Michiel Florent Van Langren and Lunar Naming Peter Van Der Krogt, Ferjan Ormeling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy in Literature

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Press Libraries 1949 Philosophy in Literature Julian L. Ross Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/supress Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Ross, Julian L., "Philosophy in Literature" (1949). Syracuse University Press. 3. https://surface.syr.edu/supress/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Press by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OU_168123>3 ib VOOK t'l hvtent <J/ie tyovevnment //te ^United cf ai o an f.r^^fnto iii and yccdwl c/ tie llnited faaart/* *J/ie L/eofile of jf'ti OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY CallNo. 9ol//k?/^ Accession No. < Author ""jj^vv JLj. This book should be returned on or before the date last marked below. PHILOSOPHY IN LITERATURE PHILOSOPHY IN LITERATURE JULIAN L. ROSS Professor of English, Allegheny College SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY PRESS IN COOPERATION WITH ALLEGHENY COLLEGE Copyright, 1949 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY PRESS Only literature can describe experience, for the excellent reason that the terms of experience are moral and literary from the beginning. Mind is incorrigibly poetical: not be- cause it is not attentive to material facts and practical exigencies, but because, being intensely attentive to them, it turns them into pleasures and pains, and into many-colored ideas. GEORGE SANTAYANA TO CAROL MOODEY ROSS INTRODUCTION The most important questions of our time are philosoph- ical. All about us we see the clash of ideas and ideologies. Yet the formal study of philosophy has been losing rather than gaining ground. -

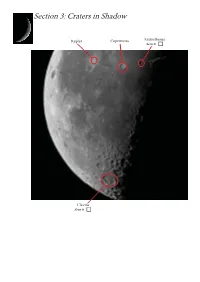

Craters in Shadow

Section 3: Craters in Shadow Kepler Copernicus Eratosthenes Seen it Clavius Seen it Section 3: Craters in Shadow Visibility: A pair of binoculars is the minimum requirement to see these features. When: Look for them when the terminator’s close by, typically a day before last quarter. Not all craters are best seen when the Sun is high in the lunar sky - in fact most aren’t! If craters aren’t par- ticularly bright or dark, they tend to disappear into the background when the Moon’s phase is close to full. These craters are best seen when the ‘terminator’ is nearby, or when the Sun is low in the lunar sky as seen from the crater. This causes oblique lighting to fall on the crater and create exaggerated shadows. Ultimately, this makes the crater look more dramatic and easier to see. We’ll use this effect for the next section on lunar mountains, but before we do, there are a couple of craters that we’d like to bring to your attention. Actually, the Moon is covered with a whole host of wonderful craters that look amazing when the lighting is oblique. During the summer and into the early autumn, it’s the later phases of the Moon are best positioned in the sky - the phases following full Moon. Unfortunately, this means viewing in the early hours but don’t worry as we’ve kept things simple. We just want to give you a taste of what a shadowed crater looks like for this marathon, so the going here is really pretty easy! First, locate the two craters Kepler and Copernicus which were marathon targets pointed out in Section 2. -

The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Author(S): Nicholas Overgaard Source: Prandium - the Journal of Historical Studies, Vol

Early Modern Catholic Defense of Copernicanism: The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Author(s): Nicholas Overgaard Source: Prandium - The Journal of Historical Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring, 2013), pp. 29-36 Published by: The Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto Mississauga Stable URL: http://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/prandium/article/view/19654 Prandium: The Journal of Historical Studies Vol. 2, No. 1, (2013) Early Modern Catholic Defense of Copernicanism: The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Nicholas Overgaard “Obedience should be blind and prompt,” Ignatius of Loyola reminded his Jesuit brothers a decade after their founding in 1540.1 By the turn of the seventeenth century, the incumbent Superior General Claudio Aquaviva had reiterated Loyola’s expectation of “blind obedience,” with specific regard to Jesuit support for the Catholic Church during the Galileo Affair.2 Interpreting the relationship between the Jesuits and Copernicans like Galileo Galilei through the frame of “blind obedience” reaffirms the conservative image of the Catholic Church – to which the Jesuits owed such obedience – as committed to its medieval traditions. In opposition to this perspective, I will argue that the Jesuits involved in the Galileo Affair3 represent the progressive ideas of the Church in the early seventeenth century. To prove this, I will argue that although the Jesuits rejected the epistemological claims of Copernicanism, they found it beneficial in its practical applications. The desire to solidify their status as the intellectual elites of the Church caused the Jesuits to reject Copernicanism in public. However, they promoted an intellectual environment in which Copernican studies – particularly those of Galileo – could develop with minimal opposition, theological or otherwise. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Sky and Telescope

SkyandTelescope.com The Lunar 100 By Charles A. Wood Just about every telescope user is familiar with French comet hunter Charles Messier's catalog of fuzzy objects. Messier's 18th-century listing of 109 galaxies, clusters, and nebulae contains some of the largest, brightest, and most visually interesting deep-sky treasures visible from the Northern Hemisphere. Little wonder that observing all the M objects is regarded as a virtual rite of passage for amateur astronomers. But the night sky offers an object that is larger, brighter, and more visually captivating than anything on Messier's list: the Moon. Yet many backyard astronomers never go beyond the astro-tourist stage to acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to really appreciate what they're looking at, and how magnificent and amazing it truly is. Perhaps this is because after they identify a few of the Moon's most conspicuous features, many amateurs don't know where Many Lunar 100 selections are plainly visible in this image of the full Moon, while others require to look next. a more detailed view, different illumination, or favorable libration. North is up. S&T: Gary The Lunar 100 list is an attempt to provide Moon lovers with Seronik something akin to what deep-sky observers enjoy with the Messier catalog: a selection of telescopic sights to ignite interest and enhance understanding. Presented here is a selection of the Moon's 100 most interesting regions, craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and domes. I challenge observers to find and observe them all and, more important, to consider what each feature tells us about lunar and Earth history. -

Pete Aldridge Well, Good Afternoon, Ladies and Gentlemen, and Welcome to the Fifth and Final Public Hearing of the President’S Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond

The President’s Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy PUBLIC HEARING Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY Monday, May 3, and Tuesday, May 4, 2004 Pete Aldridge Well, good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the fifth and final public hearing of the President’s Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond. I think I can speak for everyone here when I say that the time period since this Commission was appointed and asked to produce a report has elapsed at the speed of light. At least it seems that way. Since February, we’ve heard testimonies from a broad range of space experts, the Mars rovers have won an expanded audience of space enthusiasts, and a renewed interest in space science has surfaced, calling for a new generation of space educators. In less than a month, we will present our findings to the White House. The Commission is here to explore ways to achieve the President’s vision of going back to the Moon and on to Mars and beyond. We have listened and talked to experts at four previous hearings—in Washington, D.C.; Dayton, Ohio; Atlanta, Georgia; and San Francisco, California—and talked among ourselves and we realize that this vision produces a focus not just for NASA but a focus that can revitalize US space capability and have a significant impact on our nation’s industrial base, and academia, and the quality of life for all Americans. As you can see from our agenda, we’re talking with those experts from many, many disciplines, including those outside the traditional aerospace arena. -

Revised Final MASTERS THESIS

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Carlo Fontana and the Origins of the Architectural Monograph A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Juliann Rose Walker June 2016 Thesis Committee: Dr. Kristoffer Neville, Chairperson Dr. Jeanette Kohl Dr. Conrad Rudolph Copyright by Juliann Walker 2016 The Thesis of Juliann Rose Walker is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would first like to start by thanking my committee members. Thank you to my advisor, Kristoffer Neville, who has worked with me for almost four years now as both an undergrad and graduate student; this project was possible because of you. To Jeanette Kohl, who was integral in helping me to outline and finish my first chapter, which made the rest of my thesis writing much easier in comparison. Your constructive comments were instrumental to the clarity and depth of my research, so thank you. And thank you to Conrad Rudolph, for your stern, yet fair, critiques of my writing, which were an invaluable reminder that you can never proofread enough. A special thank you to Malcolm Baker, who offered so much of his time and energy to me in my undergraduate career, and for being a valuable and vast resource of knowledge on early modern European artwork as I researched possible thesis topics. And the warmest of thanks to Alesha Jeanette, who has always left her door open for me to come and talk about anything that was on my mind. I would also like to thank Leigh Gleason at the California Museum of Photography, for giving me the opportunity to intern in collections. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

10Great Features for Moon Watchers

Sinus Aestuum is a lava pond hemming the Imbrium debris. Mare Orientale is another of the Moon’s large impact basins, Beginning observing On its eastern edge, dark volcanic material erupted explosively and possibly the youngest. Lunar scientists think it formed 170 along a rille. Although this region at first appears featureless, million years after Mare Imbrium. And although “Mare Orien- observe it at several different lunar phases and you’ll see the tale” translates to “Eastern Sea,” in 1961, the International dark area grow more apparent as the Sun climbs higher. Astronomical Union changed the way astronomers denote great features for Occupying a region below and a bit left of the Moon’s dead lunar directions. The result is that Mare Orientale now sits on center, Mare Nubium lies far from many lunar showpiece sites. the Moon’s western limb. From Earth we never see most of it. Look for it as the dark region above magnificent Tycho Crater. When you observe the Cauchy Domes, you’ll be looking at Yet this small region, where lava plains meet highlands, con- shield volcanoes that erupted from lunar vents. The lava cooled Moon watchers tains a variety of interesting geologic features — impact craters, slowly, so it had a chance to spread and form gentle slopes. 10Our natural satellite offers plenty of targets you can spot through any size telescope. lava-flooded plains, tectonic faulting, and debris from distant In a geologic sense, our Moon is now quiet. The only events by Michael E. Bakich impacts — that are great for telescopic exploring. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

October 2006

OCTOBER 2 0 0 6 �������������� http://www.universetoday.com �������������� TAMMY PLOTNER WITH JEFF BARBOUR 283 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 1 In 1897, the world’s largest refractor (40”) debuted at the University of Chica- go’s Yerkes Observatory. Also today in 1958, NASA was established by an act of Congress. More? In 1962, the 300-foot radio telescope of the National Ra- dio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) went live at Green Bank, West Virginia. It held place as the world’s second largest radio scope until it collapsed in 1988. Tonight let’s visit with an old lunar favorite. Easily seen in binoculars, the hexagonal walled plain of Albategnius ap- pears near the terminator about one-third the way north of the south limb. Look north of Albategnius for even larger and more ancient Hipparchus giving an almost “figure 8” view in binoculars. Between Hipparchus and Albategnius to the east are mid-sized craters Halley and Hind. Note the curious ALBATEGNIUS AND HIPPARCHUS ON THE relationship between impact crater Klein on Albategnius’ southwestern wall and TERMINATOR CREDIT: ROGER WARNER that of crater Horrocks on the northeastern wall of Hipparchus. Now let’s power up and “crater hop”... Just northwest of Hipparchus’ wall are the beginnings of the Sinus Medii area. Look for the deep imprint of Seeliger - named for a Dutch astronomer. Due north of Hipparchus is Rhaeticus, and here’s where things really get interesting. If the terminator has progressed far enough, you might spot tiny Blagg and Bruce to its west, the rough location of the Surveyor 4 and Surveyor 6 landing area. -

August 2017 Posidonius P & Luther

A PUBLICATION OF THE LUNAR SECTION OF THE A.L.P.O. EDITED BY: Wayne Bailey [email protected] 17 Autumn Lane, Sewell, NJ 08080 RECENT BACK ISSUES: http://moon.scopesandscapes.com/tlo_back.html FEATURE OF THE MONTH – AUGUST 2017 POSIDONIUS P & LUTHER Sketch and text by Robert H. Hays, Jr. - Worth, Illinois, USA March 5, 2017 01:28-01:48; UT, 15 cm refl, 170x, seeing 7-8/10. I drew these craters on the evening of March 4/5, 2017 while the moon was hiding some Hyades stars. This area is in northeast Mare Serenitatis west of Posidonius itself. Posidonius P is the largest crater on this sketch. The smaller crater south of P is Posidonius F and Posidonius G is the tiny pit to the north. There is a halo around Posidonius G, but this crater is noticeably north of the halo's center. A very low round swelling is northeast of Posidonius G. Luther is the crater well to the west of Posidonius P. All four of these craters are crisp, symmetric features, differing only in size. There are an assortment of elevations near Luther. The peak Luther alpha is well to the west of Luther, and showed dark shadowing at this time. All of the other features near Luther are more subtle than Luther alpha. One mound is between Luther and Luther alpha. Two more mounds are north of Luther, and a low ridge is just east of this crater. A pair of very low mounds are south of Luther. These are the vaguest features depicted here, and may be too conspicuous on the sketch.