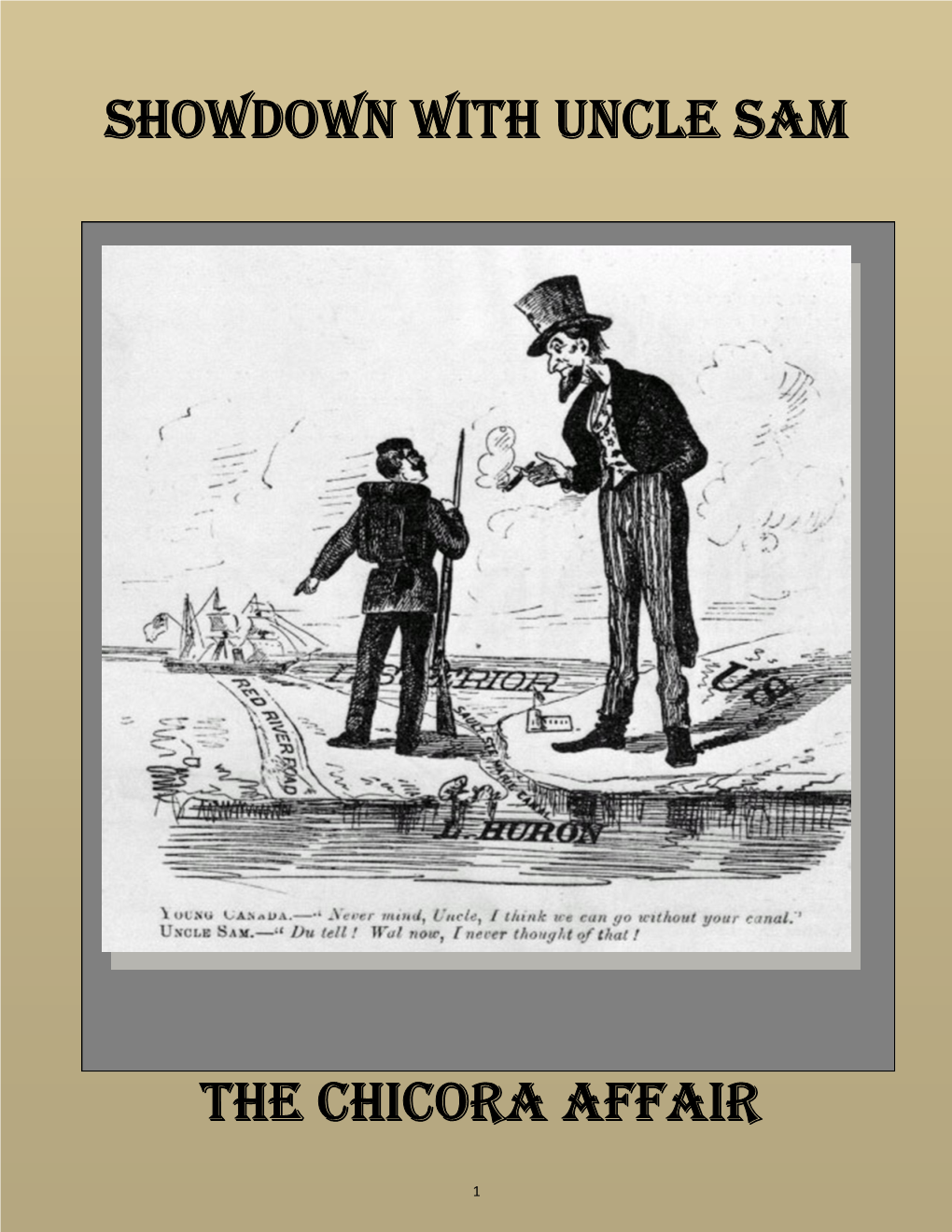

Showdown with Uncle Sam the Chicora Affair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francis I. W. Jones Treason and Piracy in Civil War Halifax: the Second Chesapeake Affair Revisited "A Terrible Retribution

Francis I. W. Jones Treason And Piracy In Civil War Halifax: The Second Chesapeake Affair Revisited "A terrible retribution awaits the city of Halifax for its complicity in treason and piracy." From the diary of Rev. N. Gunnison Reverend Nathaniel Gunnison, American Consul at Halifax, wrote to Sir Charles Tupper, provincial secretary of Nova Scotia, 10 December 1863, stating that the Chesapeake "had been seized by a band of pirates and murder committed" (Doyle to Newcastle 23 Dec. 1863; Lieut. Governor's Correspondence, RG 1). 1 The Chesapeake was an American steamer plying between New York and Portland, Maine, which had been captured by a party of sixteen men, led by John C. Braine, who had embarked as passengers at New York. After a foray into the Bay of Fundy and along the south shore of Nova Scotia, the Chesapeake was boarded and captured by a United States gunboat the Ella and Annie in Sambro Harbor fourteen miles from Halifax. She was subsequently towed into Halifax and turned over to local authorities after much diplomatic burly burly (Admiralty Papers 777). The affair raised several interesting points of international maritime law, resulted in three trials before the issues raised by the steamer's seizure, recapture and disposition were resolved and was the genesis of several myths and local legends. It not only provided Halifax with "the most exciting Christmas Week in her history" TREASON AND PIRACY IN CIVIL WAR HALIFAX 473 (McDonald 602), it posed the "most thorny diplomatic problem of the Civil War" (Overholtzer 34)? The story of the capture and recapture of the Chesapeake has been told several times with varying degrees of accuracy. -

The Chesapeake Affair Nick Mann

58 Western Illinois Historical Review © 2011 Vol. III, Spring 2011 ISSN 2153-1714 Sailors Board Me Now: The Chesapeake Affair Nick Mann In exploring the origins of the War of 1812, many historians view the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe as the final breaking point in diplomatic relations between the United States and Great Britain. While the clash at Tippecanoe was a serious blow to peace between the two nations, Anglo-American relations had already been ruptured well before the presidency of James Madison. Indian affairs certainly played a role in starting the war, but it was at sea where the core problems lay. I will argue in this essay that rather than the Battle of Tippecanoe, it was the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair of 1807 that set Great Britain and the United States on the path towards war. The affair signified two of the festering issues facing the British and Americans: impressment and neutral rights. Though President Jefferson was able to prevent war in 1807, his administration‟s inept diplomacy widened the existing gap between Britain and America. On both sides of the Atlantic, the inability of leaders such as Secretary of State Madison and the British foreign minister, George Canning to resolve the affair poisoned diplomatic relations for years afterward. To understand the origin of the War of 1812, one must consider how the Chesapeake affair deteriorated Anglo-American relations to a degree that the Battle of Tippecanoe was less important that some have imagined. The clash at Tippecanoe between Governor William Henry Harrison and the forces of the Shawnee Prophet has usually been seen as the direct catalyst for the war in much of the historiography dealing with the War of 1812. -

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR and the BRITISH IMPERIAL DILEMMA TREVOR COX a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR AND THE BRITISH IMPERIAL DILEMMA TREVOR COX A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2015 This work or any part thereof has not been presented in any form to the University or to any other body whether for the purposes of assessment, publication or for any other purpose (unless otherwise indicated). Save for any express acknowledgements, references and/or bibliographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and of no other person. The right of Trevor Cox to be identified as author of this work is asserted in accordance with ss. 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. At this date is copyright is owned by the author. Signature ................................................... Date ............................................................ 1 ABSTACT The following study argues that existing historical interpretations of how and why the unification of British North America came about in 1867are flawed. It contends that rather than a movement propelled mainly by colonial politicians in response to domestic pressures - as generally portrayed in Canadian-centric histories of Confederation - the imperial government in Britain actually played a more active and dynamic role due to the strategic and political pressures arising from the American Civil War. Rather than this being a basic ‘withdrawal’, or ‘abandonment’ in the face of US power as is argued on the rare occasions diplomatic or strategic studies touch upon the British North American Act: this thesis argues that the imperial motivations were more far-reaching and complex. -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS Tony Tanner (ed.). The Oxford Book of Sea Allan Poe's "Descent into the Maelstrom," and Stories. New York & Toronto: Oxford Univer• H.G. Wells' "In the Abyss," imagine the terrors sity Press, 1994. xviii + 410 pp. $36.95, cloth; and mysteries of the sea in tales of supernatural ISBN 0-19-214210-0. moment. E.M. Forster's "The Story of the Siren" and Malcom Lowry's "The Bravest Boat" The sea assumes a timeless presence in this present a gentle contrast to these adventures collection of fiction from Oxford. Tony Tanner through their writers' rendering of lives attuned has selected a diverse assortment of stories by to the sea's rhythms. But the true gems in the well-known British, American and Canadian book, possibly the best ever written in the genre, writers. Through his editing, he emphasizes the Conrad's "The Secret Sharer" and Stephen eternal quality of the tales at the expense of Crane's "The Open Boat," bridge these two historical and social contexts, presenting stories forms, focusing in lyrical fashion on their involving sailors and landlubbers alike. The narrators' moral dilemmas within the intrigue of selections are arranged roughly chronologically, the adventure plots. encompassing the period from 1820 to 1967, As this list indicates, Tanner has selected and amply representing Great Britain (fifteen tales that will appeal to romantics and realists stories) and the United States (eleven stories). alike, but his interest is clearly aesthetic, not Canada gets short shrift, with only Charles G.D. historical. His muse in this regard seems to be Roberts, an odd choice, represented. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

North Atlantic Press Gangs: Impressment and Naval-Civilian Relations in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, 1749-1815 by Keith Mercer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2008 © Copyright by Keith Mercer, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Few Americans in the 1790S Would Have Predicted That the Subject Of

AMERICAN NAVAL POLICY IN AN AGE OF ATLANTIC WARFARE: A CONSENSUS BROKEN AND REFORGED, 1783-1816 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jeffrey J. Seiken, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor John Guilmartin, Jr., Advisor Professor Margaret Newell _______________________ Professor Mark Grimsley Advisor History Graduate Program ABSTRACT In the 1780s, there was broad agreement among American revolutionaries like Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton about the need for a strong national navy. This consensus, however, collapsed as a result of the partisan strife of the 1790s. The Federalist Party embraced the strategic rationale laid out by naval boosters in the previous decade, namely that only a powerful, seagoing battle fleet offered a viable means of defending the nation's vulnerable ports and harbors. Federalists also believed a navy was necessary to protect America's burgeoning trade with overseas markets. Republicans did not dispute the desirability of the Federalist goals, but they disagreed sharply with their political opponents about the wisdom of depending on a navy to achieve these ends. In place of a navy, the Republicans with Jefferson and Madison at the lead championed an altogether different prescription for national security and commercial growth: economic coercion. The Federalists won most of the legislative confrontations of the 1790s. But their very success contributed to the party's decisive defeat in the election of 1800 and the abandonment of their plans to create a strong blue water navy. -

Guide to Canadian Sources Related to Southern Revolutionary War

Research Project for Southern Revolutionary War National Parks National Parks Service Solicitation Number: 500010388 GUIDE TO CANADIAN SOURCES RELATED TO SOUTHERN REVOLUTIONARY WAR NATIONAL PARKS by Donald E. Graves Ensign Heritage Consulting PO Box 282 Carleton Place, Ontario Canada, K7C 3P4 in conjunction with REEP INC. PO Box 2524 Leesburg, VA 20177 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1: INTRODUCTION AND GUIDE TO CONTENTS OF STUDY 1A: Object of Study 1 1B: Summary of Survey of Relevant Primary Sources in Canada 1 1C: Expanding the Scope of the Study 3 1D: Criteria for the Inclusion of Material 3 1E: Special Interest Groups (1): The Southern Loyalists 4 1F: Special Interest Groups (2): Native Americans 7 1G: Special Interest Groups (3): African-American Loyalists 7 1H: Special Interest Groups (4): Women Loyalists 8 1I: Military Units that Fought in the South 9 1J: A Guide to the Component Parts of this Study 9 PART 2: SURVEY OF ARCHIVAL SOURCES IN CANADA Introduction 11 Ontario Queen's University Archives, Kingston 11 University of Western Ontario, London 11 National Archives of Canada, Ottawa 11 National Library of Canada, Ottawa 27 Archives of Ontario, Toronto 28 Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library 29 Quebec Archives Nationales de Quebec, Montreal 30 McCord Museum / McGill University Archives, Montreal 30 Archives de l'Universite de Montreal 30 New Brunswick 32 Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, Fredericton 32 Harriet Irving Memorial Library, Fredericton 32 University of New Brunswick Archives, Fredericton 32 New Brunswick Museum Archives, -

The Impact of the Civil War on Canada

Mahpiya Vanderbilt ¨ Canadian opinion reflected Britain’s view which leaned towards South ¨ Both Britain and Canada were officially neutral ¨ Washington was hostile to Britain and British North America ¨ Britain and Canada feared attack on Canada by Union forces ¡ Thought the Union would seek Canada as new territory ¨ People felt that the colonies cost too much to maintain ¡ the cost of protective trade tariffs ¡ the cost of maintaining the apparatus of political control ¨ Colonies began to approach England about independence and confederation ¡ England was willing give up political hold on the colonies ¡ Intended to keep as much economic control as possible ¨ British North America ¨ British Controlled Colonies ¡ United Province of Canada ¡ Newfoundland ¡ The Maritimes ú New Brunswick ú Prince Edward Island ú Nova Scotia ¡ Rupert’s Land ¨ Slavery ban in Canada was official by 1833 ¨ Underground Railroad ¡ An informal network of safe houses and people ¡ Helped fugitive slaves travel from slave states in the US to free states or Canada ¡ Perhaps 30,000 slaves reached Canada ¡ Operated c. 1840-60 ¡ was most effective after the passage of the US Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 ú Resulted in several efforts to kidnap fugitives who were in Canada to return them to Southern owners ¨ Used Canada as a base ¨ Wanted to start a war between Canada and The Union ¨ Many Confederates hid in Canada ¨ One man had orders from the Confederate War Department ¡ for "detailed for special service” in Canada and was empowered to carry out “any hostile operation” that -

Jeffersonianism and 19Th Century American Maritime Defense Policy. Christopher Taylor Ziegler East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2003 Jeffersonianism and 19th Century American Maritime Defense Policy. Christopher Taylor Ziegler East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Ziegler, Christopher Taylor, "Jeffersonianism and 19th Century American Maritime Defense Policy." (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 840. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/840 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jeffersonianism and 19th Century American Maritime Defense Policy A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History By Christopher T. Ziegler December 2003 Dale Royalty Ronnie Day Dale Schmitt Keywords: Thomas Jefferson, Jeffersonianism, Maritime Defense, Navy, Coastal Defense, Embargo, Non-importation ABSTRACT Jeffersonianism and 19th Century American Maritime Defense Policy By Christopher T. Ziegler This paper analyzes the fundamental maritime defense mentality that permeated America throughout the early part of the Republic. For fear of economic debt and foreign wars, Thomas Jefferson and his Republican party opposed the construction of a formidable blue water naval force. Instead, they argued for a small naval force capable of engaging the Barbary pirates and other small similar forces. -

Course Title History 1301 - 61009 Fall Semester, 2017 8/21/1917-12/7/2017

COURSE TITLE HISTORY 1301 - 61009 FALL SEMESTER, 2017 8/21/1917-12/7/2017 Professor: Richard L. Means Office: W-193-B Phone: (214) 860-8724 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday – 10:30-12:30 Tuesday – 8:00-9:30 & 1:50-2:50 Wednesday – 10:00-12:30 Thursday – 8:00-9:30 Class Meeting Time and Room: T TH – 9:30-10:50- W168 3 Credit Hours Division of Communications and Social Science – Phone: (214) 860-8830 –W279B Course Description: This is a general survey of United States history from the Age of Discovery to the year 1877. Prerequisites: One of the following must be met. 1. Developmental Reading 0093 and Developmental Writing 0093; 2. English as a Second Language (ESOL) 0044 and 0054; or have met the Texas Success Initiative (TSI) in Reading and Writing Standards and DCCCD Writing score prerequisite requirement. Required Course Materials: Required Textbook: Goldfield, Abbot, et.al., The American Journey: A History of the United States, Volume 1, 8th Edition, ISBN# 9780134102924 Supplemental Required Books: You will be required to read any TWO of the following books: Deborah Gray White, Ar'n't I a Woman: Female Slaves in the Plantation South, Norton Publishers, ISBN# 0-393-31481-2 Randolph B. Campbell, Sam Houston and the American Southwest, Longman Publishers, ISBN# 0-321- 09139-6 Charles W. Akers, Abigail Adams: An American Woman, Longman Publishers, ISBN# 0-321-04370-7 R. David Edmunds, Tecumseh and the Quest for Indian Leadership, Longman Publishers, ISBN#O-673- 39336-4 STATE REQUIREMENTS: Core Curriculum Objectives: 1. -

The War of 1812

The War of 1812 In St. Thomas and Elgin County Cover a The War of 1812 in St. Thomas and Elgin County -The Preliminaries to War- The War of 1812 was a conflict between Great Britain and the United States. It evolved from the Napoleonic Wars in which Great Britain and France vied for naval supremacy. In 1806, Napoleon issued the Berlin Decree which ordered all ports under his control to be closed to British ships and demanded that all neutral and French ships would be seized if they entered a British port en route to a continental port. The British retaliated with Orders-in-Council which stipulated that all neutral ships obtain a licence before sailing to Europe. The British began to stop and search American ships for contraband and to press American citizens into service on the British ships. The culmination of these tactics was the Chesapeake Affair. In 1807, several British sailors deserted their ship the HMS Leopard that was patrolling along the shore of Chesapeake Bay between Maryland and Virginia. They enlisted in the American navy on an American ship also named the Chesapeake that was in the area. When the British ship the Leopard attempted to board and search the Chesapeake, consent was refused. The Leopard opened fire, killing three and injuring eighteen of the Chesapeake’s crew. The dispute over maritime rights might have been settled by diplomacy except for interests in the United States that advocated war. Major General Dearborn had presented President Madison with an analysis that in the event of war, Upper and Lower Canada would be easily overtaken and indeed such an invasion would be welcome by the settlers. -

Recent Publications Relating to the History of the Atlantic Region Elizabeth W

Document generated on 09/26/2021 6:42 a.m. Acadiensis Recent Publications Relating to the History of the Atlantic Region Elizabeth W. McGahan, Joan Ritcey, John MacLeod and Frank L. Pigot Volume 22, Number 2, Spring 1993 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/acad22_2bib01 See table of contents Publisher(s) The Department of History of the University of New Brunswick ISSN 0044-5851 (print) 1712-7432 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document McGahan, E. W., Ritcey, J., MacLeod, J. & Pigot, F. L. (1993). Recent Publications Relating to the History of the Atlantic Region. Acadiensis, 22(2), 186–206. All rights reserved © Department of History at the University of New This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Brunswick, 1993 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 186 Acadiensis Recent Publications Relating to the History of the Atlantic Region Editor: Elizabeth W. McGahan, Contributors: Joan Ritcey, New Brunswick. Newfoundland and Labrador. John MacLeod, Nova Scotia. Frank L. Pigot, Prince Edward Island. ATLANTIC PROVINCES (This material considers two or more of the Atlantic Provinces.) Abucar, Mohamed Hagi. Italians. Tantallon, N.S.: Four East, 1991. Bannister, Ralph K. Orthodoxy and the theory of fishery management: the policy and practice of fishery management theory past and present.