Unit 21 Agric'ultural Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Banaras: a City of Cultural and Economic Dynamics and Response

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT. – DEC. 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Medieval Banaras: A City of Cultural and Economic Dynamics and Response Pritam Kumar Gupta Research Scholar, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Received: November 12, 2018 Accepted: December 17, 2018 ABSTRACT This paper attempts to understand the cultural and economic importance of the city of Banarasto various medieval political powers.As there are many examples on the basis of which it can be said that the nature, dynamics, and popularity of a city have changed at different times according to the demands and needs of the time. Banaras is one of those ancient cities which has been associated with various religious beliefs and cultures since ancient times but the city, while retaining its old features, established itself as a developed trade city by accepting new economic challenges, how the Banaras provided a suitable environment to the changing cultural and economic challenges, whereas it went through the pressure of different political powers from time to time and made them realize its importance. This paper attempts to understand those suitable environmentson how the landscape of Banaras and its dynamics in the medieval period transformed this city into a developed economic-cultural city. Keywords: Banaras, Religious, Economic, Urbanization, Mughal, Market, Landscape. Wide-ranging literary works have been written on Banaras by scholars of various subject backgrounds, in which they highlight the socio-economic life of different religious and cultural ideals of the inhabitants of Banaras. It is very important for scholars studying regional history to understand what challenges a city has to face in different historical periods to maintain its identity.The name Banaras is found as the present name Varanasi in the Buddhist Jataka and Hindu epic Mahabharata. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

The Core and the Periphery: a Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century Author(S): Z

Social Scientist The Core and the Periphery: A Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century Author(s): Z. U. Malik Source: Social Scientist, Vol. 18, No. 11/12 (Nov. - Dec., 1990), pp. 3-35 Published by: Social Scientist Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3517149 Accessed: 03-04-2020 15:29 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Social Scientist is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Scientist This content downloaded from 117.240.50.232 on Fri, 03 Apr 2020 15:29:21 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Z.U. MALIK* The Core and the Periphery: A Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century** There is a general unanimity among modern historians on seeing the dissolution of Mughal empire as a notable phenomenon cf the eighteenth century. The discord of views relates to the classification and explanation of historical processes behind it, and also to the interpretation and articulation of its impact on political and socio- economic conditions of the country. Most historians sought to explain the imperial crisis from the angle of medieval society in general, relating it to the character and quality of people, and the roles of the diverse classes. -

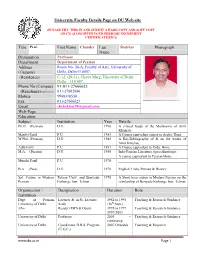

Title Prof. First Name Chander Last Name Photograph Designation

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND SUBMIT A HARD COPY AND SOFT COPY ON CD ALONGWITH YOUR PERIODIC INCREMENT CERTIFICATE(PIC)) Title Prof. First Name Chander Last Shekhar Photograph Name Designation Professor Department Department of Persian Address Room No- 58-A, Faculty of Arts, University of (Campus) Delhi, Delhi-110007. (Residence) C-12, (29-31), Chatra Marg, University of Delhi Delhi – 110 007. Phone No (Campus) 91-011-27666623 (Residence)optional 011-27662086 Mobile 9968318530 Fax 011-27666623 Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. (Persian) D.U. 1990 A critical Study of the Mathnawis of Amir Khusrau. Maulvi Fazil P.U. 1983 A Course equivalent course to Arabic Hons. M.Phil. (Persian) D.U. 1982 A Bio-Bibliography of & on the works of Amir Khusrau Adib Fazil P.U 1981 A Course equivalent to Urdu. Hons. M.A. (Persian) D.U. 1980 Indo-Persian Literature.(specialization)s A course equivalent to Persian Hons. Munshi Fazil P.U 1978 B.A. (Pass) D.U.. 1978 English. Urdu, Persian & History Spl. Course in Modern Tehran Univ. and Bonyade- 1978 A Short term course in Modern Persian on the Persian Farhange Iran, Tehran scholarship of Bonyade Farhange Iran, Tehran Organisation / Designation Duration Role Institution Dept. of Persian, Lecturer & in Sr. Lecturer 1982 to 1995 Teaching & Research Guidance University of Delhi Scale (16th Sept.) -Do- Reader (MPS & Open) 1995 to 1997 Teaching & Research Guidance 1997-2003 University of Delhi Professor 2003 – Teaching & Research Guidance continuing University of Delhi Coordinator D.R.S. -

Economy of Transport in Mughal India

ECONOMY OF TRANSPORT IN MUGHAL INDIA ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Bottor of ^t)tla£foplip ><HISTORY S^r-A^. fi NAZER AZIZ ANJUM % 'i A ^'^ -'mtm''- kWgj i. '* y '' «* Under the Supervision of PROFESSOR SHIREEN MOOSVI CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 4LIGARH (INDIA) 2010 ABSTRACT ]n Mughal India land revenue (which was about 50% of total produce) was mainly realised in cash and this resulted in giving rise to induced trade in agricultural produce. The urban population of Mughal India was over 15% of the total population - much higher than the urban population in 1881(i.e.9.3%). The Mughal ruling class were largely town-based. At the same time foreign trade was on its rise. Certain towns were emerging as a centre of specialised manufactures. These centres needed raw materials from far and near places. For example, Ahmadabad in Gujarat a well known centre for manufacturing brocade, received silk Irom Bengal. Saltpeter was brought from Patna and indigo from Biana and adjoining regions and textiles from Agra, Lucknow, Banaras, Gazipur to the Gujarat ports for export. This meant development of long distance trade as well. The brisk trade depended on the conditions and techniques of transport. A study of the economy of transport in Mughal India is therefore an important aspect of Mughal economy. Some work in the field has already been done on different aspects of system of transport in Mughal India. This thesis attempts a single study bringing all the various aspects of economy of transport together. -

Unit 21 Agric'ultural Production

.UNIT 21 AGRIC'ULTURAL PRODUCTION. structure 21.0 Objectives 21.1 Introduction 21.2 Extent of Cultivation 21.3 Means of Cultivation and Imgation 21.3.1 Means and Methods of Cultivation 21.3.2 Means of Imgation 21.4 Agricultural Produce 21.4.1 Food Crops 21.4.2 Cash Crops 21.4.3 Fruits, Vegetables and Spices 21.4.4 Productivity and Yields 21.5 Cattle and Livestock 21.6 Let Us Sum Up 21.7 Key Words 21.8 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises This Unit deals with agricultural production in India during the period of this study. After going through this Unit you would have an idea about the extent of cultivation during the period under study; know about the means and methods of cultivation and irrigation; be able.to list the main crops grown; and have some idea about the status of livestock and cattle breeding. 21.1 INTRODUCTION India has a very large land area with diverse climatic zones. Throughout its history, agriculture has been its predominant productive activity. During the Mughal period, large tracts of land were under the plough. Contemporary Indian and foreign writers praise the fertility of Indian soil. In this Unit, we will discuss many aspects including the extent of cultivation, that is the land under plough. A wide rangdof food crops, fruits, vegetables and crop were grown in India. However, we would take a stock only of the main crop grown during this period. We will also discuss the methods of cultivation as also the implements used for cultivation and irrigation technology. -

In Size but Invariably in a Position Proving Them to Be Retreating Baffled and Beaten, Were Intended to Represent the Asuras, Po

1110 NOTICES OF BOORS in size but invariably in a position proving them to be retreating baffled and beaten, were intended to represent the Asuras, powers of darkness and evil, humbled by and retiring before the presence of the life-giving deity. From my own point of view the most serious mistake in the book is to be found in the note to vol. i, p. 126, where the author, of course by pure accident, does me the entirely undeserved honour of attributing to me the authorship of Mr. Vincent Smith's Fine Art in India. The error is much to be regretted. R. SEWELL. CATALOGUE OF COINS IN THE PANJAB MUSEUM, LAHORE. By R. B. WHITEHEAD. Oxford, 1914. (Continued from the July Part, p. 795.) The second volume of this Catalogue deals with the coins of the Mughal Emperors of India, an important series which until recent times has not received adequate attention from numismatists. The revival of interest in the subject may be said to date from the publication of the British Museum Catalogue in 1892 and from the researches of Mr. C. J. Rodgers in the Panjab. The British Museum cabinet then contained about 1,250 coins, a number now greatly increased. The recent activity in this branch of numismatics may be measured by the fact that the Indian Museum at Calcutta, which contained 863 Mughal coins in 1894, contained 2,560 when Mr. Nelson Wright's Catalogue was issued in 1908, and the Lahore cabinet catalogued by Mr. C. J. Rodgers in 1892, and consisting mainly of his own collection, contained 1,559 Mughal coins, whereas the present Catalogue shows 3,283, the greatest number published as yet in any catalogue. -

India from 16Th Century to Mid-18Th Century

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology India from 16th Century to Mid 18th Century Subject: INDIA FROM 16TH CENTURY TO MID 18TH CENTURY Credits: 4 SYLLABUS India in the 16th Century The Trading World of Asia and the Coming of the Portuguese, Polity and Economy in Deccan and South India, Polity and Economy in North India, Political Formations in Central and West Asia Mughal Empire: Polity and Regional Powers Relations with Central Asia and Persia, Expansion and Consolidation: 1556-1707, Growth of Mughal Empire: 1526-1556, The Deccan States and the Mughals, Rise of the Marathas in the 17th Century, Rajput States, Ahmednagar, Bijapur and Golkonda Political Ideas and Institutions Mughal Administration: Mansab and Jagir, Mughal Administration: Central, Provincial and Local, Mughal Ruling Class, Mughal Theory of Sovereignty State and Economy Mughal Land Revenue System, Agrarian Relations: Mughal India, Land Revenue System: Maratha, Deccan and South India, Agrarian Relations: Deccan and South India, Fiscal and Monetary System, Prices Production and Trade The European Trading Companies, Personnel of Trade and Commercial Practices, Inland and Foreign Trade Non-Agricultural Production, Agricultural Production Society and Culture Population in Mughal India, Rural Classes and Life-style, Urbanization, Urban Classes and Life-style Religious Ideas and Movements, State and Religion, Painting and Fine Arts, Architecture, Science and Technology, Indian Languages and Literature India at the Mid 18th Century Potentialities of Economic Growth: An Overview, Rise of Regional Powers, Decline of the Mughal Empire Suggested Readings 1. -

Suba of Delhi Under the Mughals 1580-1719

SUBA OF DELHI UNDER THE MUGHALS 1580-1719 ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE Ph. D. DEGREE By ABHA SINGH SUPERVISOR : PROFESSOR IRFAN HABIB CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY IN HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 1988 ., ^N^ A2AD _ ABSTRACT ,^^r ^^^ ^^ ^ • % The thesis alms at studying varfoui?^ €!^9nondc; jiolitical and administrative aspects of the Mughal province of Delhi from 1580 to I7l9. Introduction gives the sources on which the thesis is based. All kinds of material, notably Persian historical works and records of ell kinds; Raj asthan! documents and accounts of European travellers have been used. The stud/ begins by establishing the limits of the euba, as well as of its divisions/ and the changes made in them from time to time, ^he physical geography of the area is then studied, with special reference to rainfall lines Cisohyets). An element of human geography alters by correlat ing Mughal administrative boundaries with the linguistic boundaries (after Griereon). An actual correspondence between administrative and linguistic boundaries has not however been established. (Chapter I). Chapter II deals with the pattern of Agricultural production in the suba. It has been found that the extent of cultivation increased greatly between the reigns of Akbar and Aurangzeb. Price variations are also been discussed. The price-data suggests that there wasaxise in the value of wheat between 1595 and 1715. - 2 - Data on mineral productions and manufactures (&3De brought together in Chapter III. This is followed by an analysis of the Land-revenue system in the guba. A comparison of dastur-rates, with Sher shah's rai* and modern yields has been attempted. -

Composition and Role of the Nobility (1739-1761)

COMPOSITION AND ROLE OF THE NOBILITY (1739-1761) ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of ^l)iIo^op}|p IN HISTORY BY MD. SHAKIL AKHTAR Under the Supervision of DR. S. LIYAQAT H. MOINI (Reader) CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2008 ABSTRACT Foregoing study ' composition and role of the Nobility (1739- 1761)', explore the importance of Nobility in Political, administrative, Sicio-cultural and economic spheres. Nobility , 'Arkan-i-Daullat' (Pillars of Empire) generally indicates'the'class of people, who were holding hi^h position and were the officers of the king as well as of the state. This ruling elite constituting of various ethnic group based on class, political sphere. In Indian sub-continent they served the empire/state most loyally and obediently specially under the Great Mughals. They not only helped in the expansion of the Empire by leading campaign and crushing revolt for the consolidation of the empire, but also made remarkable and laudable contribution in the smooth running of the state machinery and played key role in the development of social life and composite culture. Mughal Emperor Akbar had organized the nobility based on mgnsabdari system and kept a watchful eye over the various groups, by introducing local forces. He had tried to keep a check and balance over the activities, which was carried by his able successors till the death of Aurangzeb. During the period of Later Mughals over ambitious, self centered and greedy nobles, kept their interest above state and the king and had started to monopolies power and privileges under their own authority either at the court or in the far off provinces. -

MUGHAL SUBA Or" the DJSCCAN (1636-56) Ahmadnagar Kingdom Was Annexed to Sthe Mughal L^Pire During the Reign of Shah Jahan

MUGHAL SUBA Or" THE DJSCCAN (1636-56) Ahmadnagar kingdom was annexed to sthe Mughal l^pire during the reign of Shah Jahan, After its annexation the Mughal aathority In the south had entered a new phase of its development. Resistance in Berar had come to an end and inten sive exploitation of the Deccan had started. Major revenue refoims were introduced during this period and significant changes were introduced In other spheres of administratia>n. This thesis is a humble attempt to investigate the impact of Mughal rule on the political and socio-economic trends in the Deccan during this period in the light of documents available in the State Archives at Hyderabad, Most of the archival material on which this thesis is based had not been utilised so far. The study does not deal with the entire Deccan, but only with that part of the Deccan which formed a part of the Mughal Empire till 1656, The first Chapter deals with the political, physical and ethnic geography of the area. In this chapter, Mughal pene tration right from the time of Akbar till 1636, has been traced. With the appointment of Prince Aurangzeb, as the Viceroy of the Deccan in 1636, the area started to feel the impact of Mughal adminis tration. * li - It has been shown that there was no major change in the boundaries of the jg^rKftTS or PMMmM* "J^ii® p^yg^ag assigned to a sarkar were rarely transferred from one to another. The number of pareanas attached to a sarkar was also left almost untouched. -

Unit 23 Urban Patterns in Medieval Deccan*

UNIT 23 URBAN PATTERNS IN MEDIEVAL DECCAN* Structure 23.1 Introduction 23.2 Golconda 23.3 Bijapur 23.4 Industrial Cities of the Deccan 23.4.1 Textile Centres 23.4.2 Saltpetre and Gunpowder Production Centres 23.4.3 Diamond Industries and the Urban Growth 23.5 Manufacturing Town: Bidar 23.6 Summary 23.7 Exercises 23.8 References 23.1 INTRODUCTION Studies on urbanisation of the Deccan have, on the whole, been rather limited, leading often to the impression that there was very little urbanisation in the region. This is far from being the case, for there were, historically, a large number of urban settlements visible here from fairly early time. Ranabir Chakravarti has, for instance, pointed to the presence of inscriptions to the existence of terms such as mandapikā, petha or penthā, nagaram, and śulkasthāna, all of which refer to market centres. We can therefore talk of the existence of a large number of small urban centres in the region. A question that needs to be asked is whether such small centres were characteristic of the Deccan. A corollary to this would be whether there were large urban centres as well. The answer to both questions would be ‘yes’. Given the geography of the Deccan, there were a large number of smaller centres that can be identified. Sources from Maharashtra, for example, refer to kasbas(qasbas), peths and mire. Kasbas were understood to be places that had a permanent market. Thus, an urban centre could have both a kasba (a permanent market) and a peth (a local or semi-permanent market) within it.