The Core and the Periphery: a Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century Author(S): Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Banaras: a City of Cultural and Economic Dynamics and Response

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT. – DEC. 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Medieval Banaras: A City of Cultural and Economic Dynamics and Response Pritam Kumar Gupta Research Scholar, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Received: November 12, 2018 Accepted: December 17, 2018 ABSTRACT This paper attempts to understand the cultural and economic importance of the city of Banarasto various medieval political powers.As there are many examples on the basis of which it can be said that the nature, dynamics, and popularity of a city have changed at different times according to the demands and needs of the time. Banaras is one of those ancient cities which has been associated with various religious beliefs and cultures since ancient times but the city, while retaining its old features, established itself as a developed trade city by accepting new economic challenges, how the Banaras provided a suitable environment to the changing cultural and economic challenges, whereas it went through the pressure of different political powers from time to time and made them realize its importance. This paper attempts to understand those suitable environmentson how the landscape of Banaras and its dynamics in the medieval period transformed this city into a developed economic-cultural city. Keywords: Banaras, Religious, Economic, Urbanization, Mughal, Market, Landscape. Wide-ranging literary works have been written on Banaras by scholars of various subject backgrounds, in which they highlight the socio-economic life of different religious and cultural ideals of the inhabitants of Banaras. It is very important for scholars studying regional history to understand what challenges a city has to face in different historical periods to maintain its identity.The name Banaras is found as the present name Varanasi in the Buddhist Jataka and Hindu epic Mahabharata. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

The Aaj Ka Dhamaka Edition November 1, 2014

MONSOON The Aaj Ka Dhamaka Edition November 1, 2014 00000 MONSOON ISSUE 1 OUR SPONSORS Carolina Asia Center with the support of the U.S. Department of Edu- cation Center for Global Initiatives UNC Sangam YFund through the Campus Y OUR TEAM Editors: Anisha Padma and Parth Shah Writers: Snigdha Das, Debanjali Kundu, Alekhya Mallavarapu, Dinesh McCoy, Pranati Panuganti, Hinal Patel, Maitreyee Singh, Nikhil Umesh, Soumya Vishwanath, and Naintara Viswanath Photographers: Hamid Ali, Amanda Betner, Arpan Bhandari, Snigdha Das, Aribah Shah, Megha Singh, and Soumya Vishwanath Website Design: Sara Khan Publicity: Ranjitha Ananthan and Iti Madan Magazine Design: Sara Khan and Shruti Patel Contributors: Andrew Ashley, Kane Borders, Mr. John Caldwell, Sarvani Gandhavadi, Dr. Iqbal Sevea, and Dr. Afroz Taj 1 LETTER FROM THE EDITORS Social media has sparked a renaissance of new ideas. Facebook news feeds and Twitter timelines are constantly flooded with photos, videos and articles concerning both local and global issues. UNC Monsoon aims to ride this wave and produce marketable online and print content that brings South Asian voices to the forefront. Prior to Monsoon, UNC Sangam sponsored Diaspora, a campus magazine devoted to South Asian affairs. However, we felt that Diaspora was in need of a rebranding in its mission and name. Monsoon’s mission is to creatively foster dialogue about all eight South Asian countries: Ban- gladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal, Maldives, Afghanistan, and Bhutan. It seeks to fight both the misrepresentation and underrepresentation of South Asia in mainstream media by producing original content that informs, entertains, and also fosters discussion. The problem UNC Monsoon addresses is the symbolic annihilation of South Asians by the mainstream media. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Central Administration of Akbar

Central Administration of Akbar The mughal rule is distinguished by the establishment of a stable government and other social and cultural activities. The arts of life flourished. It was an age of profound change, seemingly not very apparent on the surface but it definitely shaped and molded the socio economic life of our country. Since Akbar was anxious to evolve a national culture and a national outlook, he encouraged and initiated policies in religious, political and cultural spheres which were calculated to broaden the outlook of his contemporaries and infuse in them the consciousness of belonging to one culture. Akbar prided himself unjustly upon being the author of most of his measures by saying that he was grateful to God that he had found no capable minister, otherwise people would have given the minister the credit for the emperor’s measures, yet there is ample evidence to show that Akbar benefited greatly from the council of able administrators.1 He conceded that a monarch should not himself undertake duties that may be performed by his subjects, he did not do to this for reasons of administrative efficiency, but because “the errors of others it is his part to remedy, but his own lapses, who may correct ?2 The Mughal’s were able to create the such position and functions of the emperor in the popular mind, an image which stands out clearly not only in historical and either literature of the period but also in folklore which exists even today in form of popular stories narrated in the villages of the areas that constituted the Mughal’s vast dominions when his power had not declined .The emperor was looked upon as the father of people whose function it was to protect the weak and average the persecuted. -

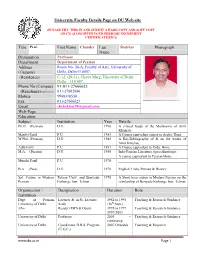

Title Prof. First Name Chander Last Name Photograph Designation

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND SUBMIT A HARD COPY AND SOFT COPY ON CD ALONGWITH YOUR PERIODIC INCREMENT CERTIFICATE(PIC)) Title Prof. First Name Chander Last Shekhar Photograph Name Designation Professor Department Department of Persian Address Room No- 58-A, Faculty of Arts, University of (Campus) Delhi, Delhi-110007. (Residence) C-12, (29-31), Chatra Marg, University of Delhi Delhi – 110 007. Phone No (Campus) 91-011-27666623 (Residence)optional 011-27662086 Mobile 9968318530 Fax 011-27666623 Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. (Persian) D.U. 1990 A critical Study of the Mathnawis of Amir Khusrau. Maulvi Fazil P.U. 1983 A Course equivalent course to Arabic Hons. M.Phil. (Persian) D.U. 1982 A Bio-Bibliography of & on the works of Amir Khusrau Adib Fazil P.U 1981 A Course equivalent to Urdu. Hons. M.A. (Persian) D.U. 1980 Indo-Persian Literature.(specialization)s A course equivalent to Persian Hons. Munshi Fazil P.U 1978 B.A. (Pass) D.U.. 1978 English. Urdu, Persian & History Spl. Course in Modern Tehran Univ. and Bonyade- 1978 A Short term course in Modern Persian on the Persian Farhange Iran, Tehran scholarship of Bonyade Farhange Iran, Tehran Organisation / Designation Duration Role Institution Dept. of Persian, Lecturer & in Sr. Lecturer 1982 to 1995 Teaching & Research Guidance University of Delhi Scale (16th Sept.) -Do- Reader (MPS & Open) 1995 to 1997 Teaching & Research Guidance 1997-2003 University of Delhi Professor 2003 – Teaching & Research Guidance continuing University of Delhi Coordinator D.R.S. -

Temple Destruction and the Great Mughals' Religious

Analisa Journal of Social Science and Religion Website Journal : http://blasemarang.kemenag.go.id/journal/index.php/analisa DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18784/analisa.v3i1.595 TEMPLE DESTRUCTION AND THE GREAT MUGHALS’ RELIGIOUS POLICY IN NORTH INDIA: A Case Study of Banaras Region, 1526-1707 Parvez Alam Department of History, ABSTRACT Banaras Hindu University, Banaras also known as Varanasi (at present a district of Uttar Pradesh state, India) Varanasi, India, 221005 [email protected] was a sarkar (district) under Allahabad Subah (province) during the great Mughals period (1526-1707). The great Mughals have immortal position for their contribu- Paper received: 07 February 2018 tions to Indian economic, society and culture, most important in the development of Paper revised: 15 – 23 May 2018 Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb (Hindustani culture). With the establishment of their state in Paper approved: 11 July 2018 Northern India, Mughal emperors had effected changes by their policies. One of them was their religious policy which is a very controversial topic though is very impor- tant to the history of medieval India. There are debates among the historians about it. According to one group, Mughals’ religious policy was very intolerance towards non- Muslims and their holy places, while the opposite group does not agree with it, and say that Mughlas adopted a liberal religious policy which was in favour of non-Mus- lims and their deities. In the context of Banaras we see the second view. As far as the destruction of temples is concerned was not the result of Mughals’ bigotry, but due to the contemporary political and social circumstances. -

CAN the REIGN of SHAH JAHAN BE CALLED the GOLDEN ERA of INDIAN HISTORY? *Mr

C S CAN THE REIGN OF SHAH JAHAN BE CALLED THE GOLDEN ERA OF INDIAN HISTORY? *Mr. Ashutosh Audichya & **Dr. Anshul Sharma **PhD Scholar, Himalayan University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh, India. **Head & Assistant Professor, Department of History, S.S Jain Subodh .P.G College, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. ABSTRACT: Emperor Shah Jahan was one of the greatest Mughal Emperors of India. He ruled an empire that was as vast as the Roman Empire and the British Empire. It covered today’s India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan and parts of Iran. Shah Jahan during his reign built up a strong army that ensured that he ruled one of the largest empires in the history of the world. Mewar, which was a hostile kingdom for centuries submitted to Mughal dominance. It was during Shah Jahan’s time that the south Indian kingdoms like Ahmednagar, Bijapur and Golcoonda also submitted to the Mughal dominance. During this period some of the world’s most beautiful pieces of art and architecture were built up like the Red Fort of Delhi, the Taj Mahal of Agra, the famous peacock throne etc. Financial collections of the Empire rose to the highest level during this period. This was a phase of Indian history which was by and large peaceful and progressive. But in spite of this, this period has been painted in black by many historians. Extravagant lifestyle of the Emperor, huge expenses for promoting art and architecture, too much pressure exerted on subjects for payment of taxes, increasing corruption levels of the army and the royal executive were reasons that created a severe financial recession immediately after the reign of Shah Jahan ended. -

The Merchant Castes of a Small Town in Rajasthan

THE MERCHANT CASTES OF A SMALL TOWN IN RAJASTHAN (a study of business organisation and ideology) CHRISTINE MARGARET COTTAM A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. at the Department of Anthropology and Soci ology, School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. ProQuest Number: 10672862 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672862 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT Certain recent studies of South Asian entrepreneurial acti vity have suggested that customary social and cultural const raints have prevented positive response to economic develop ment programmes. Constraints including the conservative mentality of the traditional merchant castes, over-attention to custom, ritual and status and the prevalence of the joint family in management structures have been regarded as the main inhibitors of rational economic behaviour, leading to the conclusion that externally-directed development pro grammes cannot be successful without changes in ideology and behaviour. A focus upon the indigenous concepts of the traditional merchant castes of a market town in Rajasthan and their role in organising business behaviour, suggests that the social and cultural factors inhibiting positivejto a presen ted economic opportunity, stimulated in part by external, public sector agencies, are conversely responsible for the dynamism of private enterprise which attracted the attention of the concerned authorities. -

Azad Kashmir

Azad Kashmir The home of British Kashmiris Waving flags of their countries of origin by some members of diaspora (overseas) communities in public space is one of the most common and visible expressions of their ‘other’ or ‘homeland’ identity or identities. In Britain, the South Asian diaspora communities are usually perceived as Indian, Pakistani, (since 1971) Bangladeshis and Sri Lankans. However, there is another flag that is sometimes sighted on such public gatherings as Eid festivals, Pakistani/Indian Cricket Matches or political protests across Britain. 1 This is the official flag of the government of Azad Jammu and Kashmir. 'Azad Kashmir' is a part of the divided state of Jammu Kashmir. Its future is yet to be determined along with rest of the state. As explained below in detail, Azad Kashmir is administered by Pakistan but it is not part of Pakistan like Punjab, Sindh, Pakhtoon Khuwa and Baluchistan. However, as a result of the invasion of India and Pakistan to capture Kashmir in October 1947 and the subsequent involvement of United Nations, Pakistan is responsible for the development and service provision including passports for the people of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit Baltistan, another part of Kashmir that is not part of, but is controlled by, Pakistan. Under the same UN resolutions India is responsible for the Indian controlled part of Kashmir. In all parts of the divided Kashmir there are political movements of different intensity striving for greater rights and autonomy, self-rule and/or independence. The focus of this chapter, however, is primarily on Azad Kashmir, the home of nearly a million strong British Kashmiri community. -

Economy of Transport in Mughal India

ECONOMY OF TRANSPORT IN MUGHAL INDIA ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Bottor of ^t)tla£foplip ><HISTORY S^r-A^. fi NAZER AZIZ ANJUM % 'i A ^'^ -'mtm''- kWgj i. '* y '' «* Under the Supervision of PROFESSOR SHIREEN MOOSVI CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 4LIGARH (INDIA) 2010 ABSTRACT ]n Mughal India land revenue (which was about 50% of total produce) was mainly realised in cash and this resulted in giving rise to induced trade in agricultural produce. The urban population of Mughal India was over 15% of the total population - much higher than the urban population in 1881(i.e.9.3%). The Mughal ruling class were largely town-based. At the same time foreign trade was on its rise. Certain towns were emerging as a centre of specialised manufactures. These centres needed raw materials from far and near places. For example, Ahmadabad in Gujarat a well known centre for manufacturing brocade, received silk Irom Bengal. Saltpeter was brought from Patna and indigo from Biana and adjoining regions and textiles from Agra, Lucknow, Banaras, Gazipur to the Gujarat ports for export. This meant development of long distance trade as well. The brisk trade depended on the conditions and techniques of transport. A study of the economy of transport in Mughal India is therefore an important aspect of Mughal economy. Some work in the field has already been done on different aspects of system of transport in Mughal India. This thesis attempts a single study bringing all the various aspects of economy of transport together.