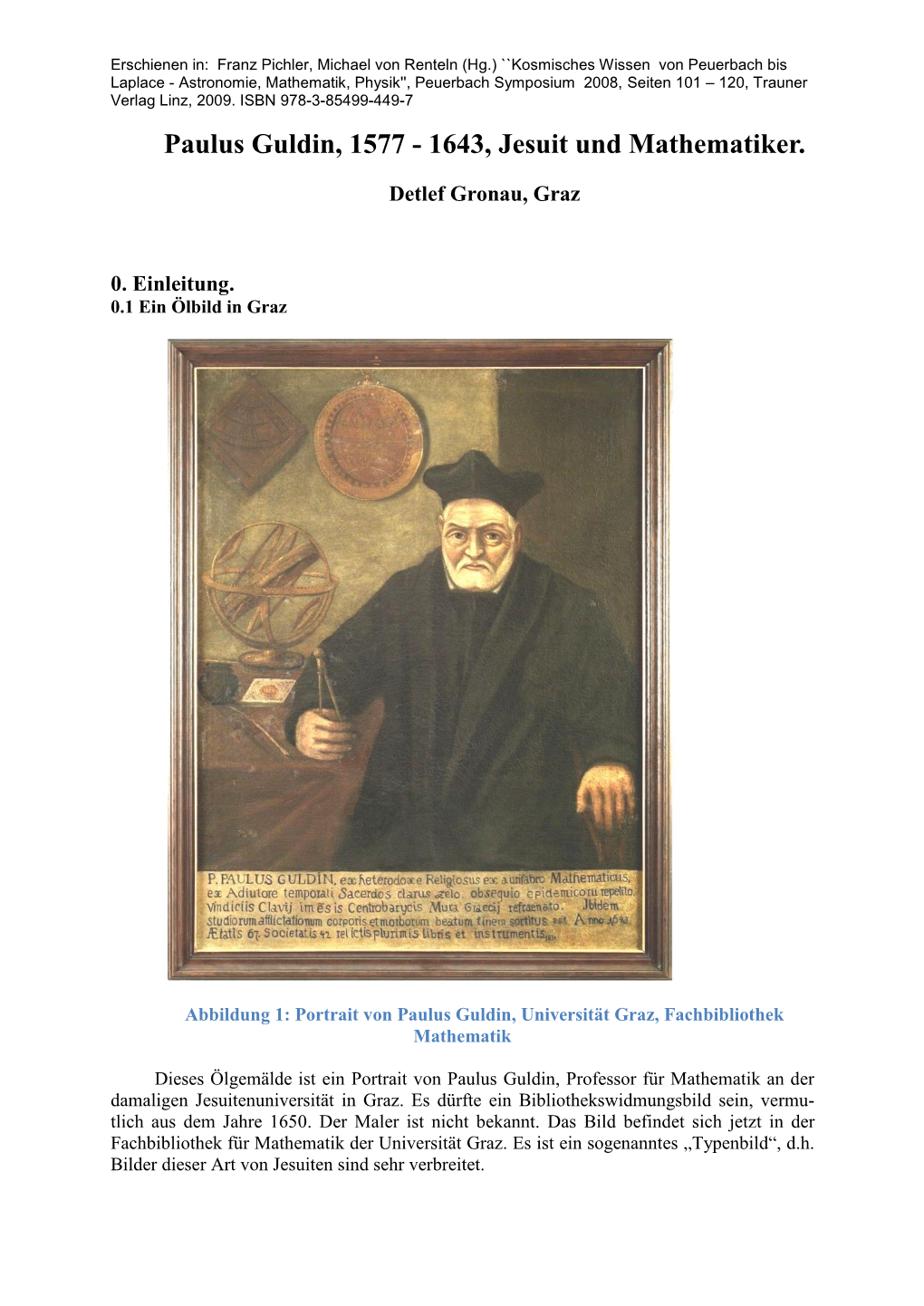

Paulus Guldin, 1577 - 1643, Jesuit Und Mathematiker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kepler's Cosmological Synthesis

Kepler’s Cosmological Synthesis History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 39 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J. M. M. H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C. H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 20 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Kepler’s Cosmological Synthesis Astrology, Mechanism and the Soul By Patrick J. Boner LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Kepler’s Supernova, SN 1604, appears as a new star in the foot of Ophiuchus near the letter N. In: Johannes Kepler, De stella nova in pede Serpentarii, Prague: Paul Sessius, 1606, pp. 76–77. Courtesy of the Department of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Milton S. Eisenhower Library, Johns Hopkins University. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Boner, Patrick, author. Kepler’s cosmological synthesis: astrology, mechanism and the soul / by Patrick J. Boner. pages cm. — (History of science and medicine library, ISSN 1872-0684; volume 39; Medieval and early modern science; volume 20) Based on the author’s doctoral dissertation, University of Cambridge, 2007. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-24608-9 (hardback: alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-24609-6 (e-book) 1. Kepler, Johannes, 1571–1630—Philosophy. 2. Cosmology—History. 3. Astronomy—History. I. Title. II. Series: History of science and medicine library; v. 39. III. Series: History of science and medicine library. Medieval and early modern science; v. 20. QB36.K4.B638 2013 523.1092—dc23 2013013707 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 Si Tantus Amor Belli Tibi, Roma, Nefandi. Love and Strife in Lucan's Bellum Civile Giulio Celotto Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES SI TANTUS AMOR BELLI TIBI, ROMA, NEFANDI. LOVE AND STRIFE IN LUCAN’S BELLUM CIVILE By GIULIO CELOTTO A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Giulio Celotto defended this dissertation on February 28, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Tim Stover Professor Directing Dissertation David Levenson University Representative Laurel Fulkerson Committee Member Francis Cairns Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above5na ed co ittee e bers, and certifies that the dissertation has been appro0ed in accordance 1ith uni0ersity require ents. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The co pletion of this dissertation could not ha0e been possible 1ithout the help and the participation of a nu ber of people. It is a great pleasure to be able to ac3no1ledge the here. I a ost grateful to y super0isor, Professor Ti Sto0er, for his guidance and dedication throughout the entire ti e of y research. I 1ish to e6tend y than3s to the other Co ittee e bers, Professors Laurel Ful3erson, Francis Cairns, and Da0id Le0enson, for their ad0ice at e0ery stage of y research. I 1ould li3e to e6press y deepest gratitude to Professor Andre1 7issos, 1ho read the entire anuscript at a later stage, and offered any helpful suggestions and criticis s. -

The Watershed: a Biography of Johannes Kepler

The Watershed By Arthur Koestler Spanish Tertament Gladiators Darkness at Noon Scum of the Earth Arrival andDeparture The Yogi and the Commissar Twilight Bctr Thieves in the Night Insight andOutlook The Structure of a Miracle Age of Longing Promise and Fulfillment .Arrow in the Blue The InvisibleWriting Trail of the Dinosaur Reflections on Hanging The Sleepwolkers ARTHUR KoESTLER, born in Budapest in 1905 and edu cated in Viemia, began his writing career as an editor of a German and Arabian weekly newspaper in Cairo. This led to his becoming the Near East correspondent for the Ullstein newspapers of Berlin. Future assign ments included the Graf Zepplin's flight over the Arctic in 1931 and the Civil War in Spain, where he was im prisoned, sentenced to death, and finally pardoned by the rebels. An active communist from 1931 to 1938, Koestler achieved world fame with DARKNESS AT NooN ( 1941), his explosive anti-communist novel. He now lives in England. A more comprehensive biography ap pears in John Durston's Foreword. THE WATERSHED A Biography of Johannes Kepler .Arthur Koestler Foreword by John Durston ILLUSTRATED BY R. PAUL LARKIN Published by Anchor Books Doubleday & Company, Inc. Garden City, New York LibrtJT)' of Congress Catalog Card Number 6o-13537 Copyright© 1960 by EducatiorudServices Incorporated From THE SLEEPWALKERS © Arthur Koestler 1959 by prmnjssion of the author and The Macmillan Company, New York and Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd. All Rights Reserved Printed in the United Statesof Americtt THE SCIENCE STUDY SERIES The Science Study Series offers to students and to the general public the writing of distinguished authors on the most stirring and fundamental topics of physics, from the smallest known particles to the whole universe. -

By Christopher Reed

Gingerich.final 10/6/03 7:07 PM Page 44 The Copernicus Quest How an astrophysicist with a “collecting gene” became the world’s authority on a revolutionary, allegedly unread book by Christopher Reed wen gingerich, ph.d. ’62, takes a seat revoluty-own-ibus” is a good approximation of its proper pro- on his “rocket cart”—a dolly with a steer- nunciation, says Gingerich. Its title page reminds him of an op- ing stick in front, a straight-backed chair tometrist’s chart: amidship, and a big fire-extinguisher NICOLAUS CO mounted at back. Donning a crash helmet PERNICUS OF TORUN and an aviator’s scarf for the trip, he reaches about the revolutions of behind him and turns on the extinguisher, the Heavenly Spheres in Six Books. which releases a propulsive jet of carbon dioxide. The cart begins to move across the floor of the Science Copernicus argued against the conventional wisdom, promul- Center lecture hall. Gingerich picks up speed until he is accelerat- gated by Claudius Ptolemy in Alexandria around a.d. 150, that ing furiously with a look of terror on his face toward a side door, the earth was fixed at the middle of the universe. He proposed which flies open just in time and out he goes. Assistants in the instead that what could be observed of planetary motion could wings drop “a big sack full of pipes,” he explains, which make a be explained if the sun was immovable in the middle, with the huge clatter o≠ stage. Gingerich is demonstrating Newton’s third earth and other planets going around it, the modern understand- Olaw, that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. -

Fermat's Dilemma: Why Did He Keep Mum on Infinitesimals? and The

FERMAT’S DILEMMA: WHY DID HE KEEP MUM ON INFINITESIMALS? AND THE EUROPEAN THEOLOGICAL CONTEXT JACQUES BAIR, MIKHAIL G. KATZ, AND DAVID SHERRY Abstract. The first half of the 17th century was a time of in- tellectual ferment when wars of natural philosophy were echoes of religious wars, as we illustrate by a case study of an apparently innocuous mathematical technique called adequality pioneered by the honorable judge Pierre de Fermat, its relation to indivisibles, as well as to other hocus-pocus. Andr´eWeil noted that simple appli- cations of adequality involving polynomials can be treated purely algebraically but more general problems like the cycloid curve can- not be so treated and involve additional tools–leading the mathe- matician Fermat potentially into troubled waters. Breger attacks Tannery for tampering with Fermat’s manuscript but it is Breger who tampers with Fermat’s procedure by moving all terms to the left-hand side so as to accord better with Breger’s own interpreta- tion emphasizing the double root idea. We provide modern proxies for Fermat’s procedures in terms of relations of infinite proximity as well as the standard part function. Keywords: adequality; atomism; cycloid; hylomorphism; indi- visibles; infinitesimal; jesuat; jesuit; Edict of Nantes; Council of Trent 13.2 Contents arXiv:1801.00427v1 [math.HO] 1 Jan 2018 1. Introduction 3 1.1. A re-evaluation 4 1.2. Procedures versus ontology 5 1.3. Adequality and the cycloid curve 5 1.4. Weil’s thesis 6 1.5. Reception by Huygens 8 1.6. Our thesis 9 1.7. Modern proxies 10 1.8. -

Cavalieri's Method of Indivisibles

Cavalieri's Method of Indivisibles KIRSTI ANDERSEN Communicated by C. J. SCRIBA & OLAF PEDERSEN BONAVENTURA CAVALIERI(Archivio Fotografico dei Civici Musei, Milano) 292 K. ANDERSEN Contents Introduction ............................... 292 I. The Life and Work of Cavalieri .................... 293 II. Figures .............................. 296 III. "All the lines" . .......................... 300 IV. Other omnes-concepts ........................ 312 V. The foundation of Cavalieri's collective method of indivisibles ...... 315 VI. The basic theorems of Book II of Geometria .............. 321 VII. Application of the theory to conic sections ............... 330 VIII. Generalizations of the omnes-concept ................. 335 IX. The distributive method ....................... 348 X. Reaction to Cavalieri's method and understanding of it ......... 353 Concluding remarks ........................... 363 Acknowledgements ............................ 364 List of symbols ............................. 364 Literature ................................ 365 Introduction CAVALIERI is well known for the method of indivisibles which he created during the third decade of the 17 th century. The ideas underlying this method, however, are generally little known.' This almost paradoxical situation is mainly caused by the fact that authors dealing with the general development of analysis in the 17 th century take CAVALIERI as a natural starting point, but do not discuss his rather special method in detail, because their aim is to trace ideas about infinites- imals. There has even been a tendency to present the foundation of his method in a way which is too simplified to reflect CAVALIERI'S original intentions. The rather vast literature, mainly in Italian, explicitly devoted to CAVALIERI does not add much to a general understanding of CAVALIERI'Smethod of indivi- sibles, because most of these studies either presuppose a knowledge of the method or treat specific aspects of it. -

How a Dangerous Mathematical Theory Shaped the Modern World

it. As Clavius points out in the “Prolegomena,” it was the sturdiest edifice in the kingdom of knowledge. For a taste of the Euclidean method, consider Euclid’s proof of proposition 32 in book 1: that the sum of the angles of any triangle is equal to two right angles—or, as we would say, 180 degrees. Euclid, at this point, has already proven that when a straight line falls on two parallel lines, it creates the same angles with one parallel line as with the other (book 1, proposition 29). He makes good use of this theorem here: Proposition 32: In any triangle, if one of the sides be produced, the exterior angle is equal to the two interior and opposite angles, and the three interior angles of the triangle are equal to two right angles. Proof: Let ABC be a triangle and let one side of it be produced to D. I say that the exterior angle ACD is equal to the two interior and opposite angles CAB, ABC, and the three interior angles of the triangle, ABC, BCA, CAB, are equal to two right angles. Figure 2.1. The sum of the angles in a triangle. 92 This was Salviati’s (Galileo’s) theory of matter, and as he himself admitted, it was a difficult one. “What a sea we are slipping into without knowing it!” Salviati exclaims at one point. “With vacua, and infinities, and indivisibles … shall we ever be able, even by means of a thousand discussions, to reach dry land?” Indeed, can a finite amount of material be composed of an infinite number of atoms and an infinite number of empty spaces? To prove his point that it could, he turned to mathematics. -

Kepler's "War on Mars" and the Usurpation of Seventeenth-Century Astronomy

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Dorsey, William Anthony Robert (2012) Kepler's "War on Mars" and the usurpation of seventeenth-century astronomy. Professional Doctorate (Research) thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/29931/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/29931/ 1 Kepler‟s “War on Mars” and the Usurpation of Seventeenth-Century Astronomy Thesis submitted by William Anthony Robert DORSEY, B.A. (New School University), Master of Astronomy (University of Western Sydney) in September 2012 for the degree of Doctor of Astronomy in the School of Engineering and Physical Sciences James Cook University 2 STATEMENT OF ACCESS I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and, via the Australian Digital Thesis network, for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and; I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. Signature Date 12-06-2012 3 STATEMENT OF SOURCES DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. -

Principal Manuscript Sources Consulted Florence: Archivio Di

Principal manuscript sources consulted Florence: Archivio di Stato Carte Bardi, Serie II. 43, Anon., Filza miscellanea di memorie, studi, disegni di Astronomia, Architettura militare, Fortificazione etc, 17th century. Carte Bardi, Serie II. 83, [Galileo Galilei], Le Meccaniche del Galileo, mid-17th century copy. Carte Bardi, Serie II. 131, [D. Henrion], Trattati di geometria e fisica, 1623 Ceramelli Papiani 389: Tav. VIIIa [genealogical table of the Bardi family] Florence: Biblioteca Mediceo-Laurenziana Ashburnam 1217, Honoré Fabri, Synopsis recens Inventorum in Re Literaria et quibusdam aliis item comparationes literaria Auctore Honorato Fabri Societatis Jesu, c. 1669 Ashburnam 1312, [Trattati di Idraulica ecc.], c. 1699 Ashburnam 1450, [Libro di Rimedii e Segreti di Medicina], 17th century Ashburnam 1461, Lorenzo Incuria, Quaestiones Philosophicae in Libros Physicorum, 17th century Ashburnam 1811, [Lettere scritte a Vincenzo Viviani] Ashburnam 1818, [incl. letters to Lorenzo Magalotti] Redi 203, [Lettere scritte a Francesco Redi Aretino] Florence: Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale Manoscritti Galileiani 275 Manoscritti Galileiani 278 Manoscritti Galileiani 283 Manoscritti Galileiani 284 Florence: Biblioteca Riccardiana Riccardiani 2467 [incl. letters to Raffaello Magiotti] 352 Graz: Universitätsbibliothek Ms. 159 [letters to Paul Guldin] London: Archives of the Royal Society B I, no.99 Boyle Letters, VII, no. 56 D. 1, no. 18 EL. W3 no. 3 [copy in LBC 1 pp. 116-123] Malpighi Letters I, no. 8 MI, no.16 MM I, f.69 OB, no. 4 OB, no. 41 London: British Library Additional ms. 15,948 [incl. letters received by Samuel Hartlib] Additional ms. 22,804 [letters from Athanasius Kircher and Elio Loreti to Alessandro Segni, 1677/1678] Additional ms. -

And the Ends of Jesuit Science in Enlightenment Europe

Maximilian Hell (1720–92) and the Ends of Jesuit Science in Enlightenment Europe <UN> Jesuit Studies Modernity through the Prism of Jesuit History Editor Robert A. Maryks (Independent Scholar) Editorial Board James Bernauer, S.J. (Boston College) Louis Caruana, S.J. (Pontificia Università Gregoriana, Rome) Emanuele Colombo (DePaul University) Paul Grendler (University of Toronto, emeritus) Yasmin Haskell (University of Western Australia) Ronnie Po-chia Hsia (Pennsylvania State University) Thomas M. McCoog, S.J. (Loyola University Maryland) Mia Mochizuki (Independent Scholar) Sabina Pavone (Università degli Studi di Macerata) Moshe Sluhovsky (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem) Jeffrey Chipps Smith (The University of Texas at Austin) volume 27 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/js <UN> Maximilian Hell (1720–92) and the Ends of Jesuit Science in Enlightenment Europe By Per Pippin Aspaas László Kontler leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC-Nd 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The publication of this book in Open Access has been made possible with the support of the Central European University and the publication fund of UiT The Arctic University of Norway. Cover illustration: Silhouette of Maximilian Hell by unknown artist, probably dating from the early 1780s. (In a letter to Johann III Bernoulli in Berlin, dated Vienna March 25, 1780, Hell states that he is trying to have his silhouette made by “a person who is proficient in this.” The silhouette reproduced here is probably the outcome.) © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. -

From Influence to Inhabitation: the Transformation of Astrobiology in the Early Modern Period

1 From Influence to Inhabitation: The Transformation of Astrobiology in the Early Modern Period James Edward Christie Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. The Warburg Institute, School of Advanced Study University of London January 2018 2 I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: James Edward Christie 3 Abstract: This dissertation presents a conjoined and comparative history of astrology and the debate about the existence of extraterrestrial (ET) life in the early modern period. These two histories are usually kept separate, largely because the same period represents a certain terminus ad quem for the former and the terminus a quo for latter. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw the decline or marginalisation of astrology—the dismantling of the celestial causal chain of Aristotelian cosmology and the dismissal of any planetary or astral influence outside of light, heat and gravitation. They also saw the adoption, or re-adoption, of the cosmological view concerning the existence of a plurality of worlds in the universe (pluralism) and the possibility of ET life. Both these trends are considered as consequences of a Copernican cosmology and hallmarks of a modern worldview. The modern and in some sense artificial delineation between these two strands of historical enquiry (i.e. the history of astrology and the history of pluralism) may be detrimental, both to our understanding of celestial philosophy at any given time, as well as to our appreciation of cosmological change over longer periods. The most general and obvious similarity is that both these concepts meld astronomy and the life sciences. -

Michiel Florent Van Langren and Lunar Naming Peter Van Der Krogt, Ferjan Ormeling

ONOMÀSTICA BIBLIOTECA TÈCNICA DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA Michiel Florent van Langren and Lunar Naming Peter van der Krogt, Ferjan Ormeling DOI: 10.2436/15.8040.01.190 Abstract Michiel Florent van Langren produced a lunar map in 1645 in order to present a way to mariners to find their position at sea by observing which craters were either illuminated by solar rays or obscured during the waxing or waning of the moon. This required a detailed map of the moon and in order to be able to refer to lunar objects these had to be named. The lunar map he produced in 1645 bore over 300 names, following the system of subdividing lunar topography into land masses and seas (a distinction based on Plutarch), and craters or peaks. He is therefore the pioneer of both selenography and selenonymy. His nomenclature had no lasting impact, although some 50 names he introduced are still used for other craters. The same negative result was obtained by Johannes Hevelius who introduced in 1647 his own naming system based on geographical names. It was the nomenclature proposed by a third astronomer, Giovanni Riccioli, shown on his lunar map produced in 1651 that won the day. From the 244 names Riccioli proposed on his lunar map, 201 are still in use. Nevertheless, despite Van Langren’s lack of success, from a toponymical point of view his methodology is interesting as it provides insight into the contemporary world view of a seventeenth century scientist who was dependant on sponsors to allow him to carry out his work and transform his theories into practical instructions.