Medieval Banaras: a City of Cultural and Economic Dynamics and Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

The Core and the Periphery: a Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century Author(S): Z

Social Scientist The Core and the Periphery: A Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century Author(s): Z. U. Malik Source: Social Scientist, Vol. 18, No. 11/12 (Nov. - Dec., 1990), pp. 3-35 Published by: Social Scientist Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3517149 Accessed: 03-04-2020 15:29 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Social Scientist is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Scientist This content downloaded from 117.240.50.232 on Fri, 03 Apr 2020 15:29:21 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Z.U. MALIK* The Core and the Periphery: A Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century** There is a general unanimity among modern historians on seeing the dissolution of Mughal empire as a notable phenomenon cf the eighteenth century. The discord of views relates to the classification and explanation of historical processes behind it, and also to the interpretation and articulation of its impact on political and socio- economic conditions of the country. Most historians sought to explain the imperial crisis from the angle of medieval society in general, relating it to the character and quality of people, and the roles of the diverse classes. -

Central Administration of Akbar

Central Administration of Akbar The mughal rule is distinguished by the establishment of a stable government and other social and cultural activities. The arts of life flourished. It was an age of profound change, seemingly not very apparent on the surface but it definitely shaped and molded the socio economic life of our country. Since Akbar was anxious to evolve a national culture and a national outlook, he encouraged and initiated policies in religious, political and cultural spheres which were calculated to broaden the outlook of his contemporaries and infuse in them the consciousness of belonging to one culture. Akbar prided himself unjustly upon being the author of most of his measures by saying that he was grateful to God that he had found no capable minister, otherwise people would have given the minister the credit for the emperor’s measures, yet there is ample evidence to show that Akbar benefited greatly from the council of able administrators.1 He conceded that a monarch should not himself undertake duties that may be performed by his subjects, he did not do to this for reasons of administrative efficiency, but because “the errors of others it is his part to remedy, but his own lapses, who may correct ?2 The Mughal’s were able to create the such position and functions of the emperor in the popular mind, an image which stands out clearly not only in historical and either literature of the period but also in folklore which exists even today in form of popular stories narrated in the villages of the areas that constituted the Mughal’s vast dominions when his power had not declined .The emperor was looked upon as the father of people whose function it was to protect the weak and average the persecuted. -

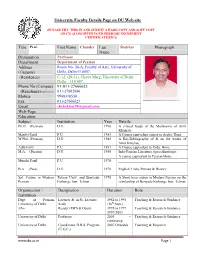

Title Prof. First Name Chander Last Name Photograph Designation

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND SUBMIT A HARD COPY AND SOFT COPY ON CD ALONGWITH YOUR PERIODIC INCREMENT CERTIFICATE(PIC)) Title Prof. First Name Chander Last Shekhar Photograph Name Designation Professor Department Department of Persian Address Room No- 58-A, Faculty of Arts, University of (Campus) Delhi, Delhi-110007. (Residence) C-12, (29-31), Chatra Marg, University of Delhi Delhi – 110 007. Phone No (Campus) 91-011-27666623 (Residence)optional 011-27662086 Mobile 9968318530 Fax 011-27666623 Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. (Persian) D.U. 1990 A critical Study of the Mathnawis of Amir Khusrau. Maulvi Fazil P.U. 1983 A Course equivalent course to Arabic Hons. M.Phil. (Persian) D.U. 1982 A Bio-Bibliography of & on the works of Amir Khusrau Adib Fazil P.U 1981 A Course equivalent to Urdu. Hons. M.A. (Persian) D.U. 1980 Indo-Persian Literature.(specialization)s A course equivalent to Persian Hons. Munshi Fazil P.U 1978 B.A. (Pass) D.U.. 1978 English. Urdu, Persian & History Spl. Course in Modern Tehran Univ. and Bonyade- 1978 A Short term course in Modern Persian on the Persian Farhange Iran, Tehran scholarship of Bonyade Farhange Iran, Tehran Organisation / Designation Duration Role Institution Dept. of Persian, Lecturer & in Sr. Lecturer 1982 to 1995 Teaching & Research Guidance University of Delhi Scale (16th Sept.) -Do- Reader (MPS & Open) 1995 to 1997 Teaching & Research Guidance 1997-2003 University of Delhi Professor 2003 – Teaching & Research Guidance continuing University of Delhi Coordinator D.R.S. -

Temple Destruction and the Great Mughals' Religious

Analisa Journal of Social Science and Religion Website Journal : http://blasemarang.kemenag.go.id/journal/index.php/analisa DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18784/analisa.v3i1.595 TEMPLE DESTRUCTION AND THE GREAT MUGHALS’ RELIGIOUS POLICY IN NORTH INDIA: A Case Study of Banaras Region, 1526-1707 Parvez Alam Department of History, ABSTRACT Banaras Hindu University, Banaras also known as Varanasi (at present a district of Uttar Pradesh state, India) Varanasi, India, 221005 [email protected] was a sarkar (district) under Allahabad Subah (province) during the great Mughals period (1526-1707). The great Mughals have immortal position for their contribu- Paper received: 07 February 2018 tions to Indian economic, society and culture, most important in the development of Paper revised: 15 – 23 May 2018 Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb (Hindustani culture). With the establishment of their state in Paper approved: 11 July 2018 Northern India, Mughal emperors had effected changes by their policies. One of them was their religious policy which is a very controversial topic though is very impor- tant to the history of medieval India. There are debates among the historians about it. According to one group, Mughals’ religious policy was very intolerance towards non- Muslims and their holy places, while the opposite group does not agree with it, and say that Mughlas adopted a liberal religious policy which was in favour of non-Mus- lims and their deities. In the context of Banaras we see the second view. As far as the destruction of temples is concerned was not the result of Mughals’ bigotry, but due to the contemporary political and social circumstances. -

CAN the REIGN of SHAH JAHAN BE CALLED the GOLDEN ERA of INDIAN HISTORY? *Mr

C S CAN THE REIGN OF SHAH JAHAN BE CALLED THE GOLDEN ERA OF INDIAN HISTORY? *Mr. Ashutosh Audichya & **Dr. Anshul Sharma **PhD Scholar, Himalayan University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh, India. **Head & Assistant Professor, Department of History, S.S Jain Subodh .P.G College, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. ABSTRACT: Emperor Shah Jahan was one of the greatest Mughal Emperors of India. He ruled an empire that was as vast as the Roman Empire and the British Empire. It covered today’s India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan and parts of Iran. Shah Jahan during his reign built up a strong army that ensured that he ruled one of the largest empires in the history of the world. Mewar, which was a hostile kingdom for centuries submitted to Mughal dominance. It was during Shah Jahan’s time that the south Indian kingdoms like Ahmednagar, Bijapur and Golcoonda also submitted to the Mughal dominance. During this period some of the world’s most beautiful pieces of art and architecture were built up like the Red Fort of Delhi, the Taj Mahal of Agra, the famous peacock throne etc. Financial collections of the Empire rose to the highest level during this period. This was a phase of Indian history which was by and large peaceful and progressive. But in spite of this, this period has been painted in black by many historians. Extravagant lifestyle of the Emperor, huge expenses for promoting art and architecture, too much pressure exerted on subjects for payment of taxes, increasing corruption levels of the army and the royal executive were reasons that created a severe financial recession immediately after the reign of Shah Jahan ended. -

Economy of Transport in Mughal India

ECONOMY OF TRANSPORT IN MUGHAL INDIA ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Bottor of ^t)tla£foplip ><HISTORY S^r-A^. fi NAZER AZIZ ANJUM % 'i A ^'^ -'mtm''- kWgj i. '* y '' «* Under the Supervision of PROFESSOR SHIREEN MOOSVI CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 4LIGARH (INDIA) 2010 ABSTRACT ]n Mughal India land revenue (which was about 50% of total produce) was mainly realised in cash and this resulted in giving rise to induced trade in agricultural produce. The urban population of Mughal India was over 15% of the total population - much higher than the urban population in 1881(i.e.9.3%). The Mughal ruling class were largely town-based. At the same time foreign trade was on its rise. Certain towns were emerging as a centre of specialised manufactures. These centres needed raw materials from far and near places. For example, Ahmadabad in Gujarat a well known centre for manufacturing brocade, received silk Irom Bengal. Saltpeter was brought from Patna and indigo from Biana and adjoining regions and textiles from Agra, Lucknow, Banaras, Gazipur to the Gujarat ports for export. This meant development of long distance trade as well. The brisk trade depended on the conditions and techniques of transport. A study of the economy of transport in Mughal India is therefore an important aspect of Mughal economy. Some work in the field has already been done on different aspects of system of transport in Mughal India. This thesis attempts a single study bringing all the various aspects of economy of transport together. -

VIKAS RATHEE Department of History Central University of Punjab V.P.O

Rathee cv VIKAS RATHEE Department of History Central University of Punjab V.P.O. Ghudda, District Bathinda, Punjab, INDIA 151401 [email protected] APPOINTMENTS July 2019 – now Assistant Professor, Department of History, School of Social Sciences, Central University of Punjab Nov 2016 – July 2019 Assistant Professor of History, South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab Oct 2014-Sept 2016 PBC Post-doctoral Research Fellow, Harry S. Truman Institute for the Advancement of Peace, Hebrew University of Jerusalem March 2005-March 2006 Guest Lecturer, Dept of Germanic & Romance Studies, University of Delhi Aug 2001 – Jun 2002 Manager (Logistics) & Tour Guide, Aquaterra Adventures (Pvt.) Ltd, Delhi for river and mountain operations in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh. EDUCATION Jan 2007-Aug 2015 Department of History, The University of Arizona Ph.D. in History (Middle Eastern Caucus), for the thesis “Narratives of the 1658 War of Succession for the Mughal Throne, 1658-1707,”. Committee: Richard Eaton (Chair), Linda Darling, Allison Busch (Columbia University) and Brian Silverstein (Anthropology). Minor: World & Comparative History. 2002-2006 Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi, India . M.Phil. in History (CGPA: 7.69 on a scale of 9.0, first division) . Unpublished M.Phil. Dissertation: “Centre and the Region: Aspects of the Making of Mughal Rule in the Bengal Subah, 16th and 17th Centuries” (Advisor: Rajat Datta) . M.A. in History (specialisation - Medieval Indian History, CGPA: 6.56 on a scale of 9.0, First Division), Centre for Historical Studies, School of Social Sciences 1998-2002 St. Stephen's College, University of Delhi, India B.A. -

Unit 21 Agric'ultural Production

.UNIT 21 AGRIC'ULTURAL PRODUCTION. structure 21.0 Objectives 21.1 Introduction 21.2 Extent of Cultivation 21.3 Means of Cultivation and Imgation 21.3.1 Means and Methods of Cultivation 21.3.2 Means of Imgation 21.4 Agricultural Produce 21.4.1 Food Crops 21.4.2 Cash Crops 21.4.3 Fruits, Vegetables and Spices 21.4.4 Productivity and Yields 21.5 Cattle and Livestock 21.6 Let Us Sum Up 21.7 Key Words 21.8 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises This Unit deals with agricultural production in India during the period of this study. After going through this Unit you would have an idea about the extent of cultivation during the period under study; know about the means and methods of cultivation and irrigation; be able.to list the main crops grown; and have some idea about the status of livestock and cattle breeding. 21.1 INTRODUCTION India has a very large land area with diverse climatic zones. Throughout its history, agriculture has been its predominant productive activity. During the Mughal period, large tracts of land were under the plough. Contemporary Indian and foreign writers praise the fertility of Indian soil. In this Unit, we will discuss many aspects including the extent of cultivation, that is the land under plough. A wide rangdof food crops, fruits, vegetables and crop were grown in India. However, we would take a stock only of the main crop grown during this period. We will also discuss the methods of cultivation as also the implements used for cultivation and irrigation technology. -

In Size but Invariably in a Position Proving Them to Be Retreating Baffled and Beaten, Were Intended to Represent the Asuras, Po

1110 NOTICES OF BOORS in size but invariably in a position proving them to be retreating baffled and beaten, were intended to represent the Asuras, powers of darkness and evil, humbled by and retiring before the presence of the life-giving deity. From my own point of view the most serious mistake in the book is to be found in the note to vol. i, p. 126, where the author, of course by pure accident, does me the entirely undeserved honour of attributing to me the authorship of Mr. Vincent Smith's Fine Art in India. The error is much to be regretted. R. SEWELL. CATALOGUE OF COINS IN THE PANJAB MUSEUM, LAHORE. By R. B. WHITEHEAD. Oxford, 1914. (Continued from the July Part, p. 795.) The second volume of this Catalogue deals with the coins of the Mughal Emperors of India, an important series which until recent times has not received adequate attention from numismatists. The revival of interest in the subject may be said to date from the publication of the British Museum Catalogue in 1892 and from the researches of Mr. C. J. Rodgers in the Panjab. The British Museum cabinet then contained about 1,250 coins, a number now greatly increased. The recent activity in this branch of numismatics may be measured by the fact that the Indian Museum at Calcutta, which contained 863 Mughal coins in 1894, contained 2,560 when Mr. Nelson Wright's Catalogue was issued in 1908, and the Lahore cabinet catalogued by Mr. C. J. Rodgers in 1892, and consisting mainly of his own collection, contained 1,559 Mughal coins, whereas the present Catalogue shows 3,283, the greatest number published as yet in any catalogue. -

India from 16Th Century to Mid-18Th Century

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology India from 16th Century to Mid 18th Century Subject: INDIA FROM 16TH CENTURY TO MID 18TH CENTURY Credits: 4 SYLLABUS India in the 16th Century The Trading World of Asia and the Coming of the Portuguese, Polity and Economy in Deccan and South India, Polity and Economy in North India, Political Formations in Central and West Asia Mughal Empire: Polity and Regional Powers Relations with Central Asia and Persia, Expansion and Consolidation: 1556-1707, Growth of Mughal Empire: 1526-1556, The Deccan States and the Mughals, Rise of the Marathas in the 17th Century, Rajput States, Ahmednagar, Bijapur and Golkonda Political Ideas and Institutions Mughal Administration: Mansab and Jagir, Mughal Administration: Central, Provincial and Local, Mughal Ruling Class, Mughal Theory of Sovereignty State and Economy Mughal Land Revenue System, Agrarian Relations: Mughal India, Land Revenue System: Maratha, Deccan and South India, Agrarian Relations: Deccan and South India, Fiscal and Monetary System, Prices Production and Trade The European Trading Companies, Personnel of Trade and Commercial Practices, Inland and Foreign Trade Non-Agricultural Production, Agricultural Production Society and Culture Population in Mughal India, Rural Classes and Life-style, Urbanization, Urban Classes and Life-style Religious Ideas and Movements, State and Religion, Painting and Fine Arts, Architecture, Science and Technology, Indian Languages and Literature India at the Mid 18th Century Potentialities of Economic Growth: An Overview, Rise of Regional Powers, Decline of the Mughal Empire Suggested Readings 1. -

Suba of Delhi Under the Mughals 1580-1719

SUBA OF DELHI UNDER THE MUGHALS 1580-1719 ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE Ph. D. DEGREE By ABHA SINGH SUPERVISOR : PROFESSOR IRFAN HABIB CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY IN HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 1988 ., ^N^ A2AD _ ABSTRACT ,^^r ^^^ ^^ ^ • % The thesis alms at studying varfoui?^ €!^9nondc; jiolitical and administrative aspects of the Mughal province of Delhi from 1580 to I7l9. Introduction gives the sources on which the thesis is based. All kinds of material, notably Persian historical works and records of ell kinds; Raj asthan! documents and accounts of European travellers have been used. The stud/ begins by establishing the limits of the euba, as well as of its divisions/ and the changes made in them from time to time, ^he physical geography of the area is then studied, with special reference to rainfall lines Cisohyets). An element of human geography alters by correlat ing Mughal administrative boundaries with the linguistic boundaries (after Griereon). An actual correspondence between administrative and linguistic boundaries has not however been established. (Chapter I). Chapter II deals with the pattern of Agricultural production in the suba. It has been found that the extent of cultivation increased greatly between the reigns of Akbar and Aurangzeb. Price variations are also been discussed. The price-data suggests that there wasaxise in the value of wheat between 1595 and 1715. - 2 - Data on mineral productions and manufactures (&3De brought together in Chapter III. This is followed by an analysis of the Land-revenue system in the guba. A comparison of dastur-rates, with Sher shah's rai* and modern yields has been attempted.