. Slate2, A.M. Sparks10, I.R. Stevenson6, M.A. Stoffel1, A. Sweeny1, H. Vallin8, K. Watt1. 1Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh. 2Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield. 3Moredun Research Institute, Edinburgh. 4Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh. 5School of Biology, University of St. Andrews. 6Sunadal Data Solutions, Penicuik. 7James Hutton Institute, Craigiebuckler, Aberdeen. 8Institute of Biological, Environmental & Rural Sciences, Aberystwyth University. 9Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim. 10School of Biology, University of Leeds. 11Institute of Integrative Biology, University of Liverpool. 12Institute of Quantitative Biology, Biochemistry and Biotechnology, University of Edinburgh. POPULATION OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................... 2 REPORTS ON COMPONENT STUDIES ........................................................................................ 4 Determination of Pregnancy in Soay sheep .................................................................................. -

Romney Sheep Breeders Society Winter Newsletter 2017

NEWSLETTER Issue 1 Romney Sheep Breeders Society Winter Newsletter 2017 MERRY CHRISTMAS - PHOTO BY JULIE MURRAY IN THIS ISSUE Dinner and flock competition report -Ashford cattle show results- Young Romney Breeders- New members welcome -shopping with Romney wools- Sponsorship- merchandise - Winter lamb recipe- council meeting dates Issue Date Dinner at The George and fflocks were so good but had to Youngs Trophy for the most Flock competition results fcome to the following conclusion done for the society Alex Long Small pedigree flock A gathering of the Romney st 1 Larry Cooke Champion Flock breeders enjoyed an evening nd meal of Lamb with family and 2 Mr & Mrs Rawlinson PH&PE Skinner 3rd Cobtree YFC friends Raffle - Generous gifts from Large pedigree Flock Fine dining and conversation were many supporters and 1st PH&PE Skinner only interluded by a humorous talk sponsors gave dinners a 2nd Claire Langrish by President Howard Bates on his chance to dig deep into 3rd Paul Bolden exploits in the Navy and sheep ttheir pockets and manage Commercial Flock industry, presentation of the Flock tto raise an amazing £460 1st Larry Cooke Competition trophies and the Ram nd Thank you to all who took part 2 L Ramsden sale prize winners and your generosity. Judge Alan Barr reported that it 3rd A Dunlop had been a difficult task as all NEWSLETTER | Issue 1 2 Ashford cattle Show -Romney Carcass classes judged by Nick Results Brown There was an amazing entry this year from the Romney Class 42 Best Romney lambs born Breeders in carcases, wool in 2017 and finished lambs. -

Lamb Rearing Performance in Highly Fecund Sheep

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Lamb Rearing Performance in Highly Fecund Sheep J ulie Marie Everett-Hincks 2004 This thesis is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand The Massey University Animal Ethics Committee has approved the studies involving animal manipulations I have prepared this thesis and it is a record of my own work. I took the photos of the sheep, unless otherwise specified. Abstract This thesis investigates ewe and lamb behaviour, genetics and environmental effects to determine whether lamb rearing petformancecan be improved in highly fecund heep. The studies were carried out under commercial pastoral farming conditions. High performing sheep farmers were surveyed to identify management and performance practices that differentiate farms with high and low lamb rearing ucces . Farmers agreed that mothering ability was the most important factor affecting lamb urvival and considered lamb survival to be the most important trait affecting fann profit. The survey identified the Coopwotth breed as the predominant breed of high lambing percentage flocks. Heritability estimates were derived for lamb survival (h2= 0. 1 6), ewe maternal behaviour score (h2= 0.05) and litter survival (h2= 0.00) in a Coopworth flock that had been selected fo r improved maternal ability fo r nearly 30 year . Maternal genetic variation in the Coopworth flock was low fo r lamb and maternal traits and suggests that farmers must con ider the environment and management technique to improve lamb survival. -

Judging Dairy Cattle

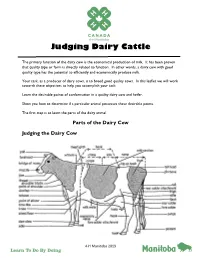

Judging Dairy Cattle The primary function of the dairy cow is the economical production of milk. It has been proven that quality type or form is directly related to function. In other words, a dairy cow with good quality type has the potential to efficiently and economically produce milk. Your task, as a producer of dairy cows, is to breed good quality cows. In this leaflet we will work towards these objectives to help you accomplish your task. Learn the desirable points of conformation in a quality dairy cow and heifer. Show you how to determine if a particular animal possesses these desirable points. The first step is to learn the parts of the dairy animal. Parts of the Dairy Cow Judging the Dairy Cow 4-H Manitoba 2019 Once you know the parts of the body, the next step to becoming a successful dairy judge is to learn what the ideal animal looks like. In this section, we will work through the parts of a dairy cow and learn the desirable and undesirable characteristics. Holstein Canada has developed a scorecard which places relative emphasis on the six areas of importance in the dairy cow. This scorecard is used by all dairy breeds in Canada. The Holstein Cow Scorecard uses these six areas: 1. Frame / Capacity 2. Rump 3. Feet and Legs 4. Mammary System 5. Dairy Character When you judge, do not assign numerical scores. Use the card for relative emphasis only. When cows are classified by the official breed classifiers, classifications and absolute scores are assigned. 2 HOLSTEIN COW SCORE CARD 18 1. -

Flag Fen: a Natural History

Flag Fen: A natural history �������� working today ��������������������������� for nature tomorrow Flag Fen booklet.indd 1 16/3/05 3:23:24 pm Nature and wildlife is all around us. Wherever you go, from the remotest islands to the busiest cities, you will find plants and animals in some of the most unlikely places. A world without wildlife would be quite impossible for us to live on. As all forms of life on Earth follow natural cycles, so we humans depend on our plants and animals for food, clothing, medicines and even building materials. All our fruit, vegetables and meat come originally from a natural source, but in this country we are used to buying these products from supermarkets, carefully prepared and packaged. It’s sometimes hard to imagine that the perfectly-formed apples and carrots we see actually grew in an orchard or field! Imagine how much harder it would be if we had to find food for ourselves. Would you be able to find your next meal, or sufficient food to feed your family? Three thousand years ago, long before supermarkets, the people who lived around Flag Fen had to solve these problems every day. Flag Fen is an internationally important archaeological site, which has provided valuable information about Bronze Age people and their environment. Although they were farmers, wild plants and animals played an important part in the day-to- day survival of those early fen folk. 2 Flag Fen booklet.indd 2 16/3/05 3:23:31 pm Scabious flowers at Flag Fen: this former home to ancient Britons is right next to modern houses and modern life – and wildlife thrives here. -

Survival and Behaviour of Castrated Soay Sheep (Ovis Aries) in a Feral Island Population on Hirta, St

Sulphur0815 J. Zool., Lond. (1997) 243, 623-636 Survival and behaviour of castrated Soay sheep (Ovis aries) in a feral island population on Hirta, St. Kilda, Scotland P. A. JEWELL Department of Zoology, University of Cumbridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EJ (Accepted 19 March 1997) (With 5 figures in the text) The free-living population of Soay sheep on the island of Hirta, St. Kilda, in the Outer Hebrides, has been intensively studied since 1959. The present study was initiated to throw light on the causes of the high mortality rate of adult rams in comparison to that of ewes. In 1978, 1979 and 1980, a total of 72 male lambs was castrated within a day or two of birth. The survival of these castrates has been much longer than that of the entire rams, marked as controls, and longer than that of ewes of the cohorts of the same years. The daily activity pattern of the castrates was similar to that of ewes rather than that of rams. In particular, during the rut the castrates spent most of the daylight hours grazing, in contrast to the rams who were continuously moving and involved in agonistic and sexual encounters. This study substantiates the earlier assertion that the costs in energy of reproduction are a major cause of mortality in temperate zone ungulates. The social organization of some castrates was similar to that of females in that they remained with the home-range group of ewes into which they were born, but other individuals resembled males in that these castrates clubbed together in their own groups. -

Udder Morphology, Milk Production and Udder Health in Small Ruminants

J. Vrdoljak et al.: Udder morphology, milk production and udder health in small ruminants, et al.: Udder morphology, J. Vrdoljak REVIEW | UDK: 636.37 | DoI: 10.15567/mljekarstvo.2020.0201 REcEIVED: 17.10.2019. | AccEptED: 20.03.2020. Udder morphology, milk production and udder health in small ruminants Josip Vrdoljak1, Zvonimir Prpić 2*, Dubravka Samaržija 3, Ivan Vnučec 2, Miljenko Konjačić 2, Nikolina Kelava Ugarković 2 1Pleter usluge d.o.o., Čerinina 23, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 2University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Animal Science and Technology, Svetošimunska cesta 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 3University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Dairy Science, Svetošimunska cesta 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Mljekarstvo In recent years there has been an increasing trend in research of sheep and goat udder morphology, not only from the view of its suitability for machine milking, but also in terms of milk yield and mam- 70 (2), 75-84 (2020) mary gland health. More precisely, herds consisting of high-yielding sheep and goats as a result of long-term and one-sided selection to increase milk yield, have been characterised by distortion of the udder morphology caused by increasing the pressure of udder weight on its suspensory system. Along with the deteriorated milking traits, which is negatively reflected on the udder health, some udder mor- phology traits are often emphasized as factor of production longevity of dairy sheep and goats. Since the intention of farmers and breeders nowadays is to increase the milk yield of sheep and goats while maintaining desirable udder morphology and udder health, the aim of this paper is to give a detailed overview of the current knowledge about the relationship of morphological udder traits with milk yield, and the health of the mammary gland of sheep and goats. -

Sheep & Goat Catalogue

CIRENCESTER MARKET Rare, Native & Traditional Breeds Show & Sale of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats & Poultry SHEEP & GOAT CATALOGUE SATURDAY 1ST AUGUST 2015 SHOW TIMES Cotswold Sheep Show - Friday 31st July 2015 at 5.00 p.m. Gloucester Cattle - Saturday 1st August 2015 at 10.30 a.m Gloucester Old Spots Pigs Show - Saturday 1st August 2015 at 10.30 a.m. SALE TIMES Poultry Sale - 10.00 a.m. Cotswold Sheep - 11.00 a.m. General Sheep - Follows Cotswold Sheep Sale Gloucester Cattle - Approx 12.30 p.m. General Cattle - Follows Gloucester Cattle Sale Gloucester Old Spots Pigs - Approx 1.15 p.m. General Pigs - Follows Gloucester Old Spots Pigs Sale LIVESTOCK SALE CENTRE BIO-SECURITY MEASURES Purchasers are requested to wear clean footwear and clothes when attending the sale. All livestock vehicles should be fully cleaned and disinfected before coming to the Market Site. METHOD OF SALE All Cattle, Sheep, Goats, Pigs, Horses & Poultry will be sold in £’s (pounds) and strictly in catalogue order, unless any alteration is authorised and announced by the Auctioneers. All Poultry will be subject to 10% Buyers Premium. CONDITIONS OF SALE The sale is held subject to the Auctioneer's General terms and Conditions of Sale and to the Auction Conditions of Sale recommended for use at Markets by the Livestock Auctioneers Association. These Conditions will be displayed in full at the Sale Premises. CATALOGUE ENTRIES Whilst every effort has been made to ensure that the descriptions are accurate no guarantee is given or implied. Buyers should note that lots may be withdrawn and other lots added prior to the sale day. -

The Structure of the Cow's Udder

UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION BULLETIN 344 The Structure of the Cow's Udder C. W. T u RN ER COLUMBIA, MISSOURI JANUARY, 1935 UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE Agricultural Experiment Station EXECUTIVE BOARD OF CURATORS.-MERCER ARNOLD, joplin; H. J. BLANTON. Pario: GEORGE C. WILLSON, St. Louio STATION STAFF, JANUARY, 1935 WALTER WILLIAMS, L.L. D., President FREDERICK A. MIDDLEBUSH, Ph. D ., Acting President F B . MUMFORD, M S~ D. Agr., Director S. B. SHIRKY, A.M., Asst. to Director MISS ELLA PAHMEIER, Secretary AGRICULTURAL CHEMISTRY E. MARION BROWN, A.M.* A. G. HoGAN, Ph.D. Mtss CLARA FuHR, M.S.* L. D. HAIGH, Ph.D. E. W. CowAN, A.M. HOME ECONOMICS J.UTHitP. R. RICHARDSON, Ph.D. U. S. AsHwOJ.TH. Ph.D MABEL CAMPBELL, A.M. A.M. ]ESSIE ALICE CLINE, A.M. S. R. JoHNSON, ADELLA EPPEL GINTER, M.S. HELEN BERESFORD, B.S. AGRICULTtlRAL ECONOMICS BERTHA BtSBI!Y, Ph.D. 0. R. JoHNsoN, A.M ]ESSIE v. COLES, Ph.D. BEN H. FRA>lE, A.M. BERTHA K. WHIPPLE, M.S F. L. THOl<SEN, Ph.D c. H. HAl<llAil, Ph.D. HORTICULTURE AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING T. J. TALBI!kT, A.M. J. C. WooLEY, M .S. A. E. MuRNEEJ<, Ph.D. MAcJ: M. JoNES. M.S. H. G. SwARTWOUT, A.M. G. W. GILES, B.S. in A. E. GEO. CARL VINSON, Ph.D. FRAN!t Holi.SFALL, ]R., A.M. ANIMAL HUSBANDRY R. A. ScRilOEDER, 11.S. in Agr. GEOilGI! E. SMITH, B S. in Agr. E.