A Bizarre Early Cretaceous Enantiornithine Bird with Unique Crural Feathers and an Ornithuromorph Plough-Shaped Pygostyle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Late Cretaceous)

Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw | 87 - 4 | 353 - 358 | 2008 Geo (Im) pulse Bird remains from the Maastrichtian type area (Late Cretaceous) G.J. Dyke1*, A.S. Schulp2 & J.W.M. Jagt2 1 School of Biology and Environmental Sciences, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland. 2 Natuurhistorisch Museum Maastricht, De Bosquetplein 6-7, NL-6211KJ Maastricht, the Netherlands. * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Manuscript received: June 2007; accepted: October 2008 Abstract Remains of Late Cretaceous birds are rare, which is especially true for Europe and the type area of the Maastrichtian Stage (southeast Netherlands, northeast Belgium) in particular. In the present paper, we record new remains (isolated tarsometatarsus and radius) that document the presence of both enantiornithine and ornithurine birds in the Maastrichtian area. These fossils, although fragmentary, are important in view of their stratigraphic age: all bird remains discovered to date in the Maastricht area are amongst the youngest 'non-modern' avians known, originating from strata deposited less than 500,000 years prior to the end of the Cretaceous Period. Keywords: Aves, Enantiornithes, Ornithurae, Maastrichtian, Late Cretaceous, the Netherlands, Belgium Introduction In general, the fossil record of birds from the latest stages of the Cretaceous is more scanty and less well understood than Despite more than 250 years of intensive collecting effort in that of the Lower and 'Middle' Cretaceous (Chiappe & Dyke, shallow marine sediments in the type area of the Maastrichtian 2002; Chiappe & Witmer, 2002; Fountaine et al, 2005). In Stage (southeast Netherlands, northeast Belgium; Fig. 1), the particular, Late Cretaceous birds are rare in Europe (see Dyke first bird remains to be recognised from this part of Europe et al, 2002; Rees & Lindgren, 2005): the bulk of the material have been described only relatively recently. -

The Phylogenetic Position of Ambiortus: Comparison with Other Mesozoic Birds from Asia1 J

ISSN 00310301, Paleontological Journal, 2013, Vol. 47, No. 11, pp. 1270–1281. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2013. The Phylogenetic Position of Ambiortus: Comparison with Other Mesozoic Birds from Asia1 J. K. O’Connora and N. V. Zelenkovb aKey Laboratory of Evolution and Systematics, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, 142 Xizhimenwai Dajie, Beijing China 10044 bBorissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Profsoyuznaya ul. 123, Moscow, 117997 Russia email: [email protected], [email protected] Received August 6, 2012 Abstract—Since the last description of the ornithurine bird Ambiortus dementjevi from Mongolia, a wealth of Early Cretaceous birds have been discovered in China. Here we provide a detailed comparison of the anatomy of Ambiortus relative to other known Early Cretaceous ornithuromorphs from the Chinese Jehol Group and Xiagou Formation. We include new information on Ambiortus from a previously undescribed slab preserving part of the sternum. Ambiortus is superficially similar to Gansus yumenensis from the Aptian Xiagou Forma tion but shares more morphological features with Yixianornis grabaui (Ornithuromorpha: Songlingorni thidae) from the Jiufotang Formation of the Jehol Group. In general, the mosaic pattern of character distri bution among early ornithuromorph taxa does not reveal obvious relationships between taxa. Ambiortus was placed in a large phylogenetic analysis of Mesozoic birds, which confirms morphological observations and places Ambiortus in a polytomy with Yixianornis and Gansus. Keywords: Ornithuromorpha, Ambiortus, osteology, phylogeny, Early Cretaceous, Mongolia DOI: 10.1134/S0031030113110063 1 INTRODUCTION and articulated partial skeleton, preserving several cervi cal and thoracic vertebrae, and parts of the left thoracic Ambiortus dementjevi Kurochkin, 1982 was one of girdle and wing (specimen PIN, nos. -

A Second Cretaceous Ornithuromorph Bird from the Changma Basin, Gansu Province, Northwestern China Author(S): Hai-Lu You , Jessie Atterholt , Jingmai K

A Second Cretaceous Ornithuromorph Bird from the Changma Basin, Gansu Province, Northwestern China Author(s): Hai-Lu You , Jessie Atterholt , Jingmai K. O'Connor , Jerald D. Harris , Matthew C. Lamanna and Da-Qing Li Source: Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 55(4):617-625. 2010. Published By: Institute of Paleobiology, Polish Academy of Sciences DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2009.0095 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.4202/app.2009.0095 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. A second Cretaceous ornithuromorph bird from the Changma Basin, Gansu Province, northwestern China HAI−LU YOU, JESSIE ATTERHOLT, JINGMAI K. O’CONNOR, JERALD D. HARRIS, MATTHEW C. LAMANNA, and DA−QING LI You, H.−L., Atterholt, J., O’Connor, J.K., Harris, J.D., Lamanna, M.C., and Li, D.−Q. 2010. A second Cretaceous ornithuromorph bird from the Changma Basin, Gansu Province, northwestern China. -

Uropygial Gland in Birds

UROPYGIAL GLAND IN BIRDS Prepared by Dr. Subhadeep Sarker Associate Professor, Department of Zoology, Serampore College Occurrence and Location: • The uropygial gland, often referred to as the oil or preen gland, is a bilobed gland and is found at the dorsal base of the tail of most psittacine birds. • The uropygial gland is a median dorsal gland, one per bird, in the synsacro-caudal region. A half moon-shaped row of feather follicles of the upper median and major tail coverts externally outline its position. • The uropygial area is located dorsally over the pygostyle on the midline at the base of the tail. • This gland is most developed in waterfowl but very reduced or even absent in many parrots (e.g. Amazon parrots), ostriches and many pigeons and doves. Anatomy: • The uropygial gland is an epidermal bilobed holocrine gland localized on the uropygium of most birds. • It is composed of two lobes separated by an interlobular septum and covered by an external capsule. • Uropygial secretory tissue is housed within the lobes of the gland (Lobus glandulae uropygialis), which are nearly always two in number. Exceptions occur in Hoopoe (Upupa epops) with three lobes, and owls with one. Duct and cavity systems are also contained within the lobes. • The architectural patterns formed by the secretory tubules, the cavities and ducts, differ markedly among species. The primary cavity can comprise over 90% of lobe volume in the Oilbird (Steatornis caripensis) and some woodpeckers and pigeons. • The gland is covered by a circlet or tuft of down feathers called the uropygial wick in many birds. -

New Tyrannosaur from the Mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan Clarifies Evolution of Giant Body Sizes and Advanced Senses in Tyrant Dinosaurs

Edinburgh Research Explorer New tyrannosaur from the mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan clarifies evolution of giant body sizes and advanced senses in tyrant dinosaurs Citation for published version: Brusatte, SL, Averianov, A, Sues, H, Muir, A & Butler, IB 2016, 'New tyrannosaur from the mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan clarifies evolution of giant body sizes and advanced senses in tyrant dinosaurs', Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, pp. 201600140. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1600140113 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1073/pnas.1600140113 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 Classification: Physical Sciences: Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences; Biological Sciences: Evolution New tyrannosaur from the mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan clarifies evolution of giant body sizes and advanced senses in tyrant dinosaurs Stephen L. Brusattea,1, Alexander Averianovb,c, Hans-Dieter Suesd, Amy Muir1, Ian B. Butler1 aSchool of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3FE, UK bZoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. -

New Oviraptorid Dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Nemegt Formation of Southwestern Mongolia

Bull. Natn. Sci. Mus., Tokyo, Ser. C, 30, pp. 95–130, December 22, 2004 New Oviraptorid Dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Nemegt Formation of Southwestern Mongolia Junchang Lü1, Yukimitsu Tomida2, Yoichi Azuma3, Zhiming Dong4 and Yuong-Nam Lee5 1 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100037, China 2 National Science Museum, 3–23–1 Hyakunincho, Shinjukuku, Tokyo 169–0073, Japan 3 Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum, 51–11 Terao, Muroko, Katsuyama 911–8601, Japan 4 Institute of Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China 5 Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources, Geology & Geoinformation Division, 30 Gajeong-dong, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 305–350, South Korea Abstract Nemegtia barsboldi gen. et sp. nov. here described is a new oviraptorid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous (mid-Maastrichtian) Nemegt Formation of southwestern Mongolia. It differs from other oviraptorids in the skull having a well-developed crest, the anterior margin of which is nearly vertical, and the dorsal margin of the skull and the anterior margin of the crest form nearly 90°; the nasal process of the premaxilla being less exposed on the dorsal surface of the skull than those in other known oviraptorids; the length of the frontal being approximately one fourth that of the parietal along the midline of the skull. Phylogenetic analysis shows that Nemegtia barsboldi is more closely related to Citipati osmolskae than to any other oviraptorosaurs. Key words : Nemegt Basin, Mongolia, Nemegt Formation, Late Cretaceous, Oviraptorosauria, Nemegtia. dae, and Caudipterygidae (Barsbold, 1976; Stern- Introduction berg, 1940; Currie, 2000; Clark et al., 2001; Ji et Oviraptorosaurs are generally regarded as non- al., 1998; Zhou and Wang, 2000; Zhou et al., avian theropod dinosaurs (Osborn, 1924; Bars- 2000). -

Avian Tail Ontogeny, Pygostyle Formation, and Interpretation of Juvenile Mesozoic Specimens Dana J

Clemson University TigerPrints Publications Biological Sciences 6-13-2018 Avian tail ontogeny, pygostyle formation, and interpretation of juvenile Mesozoic specimens Dana J. Rashid Montana State University-Bozeman Kevin Surya Montana State University-Bozeman Luis M. Chiappe Dinosaur Institute, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History Nathan Carroll Dinosaur Institute, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History Kimball L. Garrett Section of Ornithology, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/bio_pubs Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Please use the publisher's recommended citation. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-27336-x#rightslink This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Dana J. Rashid, Kevin Surya, Luis M. Chiappe, Nathan Carroll, Kimball L. Garrett, Bino Varghese, Alida Bailleul, Jingmai K. O'Connor, Susan C. Chapman, and John R. Horner This article is available at TigerPrints: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/bio_pubs/112 www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Avian tail ontogeny, pygostyle formation, and interpretation of juvenile Mesozoic specimens Received: 27 March 2018 Dana J. Rashid1, Kevin Surya2, Luis M. Chiappe3, Nathan Carroll3, Kimball L. Garrett4, Bino Accepted: 23 May 2018 Varghese5, Alida Bailleul6,7, Jingmai K. O’Connor 7, Susan C. Chapman 8 & John R. Horner1,9 Published: xx xx xxxx The avian tail played a critical role in the evolutionary transition from long- to short-tailed birds, yet its ontogeny in extant birds has largely been ignored. -

Magnificent Magpie Colours by Feathers with Layers of Hollow Melanosomes Doekele G

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb174656. doi:10.1242/jeb.174656 RESEARCH ARTICLE Magnificent magpie colours by feathers with layers of hollow melanosomes Doekele G. Stavenga1,*, Hein L. Leertouwer1 and Bodo D. Wilts2 ABSTRACT absorption coefficient throughout the visible wavelength range, The blue secondary and purple-to-green tail feathers of magpies are resulting in a higher refractive index (RI) than that of the structurally coloured owing to stacks of hollow, air-containing surrounding keratin. By arranging melanosomes in the feather melanosomes embedded in the keratin matrix of the barbules. barbules in more or less regular patterns with nanosized dimensions, We investigated the spectral and spatial reflection characteristics of vivid iridescent colours are created due to constructive interference the feathers by applying (micro)spectrophotometry and imaging in a restricted wavelength range (Durrer, 1977; Prum, 2006). scatterometry. To interpret the spectral data, we performed optical The melanosomes come in many different shapes and forms, and modelling, applying the finite-difference time domain (FDTD) method their spatial arrangement is similarly diverse (Prum, 2006). This has as well as an effective media approach, treating the melanosome been shown in impressive detail by Durrer (1977), who performed stacks as multi-layers with effective refractive indices dependent on extensive transmission electron microscopy of the feather barbules the component media. The differently coloured magpie feathers are of numerous bird species. He interpreted the observed structural realised by adjusting the melanosome size, with the diameter of the colours to be created by regularly ordered melanosome stacks acting melanosomes as well as their hollowness being the most sensitive as optical multi-layers. -

The Molecular Evolution of Feathers with Direct Evidence from Fossils

The molecular evolution of feathers with direct evidence from fossils Yanhong Pana,1, Wenxia Zhengb, Roger H. Sawyerc, Michael W. Penningtond, Xiaoting Zhenge,f, Xiaoli Wange,f, Min Wangg,h, Liang Hua,i, Jingmai O’Connorg,h, Tao Zhaoa, Zhiheng Lig,h, Elena R. Schroeterb, Feixiang Wug,h, Xing Xug,h, Zhonghe Zhoug,h,i,1, and Mary H. Schweitzerb,j,1 aChinese Academy of Sciences Key Laboratory of Economic Stratigraphy and Palaeogeography, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology and Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; bDepartment of Biological Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695; cDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29205; dAmbioPharm Incorporated, North Augusta, SC 29842; eInstitute of Geology and Paleontology, Lingyi University, Lingyi City, 27605 Shandong, China; fShandong Tianyu Museum of Nature, Pingyi, 273300 Shandong, China; gCAS Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100044 Beijing, China; hCenter for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100044 Beijing, China; iCollege of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100049 Beijing, China; and jNorth Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh, NC 27601 Contributed by Zhonghe Zhou, December 15, 2018 (sent for review September 12, 2018; reviewed by Dominique G. Homberger and Chenxi Jia) Dinosaur fossils possessing integumentary appendages of various feathers in Anchiornis, barbules that interlock to form feather morphologies, interpreted as feathers, have greatly enhanced our vanes critical for flight have not been identified yet (12). -

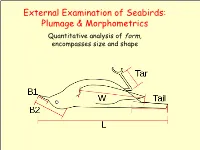

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics Quantitative analysis of form, encompasses size and shape Seabird Topography ➢ Naming Conventions: • Parts of the body • Types of feathers (Harrison 1983) Types of Feathers Coverts: Rows bordering and overlaying the edges of the tail and wings on both the lower and upper sides of the body. Help streamline shape of the wings and tail and provide the bird with insulation. Feather Tracks ➢ Feathers are not attached randomly. • They occur in linear tracts called pterylae. • Spaces on bird's body without feather tracts are called apteria. • Densest area for feather tracks is head and neck. • Feathers arranged in distinct layers: contour feathers overlay down. Generic Pterylae Types of Feathers Contour feathers: outermost feathers. Define the color and shape of the bird. Contour feathers lie on top of each other, like shingles on a roof. Shed water, keeping body dry and insulated. Each contour feather controlled by specialized muscles which control their position, allowing the bird to keep the feathers in clean and neat condition. Specialized contour feathers used for flight: delineate outline of wings and tail. Types of Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Define outline of wings and tail Long and stiff Asymmetrical those on wings are called remiges (singular remex) those on tail are called retrices (singular retrix) Types of Flight Feathers Remiges: Largest contour feathers (primaries / secondaries) Responsible for supporting bird during flight. Attached by ligaments or directly to the wing bone. Types of Flight Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Rectrices: tail feathers provide flight stability and control. Connected to each other by ligaments, with only the inner- most feathers attached to bone. -

Avian Tail Ontogeny, Pygostyle Formation, and Interpretation of Juvenile Mesozoic Specimens Received: 27 March 2018 Dana J

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Avian tail ontogeny, pygostyle formation, and interpretation of juvenile Mesozoic specimens Received: 27 March 2018 Dana J. Rashid1, Kevin Surya2, Luis M. Chiappe3, Nathan Carroll3, Kimball L. Garrett4, Bino Accepted: 23 May 2018 Varghese5, Alida Bailleul6,7, Jingmai K. O’Connor 7, Susan C. Chapman 8 & John R. Horner1,9 Published: xx xx xxxx The avian tail played a critical role in the evolutionary transition from long- to short-tailed birds, yet its ontogeny in extant birds has largely been ignored. This defcit has hampered eforts to efectively identify intermediate species during the Mesozoic transition to short tails. Here we show that fusion of distal vertebrae into the pygostyle structure does not occur in extant birds until near skeletal maturity, and mineralization of vertebral processes also occurs long after hatching. Evidence for post-hatching pygostyle formation is also demonstrated in two Cretaceous specimens, a juvenile enantiornithine and a subadult basal ornithuromorph. These fndings call for reinterpretations of Zhongornis haoae, a Cretaceous bird hypothesized to be an intermediate in the long- to short-tailed bird transition, and of the recently discovered coelurosaur tail embedded in amber. Zhongornis, as a juvenile, may not yet have formed a pygostyle, and the amber-embedded tail specimen is reinterpreted as possibly avian. Analyses of relative pygostyle lengths in extant and Cretaceous birds suggests the number of vertebrae incorporated into the pygostyle has varied considerably, further complicating the interpretation of potential transitional species. In addition, this analysis of avian tail development reveals the generation and loss of intervertebral discs in the pygostyle, vertebral bodies derived from diferent kinds of cartilage, and alternative modes of caudal vertebral process morphogenesis in birds. -

Insight Into the Evolution of Avian Flight from a New Clade of Early

J. Anat. (2006) 208, pp287–308 IBlackwnell Publishing sLtd ight into the evolution of avian flight from a new clade of Early Cretaceous ornithurines from China and the morphology of Yixianornis grabaui Julia A. Clarke,1 Zhonghe Zhou2 and Fucheng Zhang2 1Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA 2Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Abstract In studies of the evolution of avian flight there has been a singular preoccupation with unravelling its origin. By con- trast, the complex changes in morphology that occurred between the earliest form of avian flapping flight and the emergence of the flight capabilities of extant birds remain comparatively little explored. Any such work has been limited by a comparative paucity of fossils illuminating bird evolution near the origin of the clade of extant (i.e. ‘modern’) birds (Aves). Here we recognize three species from the Early Cretaceous of China as comprising a new lineage of basal ornithurine birds. Ornithurae is a clade that includes, approximately, comparatively close relatives of crown clade Aves (extant birds) and that crown clade. The morphology of the best-preserved specimen from this newly recognized Asian diversity, the holotype specimen of Yixianornis grabaui Zhou and Zhang 2001, complete with finely preserved wing and tail feather impressions, is used to illustrate the new insights offered by recognition of this lineage. Hypotheses of avian morphological evolution and specifically proposed patterns of change in different avian locomotor modules after the origin of flight are impacted by recognition of the new lineage.