Feathers & Feather Tracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magnificent Magpie Colours by Feathers with Layers of Hollow Melanosomes Doekele G

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb174656. doi:10.1242/jeb.174656 RESEARCH ARTICLE Magnificent magpie colours by feathers with layers of hollow melanosomes Doekele G. Stavenga1,*, Hein L. Leertouwer1 and Bodo D. Wilts2 ABSTRACT absorption coefficient throughout the visible wavelength range, The blue secondary and purple-to-green tail feathers of magpies are resulting in a higher refractive index (RI) than that of the structurally coloured owing to stacks of hollow, air-containing surrounding keratin. By arranging melanosomes in the feather melanosomes embedded in the keratin matrix of the barbules. barbules in more or less regular patterns with nanosized dimensions, We investigated the spectral and spatial reflection characteristics of vivid iridescent colours are created due to constructive interference the feathers by applying (micro)spectrophotometry and imaging in a restricted wavelength range (Durrer, 1977; Prum, 2006). scatterometry. To interpret the spectral data, we performed optical The melanosomes come in many different shapes and forms, and modelling, applying the finite-difference time domain (FDTD) method their spatial arrangement is similarly diverse (Prum, 2006). This has as well as an effective media approach, treating the melanosome been shown in impressive detail by Durrer (1977), who performed stacks as multi-layers with effective refractive indices dependent on extensive transmission electron microscopy of the feather barbules the component media. The differently coloured magpie feathers are of numerous bird species. He interpreted the observed structural realised by adjusting the melanosome size, with the diameter of the colours to be created by regularly ordered melanosome stacks acting melanosomes as well as their hollowness being the most sensitive as optical multi-layers. -

The Molecular Evolution of Feathers with Direct Evidence from Fossils

The molecular evolution of feathers with direct evidence from fossils Yanhong Pana,1, Wenxia Zhengb, Roger H. Sawyerc, Michael W. Penningtond, Xiaoting Zhenge,f, Xiaoli Wange,f, Min Wangg,h, Liang Hua,i, Jingmai O’Connorg,h, Tao Zhaoa, Zhiheng Lig,h, Elena R. Schroeterb, Feixiang Wug,h, Xing Xug,h, Zhonghe Zhoug,h,i,1, and Mary H. Schweitzerb,j,1 aChinese Academy of Sciences Key Laboratory of Economic Stratigraphy and Palaeogeography, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology and Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; bDepartment of Biological Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695; cDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29205; dAmbioPharm Incorporated, North Augusta, SC 29842; eInstitute of Geology and Paleontology, Lingyi University, Lingyi City, 27605 Shandong, China; fShandong Tianyu Museum of Nature, Pingyi, 273300 Shandong, China; gCAS Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100044 Beijing, China; hCenter for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100044 Beijing, China; iCollege of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100049 Beijing, China; and jNorth Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh, NC 27601 Contributed by Zhonghe Zhou, December 15, 2018 (sent for review September 12, 2018; reviewed by Dominique G. Homberger and Chenxi Jia) Dinosaur fossils possessing integumentary appendages of various feathers in Anchiornis, barbules that interlock to form feather morphologies, interpreted as feathers, have greatly enhanced our vanes critical for flight have not been identified yet (12). -

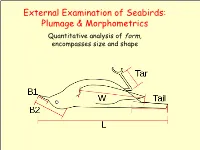

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics Quantitative analysis of form, encompasses size and shape Seabird Topography ➢ Naming Conventions: • Parts of the body • Types of feathers (Harrison 1983) Types of Feathers Coverts: Rows bordering and overlaying the edges of the tail and wings on both the lower and upper sides of the body. Help streamline shape of the wings and tail and provide the bird with insulation. Feather Tracks ➢ Feathers are not attached randomly. • They occur in linear tracts called pterylae. • Spaces on bird's body without feather tracts are called apteria. • Densest area for feather tracks is head and neck. • Feathers arranged in distinct layers: contour feathers overlay down. Generic Pterylae Types of Feathers Contour feathers: outermost feathers. Define the color and shape of the bird. Contour feathers lie on top of each other, like shingles on a roof. Shed water, keeping body dry and insulated. Each contour feather controlled by specialized muscles which control their position, allowing the bird to keep the feathers in clean and neat condition. Specialized contour feathers used for flight: delineate outline of wings and tail. Types of Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Define outline of wings and tail Long and stiff Asymmetrical those on wings are called remiges (singular remex) those on tail are called retrices (singular retrix) Types of Flight Feathers Remiges: Largest contour feathers (primaries / secondaries) Responsible for supporting bird during flight. Attached by ligaments or directly to the wing bone. Types of Flight Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Rectrices: tail feathers provide flight stability and control. Connected to each other by ligaments, with only the inner- most feathers attached to bone. -

Colour De Verre Molds: Feather

REUSABLE MOLDS FOR GLASS CASTING With either product, clean the See our website’s Learn section for mold with a stiff nylon brush and/ more instructions about priming or toothbrush to remove any old Colour de Verre molds with ZYP. kiln wash or boron nitride. (This step can be skipped if the mold is Filling the Feather brand new.) The suggested fill weight for the Feather is 330 to 340 grams. The If you are using Hotline Primo most simple way to fill the Feather Primer, mix the product according mold is to weigh out 330 of fine to directions. Apply the Primo frit and to evenly distribute the frit Primer™ with a soft artist’s brush in the mold. Fire the mold and frit (not a hake brush) and use a hair according the Casting Schedule Feather dryer to completely dry the coat. below. This design is also a perfect Create feathers that are as fanci- Give the mold four to five thin, candidate for our Wafer-Thin ful or realistic as you like with even coats drying each coat with a technique. One can read more Colour de Verre’s Feather de- hair dryer before applying the about this at www.colourdeverre.- sign. Once feathers are cast, next. Make sure to keep the Primo they can be slumped into amaz- com/go/wafer. ing decorative or functional well stirred as it settles quickly. pieces. The mold should be totally dry before filling. There is no reason to nnn pre-fire the mold. To use ZYP, hold the can 10 to 12 Feathers are a design element that inches from the mold. -

Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight

Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight Exhibition Organized and Circulated by: The Dinosaur Museum, Utah The Fossil Administration Office, Liaoning, China Beipiao City Paleontological Research Center, Liaoning, China THE PREHISTORIC WORLD OF LIAONING The fossils of Liaoning represent a complex ecosystem creating a more complete picture of this particular age of dinosaurs than ever before. Life of the Early Cretaceous, 120 million years ago, was far more than a world of dinosaurs. The fossils include a remarkable variety of plants, crustaceans, insects, fish, amphibians, lizards, crocodiles, aquatic reptiles, flying reptiles, as well as birds that could fly and others which were flightless. FEATHERS BEFORE BIRDS Included are graphics and photos which show developmental stages of feathers. The fossil of the flying reptile, Pterorhynchus is preserved with details of what pterosaurs looked like which have never been seen before. The body is covered with down-like feathers which resemble those also found on the dinosaur, Sinosauropteryx. Because feathers are now known to exist on animals other than birds, this discovery changes the definition of what a bird is. Pterorhynchus Sinosauropteryx FLYING DROMAEOSAURS AND THE MISTAKEN IDENTITY Dromaeosaurs have been thought to be ground-dwelling dinosaurs that represented ancestral stages of how birds evolved. Fossils in this exhibit show that they have been misinterpreted as dinosaurs when they are actually birds. Feather impressions reveal that they had flight feathers on the wings and a second set on the hind legs. Even without the feathers preserved, the avian characteristics of the skeleton demonstrate that these dromaeosaurs are birds. This discovery means that the larger dromaeosaurs, like Deinonychus and Velociraptor of “Jurassic Park” fame, were really feathered and are secondarily flightless birds. -

Feather Loss and Feather Destructive Behavior in Pet Birds

REVIEW FEATHER LOSS AND FEATHER DESTRUCTIVE BEHAVIOR IN PET BIRDS Jonathan Rubinstein, DVM, Dip. ABVP (Avian), and Teresa Lightfoot, DVM, Dip. ABVP (Avian) Abstract Feather loss in psittacine birds is an extremely common and extremely frustrating clinical presentation. Causes include medical and non-medical causes of feather loss both with and without overt feather destructive behavior. Underlying causes are myriad and include inappropriate husbandry and housing; parasitic, viral and bacterial infections; metabolic and allergic diseases; and behavioral disorders. Prior to a diagnosis of a behavioral disorder, medical causes of feather loss must be excluded through a complete medical work-up including a comprehensive history, physical exam, and diagnostic testing as indicated by the history, signalment and clinical signs. This article focuses on some of the more common medical and non-medical causes of feather loss and feather destructive behavior as well as approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Copyright 2012 Published by Elsevier Inc. Key words: feather destructive behavior; psittacine; behavioral disorder; feather-picking; avian behavior eather loss is one of the more common and frustrating reasons that avian patients are presented to veterinary hospitals. Several factors make the treatment of feather loss difficult. The initial problem lies in the relative scarcity of controlled studies related to the underlying causes of feather loss in companion avian species and the paucity of current veterinary medical knowledge regarding feather loss and feather destructive behavior (FDB). Although many medical and environmental conditions Fhave been associated with FDB, few have been proven to be causal. Wherever possible, this article references applicable controlled studies, although they are few. -

Avian Feathers Function, Structure & Coloration

A Feather from the Whippoorwill (Emily Dickinson, 1955) A feather from the Whippoorwill That everlasting -- sings! Whose galleries -- are Sunrise – Whose Opera -- the Springs – Whose Emerald Nest the Ages spin Of mellow -- murmuring thread – Whose Beryl Egg, what Schoolboys hunt In "Recess" -- Overhead! Photograph by Robert Clark—Audubon Magazine 2012 Avian Feathers Function, Structure & Coloration • Tremendous Investment – 25,000 on Tundra Swan – 2-4,000 on songbirds – 970 on hummingbird • Feather Mass=2-3X Skeletal Mass • 91% Protein (keratin) 1% Fat, 8% water • Waxy secretions and fatty acids from uropygial gland protect feathers Feather Outline • Functions in addition • Coloration to flight – Pigments – Structural Colors • Structure & Variation • Origin of feather color and recent fossil discoveries Do feathers have a function or are they just an expensive costume? • Insulation • Sound production • Sound capture • Camouflage • Aerodynamics • Sexual selection • Protection • Nesting, diet, other Diverse Functions • Crypticity – Disruptive color patterns in Killdeer and meadowlarks – Mimicry in bitterns, snipe, and woodcock Diverse Functions • Sound production for attraction – Booming of Ruffed Grouse wings – Primary flight feathers of American Woodcock – Hummingbirds • You Tube Hummingbird Music – Manakins • Manakin Wing Sound Diverse Functions • Sound gathering properties of owls and some hawks – Eastern Screech Owl – Northern Harrier (hawk) http://www.wisenaturephotos.com/NEW!!!%202-10-06.htm Diverse Functions • Support – Tail rectrices -

A New Feather Type in a Nonavian Theropod and the Early Evolution of Feathers

A new feather type in a nonavian theropod and the early evolution of feathers Xing Xua,1, Xiaoting Zhengb, and Hailu Youc aLaboratory of Evolutionary Systematics of Vertebrates, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 142 Xiwai Street, Beijing 100044, China; bShandong Tianyu Museum of Nature, Pingyi, Shandong 273300, China; and cInstitute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, 26 Baiwanzhuang Road, Beijing 100037, China Edited by David B. Wake, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved December 8, 2008 (received for review October 7, 2008) All described feathers in nonavian theropods are composite struc- tures formed by multiple filaments. They closely resemble rela- tively advanced stages predicted by developmental models of the origin of feathers, but not the earliest stage. Here, we report a feather type in two specimens of the basal therizinosaur Beipiao- saurus, in which each individual feather is represented by a single broad filament. This morphotype is congruent with the stage I morphology predicted by developmental models, and all major predicted morphotypes have now been documented in the fossil record. This congruence between the full range of paleontological and developmental data strongly supports the hypothesis that feathers evolved and initially diversified in nonavian theropods before the origin of birds and the evolution of flight. Early Cretaceous ͉ filament ͉ display eathers have been documented in most nonavian coeluro- Fsaurian theropod groups, based mainly on recent discoveries of exceptionally well-preserved specimens from the Early Cre- taceous Jehol Group of western Liaoning, China (1–4). The feathers present in these specimens can be categorized into several morphotypes, but all of them are composite structures formed by multiple slender filaments (5–7). -

Birds of a Feather — Coping With

THE SEA GRANT and GOMRI BIRDS OF A FEATHER — COPING WITH OIL PARTNERSHIP Emily Maung-Douglass, Larissa Graham, Christine Hale, Stephen Sempier, The mission of Sea Grant is Tara Skelton, LaDon Swann, and Monica Wilson to enhance the practical use and conservation of coastal, marine, and Great Lakes resources in order to create Although birds can travel great distances, they cannot necessarily a sustainable economy and escape oil exposure from natural oil seeps or oil spills caused by humans. environment. There are 33 Scientists and natural resource managers are still trying to understand university–based Sea Grant programs throughout the the many ways oil exposure can affect birds. coastal U.S. These programs are primarily supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the states in which the programs are located. In the immediate aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon spill, BP committed $500 million over a 10–year period to create the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative, or GoMRI. It is an independent research program that studies the effect of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as develops improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization, and remediation technologies. GoMRI is led by an independent and academic 20–member research board. The Sea Grant oil spill science outreach team identifies the best available science from Though an entirely land-based species of bird, seaside sparrows showed signs of oil in their projects funded by GoMRI and others, and only shares peer- diet after Deepwater Horizon oil spill. (Andrea Bonisoli Alquati) reviewed research results. Oil can have a variety of short- and long- individual birds to die, but it can also term effects on birds, including damage lower overall population numbers by to plumage, poor health, delayed reducing breeding, hatching, nesting 1 Texas • Louisiana • Florida migration, and death. -

The Origin and Diversification of Birds

Current Biology Review The Origin and Diversification of Birds Stephen L. Brusatte1,*, Jingmai K. O’Connor2,*, and Erich D. Jarvis3,4,* 1School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Grant Institute, King’s Buildings, James Hutton Road, Edinburgh EH9 3FE, UK 2Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 3Department of Neurobiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, USA 4Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD 20815, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] (S.L.B.), [email protected] (J.K.O.), [email protected] (E.D.J.) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.003 Birds are one of the most recognizable and diverse groups of modern vertebrates. Over the past two de- cades, a wealth of new fossil discoveries and phylogenetic and macroevolutionary studies has transformed our understanding of how birds originated and became so successful. Birds evolved from theropod dino- saurs during the Jurassic (around 165–150 million years ago) and their classic small, lightweight, feathered, and winged body plan was pieced together gradually over tens of millions of years of evolution rather than in one burst of innovation. Early birds diversified throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous, becoming capable fliers with supercharged growth rates, but were decimated at the end-Cretaceous extinction alongside their close dinosaurian relatives. After the mass extinction, modern birds (members of the avian crown group) explosively diversified, culminating in more than 10,000 species distributed worldwide today. Introduction dinosaurs Dromaeosaurus albertensis or Troodon formosus.This Birds are one of the most conspicuous groups of animals in the clade includes all living birds and extinct taxa, such as Archaeop- modern world. -

A Densely Feathered Ornithomimid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, Canada: a Comment

Cretaceous Research xxx (2015) 1e4 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Cretaceous Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/CretRes Discussion A densely feathered ornithomimid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, Canada: A comment Theagarten Lingham-Soliar Environmental Sciences, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Summerstrand, Port Elizabeth 6001, South Africa article info abstract Article history: The presence of feathers in Ornithomimus is questioned on poor evidence and a failure to observe sci- Received 25 November 2015 entific process and procedure. Accepted in revised form 4 December 2015 © 2016 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Available online xxx Keywords: Ornithomimus Feathers Collagen fibres Biology Taphonomy 1. Introduction establishing rachidial widths of their alleged feathers (innumerable according to the authors reconstructions in figs. 3, 5, 6), the authors van der Reest et al. (2016) describe an Ornithomimus with have provided no statistical measurements. This is conflated by a alleged plumaceous feathers including reconstructions/in- vague reference to the ‘feather’ width range of between 0.2 and terpretations; most of latter will not be considered in any detail in 0.5 mm and to a solitary example “on the body of UALVP 52531 is this commentary for reasons that will become clear in my 0.4 mm laterally (their fig. 4b and c).”This leaves no option but to concluding remarks. I shall, however, examine independently, trust to the scale bar on their fig. 4 and to try to establish what they where possible, the paleontological evidence behind the authors mean by feathers in the context of width and structure, at least in interpretations. -

The Early Origin of Feathers

Trends in Ecology & Evolution Review The Early Origin of Feathers Michael J. Benton,1,* Danielle Dhouailly,2 Baoyu Jiang,3 and Maria McNamara4 Feathers have long been regarded as the innovation that drove the success of Highlights birds. However, feathers have been reported from close dinosaurian relatives of Feathers are epidermal appendages birds, and now from ornithischian dinosaurs and pterosaurs, the cousins of dino- comprising mostly corneous β-proteins saurs. Incomplete preservation makes these reports controversial. If true, these (formerly β-keratins), and are characteris- tic of birds today. findings shift the origin of feathers back 80 million years before the origin of birds. Gene regulatory networks show the deep homology of scales, feathers, and hairs. There are close connections in terms of Hair and feathers likely evolved in the Early Triassic ancestors of mammals and genomic regulation between numerous birds, at a time when synapsids and archosaurs show independent evidence of regularly arrayed structures in the epider- mis, including denticles in sharks, dermal higher metabolic rates (erect gait and endothermy), as part of a major resetting of scales in teleost fish, epidermal scales in terrestrial ecosystems following the devastating end-Permian mass extinction. reptiles, feathers in birds, and hairs in mammals. Early Origin of Feathers The discovery that genes specifictothe It is shocking to realise that feathers originated long before birds because feathers have generally production of feathers evolved at the – base of Archosauria rather than the been regarded as the key avian innovation [1 4]. However, thousands of astonishing fossils from base of Aves or Avialae (birds) is China have shown that many nonavian dinosaurs (see Glossary) also had feathers, including matched by fossil evidence that feathers feather types not found in birds today.