The Genetics^ Physiology^ and Economic Importance of the Multinipple Trait in Sheep'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

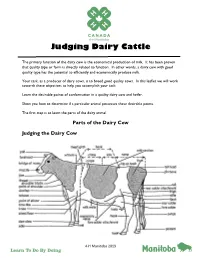

Judging Dairy Cattle

Judging Dairy Cattle The primary function of the dairy cow is the economical production of milk. It has been proven that quality type or form is directly related to function. In other words, a dairy cow with good quality type has the potential to efficiently and economically produce milk. Your task, as a producer of dairy cows, is to breed good quality cows. In this leaflet we will work towards these objectives to help you accomplish your task. Learn the desirable points of conformation in a quality dairy cow and heifer. Show you how to determine if a particular animal possesses these desirable points. The first step is to learn the parts of the dairy animal. Parts of the Dairy Cow Judging the Dairy Cow 4-H Manitoba 2019 Once you know the parts of the body, the next step to becoming a successful dairy judge is to learn what the ideal animal looks like. In this section, we will work through the parts of a dairy cow and learn the desirable and undesirable characteristics. Holstein Canada has developed a scorecard which places relative emphasis on the six areas of importance in the dairy cow. This scorecard is used by all dairy breeds in Canada. The Holstein Cow Scorecard uses these six areas: 1. Frame / Capacity 2. Rump 3. Feet and Legs 4. Mammary System 5. Dairy Character When you judge, do not assign numerical scores. Use the card for relative emphasis only. When cows are classified by the official breed classifiers, classifications and absolute scores are assigned. 2 HOLSTEIN COW SCORE CARD 18 1. -

From Birth to Colostrum: Early Steps Leading to Lamb Survival Raymond Nowak, Pascal Poindron

From birth to colostrum: early steps leading to lamb survival Raymond Nowak, Pascal Poindron To cite this version: Raymond Nowak, Pascal Poindron. From birth to colostrum: early steps leading to lamb survival. Reproduction Nutrition Development, EDP Sciences, 2006, 46 (4), pp.431-446. 10.1051/rnd:2006023. hal-00900627 HAL Id: hal-00900627 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00900627 Submitted on 1 Jan 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 46 (2006) 431–446 431 c INRA, EDP Sciences, 2006 DOI: 10.1051/rnd:2006023 Review From birth to colostrum: early steps leading to lamb survival Raymond N*, Pascal P Laboratoire de Comportements, Neurobiologie et Adaptation, UMR 6175 CNRS-INRA-Université François Rabelais-Haras Nationaux, Unité de Physiologie de la Reproduction et des Comportements, INRA, 37380 Nouzilly, France Abstract – New-born lambs have limited energy reserves and need a rapid access to colostrum to maintain homeothermy and survive. In addition to energy, colostrum provides immunoglobulins which ensure passive systemic immunity. Therefore, getting early access to the udder is essential for the neonate. The results from the literature reviewed here highlight the importance of the birth site as the location where the mutual bonding between the mother and her young takes place. -

Udder Morphology, Milk Production and Udder Health in Small Ruminants

J. Vrdoljak et al.: Udder morphology, milk production and udder health in small ruminants, et al.: Udder morphology, J. Vrdoljak REVIEW | UDK: 636.37 | DoI: 10.15567/mljekarstvo.2020.0201 REcEIVED: 17.10.2019. | AccEptED: 20.03.2020. Udder morphology, milk production and udder health in small ruminants Josip Vrdoljak1, Zvonimir Prpić 2*, Dubravka Samaržija 3, Ivan Vnučec 2, Miljenko Konjačić 2, Nikolina Kelava Ugarković 2 1Pleter usluge d.o.o., Čerinina 23, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 2University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Animal Science and Technology, Svetošimunska cesta 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 3University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Dairy Science, Svetošimunska cesta 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Mljekarstvo In recent years there has been an increasing trend in research of sheep and goat udder morphology, not only from the view of its suitability for machine milking, but also in terms of milk yield and mam- 70 (2), 75-84 (2020) mary gland health. More precisely, herds consisting of high-yielding sheep and goats as a result of long-term and one-sided selection to increase milk yield, have been characterised by distortion of the udder morphology caused by increasing the pressure of udder weight on its suspensory system. Along with the deteriorated milking traits, which is negatively reflected on the udder health, some udder mor- phology traits are often emphasized as factor of production longevity of dairy sheep and goats. Since the intention of farmers and breeders nowadays is to increase the milk yield of sheep and goats while maintaining desirable udder morphology and udder health, the aim of this paper is to give a detailed overview of the current knowledge about the relationship of morphological udder traits with milk yield, and the health of the mammary gland of sheep and goats. -

The Structure of the Cow's Udder

UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION BULLETIN 344 The Structure of the Cow's Udder C. W. T u RN ER COLUMBIA, MISSOURI JANUARY, 1935 UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE Agricultural Experiment Station EXECUTIVE BOARD OF CURATORS.-MERCER ARNOLD, joplin; H. J. BLANTON. Pario: GEORGE C. WILLSON, St. Louio STATION STAFF, JANUARY, 1935 WALTER WILLIAMS, L.L. D., President FREDERICK A. MIDDLEBUSH, Ph. D ., Acting President F B . MUMFORD, M S~ D. Agr., Director S. B. SHIRKY, A.M., Asst. to Director MISS ELLA PAHMEIER, Secretary AGRICULTURAL CHEMISTRY E. MARION BROWN, A.M.* A. G. HoGAN, Ph.D. Mtss CLARA FuHR, M.S.* L. D. HAIGH, Ph.D. E. W. CowAN, A.M. HOME ECONOMICS J.UTHitP. R. RICHARDSON, Ph.D. U. S. AsHwOJ.TH. Ph.D MABEL CAMPBELL, A.M. A.M. ]ESSIE ALICE CLINE, A.M. S. R. JoHNSON, ADELLA EPPEL GINTER, M.S. HELEN BERESFORD, B.S. AGRICULTtlRAL ECONOMICS BERTHA BtSBI!Y, Ph.D. 0. R. JoHNsoN, A.M ]ESSIE v. COLES, Ph.D. BEN H. FRA>lE, A.M. BERTHA K. WHIPPLE, M.S F. L. THOl<SEN, Ph.D c. H. HAl<llAil, Ph.D. HORTICULTURE AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING T. J. TALBI!kT, A.M. J. C. WooLEY, M .S. A. E. MuRNEEJ<, Ph.D. MAcJ: M. JoNES. M.S. H. G. SwARTWOUT, A.M. G. W. GILES, B.S. in A. E. GEO. CARL VINSON, Ph.D. FRAN!t Holi.SFALL, ]R., A.M. ANIMAL HUSBANDRY R. A. ScRilOEDER, 11.S. in Agr. GEOilGI! E. SMITH, B S. in Agr. E. -

Internet Research Cheetahs Page of 1

Internet Research Cheetahs CHEETAHS http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/cheetah/ The cheetah is the world's fastest land mammal. With acceleration that would leave most automobiles in the dust, a cheetah can go from 0 to 60 miles (96 kilometers) an hour in only three seconds. These big cats are quite nimble at high speed and can make quick and sudden turns in pursuit of prey. Before unleashing their speed, cheetahs use exceptionally keen eyesight to scan their grassland environment for signs of prey—especially antelope and hares. This big cat is a daylight hunter that benefits from stealthy movement and a distinctive spotted coat that allows it to blend easily into high, dry grasses. When the moment is right a cheetah will sprint after its quarry and attempt to knock it down. Such chases cost the hunter a tremendous amount of energy and are usually over in less than a minute. If successful, the cheetah will often drag its kill to a shady hiding place to protect it from opportunistic animals that sometimes steal a kill before the cheetah can eat. Cheetahs need only drink once every three to four days. Female cheetahs typically have a litter of three cubs and live with them for one and a half to two years. Young cubs spend their first year learning from their mother and practicing hunting techniques with playful games. Male cheetahs live alone or in small groups, often with their littermates. Most wild cheetahs are found in eastern and southwestern Africa. Perhaps only 7,000 to 10,000 of these big cats remain, and those are under pressure as the wide-open grasslands they favor are disappearing at the hands of human settlers. -

Mastitis Control Programs Bovine Mastitis and Milking Management J

AS1129 (Revised) Mastitis Control Programs Bovine Mastitis and Milking Management J. W. Schroeder, Extension Dairy Specialist astitis complex; no simple solutions are Mavailable for its control. Some aspects are well- understood and documented in the scientific literature. Others are controversial, and opinions often are presented as facts. The information and interpretations presented here represent the best judgments accepted by the National Mastitis Council. To simplify understanding of mastitis, you’ll need to consider that three major factors are involved in this Figure 1 disease: the microorganisms that cause it, the cow as host and the environment, which Cows contract udder infection to reduce this exposure and can influence the cow and the at different ages and stages of enhance resistance to udder microorganisms. (Figure 1) the lactation cycle. Cows also disease. More than 100 different vary in their ability to overcome Practical measures are microorganisms can cause an infection once it has been available to maintain common mastitis, and these vary greatly established. Therefore, the forms of mastitis at relatively in the route by which they reach cow plays an active role in the low and acceptable levels in the cow and the nature of the development of mastitis. the majority of herds. While disease they cause. The cows’ environment continued research is needed to influences the numbers and control the less common forms types of bacteria they are of intramammary infection, exposed to and their ability to herd problems are often the resist these microorganisms. result of failure to apply the However, through appropriate proven mastitis-control practices management practices, the consistently and to consider all North Dakota State University environment can be controlled aspects of the disease problem. -

Pathogenesis of Bovine Alphaherpesvirus 2 in Calves Following Different Routes of Inoculation1 Bruna P

Pesq. Vet. Bras. 40(5):360-367, May 2020 DOI: 10.1590/1678-5150-PVB-6588 Original Article Livestock Diseases ISSN 0100-736X (Print) ISSN 1678-5150 (Online) PVB-6588 LD Pathogenesis of Bovine alphaherpesvirus 2 in calves following different routes of inoculation1 Bruna P. Amaral2,3, José C. Jardim4 , Juliana F. Cargnelutti3,5, Mathias Martins6,7 , Rudi Weiblen2,3 and Eduardo F. Flores2,3* ABSTRACT.-Amaral B.P., Jardim J.C., Cargnelutti J.F., Martins M., Weiblen R. & Flores E.F. 2020. Pathogenesis of Bovine alphaherpesvirus 2 in calves inoculated by different routes. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira 40(5):360-367. Setor de Virologia, Departamento de Medicina Veterinária Preventiva, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Av. Roraima 1000, Rua Z, Prédio 63A, Santa Maria, RS 97105-900, Brazil. E-mail: Título Original Bovine alphaherpesvirus 2 (BoHV-2) is the agent of herpetic mammilitis (BHM), a cutaneous and self-limiting disease affecting the udder [email protected] teats of cows. The pathogenesis of BoHV-2 is pourly understood, hampering the development of therapeutic drugs, vaccines [Título traduzido]. and other control measures. This study investigated the pathogenesis of BoHV-2 in calves after inoculation through different routes. Three- to four-months seronegative calves were 7 -1 inoculated with BoHV-2 (10 TCID50.mL ) intramuscular (IM, n=4), intravenous (IV, n=4) Autores and serological monitoring. Calves inoculated by the IV route presented as light increase orin bodytransdermal temperature (TD) afterbetween mild days scarification 6 to 9 post-inoculation (n=4) and submitted (pi). Virus to virological, inoculation clinical by the by hyperemia, small vesicles, mild exudation and scab formation, between days 2 and 8pi. -

Comparative Evaluation of Udder and Body Conformation Traits of First Lactation ¾ Holstein X ¼ Jersey Versus Holstein Cows# C

Arch Med Vet 47, 85-89 (2015) COMMUNICATION Comparative evaluation of udder and body conformation traits of first lactation ¾ Holstein x ¼ Jersey versus Holstein cows# Comparación de las características de conformación de la ubre y el cuerpo de vacas de primera lactancia ¾ Holstein x ¼ Jersey versus Holstein G Bretschneider*, D Arias, A Cuatrin Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA), Estación Experimental Agropecuaria (EEA)-Rafaela, Santa Fe, Argentina. RESUMEN Con el objetivo de facilitar la selección de razas para cruzamiento se realizó una evaluación comparativa de las características de conformación de vacas cruza ¾ Holstein (HO) x ¼ Jersey (JE) versus vacas HO. Todas las mediciones fueron registradas en vaquillonas de primer parto de 40 a 100 días en lactancia. En relación con la raza HO, para la cruza se registró una menor estatura (-9,62 cm; P = 0,0001), ancho de grupa (–1,55 cm; P = 0,005) y ancho de pecho (–2,18 cm; P = 0,006), más estrechos, profundidad corporal (–6,45 cm; P = 0,04) y perímetro torácico (-10,43 cm; P = 0,0001) menores y menor ángulo de pezuña (–4,61º; P = 0,02). Entre las características de la glándula mamaria, la cruza presentó ubres más profundas (+3,80 cm; P = 0,006) y estrechas (–2,32 cm; P = 0,001), con pezones anteriores más largos (+0,54 cm; P = 0,04) que la raza HO. Se sugiere que ciertos aspectos de la conformación de la glándula mamaria de la cruza ¾ HO x ¼ JE podrían ser factores de riesgo asociados al animal de importancia en el descarte de vacas, principalmente en sistemas lecheros intensificados. -

Making Every Mating Count June 2013

MAKING EVERY MATING COUNT JUNE 2013 0800 BEEFLAMB (0800 233 352) | WWW.BEEFLAMBNZ.COM BY FARMERS. FOR FARMERS Revised and edited by: Dr Ken Geenty Former Research & Development Manager NZ Meat and Wool Producer Boards Beef + Lamb New Zealand would like to acknowledge the writers of 200 by 2000 – A Guide to Improved Lambing Percentage, used as the basis of this book. Prof Paul Kenyon, Dr Trevor Cook and Dr Julie Everett-Hincks provided valuable editorial advice. SUMMARY 2 DEFINITIONS 8 SHEEP REPRODUCTIVE CYCLE 9 CHAPTER ONE 10 An overview of lambing performance on farms CHAPTER TWO 18 Weaning to mating CHAPTER THREE 27 Mating and early pregnancy CHAPTER FOUR 45 Mid to late pregnancy CHAPTER FIVE 59 Lambing CONCLUSIONS 74 APPENDIX 75 Appendix one 76 Appendix two 81 Appendix three 85 Appendix four 88 Appendix five 90 Appendix six 91 SUMMARY MAKING EVERY MATING COUNT CHAPTER 1: AN OVERVIEW OF CHAPTER 2: WEANING TO MATING LAMBING PERFORMANCE ON The period from weaning to mating is important for FARMS preparation of ewes and rams for good reproductive performance. Improved lambing percentage makes the biggest contribution to higher profits on sheep farms. This EWE WEIGHT AND CONDITION FOR MATING chapter covers changes in the sheep industry, lambing performance on farms and changes needed to the A good lambing percentage is largely achieved by farm system with improved lambing percentage. early preparation between weaning and the next mating. CHANGES OVER TIME Ewes need to be in good body weight and condition Sheep industry trends during the 1990s and early 2000s (CS3) for high ovulation rates at mating. -

Reproduction in Sheep and Goats

CHAPTER FIVE Reproduction in Sheep and Goats Girma Abebe Objectives 1. To introduce the basic reproductive tract anatomy and physiology of sheep and goats. 2. To outline causes of reproductive failures. 3. To examine some reproductive traits. Expected Outputs 1. Ability to locate various male and female reproductive structures and describe their respective functions. 2. Ability to list reproductive traits and factors affecting the level of performance. 3. Ability to list common causes of reproductive failures. 4. Adequate understanding to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of seasonal breeding. 5. Ability to discuss and suggest appropriate measures to be taken to improve reproductive efficiency. 6. Ability to list factors responsible for mortality of newly born animals. 7. Knowledge of the management techniques appropriate for different classes of sheep and goats. 60 G IRMA A B E B E 5.1. Introduction Simply defined, reproduction is giving birth to offspring. The survival of a species largely depends on its ability to reproduce its own kind. Reproduction is a series of events (gamete production, fertilization, gestation, reproductive behavior, lambing/kidding, etc.) that terminates when a young is born. Hence, reproduction is a vital function of all living organisms. Reproduction is a complex process. Sheep and goats are considered to be the most prolific of all domestic ruminants. Reproduction determines several aspects of sheep and goat production and an understanding of reproduction is crucial in reproductive management. A high rate of reproductive efficiency is important for: ••• Perpetuation of the species, ••• Production of meat, milk, skin and fiber, and ••• Replacement of breeding stock. Males and females play different reproductive roles, and in most animal species, the role of females is not completed until a viable offspring is produced. -

Implications of Bovine Viral Diseases for Udder Health

REVIEW ARTICLE Implications of bovine viral diseases for udder health As implicações das doenças virais para a saúde da glândula mamária bovina Aline de Jesus da SILVA1; Fernando Nogueira de SOUZA1; Maiara Garcia BLAGITZ1; Camila Freitas BATISTA1; Jéssyca Beraldi BELLINAZZI1; Deisiane Soares Murta NOBRE1; Kamila Reis SANTOS1; Alice Maria Melville Paiva DELLA LIBERA1 1 Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia, Departamento de Clínica Médica, São Paulo – SP, Brazil Abstract Several factors can affect bovine mammary gland health and although bacterial mastitis is the most studied and reported cause, viral infections may also have negative effects on bovine udder health. Viral infections can indirectly damage the papillary duct of the teat, and induce or exacerbate signs of bovine mastitis due to viral-induced immunosuppressive effects that may lead to a greater susceptibility to bacterial mastitis and even intensify the severity of established bacterial infections. Some viruses (Bovine alphaherpesvirus 2, cowpox, pseudocowpox, foot-and-mouth disease, vesicular stomatitis and papillomavirus) affect the integrity of the udder skin, leading to teat lesions, favoring the entry of mastitis-causing pathogens. It is therefore possible that the association between mastitis and viruses is underestimated and may, for example, be associated with negative bacterial culture results. Few milk samples are tested for the presence of viruses, mainly because of the more laborious and expensive procedures required. Furthermore, samples for virus testing would require specific procedures in terms of collection, handling and storage. Thus, there is a knowledge gap in regard to the actual impact of viruses on bovine udder health. Despite the fact that serum anti-virus antibodies can be detected, there is not enough evidence to confirm or exclude the effect of viruses on udder health. -

Mastitis, Mammary Gland Immunity, and Nutrition Daniela Resende Bruno, DVM, Phd Texas Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory - Amarillo

The Mid-South Ruminant Nutrition Conference does not support one product over another and any mention herein is meant as an example, not an endorsement. Mastitis, Mammary Gland Immunity, and Nutrition Daniela Resende Bruno, DVM, PhD Texas Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory - Amarillo INTRODUCTION the mastitis depends on the animal response to the insult, for example the entrance and installation of the Although intensive research and prevention pathogen inside the gland, and on virulence factors measures have been carried out for decades to control present on the bacteria. bovine mastitis, it continues to cause the biggest economic impact to the dairy industry worldwide. There are various genetic, physiological, and Severe economic losses, which are estimated to be environmental factors that can compromise host approximately $200/cow/yr in the United States, are defense mechanisms during the functional transitions due to reduced milk production, discarded milk, of the mammary gland (Sordillo, 2005). Nowadays, replacement costs, extra labor, treatment, and the lactating cow has been genetically selected to veterinary service costs (Smith and Hogan, 2001). In produce more milk, which is the basis of the dairy addition, mastitis increases the risk of antibiotic industry. However this increase in milk volume residues in milk due to treatments and decreases milk metabolically stresses dairy cows and affects quality due to an increase in somatic cell count, as mammary gland immunity by impairing defense well as proteolytic and lipolytic enzymes, which mechanisms decreasing the resistance to mastitis increase the enzymatic breakdown of milk protein (Heringstad et al., 2003). In addition, the milking and fat (National Mastitis Council, 1991).