The Watershed: a Biography of Johannes Kepler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music in Time

MUSIC MUSIC IN TIME John Kennedy, Director and Host PROGRAM I: LISTENING TO FRAGRANCES OF THE DUSK Simons Center Recital Hall at College of Charleston May 27 at 5:00pm Meditation (2012) Toshio Hosokawa (b. 1955) AMERICAN PREMIERE Symphony No. 8 – Revelation 2011 (2011) Toshi Ichiyanagi (b. 1933) AMERICAN PREMIERE Listening to Fragrances of the Dusk (1997) Somei Satoh (b. 1947) AMERICAN PREMIERE John Kennedy, conductor Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra PROGRAM II: THE BOWED PIANO ENSEMBLE Memminger Auditorium May 29 at 8:00pm Rainbows, Parts One and Two (1981) Stephen Scott (b. 1944) Aurora Ficta (2008) Excerpts from Paisajes Audibles/Audible Landscapes (2002) Azul En su Isla Victoria Hansen, soprano 1977: Music of Three Worlds (2012) WORLD PREMIERE I. Genesis: Charleston, Colorado Springs, Kealaikahiki, Spring 1977 II. Saba Saba Saba Saba (7/7/77): Dar es Salaam III. Late Summer Waltz/Last Waltz in Memphis The Bowed Piano Ensemble Founder, Director and Composer Stephen Scott Soprano Victoria Hansen The Ensemble Trisha Andrews Zachary Bellows Meghann Maurer Kate Merges Brendan O’Donoghue Julia Pleasants Andrew Pope A.J. Salimbeni Nicole Santilli Stephen Scott 84 MUSIC MUSIC IN TIME PROGRAM III: CONVERSATION WITH PHILIP GLASS Dock Street Theatre June 2 at 5:00pm Works to be announced from the stage. Members of the Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra PROGRAM IV: DRAMAS Simons Center Recital Hall at College of Charleston June 7 at 5:00pm Grind Show (unplugged) (2008) Tansy Davies (b. 1973) AMERICAN PREMIERE Island in Time (2012) John Kennedy (b. 1959) Drama, Op. 23 (1996) Guo Wenjing (b. 1956) I – II – III – IV – V – VI Members of the Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra JOHN KENNEDY (conductor, director PHILIP GLASS (composer, Program III), and host), Spoleto Festival USA Resident born in Baltimore, Maryland, is a graduate Conductor, has led acclaimed performances of the University of Chicago and The and premieres worldwide of opera, ballet, Juilliard School. -

2-Minute Stories Galileo's World

OU Libraries National Weather Center Tower of Pisa light sculpture (Engineering) Galileo and Experiment 2-minute stories • Bringing worlds together: How does the story of • How did new instruments extend sensory from Galileo exhibit the story of OU? perception, facilitate new experiments, and Galileo and Universities (Great Reading Room) promote quantitative methods? • How do universities foster communities of Galileo and Kepler Galileo’s World: learning, preserve knowledge, and fuel • Who was Kepler, and why was a telescope Bringing Worlds Together innovation? named after him? Galileo in Popular Culture (Main floor) Copernicus and Meteorology Galileo’s World, an “Exhibition without Walls” at • What does Galileo mean today? • How has meteorology facilitated discovery in the University of Oklahoma in 2015-2017, will History of Science Collections other disciplines? bring worlds together. Galileo’s World will launch Music of the Spheres Galileo and Space Science in 21 galleries at 7 locations across OU’s three • What was it like to be a mathematician in an era • What was it like, following Kepler and Galileo, to campuses. The 2-minute stories contained in this when music and astronomy were sister explore the heavens? brochure are among the hundreds that will be sciences? Oklahomans and Aerospace explored in Galileo’s World, disclosing Galileo’s Compass • How has the science of Galileo shaped the story connections between Galileo’s world and the • What was it like to be an engineer in an era of of Oklahoma? world of OU during OU’s 125th anniversary. -

July 2020- Harmony

Touchstones a monthly journal of Unitarian Universalism July 2020 Harmony Wisdom Story “Islam is ...a practice, a way of life, a Making Beautiful Justice pattern for establishing harmony with Rev. Kirk Loadman-Copeland God and his creation.” Harmony with His father was a Harvard-trained pro- the divine is also a foundation of mysti- fessor of musicology and his mother, cism. who trained at the Paris Conservatory of Within our own tradition, our com- Music, was a classical violinist. But he mitment to social harmony is affirmed never cared for classical music, which in a number of our principles, including may explain why he began to play the “justice, equity, and compassion in hu- ukulele at the age of 13. He also learned Introduction to the Theme man relations” and “the goal of world to play the guitar. In 1936, when he was While there are efforts at harmony community with peace, liberty, and jus- seventeen, he fell in love with a five- among world religions, the emphasis on tice for all.” string banjo. He heard it at the Mountain harmony varies within the different Harmony with nature figured promi- Dance and Folk Festival in western North world religions. Social harmony figures nently among the Transcendentalists, Carolina near Asheville. Perhaps the prominently in Asian Religions like Tao- especially Thoreau. This emphasis on banjo chose him, since a person once said ism, Confucianism, Buddhism, Hindu- harmony is expressed in both our sev- that he actually looked like a banjo. He ism, and Sikhism, while harmony with enth principle, “respect for the interde- would later say, “I lost my heart to the nature is emphasized in Taoism, Neo- pendent web of all existence of which old-fashioned five-string banjo played pagan, and Native American traditions. -

Kepler's Cosmological Synthesis

Kepler’s Cosmological Synthesis History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 39 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J. M. M. H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C. H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 20 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Kepler’s Cosmological Synthesis Astrology, Mechanism and the Soul By Patrick J. Boner LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Kepler’s Supernova, SN 1604, appears as a new star in the foot of Ophiuchus near the letter N. In: Johannes Kepler, De stella nova in pede Serpentarii, Prague: Paul Sessius, 1606, pp. 76–77. Courtesy of the Department of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Milton S. Eisenhower Library, Johns Hopkins University. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Boner, Patrick, author. Kepler’s cosmological synthesis: astrology, mechanism and the soul / by Patrick J. Boner. pages cm. — (History of science and medicine library, ISSN 1872-0684; volume 39; Medieval and early modern science; volume 20) Based on the author’s doctoral dissertation, University of Cambridge, 2007. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-24608-9 (hardback: alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-24609-6 (e-book) 1. Kepler, Johannes, 1571–1630—Philosophy. 2. Cosmology—History. 3. Astronomy—History. I. Title. II. Series: History of science and medicine library; v. 39. III. Series: History of science and medicine library. Medieval and early modern science; v. 20. QB36.K4.B638 2013 523.1092—dc23 2013013707 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. -

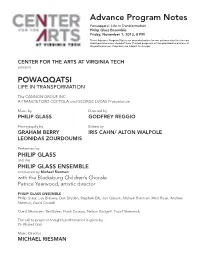

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

Spring 2010 Number 4 Spring Meeting at Kent State University April 16-17, 2010

hio Focus The MAA Ohio Section Newsletter Volume 9 Spring 2010 Number 4 Spring Meeting at Kent State University April 16-17, 2010 The Spring Meeting of the Ohio Section MAA will be held at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, on April 16-17, 2010. The meeting will start at noon on Friday, with the first invited lecture starting at 1:45 pm in Henderson Hall, and will conclude on Saturday at 1:00 pm. Major addresses will be given by Karen Parshall of The University of Virgina, John Oprea of Cleveland State University, Ivars Peterson, the Director of Publications and Communications for the MAA, and Mark Miller of Marietta College. Other meeting participants are encouraged to submit talks for the contributed paper sessions on Friday afternoon and Saturday morning. Graduate and undergraduate students in Mathematics and Computer Science Building: Meeting Registration Location mathematics or mathematics education are encouraged to attend. It All Started in Ohio Meeting Registration Centennial Note #1 Inside Online registration is preferred. It is a well-known fact that the Visit the Section web site at Spring Meeting Details Mathematical Association of www.maa.org/Ohio on or after America was organized in Page Tuesday, March 2, for one-stop Hall, on the Ohio State University registration, banquet reservation, Governor’s Report campus, December 30-31, 1915. and abstract submission. The But before MAA there was AMM – deadline for meeting pre- President’s Message the American Mathematical registration and banquet reser- Monthly. This journal began as a vations is April 9. Abstracts for Nominations for Section private enterprise, published at contributed papers must be Officers Kidder, Missouri, starting in January submitted by April 2. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 Si Tantus Amor Belli Tibi, Roma, Nefandi. Love and Strife in Lucan's Bellum Civile Giulio Celotto Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES SI TANTUS AMOR BELLI TIBI, ROMA, NEFANDI. LOVE AND STRIFE IN LUCAN’S BELLUM CIVILE By GIULIO CELOTTO A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Giulio Celotto defended this dissertation on February 28, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Tim Stover Professor Directing Dissertation David Levenson University Representative Laurel Fulkerson Committee Member Francis Cairns Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above5na ed co ittee e bers, and certifies that the dissertation has been appro0ed in accordance 1ith uni0ersity require ents. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The co pletion of this dissertation could not ha0e been possible 1ithout the help and the participation of a nu ber of people. It is a great pleasure to be able to ac3no1ledge the here. I a ost grateful to y super0isor, Professor Ti Sto0er, for his guidance and dedication throughout the entire ti e of y research. I 1ish to e6tend y than3s to the other Co ittee e bers, Professors Laurel Ful3erson, Francis Cairns, and Da0id Le0enson, for their ad0ice at e0ery stage of y research. I 1ould li3e to e6press y deepest gratitude to Professor Andre1 7issos, 1ho read the entire anuscript at a later stage, and offered any helpful suggestions and criticis s. -

The Dr. Jeckyl and Mr. Hyde of 20Th Century Intellectual History

The Dr. Jeckyl and Mr. Hyde of 20th Century Intellectual History ANYONE INTERESTED in intellectual history from the great depression of the thirties to the post war 1980s will be familiar with the impact of Arthur Koestler, whose famous assault on Stalinism and the Soviet Union in his novel Darkness at Noon was a widely praised international bestseller. There was a vehemently critical biography written by David Cesurani, Arthur Koestler—The Homeless Mind published in London in 1998. It was an opinionated attack on Koestler’s personality and moral stature. It also portrayed him as a brutal womanizer and a self-loathing Jew. A more scholarly biography has now appeared written by Michael Scammell, the well-known biographer of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Scammell’s work does not have the polemical, hyperbolic prose of Cesurani but it too is a strongly opinionated defense of Koestler, seeing him as one of the greatest intellectual journalists and writers of the 20th century. Scammell describes Koestler as a Dr. Jeckyl and Mr. Hyde, both intellectually brilliant and often mean-spirited, a bourgeois in domestic habits, bohemian in public, both idealistic and cynical, generous and kind on the one hand and brutal and even violent on the other. Books about Koestler are not likely to be written with a detached scholarly disinterest. Scammell’s biography is nearly 700 pages long. It has been acclaimed as a masterpiece of intellectual history. Koestler had an extraordinarily full life participating in nearly every intellectual, cultural, and scholarly debate and controversy of his time as well as being an actual participant in many major events including the Spanish Civil War, World War II and as a dissident voice throughout the post war years. -

By Christopher Reed

Gingerich.final 10/6/03 7:07 PM Page 44 The Copernicus Quest How an astrophysicist with a “collecting gene” became the world’s authority on a revolutionary, allegedly unread book by Christopher Reed wen gingerich, ph.d. ’62, takes a seat revoluty-own-ibus” is a good approximation of its proper pro- on his “rocket cart”—a dolly with a steer- nunciation, says Gingerich. Its title page reminds him of an op- ing stick in front, a straight-backed chair tometrist’s chart: amidship, and a big fire-extinguisher NICOLAUS CO mounted at back. Donning a crash helmet PERNICUS OF TORUN and an aviator’s scarf for the trip, he reaches about the revolutions of behind him and turns on the extinguisher, the Heavenly Spheres in Six Books. which releases a propulsive jet of carbon dioxide. The cart begins to move across the floor of the Science Copernicus argued against the conventional wisdom, promul- Center lecture hall. Gingerich picks up speed until he is accelerat- gated by Claudius Ptolemy in Alexandria around a.d. 150, that ing furiously with a look of terror on his face toward a side door, the earth was fixed at the middle of the universe. He proposed which flies open just in time and out he goes. Assistants in the instead that what could be observed of planetary motion could wings drop “a big sack full of pipes,” he explains, which make a be explained if the sun was immovable in the middle, with the huge clatter o≠ stage. Gingerich is demonstrating Newton’s third earth and other planets going around it, the modern understand- Olaw, that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. -

Maslach, Doris.Book

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California UNIVERSITY HISTORY Doris Maslach A LIFE HISTORY WITH DORIS MASLACH An interview conducted by Nadine Wilmot in 2004 Copyright © 2007 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Doris Maslach, dated February 3, 2006. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Arthur Koestler's Hope in the Unseen: Twentieth-Century Efforts to Retrieve the Spirit of Liberalism" (2005)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Arthur Koestler's hope in the unseen: twentieth- century efforts to retrieve the spirit of liberalism Kirk Michael Steen Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Steen, Kirk Michael, "Arthur Koestler's hope in the unseen: twentieth-century efforts to retrieve the spirit of liberalism" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1669. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ARTHUR KOESTLER’S HOPE IN THE UNSEEN: TWENTIETH-CENTURY EFFORTS TO RETRIEVE THE SPIRIT OF LIBERALISM A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Kirk Steen B. A., University of New Orleans, 1974 M. A., University of New Orleans, 1986 August 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Kirk Michael Steen All rights reserved ii Arthur Koestler at his desk during the 1930s iii Dedication The efforts that produced this investigation of Arthur Koestler I offer to my wife, Christel Katherine Roesch, for her patient support and for the value and respect she holds for liberal education. The two of us share one fundamental belief that justifies the changes in our lifestyle necessitated by my earning a terminal degree and completing the narrative that follows. -

Europack 2004

www.eurovision-spain.com XLIX Festival de eurovisión Estambul – Turquía – 12 y 15 de mayo de 2003 Europack 2004 SEMIFINAL visítanos en www.eurovision-spain.com europack 2003 | pág 1 www.eurovision-spain.com XLIX Festival de eurovisión Estambul – Turquía – 12 y 15 de mayo de 2003 Estimados visitantes y amigos de www.eurovision-spain.com ya tenemos aquí un nuevo festival de eurovisión, en esta ocasión con dos galas, la final y la semifinal , hemos llegado al fin del camino que comenzamos hace casi un año siguiendo todo el proceso de organización del festival, casi 365 intentando ofreceros la mejor información y servicios, porque eurovisión se vive más que un día al año. Como hicimos el año pasado aquí teneis nuestro europack, pero en esta ocasión dividido en dos partes para sigáis el festival con toda la información que necesitéis en cada momento, lista de países, canciones, letras en versión original y traducción al castellano y tablero de puntuaciones total, todo ello para que tan sólo tengas que imprimirlo y empezar a vivir el festival desde ahora. El Europack de la final será publicado una vez se conozcan los finalistas Gracias a todos por vuestro apoyo durante esta temporada eurovisiva y esperamos contar con todos en la nueva que hoy comienza para el festival de la canción de eurovisión. Saludos a todos y gracias en nombre de todos los que hacemos www.eurovisión-spain.com europack 2003 | pág 2 www.eurovision-spain.com XLIX Festival de eurovisión Estambul – Turquía – 12 y 15 de mayo de 2003 Lista de participantes: XLIX Festival de Eurovisión final: 15/05/04 | semifinal: 12/05/04 Sede: Estambul, Turquía - Abdi Ipekci Votación: de 1 a 8, 10 y 12 - (votos alfabéticamente 36-final y 33-semi) Participantes: 14 finalistas + 10 semifinalistas Semifinal nº País Intérprete - canción pts.