How Brucite May Affect the Frictional Properties of Serpentinite by Diane E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fluid Mixing and the Deep Biosphere of a Fossil Lost City-Type Hydrothermal System at the Iberia Margin

Fluid mixing and the deep biosphere of a fossil Lost City-type hydrothermal system at the Iberia Margin Frieder Kleina,1, Susan E. Humphrisb, Weifu Guob, Florence Schubotzc, Esther M. Schwarzenbachd, and William D. Orsia aDepartment of Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543; bDepartment of Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543; cDepartment of Geosciences and Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, 28334 Bremen, Germany; and dDepartment of Geosciences, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061 Edited by David M. Karl, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, and approved August 4, 2015 (received for review March 7, 2015) Subseafloor mixing of reduced hydrothermal fluids with seawater is aging, brucite undersaturated in seawater dissolves and aragonite believed to provide the energy and substrates needed to support recrystallizes to calcite (7). deep chemolithoautotrophic life in the hydrated oceanic mantle (i.e., Actively venting chimneys host a microbial community with a serpentinite). However, geosphere-biosphere interactions in serpen- relatively high proportion of methanogenic archaea (the Lost tinite-hosted subseafloor mixing zones remain poorly constrained. City Methanosarcinales), methanotrophic bacteria, and sulfur- Here we examine fossil microbial communities and fluid mixing oxidizing bacteria, whereas typical sulfate-reducing bacteria are processes in the subseafloor of a Cretaceous Lost City-type hydro- rare (8–10). Geochemical evidence for significant microbial sulfate thermal system at the magma-poor passive Iberia Margin (Ocean reduction in basement lithologies and distinct microbial commu- Drilling Program Leg 149, Hole 897D). Brucite−calcite mineral assem- nities in Lost City vent fluids and chimneys suggest that subsurface blages precipitated from mixed fluids ca. -

DOGAMI Short Paper 8, Strategic and Critical Minerals: a Guide for Oregon

STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES 702 Woodlark Building Portland, Oregon G M I SHORT PAPI:R No. 8 STRATEGIC AND CRITICAL MINERALS A GUIDE lOR OREGON PROSPECTORS. By Lloyd w. Staples; Ph.D, A••latant Proteaaor ot Geology University ot Oregon . • STATE GOVIEIIINING BOAIIID W. H. ITRAYIER, CHAIIIMAN . BAKU ALBIEIIIT BURC:H MIEDP'OIID IE MACNAUGHTON ••• PDIIT\.ANO EARL K. NIXON DIIIIIECTOIII PRICIE 15 CIENTI I Oat lORD In noraal tia•• ao1t pro•p•otor• look tor gold, 1inoe that aetal u1ually otter• the �uiok••t reward and i• generally tither •a•1ly reoogn1�•d or the or• 1• •usoept• 1ble or •••Y detera1nat1on. Pro1peotor11 ln general, thus gain llttlt or no experl tno• with other •inerai• who•• peaoetlae aarkttl otter little tnoentlve tor ltaroh tor new depo1it1. Under war oondltion• th••• aineral11 needed tor produotion ot war aat erial•, beooae ot priae iaportanoe and an in1i1tent deaand i1 created tor intoraation oonoernins ooourrenoe11 aineral oharaoteri1tio11 u1e1 and aarket1. fhe Dtpartaent i1 publllhins thil paper to help aeet thil deaand in1otar &I Oreson i1 �ono�rned. Dr. Staple• 11 tlptoially qualititd to write on the lubJeot or 1trateg1o aineral1. In rtoent rear• auoh ot hll work, both 1n private praotioe and 1n teaohing1 hat been oonoerntd with thll tubJeot. It 11 boptd that tht paptr will bt ot aattrial &1111t¬ to Oregon pro1ptotor1 &1 well al to 1aall operator• who have turned their attention troa gold aintns to thole alneral depo1it1 e11ential tor war netdl. It i1 believed that 1ohool1 will al1o t1nd the paper intoraatlve and tiaely. -

Experimental Investigations of the Reaction Path in the Mgo–CO2

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Applied Geochemistry Applied Geochemistry 23 (2008) 1634–1659 www.elsevier.com/locate/apgeochem Experimental investigations of the reaction path in the MgO–CO2–H2O system in solutions with various ionic strengths, and their applications to nuclear waste isolation Yongliang Xiong *, Anna Snider Lord Sandia National Laboratories, Carlsbad Programs Group, 4100 National Parks Highway, Carlsbad, NM 88220, USA1 Received 26 June 2007; accepted 25 December 2007 Editorial handling by Z. Cetiner Available online 9 February 2008 Abstract The reaction path in the MgO–CO2–H2O system at ambient temperatures and atmospheric CO2 partial pressure(s), especially in high-ionic-strength brines, is of both geological interest and practical significance. Its practical importance lies mainly in the field of nuclear waste isolation. In the USA, industrial-grade MgO, consisting mainly of the mineral peri- clase, is the only engineered barrier certified by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for emplacement in the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) for defense-related transuranic waste. The German Asse repository will employ a Mg(OH)2- based engineered barrier consisting mainly of the mineral brucite. Therefore, the reaction of periclase or brucite with car- bonated brines with high-ionic-strength is an important process likely to occur in nuclear waste repositories in salt forma- tions where bulk MgO or Mg(OH)2 will be employed as an engineered barrier. The reaction path in the system MgO–CO2– H2O in solutions with a wide range of ionic strengths was investigated experimentally in this study. The experimental results at ambient laboratory temperature and ambient laboratory atmospheric CO2 partial pressure demonstrate that hyd- romagnesite (5424) (Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2 Á 4H2O) forms during the carbonation of brucite in a series of solutions with differ- ent ionic strengths. -

Brucite Mg(OH)2 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1

Brucite Mg(OH)2 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Hexagonal. Point Group: 32/m. Crystals tabular {0001}, to 19 cm, in platy or foliated masses and rosettes; also fibrous, to 50 cm; granular, massive. Physical Properties: Cleavage: {0001}, perfect. Tenacity: Sectile; separable plates are flexible, fibers are elastic. Hardness = 2.5 D(meas.) = 2.39 D(calc.) = 2.368 Pyroelectric. Optical Properties: Transparent. Color: White, pale green, blue, gray; honey-yellow to brownish red and deep brown in manganoan varieties; colorless in transmitted light. Streak: White. Luster: Waxy, pearly on cleavage surfaces. Optical Class: Uniaxial (+); anomalously biaxial. ω = 1.56–1.59 = 1.58–1.60 2V(meas.) = Small. Cell Data: Space Group: P 3m1..a = 3.142(1) c = 4.766(2) Z=1 X-ray Powder Pattern: Synthetic. 2.365 (100), 4.77 (90), 1.794 (55), 1.573 (35), 1.494 (18), 1.373 (16), 1.310 (12) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) Fe2O3 0.10 1.95 FeO 9.57 MnO 0.84 MgO 68.29 60.33 69.11 H2O 30.74 28.60 30.89 Total 99.97 100.45 100.00 (1) Wood’s Chrome mine, Pennsylvania, USA; corresponds to (Mg0.99Fe0.01)Σ=1.00(OH)2. (2) Asbestos, Canada; after deduction of Fe2O3 impurity, corresponds to 2+ (Mg0.93Fe0.08)Σ=1.01(OH)2. (3) Mg(OH)2. Mineral Group: Brucite group. Occurrence: A common alteration of periclase in marble; a low-temperature hydrothermal vein mineral in metamorphic limestones and chlorite schists; formed during serpentinization of dunites. -

Granasen, a Dolomite-Brucite Deposit with Potential for Industrial Development

NGU -BULL 436, 2000 - PAGE 75 Granasen, a dolomite-brucite deposit with potential for industrial development ODD 0VERENG 0vereng, O. 2000: Granasen, a do lomite-brucite deposi t wi th pote ntial for indust rial develo pm ent. Norges geolog iske und ersekelse Bulletin 436, 75-84. Granasen, situated close to Mo sjoen in north ern Norway, is a deposit containing several milli on tonn es of dolomite and brucite. The deposit has been investig ated and characte rised in preparati on fo r future deve lopment and exploitation. The ore consists of dol omi te and brucite . Brucite has fo rmed as a result of hydro th ermal alte rat ion associated with intrusion of gabbro. Tests have been carried out to evaluate the com mercial value of the dolom ite resources. A variet y of different bene ficiation met hods were investigated to achieve co mmerc ial concent rates of brucite . The most successful result was obtai ned by selective flocculat ion , w hich up-gr ades th e ore to a maximum gra de of 95.5 % brucite, with a recovery of 80 %. As an alte rnative, or by-product of bru cite concent rate produ ction, th e deposit cou ld also be w orked for dolomite. Odd 0vereng, Norgesgeologi ske undersekelse,N-749 1 Trondh eim, Norw ay. of th e Granasen dol om it e marble (Faye & 0 vereng 1979). Introduction Extensive mi neralogical and geo log ical investigat ions, Since the beg inning of the 1970s, the Geologica l Survey of including diamond drill ing, were carried out in 1979 and Norway (NGU) has investigated a large number of indu strial 1980 (0 vereng 1981), and confirmed th e interpretation th at min eral occurrence s. -

Minerals Found in Michigan Listed by County

Michigan Minerals Listed by Mineral Name Based on MI DEQ GSD Bulletin 6 “Mineralogy of Michigan” Actinolite, Dickinson, Gogebic, Gratiot, and Anthonyite, Houghton County Marquette counties Anthophyllite, Dickinson, and Marquette counties Aegirinaugite, Marquette County Antigorite, Dickinson, and Marquette counties Aegirine, Marquette County Apatite, Baraga, Dickinson, Houghton, Iron, Albite, Dickinson, Gratiot, Houghton, Keweenaw, Kalkaska, Keweenaw, Marquette, and Monroe and Marquette counties counties Algodonite, Baraga, Houghton, Keweenaw, and Aphrosiderite, Gogebic, Iron, and Marquette Ontonagon counties counties Allanite, Gogebic, Iron, and Marquette counties Apophyllite, Houghton, and Keweenaw counties Almandite, Dickinson, Keweenaw, and Marquette Aragonite, Gogebic, Iron, Jackson, Marquette, and counties Monroe counties Alunite, Iron County Arsenopyrite, Marquette, and Menominee counties Analcite, Houghton, Keweenaw, and Ontonagon counties Atacamite, Houghton, Keweenaw, and Ontonagon counties Anatase, Gratiot, Houghton, Keweenaw, Marquette, and Ontonagon counties Augite, Dickinson, Genesee, Gratiot, Houghton, Iron, Keweenaw, Marquette, and Ontonagon counties Andalusite, Iron, and Marquette counties Awarurite, Marquette County Andesine, Keweenaw County Axinite, Gogebic, and Marquette counties Andradite, Dickinson County Azurite, Dickinson, Keweenaw, Marquette, and Anglesite, Marquette County Ontonagon counties Anhydrite, Bay, Berrien, Gratiot, Houghton, Babingtonite, Keweenaw County Isabella, Kalamazoo, Kent, Keweenaw, Macomb, Manistee, -

Mineralogy of the Kraubath-Type Magnesite Deposits Of

Yerbilimleri, 30 (3), 169–180 Hacettepe Üniversitesi Yerbilimleri Uygulama ve Araştırma Merkezi Dergisi Journal of the Earth Sciences Application and Research Centre of Hacettepe University Mineralogy of the Kraubath-type magnesite deposits of the Khuzdar area, Balochistan, Pakistan Khuzdar Bölgesi (Belucistan, Pakistan)’ndeki Kraubath tipi manyezit yataklarının mineralojisi Erum BASHIR, Shahid NASEEM, Shamim Ahmed SHEIKH, Maria KALEEM Department of Geology, University of Karachi, Karachi 75270, PAKISTAN Geliş (received) : 17 Ağustos (August) 2009 Kabul (accepted) : 17 Eylül (September) 2009 ABSTRACT Mineralogical studies of the magnesite deposits in the Khuzdar District, Balochistan, Pakistan were made using the X- ray diffraction (XRD) technique. These Kraubath-type magnesite deposits are hosted within serpentinized harzburgites, associated with Bela Ophiolite of Cretaceous age. The deposits occur as cryptocrystalline veins of stockwork-type, possessing botryoidal and bone habits. The ultramafic rocks of Bela Ophiolite were subjected to serpentinization. The hydrothermal fluids leached out Mg, Ca, Fe and other elements from the serpentinized rocks and finally carbonation of these ions resulted in the formation of their hydroxides and carbonates of different combinations to produce these de- posits. The XRD analysis of the ores revealed a high magnesite content in association with artinite, brucite, huntite, Fe- magnesite, dolomite, calcite and Mg-calcite. Initially, at low temperatures and low partial pressure from carbon dioxide (PCO2), metastable hydroxides and carbonates are formed, and these are gradually converted into a stable magnesite phase. The low abundance of allied minerals reflects the relatively high temperature conditions and PCO2 that convert metastable minerals into their stable magnesite phase. The study revealed an increasing temperature and PCO2 from brucite through artinite, hydromagnesite, huntite, and dolomite to magnesite. -

Clay Minerals

CLAY MINERALS CD. Barton United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Aiken, South Carolina, U.S.A. A.D. Karathanasis University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, U.S.A. INTRODUCTION of soil minerals is understandable. Notwithstanding, the prevalence of silicon and oxygen in the phyllosilicate structure is logical. The SiC>4 tetrahedron is the foundation Clay minerals refers to a group of hydrous aluminosili- 2 of all silicate structures. It consists of four O ~~ ions at the cates that predominate the clay-sized (<2 |xm) fraction of apices of a regular tetrahedron coordinated to one Si4+ at soils. These minerals are similar in chemical and structural the center (Fig. 1). An interlocking array of these composition to the primary minerals that originate from tetrahedral connected at three corners in the same plane the Earth's crust; however, transformations in the by shared oxygen anions forms a hexagonal network geometric arrangement of atoms and ions within their called the tetrahedral sheet (2). When external ions bond to structures occur due to weathering. Primary minerals form the tetrahedral sheet they are coordinated to one hydroxyl at elevated temperatures and pressures, and are usually and two oxygen anion groups. An aluminum, magnesium, derived from igneous or metamorphic rocks. Inside the or iron ion typically serves as the coordinating cation and Earth these minerals are relatively stable, but transform- is surrounded by six oxygen atoms or hydroxyl groups ations may occur once exposed to the ambient conditions resulting in an eight-sided building block termed an of the Earth's surface. Although some of the most resistant octohedron (Fig. -

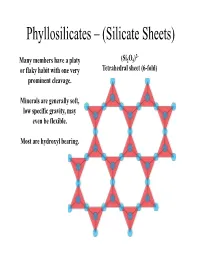

Phyllosilicates – (Silicate Sheets)

Phyllosilicates – (Silicate Sheets) 2- Many members have a platy (Si2O5) or flaky habit with one very Tetrahedral sheet (6-fold) prominent cleavage . Minerals are generally soft, low specific gravity, may even be flexible. Most are hydroxyl bearing. Each tetrahedra is bound to three neiggghboring tetrahedra via three basal bridging oxygens. The apical oxygen of each tetrahedral in a sheet all point in the same direction. The sheets are stacked either apice-to- apice or base-to-base. In an undistorted sheet the hydroxyl (OH) group sits in the centre and each outlined triangle is equivalent. Sheets within sheets…. Apical oxygens, plus the –OH group, coordinate a 6-fold (octahedral) site (XO6). These octahedral sites form infinitely extending sheets. All the octahedra lie on triangular faces, oblique to the tetrahedral sheets. The most common elements found in the 6 -fold site are Mg (or Fe) or Al . Dioctahedral vs Trioctahedral Mg and Al have different charges, but the sheet must remain charge neutral . With 6 coordinating oxygens, we have a partial charge of -6. How many Mg2+ ions are required to retain neutrality? How many Al3+ ions are required to retain neutrality? Mg occupies all octahedral sites, while Al will only occupy 2 out of every 3. The stacking of the sheets dictates the crystallography and c hem istry o f eac h o f t he p hhyll llosili cates. Trioctahedral Dioctahedral O Brucite Gibbsite Hydroxyl Magnesium Aluminium Trioctahedral Is this structure charge neutral? T O T Interlayer Cation T O T Potassium (K+) Phlogopite (Mg end-member biotite) Dioctahedral Is this structure charge neutral? T O T Interlayer Cation T O T Potassium (K+) Muscovite Compositional variation in phyllosilicates There is little solid solution between members of the dioctahedral and trioctahedral groups. -

Analysis of Martin Marietta Magchem 10 WTS-60 Mgo

Page 1 of 28 Sandia National Laboratories Waste Isolation Pilot Plant Analysis of Martin Marietta MagChem 10 WTS-60 MgO Haoran Deng,1 Shelly Johnsen,1 Yongliang Xiong,1 Gregory T. Roselle,1 and Martin Nemer2 1. Repository Performance Dept. 6712 2. Performance Assessment and Decision Analysis Dept. 6711 Sandia National Laboratories Carlsbad Programs Group Carlsbad, NM 88220 WIPP:1.4.1.2:PA:QA-L:543261 Page 2 of 28 APPROVAL PAGE Author: Haoran Deng, 6712 Date Author: Shelly Johnsen, 6712 Date Author: Yongliang Xiong, 6712 Date Author: Gregory T. Roselle, 6711 Date Author: Martin Nemer, 6711 Date Technical Reviewer: Daniel Clayton, 6712 Date QA Reviewer: Mario J. Chavez, 6710 Date Management Reviewer: Mark Rigali, 6712 Date WIPP:1.4.1.2:PA:QA-L:543261 Page 3 of 28 TABLE OF CONTENTS APPROVAL PAGE.........................................................................................................................2 TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................................................................................................3 LIST OF TABLES...........................................................................................................................4 LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................5 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 6 2 NOMENCLATURE ................................................................................................................... -

The Intergrowth of Fibrous Brucite and Fibrous

Canadian Mineralogist Vol. 17, pp.699-7V2 (1979) THE INTERGROWTHOF FIBROUSBRUCITE AND FIBROUSMAGNESITE WITH CHRVSOTILE E. J. W. WHITTAKER AND A. P. MIDDLETON Depanment of Geology and Mineralogy, University of Oxford, Parks Road, Oxford lXI 3PR, England ABsrRAcr de Jeffrey rappelle Ia soi-disantn6malite de Cassiar, C.B., qui consisteen mas6site fibreuse avec chry' Nemalite (fibrous brucite) from Jeffrey mine, sotile accessoire,et dans laquelle l'orientation va- Qu6bec, has been investigated by electron micro- riable des fibrilles de magn6site s'expliquerait par ssopy and diffraction. The material consists of an des consid6rationsst6riques plut6t que structurales. association of fibrous brucite with chrysotile-2itf.r and paraohrysotile. The brucite is present in laths (Traduit par la Rddaction) elongated along the .r axis and not invariably lying on (0001). The laths are associated with fibrils of chrysotile had been a common initial constituent of hqtnopucttoN orientation of tle nemalite would correspond to the orientation of the outer brucite-like layer of the fibrils, and therefore be dependent on whether Nemalite, a fibrous form of brucite, was those fibrils are normal or parachrysotile. Elonga- first described by Nuttall (1821). It commonly tion of the laths is frequently opposite to that occurs in slip-fibre veins in serpentine; the predicted. This may be due to the fact that para- fibres can be very longo some specimens ap- chrysotile had been a corrmon initial constituent of proaching a length of 3 m, although the distance the material during the formation of the brucite, but that it subsequently recrystallued to more over which fibres are continuous is difficult to stable normal chrysotile. -

Studies on the Mechanisms of Alkali ".'Carbonate Reaction Part I. Chemical Reactions

Studies on the Mechanisms of Alkali ".'Carbonate Reaction Part I. Chemical Reactions W. CULLEN SHERWOOD and HOWARD H. NEWLON, JR., respectively, Geologist and Highway Research Engineer, Virginia Council of Highway Investigation and Research •AN understanding of the mechanisms of alkali-carbonate rock reaction which result in expansion of concrete is of primary importance in dealing with the resultant prob lems on a practical level. This paper reports results of laboratory studies made to determine the contributory chemical reactions that may take place. Results of parallel studies on such physical aspects as internal structure of and access of alkalies into various carbonate rock types are not included, but will be published at a later date. The method of approach has been to consider each of the three major minerals or groups of minerals that normally make up carbonate rocks; i.e., quartz, clays and carbonates. These were investigated through studies of pure minerals, as well as re active and non-reactive rocks, to determine what possible role each might play in ob served expansion in the composite system. These major constituents were analyzed and measured by a variety of methods to determine chemical composition, phase composition, and volume and mass of the ma terials before and after exposure to sodium and potassium hydroxide solutions. (Mass and weight are used interchangeably throughout this paper.) Evidences of reactions noted during this portion of the study were then sought in thin sections, test prisms, and in aggregate from laboratory and field concrete. MINERALS AND ROCKS UTILIZED The calcite and dolomite minerals used in this study were high-purity coarsely crystalline materials.