Agrifood Atlas: Facts and Figures About the Corporations That Control What

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United-2016-2021.Pdf

27010_Contract_JCBA-FA_v10-cover.pdf 1 4/5/17 7:41 AM 2016 – 2021 Flight Attendant Agreement Association of Flight Attendants – CWA 27010_Contract_JCBA-FA_v10-cover.indd170326_L01_CRV.indd 1 1 3/31/174/5/17 7:533:59 AMPM TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 Recognition, Successorship and Mergers . 1 Section 2 Definitions . 4 Section 3 General . 10 Section 4 Compensation . 28 Section 5 Expenses, Transportation and Lodging . 36 Section 6 Minimum Pay and Credit, Hours of Service, and Contractual Legalities . 42 Section 7 Scheduling . 56 Section 8 Reserve Scheduling Procedures . 88 Section 9 Special Qualification Flight Attendants . 107 Section 10 AMC Operation . .116 Section 11 Training & General Meetings . 120 Section 12 Vacations . 125 Section 13 Sick Leave . 136 Section 14 Seniority . 143 Section 15 Leaves of Absence . 146 Section 16 Job Share and Partnership Flying Programs . 158 Section 17 Filling of Vacancies . 164 Section 18 Reduction in Personnel . .171 Section 19 Safety, Health and Security . .176 Section 20 Medical Examinations . 180 Section 21 Alcohol and Drug Testing . 183 Section 22 Personnel Files . 190 Section 23 Investigations & Grievances . 193 Section 24 System Board of Adjustment . 206 Section 25 Uniforms . 211 Section 26 Moving Expenses . 215 Section 27 Missing, Interned, Hostage or Prisoner of War . 217 Section 28 Commuter Program . 219 Section 29 Benefits . 223 Section 30 Union Activities . 265 Section 31 Union Security and Check-Off . 273 Section 32 Duration . 278 i LETTERS OF AGREEMENT LOA 1 20 Year Passes . 280 LOA 2 767 Crew Rest . 283 LOA 3 787 – 777 Aircraft Exchange . 285 LOA 4 AFA PAC Letter . 287 LOA 5 AFA Staff Travel . -

Friday July 14, 2017 At

Friday July 14, 2017 Central Valley buying Group Page 1 of 49 Bid effective 7-1-2017 thru 6-30-2018 Brand names and numbers when used or for reference to indicate the character or quality desired. Equal item will be considered provided your offer clearly describes the article> Offer for equal item shall state the brand name and number or level of quality if item cannot be identified by brand name and number. brand prod code Vendor Code Purchase unit Purchase Unit Purchase Price Totals Rebates and Pack Size Brand Description MPC Code Qty description Quantity or notes Dairy Products 2 1 DZ FROZFRT BAR FRUIT CHUNKY PNAPL 4.0 1050488 3 24 4OZ BLU BNY BAR FRUIT STWBRY FRZN 61 4 4.25LB WHLFIMP BUTTER CHIP CNTL SLTD 47 CT AA 6060 5 5 3.4 LB WHLFIMP BUTTER CHIP CNTL USDA AA 59CT 6061 1 720 5 GM WHLFIMP BUTTER CUP USDA AA 4509 2 30 1LB WHLFCLS BUTTER SOLID SLTD AA 310521 21 30 1 LB WHLFCLS BUTTER SOLID UNSLTD AA 310522 13 6 .5 GAL WHLFCLS BUTTERMILK 1% LOW FAT 2832 2 4 5 LB BBRLCLS CHEESE AMER 120 DELI SLI YEL STK03324 6 4 5 LB BBRLCLS CHEESE AMER 120 SLI YEL 28131 38 4 5 LB BBRLCLS CHEESE AMER 160 DELI SLI YEL 34947 129 4 5 LB BBRLCLS CHEESE AMER 160 SLI YEL 28128 6 4 5 LB BONGARD CHEESE AMER PPRJACK 120 SLICE 10341 2 4 5LB SCHRBER CHEESE AMER YEL 160 SLI 8367 4 4 5LB CASASOL CHEESE CHDR MILD FCY SHRD YEL 960319 90 4 5LB CASASOL CHEESE CHDR MILD FTHR SHRD YEL 960320 87 4 5LB CASASOL CHEESE CHEDDAR JACK FTHR SHRED 960322 17 100 .75OZ BBRLIMP CHEESE CHEDDAR MLD MINI YEL IW STK05014 4 4 2.5 LB ROTHKAS CHEESE CHEDDAR SLICE .75 OZ 5550 2 2 5LB BBRLIMP CHEESE CHEDDR MILD LOAF YEL 99234 2 168 1 OZ HERITG CHEESE COLBY JACK STICKS I/W 32879 54 2 5 LB WHLFCLS CHEESE COTTAGE SMALL CURD 2% 3395900 8 100 1 OZ BBRLIMP CHEESE CREAM CUP PLAIN 39801 64 100 .75 OZ BBRLIMP CHEESE CREAM CUP STRAWBERRY 39782 21 4 3 LB SYS IMP CHEESE CREAM LOAF 39837 7 100 1 OZ PHILA CHEESE CREAM ORIG SPREAD CUP 61119 3 4 3 LB BBRLIMP CHEESE CREAM WHIPPED TUB 39847 3 5 LB BBRLIMP CHEESE CUBE CHDR/SWISS/PEP JCK 98940 12 192 3 OZ. -

The “Panhollow” Dispersal Sale

The “Panhollow” Dispersal Sale Of 500 Pedigree Holstein Friesians On behalf of Rodney, Jean & Paul Allin MONDAY 14TH SEPTEMBER 2020 9.45am HOLSWORTHY MARKET New Market Road, Holsworthy, Devon, EX22 7FA The “Panhollow” Dispersal Sale of 500 Pedigree Holstein Friesians on behalf of Rodney, Jean & Paul Allin Hollow Panson, St Giles On The Heath, Launceaston (removed to Holsworthy Livestock Market for convenience of sale) Comprising: 365 In Milk and/or In Calf Cows & Heifers, and 130 “A” lot Heifer Calves to follow their dams. Monday 14th September 2020 9.45am at HOLSWORTHY MARKET New Market Road, Holsworthy, Devon, EX22 7FA FOREWORD On behalf of Kivells we would like to thank Rodney, Jean and Paul Allin for their kind instructions to disperse their ‘Panhollow’ herd of 500 Pedigree Holstein Friesian dairy cattle at Holsworthy Market on Monday 14th September at Holsworthy Market. The sale of 500 head of Dairy Cattle will be the largest one day sale to have occurred in Devon and Cornwall for some considerable time. Quantity and quality combines to provide this wonderful selection from one holding. When Rodney left school the farm carried 50 cows and followers, 300 sheep, with 140 acres of cereals. For Rodney’s 21st birthday he was given a pedigree heifer calf and over the next few years the existing herd was graded up and a few pedigree animals were purchased. The herd expanded with quality breeding and is entirely homebred. In 1999 the opportunity to acquire the farm from Emma, Col. Molesworth St. Aubyn’s daughter, and the Tetcott Estate arose. Rodney and Jean’s son, Paul, joined the business having completed three years at Bicton College and the family commenced the expansion of the dairy herd. -

Product List - - 1800 854 234

Product List - www.TheProfessors.com.au - 1800 854 234 Allens Marella Jubes (1.3kg bag) Red Vines - Original Red Twists (1 tray x 141g) Bubblicious Fruit Twist Gum (18 packs x 5 gum pieces) Allens Marella Jubes Saver Pack (4 x 190g Bags) Red Vines - Original Red Twists (12 trays x 141g) Bubblicious Watermelon Gum (18 packs x 5 gum pieces) Hershey's Kisses (12 x 150g bags) Allens Milk Bottles (1.3kg bag) Red Vines - Original Red Twists (6 trays x 141g) Cadbury Boost Stix Twin Bar (55g x 30) Sixlets - Black- ( Bulk 4.5kg box) Allens Milko Chews (3kg bag) Red Vines 4lbs tub (240pc - unwrapped red vines in a display tub) Cadbury Buzz (42 x 20g bars in a Display Unit) Sixlets - Gold- ( Bulk 4.5kg box) Allens Milkos (150 Stick Display Unit) Cadbury Caramello Block (10 x 110g blocks) Sixlets - Lime Green- ( Bulk 4.5kg box) Allens Minties (1 kg Bag) Cadbury Caramello Koala (72 x 20gm in a Display Unit) Sweetworld Jelly Pencils (12 x400g hang sell bags) Arnotts Allens Party Mix (1.3 kg Bag) Arnotts Tim Tam Fingers (28 x 40g packs) Cadbury Caramello Rolls (36 x 55g Rolls) AB Food and Beverages Allens Pineapples (1.3kg bag) Arnotts Wagon Wheels (16 x 48g biscuits) Cadbury Cherry Ripe (48 x 52g bars in a display unit) Allens Racing Cars (1.3kg bag) Cadbury Chocolate Fish (42 x 20g in a Display Unit) Ovalteenies (24 bags in a Display Unit) Allens Retro Party Mix (1kg bag) Bassett Cadbury Chomp Caramel Bars (50 bars in Display Unit) AIT Confectionery Allens Ripe Raspberries (1.3kg Bag) Bassetts Pear Drops (12 x 200g bags) Cadbury Crunchie (42 x 50g -

Cargill Premix & Nutrition: Transforming Talent Management

Cargill Premix & Nutrition: Transforming Talent Management Michael Gunderson Associate Professor and Associate Director of Research Center for Food and Agricultural Business, Purdue University Wes Davis Graduate Assistant Center for Food and Agricultural Business, Purdue University This case was prepared by Michael Gunderson, associate professor and associate director of research, and Wes Davis, graduate assistant, Center for Food and Agricultural Business, Purdue University. The authors would like to thank Cargill Premix & Nutrition, particularly Heather Imel, vice president of human capital, Cargill Premix & Nutrition North America. The case is a basis for class discussion and represents the views of the authors, not Purdue University. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without written permission from Purdue University. 2 | Cargill Premix & Nutrition: Transforming Talent Management © 2017 Purdue Univerisity In early 2016 Charles Shininger, managing director for Cargill Premix & Nutrition North America, takes part in a leadership meeting with other business unit managers and platform leaders at Cargill’s global headquarters in Minneapolis. Having just completed a successful quarter, he looks forward to reviewing the global enterprise’s performance and discussing business plans for the year. As the meeting begins, the global executive team of nine corporate officers discusses overall performance. Cargill has experienced declining annual operating earnings since 2011 (Exhibit 1). Some business units have performed well; however, changing customer preferences, political and regulatory uncertainty, macroeconomic challenges, and reinvented customer business models have eroded overall enterprise earnings and led the global executive team to consider what changes are necessary to reclaim performance. Exhibit 1: Over the last six years, operating earnings have been suppressed compared to FY 2011. -

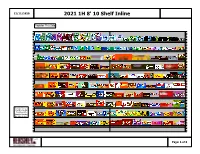

2021 1H 4' 10 Shelf Inline

12/11/2020 2021 1H 8' 10 Shelf Inline Register This Side Replace Reese's Crunchy Cookie Cup King with Reese's Crunchy Bar King in April Page: 1 of 6 12/11/2020 2021 1H 8' 10 Shelf Inline Register This Side 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Shelf: 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Shelf: 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Shelf: 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Shelf: 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Shelf: 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Shelf: 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Shelf: 4 Replace Reese's 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Crunchy Cookie Shelf: 3 Cup King with Reese's Crunchy Bar King in April 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Shelf: 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Shelf: 1 Page: 2 of 6 12/11/2020 2021 1H 8' 10 Shelf Inline Segment-Packtype Mints Bottle & Mega Gum Nonchocolate King and Standard Chocolate King Singles Gum Chocolate Standard Register This Side EXTRA EXTRA EXTRA ICE ICE ICE ICE ICE ICE ICE TRIDENT TRIDENT REFRESHE REFRESHE REFRESHE BREAKERS BREAKERS BREAKERS BREAKERS BREAKERS BREAKERS BREAKERS VIBES S/F MENTOS MENTOS MENTOS VIBES R RS RS S/F CUBE S/F CUBE S/F CUBE S/F CUBE S/F CUBE S/F CUBE S/F CUBE SPEARMINT PURE FRESH PURE FRESH PURE WHITE EXTRA EXTRA 5 COBALT S/F POLAR BERRY 5 RAIN PEPPERMI SPEARMIN WNTRGRN ARCTIC RASPBRY CINN BLK CHR S/F GUM - FRESH GUM - S/F GM SWT SPEARMINT 5 SPRMNT ICE MIX TRIDENT POLAR 35PC 5 RAIN 5 5 DENTYNE TROP BT SPEARMINT MNT 35PC NT T GRAPE SORBT MINT 50PC GUM SGR ICE 35PC 35PC -

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 2019 Ag Partners Cooperative Inc Ag

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 2019 Ag Partners Cooperative Inc Ag Valley Coop AgReliant Genetics Agri Beef Co AgriVision Equipment Group Altec Industries Archer Daniels Midland Company (ADM) Ardent Mills Buhler Inc. Cargill Central Valley Ag Cooperative Commstock Investments Conagra Brands Consolidated Grain and Barge Co ConocoPhillips Corteva Agriscience Didion Milling Elanco Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company H&R Block Hills Pet Nutrition Hormel Foods Iowa Select Farms John Deere Kiewit Louis Dreyfus Company Medxcel Mueller Industries, Inc. Murphy-Hoffman Company (MHC Kenworth) NEW Cooperative, Inc. Northwestern Mutual Financial Network - The RPS Financial Group PepsiCo Phillips 66 PrairieLand Partners Smithfield Spring Venture Group Syngenta (Sales and Agronomy) Target Corporation (Target Stores) Textron The Greensman Inc The Hershey Company The Schwan's Company The Scoular Company Timberline Landscaping, Inc. Union Pacific Railroad THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 26, 2019 Apex Energy Solutions Archer Daniels Midland Company (ADM) Bayer U.S. LLC Cargill Cintas Colgate-Palmolive ConocoPhillips DEG Digital East Daley Capital Elanco empirical foods, inc. Five Rivers Cattle Feeding H&R Block (Finance) Hills Pet Nutrition Hormel Foods Insight Global Irsik & Doll Feed Services, Inc. Land O'Lakes, Inc. Murphy Family Ventures Murphy-Hoffman Company (MHC Kenworth) Netsmart Technologies, Inc. PepsiCo Phillips 66 Seaboard Foods The Schwan's Company Union Pacific Railroad FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2019 3M Alliance Construction Solutions, LLC Altec Industries Ardent Mills Ash Grove Cement Company Austin Bridge & Road, L.P Bimbo Bakeries USA Black & Veatch Blattner Energy, Inc. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas Buildertrend CannonDesign Cargill Chevron Phillips Chemical CHS Cintas Colgate-Palmolive Conagra Brands Emerson (Emerson Automations Solutions - Flow Controls) EvapTech, Inc. -

Saga Jacques Vabre/P.27-34

PAR JEAN WATIN-AUGOUARD (saga ars, de l’or en barre Mars, ou comment une simple pâte à base de lait, de sucre et d’orge recouverte d’une couche de caramel, le tout enrobé d’une fine couche de chocolat au lait est devenue la première barre chocolatée mondiale et l’un des premiers produits nomades dans l’univers de la confiserie. (la revue des marques - n°46 - avril 2004 - page 27 saga) Franck C. Mars ne reçu jamais le moindre soutien des banques et fit de l’autofinancement une règle d’or, condition de sa liberté de créer. Celle-ci est, aujourd’hui, au nombre des cinq principes du groupe . Franck C. Mars, 1883-1934 1929 - Franck Mars ouvre une usine ultramoderne à Chicago est une planète pour certains, le dieu de la guerre pour d’autres, une confiserie pour tous. Qui suis-je ?… Mars, bien sûr ! Au reste, Mars - la confiserie -, peut avoir les trois sens pour les mêmes C’ personnes ! La planète du plaisir au sein de laquelle trône le dieu Mars, célèbre barre chocolatée dégustée dix millions de fois par jour dans une centaine de pays. Mars, c’est d’abord le patronyme d’une famille aux commandes de la société du même nom depuis quatre générations, société - cas rare dans l’univers des multinationales -, non côtée en Bourse. Tri des œufs S’il revient à la deuxième génération d’inscrire la marque au firmament des réussites industrielles et commerciales exemplaires, et à la troisième de conquérir le monde, la première génération peut se glorifier d’être à l’origine d’une recette promise à un beau succès. -

Cargill Non-GMO Solutions

Cargill Non-GMO Solutions Cargill helps customers grow and protect their brands, and reduce time-to-market Non-GMO* is one of the Food category growth rates fastest growing claims in % growth of $ sales over prior year the U.S. food industry.1 12% 11% 11% A recent Cargill study showed that GMO is top 10% of mind when consumers are asked what they avoid when purchasing food. For over 15 years Cargill has helped customers navigate supply-chain challenges, source non-GMO ingredients, and grow their 2% non-GMO business. 1% 1% 1% 2012 2013 2014 2015 From dedicated producer programs to the industry’s broadest ingredient Total (+1% CAGR) portfolio, Cargill is the right Non-GMO Organic Natural (+11% CAGR) partner to help food and beverage manufacturers grow and protect Source: White Wave at 2016 CAGNY Conference their brands by delivering non-GMO products to consumers. 1 Source: Mintel, March 2016 Cargill.com/food-beverage Cargill markets the industry’s broadest portfolio of non-GMO ingredients. From sweeteners, starches and texturizers to oils, cocoa and chocolate, Cargill delivers the scale that food manufacturers need to get to market quickly and meet growing consumer demand. We offer a growing number of Non-GMO Project Verified ingredients so customers can feature America’s most recognizable non-GMO claim on their labels. Well-established producer programs for corn, soybeans and high oleic canola means unsurpassed supply chain assurance for our customers. Limited supply of non-GMO corn, soybeans and high oleic canola creates challenges for food and beverage companies seeking to scale production and meet growing consumer demand. -

Corn Has Diverse Uses and Can Be Transformed Into Varied Products

Maize Based Products Compiled and Edited by Dr Shruti Sethi, Principal Scientist & Dr. S. K. Jha, Principal Scientist & Professor Division of Food Science and Postharvest Technology ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, Pusa New Delhi 110012 Maize is also known as Corn or Makka in Hindi. It is one of the most versatile crops having adaptability under varied agro-climatic conditions. Globally, it is known as queen of cereals due to its highest genetic yield potential among the cereals. In India, Maize is grown throughout the year. It is predominantly a kharif crop with 85 per cent of the area under cultivation in the season. The United States of America (USA) is the largest producer of maize contributing about 36% of the total production. Production of maize ranks third in the country after rice and wheat. About 26 million tonnes corn was produced in 2016-17 from 9.6 Mha area. The country exported 3,70,066.11 MT of maize to the world for the worth of Rs. 1,019.29 crores/ 142.76 USD Millions in 2019-20. Major export destinations included Nepal, Bangladesh Pr, Myanmar, Pakistan Ir, Bhutan The corn kernel has highest energy density (365 kcal/100 g) among the cereals and also contains vitamins namely, vitamin B1 (thiamine), B2 (niacin), B3 (riboflavin), B5 (pantothenic acid) and B6. Although maize kernels contain many macro and micronutrients necessary for human metabolic needs, normal corn is inherently deficient in two essential amino acids, viz lysine and tryptophan. Maize is staple food for human being and quality feed for animals. -

Is There a World Beyond Supermarkets? Bought These from My Local Farmers’ My Local Box Market Scheme Delivers This I Grew These Myself!

www.ethicalconsumer.org EC178 May/June 2019 £4.25 Is there a world beyond supermarkets? Bought these from my local farmers’ My local box market scheme delivers this I grew these myself! Special product guide to supermarkets PLUS: Guides to Cat & dog food, Cooking oil, Paint feelgood windows Enjoy the comfort and energy efficiency of triple glazed timber windows and doors ® Options to suit all budgets Friendly personal service and technical support from the low energy and Passivhaus experts www.greenbuildingstore.co.uk t: 01484 461705 g b s windows ad 91x137mm Ethical C dec 2018 FINAL.indd 1 14/12/2018 10:42 CAPITAL AT RISK. INVESTMENTS ARE LONG TERM AND MAY NOT BE READILY REALISABLE. ABUNDANCE IS AUTHORISED AND REGULATED BY THE FINANCIAL CONDUCT AUTHORITY (525432). add to your without arming rainy day fund dictators abundance investment make good money abundanceinvestment.com Editorial ethicalconsumer.org MAY/JUNE 2019 Josie Wexler Editor This is a readers choice issue – we ask readers to do ethical lifestyle training. We encourage organisations and an online survey each Autumn on what they’d like us networks focussed on environmental or social justice to cover. It therefore contains guides to some pretty issues to send a representative. disparate products – supermarkets, cooking oil, pet food and paint. There is also going to be a new guide to rice Our 30th birthday going up on the web later this month. As we mentioned in the last issue, it was Ethical Animal welfare is a big theme in both supermarkets and Consumer’s 30th birthday in March this year. -

Private & Confidential

Private & Confidential SAARF AMPS 2008B 2008B Rolling Average Release Layout (Jan - Dec '08) ADULTS with Branded Products PRELIMINARY Prepared for:- South African Advertising Research Foundation (SAARF®) Copyright Reserved Mar-09 SAARF COPYRIGHT The copyright of this report is reserved under the Copyright Act of the Republic of South Africa. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any means or used in any form by persons or organisations other than the members of the South African Advertising Research Foundation (SAARF) without the prior written permission of the Chief Executive Officer of the Foundation. Members of the Foundation who reproduce or publish information from the SAARF AMPS® Reports should make clear reference to the source of such information and should lodge a copy or details of the material reproduced or published with the Chief Executive Officer of the Foundation at the time of its release. No use or attempted use of data published in or derived from any of the SAARF AMPS® family of research reports in a court of law is permissible. SAARF AMPS® data may not be used in governmental proceedings except with the explicit permission of SAARF; such permission shall be sought in advance for clearly defined purposes separately in every instance. Private and Confidential SAARF AMPS® 2008B SECTION (2008B Rolling Average Release Layout) Prepared for: South Africa Advertsing Research Foundation (SAARF) Prepared by: Shonigani - Nielsen Media Research (An operating division of ACNielsen Marketing and Media (Pty) Ltd.) ® 2009/03/16 SAARF AMPS 2008B AMPS ® 2008B CD PAGE A TECHNICAL DATA Informants : 21083 Adult Population : 31305 H/Hold Weight : 11139 Cards Per : 1-49,51,52,54,55,56,68,73-75,91-93,202-299,300-311,501-504 Questionnaire Questionnaire No.