China's Engagement-Oriented Strategy Towards North Korea: Achievements and Limitations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Korea's Nuclear Weapons Development and Diplomacy

North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons Development and Diplomacy Larry A. Niksch Specialist in Asian Affairs January 5, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33590 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons Development and Diplomacy Summary Since August 2003, negotiations over North Korea’s nuclear weapons programs have involved six governments: the United States, North Korea, China, South Korea, Japan, and Russia. Since the talks began, North Korea has operated nuclear facilities at Yongbyon and apparently has produced weapons-grade plutonium estimated as sufficient for five to eight atomic weapons. North Korea tested a plutonium nuclear device in October 2006 and apparently a second device in May 2009. North Korea admitted in June 2009 that it has a program to enrich uranium; the United States had cited evidence of such a program since 2002. There also is substantial information that North Korea has engaged in collaborative programs with Iran and Syria aimed at producing nuclear weapons. On May 25, 2009, North Korea announced that it had conducted a second nuclear test. On April 14, 2009, North Korea terminated its participation in six party talks and said it would not be bound by agreements between it and the Bush Administration, ratified by the six parties, which would have disabled the Yongbyon facilities. North Korea also announced that it would reverse the ongoing disablement process under these agreements and restart the Yongbyon nuclear facilities. Three developments -

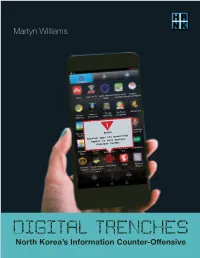

Digital Trenches

Martyn Williams H R N K Attack Mirae Wi-Fi Family Medicine Healthy Food Korean Basics Handbook Medicinal Recipes Picture Memory I Can Be My Travel Weather 2.0 Matching Competition Gifted Too Companion ! Agricultural Stone Magnolia Escpe from Mount Baekdu Weather Remover ERRORTelevision the Labyrinth Series 1.25 Foreign apps not permitted. Report to your nearest inminban leader. Business Number Practical App Store E-Bookstore Apps Tower Beauty Skills 2.0 Chosun Great Chosun Global News KCNA Battle of Cuisine Dictionary of Wisdom Terms DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive Copyright © 2019 Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior permission of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 435 Washington, DC 20036 P: (202) 499-7970 www.hrnk.org Print ISBN: 978-0-9995358-7-5 Digital ISBN: 978-0-9995358-8-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019919723 Cover translations by Julie Kim, HRNK Research Intern. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gordon Flake, Co-Chair Katrina Lantos Swett, Co-Chair John Despres, -

University of West Bohemia in Pilsen Faculty of Philosophy and Arts

University of West Bohemia in Pilsen Faculty of Philosophy and Arts Dissertation Thesis Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in International Politics Analysis of the Changes of North Korean Foreign Policy between 1994 and 2015 Using the Role Theoretic Approach Plzeň 2016 Lenka Caisová University of West Bohemia in Pilsen Faculty of Philosophy and Arts Department of Politics and International Relations Study Programme Political Science Field of Study International Relations Dissertation Thesis Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in International Politics Analysis of the Changes of North Korean Foreign Policy between 1994 and 2015 Using the Role Theoretic Approach Lenka Caisová Supervisor: doc. PhDr. Šárka Cabadová-Waisová, Ph.D. Department of Politics and International Relations University of West Bohemia in Pilsen Sworn Statement I hereby claim I made this dissertation thesis (topic: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in International Politics ; subtopic: Analysis of the Changes of North Korean Foreign Policy between 1994 and 2015 Using the Role Theoretic Approach ) together with enclosed codebook by myself whereas I used the sources as stated in the Bibliography only. In certain parts of this thesis I use extracts of articles I published before. In Chapter 1 and 2, I use selected parts of my article named “ Severní Korea v mezinárodních vztazích: jak uchopovat severokorejskou zahraniční politiku? ” which was published in Acta FF 7, no. 3 in 2014. In Chapter 4, I use my article named “Analysis of the U.S. Foreign Policy towards North Korea: Comparison of the Post-Cold War Presidents” which was published in Acta FF no. 3, 2014 and article named “ Poskytovatelé humanitární a rozvojové pomoci do Korejské lidově demokratické republiky ” published in journal Mezinárodní vztahy 49, no. -

North Korea-South Korea Relations: Back to Belligerence

Comparative Connections A Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations North Korea-South Korea Relations: Back to Belligerence Aidan Foster-Carter Leeds University, UK For almost the whole of the first quarter of 2008, official inter-Korean relations were largely suspended in an uneasy limbo. As of late March, that void was the story. Up to a point this was only to be expected. A new conservative leader in Seoul – albeit a pragmatist, or so he tells us – was bound to arouse suspicion in Pyongyang at first. Also, Lee Myung-bak needed some time to settle into office and find his feet. Still, it was remarkable that this limbo lasted so long. More than three months after Lee’s landslide victory in the ROK presidential elections on Dec. 19, DPRK media – which in the past had no qualms in dubbing Lee’s Grand National Party (GNP) as a bunch of pro- U.S. flunkeys and national traitors – had made no direct comment whatsoever on the man Pyongyang has to deal with in Seoul for the next five years. Almost the sole harbinger of what was to come – a tocsin, in retrospect – was a warning snarl in mid-March against raising North Korean human rights issues. One tried to derive some small comfort from this near-silence; at least the North did not condemn Lee a priori and out of hand. In limbo Yet the hiatus already had consequences. Perhaps predictably, most of the big inter- Korean projects that Lee’s predecessor, the center-left Roh Moo-hyun, had rushed to initiate in his final months in office after his summit last October with the North’s leader, Kim Jong-il, barely got off the ground. -

Prace Orientalistyczne I Afrykanistyczne 2 Papers in Oriental and African Studies

PRACE ORIENTALISTYCZNE I AFRYKANISTYCZNE N. Levi Korea Północna Zarys ewolucji systemu politycznego 2 PAPERS IN ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES 1 PRACE ORIENTALISTYCZNE I AFRYKANISTYCZNE 2 PAPERS IN ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES 2 Nicolas Levi Korea Północna zarys ewolucji systemu politycznego Warszawa 2016 3 PRACE ORIENTALISTYCZNE I AFRYKANISTYCZNE 2 Wydawnictwo Instytutu Kultur Śródziemnomorskich i Orientalnych Polskiej Akademii Nauk ul. Nowy Świat 72, Pałac Staszica, 00-330 Warszawa tel.: +4822 657 27 91, [email protected]; www.iksiopan.pl Recenzenci: dr hab. Anna Antczak-Barzan dr hab Grażyna Strnad Copyright by Instytut Kultur Śródziemnomorskich i Orientalnych PAN and Nicolas Levi Redakcja techniczna i korekta językowa: Dorota Dobrzyńska Fotografie: Nicolas Levi Opracowanie graficzne, skład i łamanie DTP: MOYO - Teresa Witkowska ISBN: 978-83-943570-2-3 Druk i oprawa: Oficyna Wydawniczo-Poligraficzna i Reklamowo-Handlowa ADAM. ul. Rolna 191/193; 02-729 Warszawa 4 Spis treści Wstęp 7 Transkrypcja słów koreańskich 11 Słowniczek podstawowych pojęć i terminów 11 Wykaz najważniejszych skrótów 12 1. Rozwój ruchu komunistycznego na Półwyspie Koreańskim 13 1.1. Narodziny Partii Pracy Korei Północnej 13 1.1.1. Powstanie północnokoreańskiego ruchu komunistycznego 13 1.1.2. Frakcje i komunizm na Półwyspie Koreańskim 14 1.1.3. Czystki w koreańskich frakcjach komunistycznych 19 1.2. Organizacja polityczna społeczeństwa 24 1.2.1. System kimirsenowski 24 1.2.2. Ideologia Dżucze 31 1.2.3. Koncept „dynastii” północnokoreańskiej i kult jednostki 37 2. Północnokoreańskie organizacje polityczne i wojskowe 49 2.1. Analiza struktury organizacji politycznych w Korei 49 Północnej 2.1.1. Demokratyczny Front Na Rzecz Zjednoczenia Ojczyzny 49 2.1.2. -

Comparative Connections a Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations

Comparative Connections A Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations North Korea-South Korea Relations: Squeezing the Border Aidan Foster-Carter Leeds University, UK Looking back, it was a hostage to fortune to title our last quarterly review: “Things can only get better?” Even with that equivocating final question mark, this was too optimistic a take on relations between the two Koreas – which, as it turned out, not only failed to improve but deteriorated further in the first months of 2009. Nor was that an isolated trend. This was a quarter when a single event – or more exactly, the expectation of an event – dominated the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia more widely. Suspected since January, announced in February and awaited throughout March, despite all efforts to dissuade it North Korea’s long-anticipated Taepodong launched on April 5. This too evoked a broader context, and a seeming shift in Pyongyang. Even by the DPRK’s unfathomable logic, firing a big rocket – satellite or no – seemed a rude and perverse way to greet a new U.S. president avowedly committed to engagement with Washington’s foes. Yet, no fewer than four separate senior private U.S. delegations, visiting Pyongyang in unusually swift succession during the past quarter, heard the same uncompromising message. Even veteran visitors who fancied they had good contacts found the usual access denied and their hosts tough-minded: apparently just not interested in an opportunity for a fresh start offered by a radically different incumbent of the White House. Not mending but building fences Speculation on the reasons for this newly negative stance – paralleled by a reversion to hardline policies on the home front also, as in efforts to rein in markets (with mixed success) – is beyond the scope of this article. -

Double-Sidedness of North Korea

Double-sidedness of North Korea Chang Yong-seok (Senior Researcher, Institute for Peace and Unification Studies of Seoul National University) Jeong Eun-mee (Humanities Korea Research Professor, Institute for Peace and Unification Studies of Seoul National University) CHAPTER 1: WHY DOUBLE- SIdedneSS? 5 CHAPTER 2: DOUBLE-SIdedneSS IN POLITICS·MILItarY 1. People’s democracy and hereditary dictatorship 10 2. A powerful and prosperous country and backwardness 24 3. Independence line and dependency on foreign countries 40 4. National cooperation and provocations against South Korea 52 CHAPTER 3: DOUBLE-SIdedneSS IN ECONOMY·SOCIetY 1. Planned economy and private economic activity 66 2. Distribution system and the market 80 3. Egalitarian society and discrimination by Songbun (North Korea’s social classification system) 91 4. Pyongyang, the “capital of the revolution,” and the provinces 102 CHAPTER 4: DOUBLE-SIdedneSS IN PEOPLE’S LIVES·VaLUES 1. Collectivism and individualism 118 2. Official media and informal information 126 3. Social control and aberrations 137 4. Socialism centered on the popular masses and human rights violations 146 CHAPTER 5: COntINUatION and ChanGE OF DOUBLE-SIdedneSS OF NOrth KOrea 157 WHY DOUBLE- SIDEDNESS? CHAPTER 1 WHY DOUBLE- SIDEDNESS? In any society, there is an official or dominating value, ideology and system that serve as a mechanism to integrate the society. At the same time, however, there is a reality that is different from such an official or dominating value and ideology. As the reality changes rapidly, the official or dominating value, ideology and system face pressure to change and in fact must change according to the relationships between a variety of groups and powerful forces in the society. -

In Search of Diaspora Connections: North Korea's Policy Towards Korean Americans, 1973-1979*

International Journal of Korean Unification Studies Vol. 27, No. 2, 2018, 113-141. In Search of Diaspora Connections: North Korea’s Policy towards Korean Americans, 1973-1979* Kelly Un Kyong Hur Since the 1950s, North Korea considered the “overseas compatriot” or haeoe dongpo** issue an important policy agenda under the perception that they could provide political and ideological support and legitimacy for the regime. From the early 1970s, North Korea began to expand the diaspora policy that went beyond the Koreans in Japan to the United States to promote a “worldwide movement of overseas compatriots.” Concomitantly, North Korea launched a public diplomacy campaign toward the U.S. to gain American public support for its political and diplomatic agendas during this period. This public diplomacy towards Americans intersected with the development of a policy towards Koreans residing in the United States. This study explores the development of North Korean policy towards Korean Americans that began to evolve in the 1970s. The historical background behind the evolution of this policy as well as specific policy objectives and strategies are depicted. Ultimately, this policy was focused on engaging with Korean Americans who could act as a link between the two countries with the aspiration that they convey North Korea’s policies to the United States, improve its international image and increase global support for Korean reunification on North Korean terms. I argue that the efforts in the 1970s laid the groundwork that contributed to a formulation of a more tangible policy starting in the late 1980s and early 1990s that included hosting family reunions, group tours to North Korea, cultural and religious exchanges and promoting the establishment of pro-North Korea associations in the United States. -

Musikpädagogik in Nordkorea

Musikpädagogik in Nordkorea Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Humanwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln nach der Promotionsordnung vom 10.05.2010 vorgelegt von Mi-Kyung, Chang aus Seoul (Südkorea) Dezember/2014 Diese Dissertation wurde von der Humanwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln im April 2015 angenommen. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------4 1.1 Forschungsinteresse und Zielsetzung--------------------------------------------4 1.2 Ausblick: Eine positive Rolle der Musikpädagogik für den Wiederverei- nigungsprozess-------------------------------------------------------------------------9 1.3 Zur Forschungs- und Quellenlage------------------------------------------------10 2. Zum historischen Hintergrund: Der Koreakrieg und die endgültige Landesteilung-----------------------------------------------------------------------------14 2.1. Unabhängigkeit und erste Teilung ----------------------------------------------14 2.2. Die Entstehung des Teilungssystems-------------------------------------------18 2.2.1 Regierungsbildung in der Republik Korea------------------------------18 2.2.2 Regierungsgründung im Norden Koreas--------------------------------20 2.2.3 Der Weg zum Koreakrieg---------------------------------------------------22 2.3. Die Situation vor dem Koreakrieg -----------------------------------------------23 2.3.1 Die Lage im Süden-----------------------------------------------------------23 2.3.2 -

Japan's Korean Residents Caught in the Japan-North Korea Crossfire

Volume 5 | Issue 1 | Article ID 2327 | Jan 02, 2007 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Japan's Korean Residents Caught in the Japan-North Korea Crossfire H Matsubara, John Feffer, M Tokita Japan’s Korean Residents Caught in the support. Japan-North Korea Crossfire By Matsubara Hiroshi and Tokita Mayuko Introduction by John Feffer The Asahi Shinbun and the International Herald Tribune recently published a five-part series on Korean residents in Japan. Many of these zainichi – the word literally means “residing in Japan” – have lived in the country for two, three and even four generations. Having been deprived of the Japanese citizenship that they obtained under colonial rule in the years 1910-1945, the 600,000zainichi are those Korean residents who have not become naturalized Japanese citizens. The series shows that they now find themselves in a crossfire between the North Korean and Japanese governments. The zainichi are the largest ethnic minority in a country that often prides itself, mistakenly, on being homogenous. The Asahi series, which uses as a news peg the impact of North Korea’s nuclear test on the Korean community, is fascinating as much for what it reveals as for what it leaves out. It does bravely delve into some sensitive historical questions: the repatriation of zainichi to North Korea beginning in 1959, including the Japanese government role in promoting repatriation, the role of the North Korea-affiliated organization Chosen Soren (Chongryon) in Japan, and the oft- ignored tale of Korean atom bomb victims, including hundreds who returned to North or South Korea and have been ineligible for Japanese government health care and other 1 5 | 1 | 0 APJ | JF had required changing their Korean name to a Japanese one, not only face discrimination but lack citizenship rights despite having been born and educated in Japan and speaking fluent Japanese. -

Current Status of North Korean Teaching Method Following the Changes in Content Deployment Method in Textbooks

S/N Korean Humanities, Volume 3 Issue 2 (September 2017) https://doi.org/10.17783/IHU.2017.3.2.101 pp.101~117∣ISSN 2384-0668 / E-ISSN 2384-0692 ⓒ 2017 IHU S/N Korean Humanities Volume3 Issue2 Current Status of North Korean Teaching Method Following the Changes in Content Deployment Method in Textbooks 33) Oum, Hyun Suk Center for Korean Unification Education in Seoul Abstract This article examines the current status of North Korean teaching method according to the changes in the content deployment in textbooks which were published after Kim Jong-un assumed power. The author examined changes in the content deployment of first-year textbooks for elementary, middle and high schools which were published after Kim Jong-un took power and analyzed how such changes affected the teaching method. For this, the article reviewed periodical publications on North Korean education which were published around 2012 to examine the evaluation of the teacher's group which is directly affected the supplementation of the teaching method. The study focused on the changes in content deployment in textbooks as such changes require assessment on whether they require direct changes to the teaching method. The outcome of the study can be summarized as the following. Firstly, changes in the content deployment methods of textbooks are made in various forms and approaches. Secondly, the way of describing contents has deviated from historical narrative. The change of the teaching method is inevitable as the content deployment methods are transformed to enhance readability and to shift focus from knowledge transfer to activity-oriented manner. -

Handbook for Korean Studies Librarianship Outside of Korea Published by the National Library of Korea

2014 Editorial Board Members: Copy Editors: Erica S. Chang Philip Melzer Mikyung Kang Nancy Sack Miree Ku Yunah Sung Hyokyoung Yi Handbook for Korean Studies Librarianship Outside of Korea Published by the National Library of Korea The National Library of Korea 201, Banpo-daero, Seocho-gu, Seoul, Korea, 137-702 Tel: 82-2-590-6325 Fax: 82-2-590-6329 www.nl.go.kr © 2014 Committee on Korean Materials, CEAL retains copyright for all written materials that are original with this volume. ISBN 979-11-5687-075-3 93020 Handbook for Korean Studies Librarianship Outside of Korea Table of Contents Foreword Ellen Hammond ······················· 1 Preface Miree Ku ································ 3 Chapter 1. Introduction Yunah Sung ···························· 5 Chapter 2. Acquisitions and Collection Development 2.1. Introduction Mikyung Kang·························· 7 2.2. Collection Development Hana Kim ······························· 9 2.2.1 Korean Studies ······································································· 9 2.2.2 Introduction: Area Studies and Korean Studies ································· 9 2.2.3 East Asian Collections in North America: the Historical Overview ········ 10 2.2.4 Collection Development and Management ···································· 11 2.2.4.1 Collection Development Policy ··········································· 12 2.2.4.2 Developing Collections ···················································· 13 2.2.4.3 Selection Criteria ···························································· 13 2.2.4.4