Azad Kashmir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V. Aravindakshan 2.Xlsx

അക്സഷ ന് ഗര്ന്ഥകാരന് ഗര്ന്ഥനാമം പര്സാധകന് പതിപ്പ് വര്ഷംഏട്വിലവിഷയം/കല്ാസ്സ് നമ്പര് നമ്പര് 1 Dennis Kavnagh A Dictionary of Political Biography Newyork: Oxford 1998 523 475 320.092 DIC /ARA 2 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 1 Newyork: Oxford 1988 307 4.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 3 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 2 Newyork: Oxford 1987 276 3.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 4 Jelena Stepanova Frederick Engels Moscow: Foreign Language 1958 270 923.343 ENG/ ARA 5 Miriam Schneir The Vintage Book of Feminism Newyork: Vintage 1995 505 7.99 £ 305.42 VIN/ ARA 6 Matriliny Transformed -Family, Law and Ideology in K. Saradamoni Twenteth century Travancore New Delhi: Sage 1 1999 176 175 306.83 SAR/ARA 7 Lumpenbourgeoisle: Lumpendevelopment- Andre Gunder Frank Dependence, class and politics in Latin America Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 128 80 320.9 FRA/ ARA 8 Joan Green Baun Windows on the workplace Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 170 100 651.59 GRA/ARA 9 Hridayakumari. E. Vallathol Narayanan Menon New Delhi: CSA 2 1982 91 4 894.812 109 HRD/ ARA 10 George. K.M. Kumaran Asan New Delhi: CSA 2 1984 96 4 894.812 109 GEO/ ARA Page 1 11 Tharakan. K.M. M.P. Paul New Delhi: CSA 1 1985 96 4 894.812 109 THA/ ARA 12 335.43 AJI/ARA Ajit Roy Euro-Communism' An Analytical story Calcutta: Pearl 88 10 13 801.951 MAC/ARA Archi Bald Macleish Poetry and Experience Australia: Penguin Books 1960 187 Alien Homage' -Edward Thompson and 14 891.4414 THO/ARA E.P. Thompson Rabindranath Tagore New Delhi : Oxford 2 1998 175 275 15 894.812309 VIS/ARA R.Viswanathan Pottekkatt New Delhi: CSA 1 1998 60 5 16 891.73 CHE/ARA A.P. -

June Ank 2016

The Specter of Emergency Continues to Haunt the Country Mahi Pal Singh Forty one years ago this country witnessed people had been detained without trial under the the darkest chapter in the history of indepen- repressive Maintenance of Internal Security Act dent and democratic India when the state of (MISA), several high courts had given relief to emergency was proclaimed on the midnight of the detainees by accepting their right to life and 25th-26th June 1975 by Indira Gandhi, the then personal liberty granted under Article 21 and ac- Prime Minister of the country, only to satisfy cepting their writs for habeas corpus as per pow- her lust for power. The emergency was declared ers granted to them under Article 226 of the In- when Justice Jagmohanlal Sinha of the dian constitution. This issue was at the heart of Allahabad High Court invalidated her election the case of the Additional District Magistrate of to the Lok Sabha in June 1975, upholding Jabalpur v. Shiv Kant Shukla, popularly known charges of electoral fraud, in the case filed by as the Habeas Corpus case, which came up for Raj Narain, her rival candidate. The logical fol- hearing in front of the Supreme Court in Decem- low up action in any democratic country should ber 1975. Given the important nature of the case, have been for the Prime Minister indicted in the a bench comprising the five senior-most judges case to resign. Instead, she chose to impose was convened to hear the case. emergency in the country, suspend fundamen- During the arguments, Justice H.R. -

Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy

Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy July 18, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45818 SUMMARY R45818 Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy July 18, 2019 Afghanistan has been a significant U.S. foreign policy concern since 2001, when the United States, in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, led a military Clayton Thomas campaign against Al Qaeda and the Taliban government that harbored and supported it. Analyst in Middle Eastern In the intervening 18 years, the United States has suffered approximately 2,400 military Affairs fatalities in Afghanistan, with the cost of military operations reaching nearly $750 billion. Congress has appropriated approximately $133 billion for reconstruction. In that time, an elected Afghan government has replaced the Taliban, and most measures of human development have improved, although Afghanistan’s future prospects remain mixed in light of the country’s ongoing violent conflict and political contention. Topics covered in this report include: Security dynamics. U.S. and Afghan forces, along with international partners, combat a Taliban insurgency that is, by many measures, in a stronger military position now than at any point since 2001. Many observers assess that a full-scale U.S. withdrawal would lead to the collapse of the Afghan government and perhaps even the reestablishment of Taliban control over most of the country. Taliban insurgents operate alongside, and in periodic competition with, an array of other armed groups, including regional affiliates of Al Qaeda (a longtime Taliban ally) and the Islamic State (a Taliban foe and increasing focus of U.S. policy). U.S. -

Jammu and Kashmir Directorate of Information Accredited Media List (Jammu) 2017-18 S

Government of Jammu and Kashmir Directorate of Information Accredited Media List (Jammu) 2017-18 S. Name & designation C. No Agency Contact No. Photo No Representing Correspondent 1 Mr. Gopal Sachar J- Hind Samachar 01912542265 Correspondent 236 01912544066 2 Mr. Arun Joshi J- The Tribune 9419180918 Regional Editor 237 3 Mr. Zorawar Singh J- Freelance 9419442233 Correspondent 238 4 Mr. Ashok Pahalwan J- Scoop News In 9419180968 Correspondent 239 0191-2544343 5 Mr. Suresh.S. Duggar J- Hindustan Hindi 9419180946 Correspondent 240 6 Mr. Anil Bhat J- PTI 9419181907 Correspondent 241 7 S. Satnam Singh J- Dainik Jagran 941911973701 Correspondent 242 91-2457175 8 Mr. Ajaat Jamwal J- The Political & 9419187468 Correspondent 243 Business daily 9 Mr. Mohit Kandhari J- The Pioneer, 9419116663 Correspondent 244 Jammu 0191-2463099 10 Mr. Uday Bhaskar J- Dainik Bhaskar 9419186296 Correspondent 245 11 Mr. Ravi Krishnan J- Hindustan Times 9419138781 Khajuria 246 7006506990 Principal Correspondent 12 Mr. Sanjeev Pargal J- Daily Excelsior 9419180969 Bureau Chief 247 0191-2537055 13 Mr. Neeraj Rohmetra J- Daily Excelsior 9419180804 Executive Editor 248 0191-2537901 14 Mr. J. Gopal Sharma J- Daily Excelsior 9419180803 Special Correspondent 249 0191-2537055 15 Mr. D. N. Zutshi J- Free-lance 88035655773 250 16 Mr. Vivek Sharma J- State Times 9419196153 Correspondent 251 17 Mr. Rajendra Arora J- JK Channel 9419191840 Correspondent 252 18 Mr. Amrik Singh J- Dainik Kashmir 9419630078 Correspondent 253 Times 0191-2543676 19 Ms. Suchismita J- Kashmir Times 9906047132 Correspondent 254 20 Mr. Surinder Sagar J- Kashmir Times 9419104503 Correspondent 255 21 Mr. V. P. Khajuria J- J. N. -

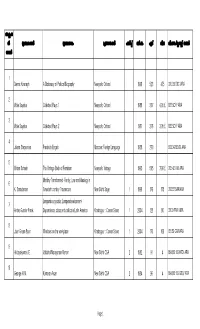

Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.No Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID

Details of Employees (Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID Women Medical 1 Dr. Afroze Khan Muhammad Chang (NULL) (NULL) Officer Women Medical 2 Dr. Shahnaz Abdullah Memon (NULL) 4130137928800 (NULL) Officer Muhammad Yaqoob Lund Women Medical 3 Dr. Saira Parveen (NULL) 4130379142244 (NULL) Baloch Officer Women Medical 4 Dr. Sharmeen Ashfaque Ashfaque Ahmed (NULL) 4140586538660 (NULL) Officer 5 Sameera Haider Ali Haider Jalbani Counselor (NULL) 4230152125668 214483656 Women Medical 6 Dr. Kanwal Gul Pirbho Mal Tarbani (NULL) 4320303150438 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 7 Dr. Saiqa Parveen Nizamuddin Khoso (NULL) 432068166602- (NULL) Officer Tertiary Care Manager 8 Faiz Ali Mangi Muhammad Achar (NULL) 4330213367251 214483652 /Medical Officer Women Medical 9 Dr. Kaneez Kalsoom Ghulam Hussain Dobal (NULL) 4410190742003 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 10 Dr. Sheeza Khan Muhammad Shahid Khan Pathan (NULL) 4420445717090 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 11 Dr. Rukhsana Khatoon Muhammad Alam Metlo (NULL) 4520492840334 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 12 Dr. Andleeb Liaqat Ali Arain (NULL) 454023016900 (NULL) Officer Badin S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID 1 MUHAMMAD SHAFI ABDULLAH WATER MAN unknown 1350353237435 10334485 2 IQBAL AHMED MEMON ALI MUHMMED MEMON Senior Medical Officer unknown 4110101265785 10337156 3 MENZOOR AHMED ABDUL REHAMN MEMON Medical Officer unknown 4110101388725 10337138 4 ALLAH BUX ABDUL KARIM Dispensor unknown -

Afzal Guru's Execution

Contents ARTICLES - India’s Compass On Terror Is Faulty What Does The Chinese Take Over - Kanwal Sibal 3 Of Gwadar Imply? 46 Stop Appeasing Pakistan - Radhakrishna Rao 6 - Satish Chandra Reforming The Criminal Justice 103 Slandering The Indian Army System 51 10 - PP Shukla - Dr. N Manoharan 107 Hydro Power Projects Race To Tap The ‘Indophobia’ And Its Expressions Potential Of Brahmaputra River 15 - Dr. Anirban Ganguly 62 - Brig (retd) Vinod Anand Pakistan Looks To Increase Its Defence Acquisition: Urgent Need For Defence Footprint In Afghanistan Structural Reforms 21 - Monish Gulati 69 - Brig (retd) Gurmeet Kanwal Political Impasse Over The The Governor , The Constitution And The Caretaker Government In 76 Courts 25 Bangladesh - Dr M N Buch - Neha Mehta Indian Budget Plays With Fiscal Fire 34 - Ananth Nageswaran EVENTS Afzal Guru’s Execution: Propaganda, Politics And Portents 41 Vimarsha: Security Implications Of - Sushant Sareen Contemporary Political 80 Environment In India VIVEK : Issues and Options March – 2013 Issue: II No: III 2 India’s Compass On Terror Is Faulty - Kanwal Sibal fzal Guru’s hanging shows state actors outside any law. The the ineptness with which numbers involved are small and A our political system deals the targets are unsuspecting and with the grave problem of unprepared individuals in the terrorism. The biggest challenge to street, in public transport, hotels our security, and indeed that of or restaurants or peaceful public countries all over the world that spaces. Suicide bombers and car are caught in the cross currents of bombs can cause substantial religious extremism, is terrorism. casualties indiscriminately. Shadowy groups with leaders in Traditional military threats can be hiding orchestrate these attacks. -

Ian Salisbury (England 1992 to 2001) Ian Salisbury Was a Prolific Wicket

Ian Salisbury (England 1992 to 2001) Ian Salisbury was a prolific wicket-taker in county cricket but struggled in his day job in Tests, taking only 20 wickets at large expense. Wisden claimed the leg-spinner’s googly could be picked because of a higher arm action, which negated the threat he posed. Keith Medlycott, his Surrey coach, felt Salisbury was under-bowled and had his confidence diminished by frequent criticism from people who had little understanding of a leggie’s travails. Yet Ian was a willing performer and an excellent tourist. Salisbury’s Test career was a stop-start affair. Over more than eight years, he played in only 15 Tests. Despite these disappointments Salisbury’s determination was never in doubt. Several times as well, he showed more backbone than his supposedly superior English spin colleagues; most notably in India in early 1993. Ian Salisbury also proved to be an excellent nightwatchman, invariably making useful contributions. His Test innings as nightwatchman are shown below. Date Opponents Venue In Out Minutes Score Jun 1992 Pakistan Lord’s 40-1 73-2 58 12 Jan 1993 India Calcutta 87-5 163 AO 183 28 Mar 1994 West Indies Georgetown 253-5 281-7 86 8 Mar 1994 West Indies Trinidad 26-5 27-6 6 0 Jul 1994 South Africa Lord’s 136-6 59 6* Aug 1996 Pakistan Oval 273-6 283-7 27 5 Jul 1998 South Africa Nottingham 199-4 244-5 102 23 Aug 1998 South Africa Leeds 200-4 206-5 21 4 Nov 2000 Pakistan Lahore 391-6 468-8 148 31 Nov 2000 Pakistan Faisalabad 105-2 203-4 209 33 Ian Salisbury’s NWM Appearances in Test matches Salisbury had only one failure as a Test match nightwatchman; joining his fellow rabbits in Curtly Ambrose’s headlights in the rout for 46 in Trinidad. -

AJK at a Glance 2009

1 2 3 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO General Azad Jammu and Kashmir lies between longitude 730 - 750 and latitude of 33o - 36o and comprises of an area of 5134 Square Miles (13297 Square Kilometers). The topography of the area is mainly hilly and mountainous with valleys and stretches of plains. Azad Kashmir is bestowed with natural beauty having thick forests, fast flowing rivers and winding streams, main rivers are Jehlum, Neelum and Poonch. The climate is sub-tropical highland type with an average yearly rainfall of 1300 mm. The elevation from sea level ranges from 360 meters in the south to 6325 meters in the north. The snow line in winter is around 1200 meters above sea level while in summer, it rises to 3300 meters. According to the 1998 population census the state of Azad Jammu & Kashmir had a population of 2.973 million, which is estimated to have grown to 3.868 million in 2009. Almost 100% population comprises of Muslims. The Rural: urban population ratio is 88:12. The population density is 291 persons per Sq. Km. Literacy rate which was 55% in 1998 census has now raised to 64%. Approximately the infant mortality rate is 56 per 1000 live births, whereas the immunization rate for the children under 5 years of age is more than 95%. The majority of the rural population depends on forestry, livestock, agriculture and non- formal employment to eke out its subsistence. Average per capita income has been estimated to be 1042 US$*. Unemployment ranges from 6.0 to 6.5%. In line with the National trends, indicators of social sector particularly health and population have not shown much proficiency. -

The Constitution and Female-Initiated Divorce in Pakistan: Western Liberalism in Islamic Garb

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLG\34-2\HLG207.txt unknown Seq: 1 13-JUN-11 8:12 THE CONSTITUTION AND FEMALE-INITIATED DIVORCE IN PAKISTAN: WESTERN LIBERALISM IN ISLAMIC GARB KARIN CARMIT YEFET* “[N]o nation can ever be worthy of its existence that cannot take its women along with the men.” Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Founder of Pakistan1 The legal status of Muslim women, especially in family relations, has been the subject of considerable international academic and media interest. This Article examines the legal regulation of di- vorce in Pakistan, with particular attention to the impact of the nation’s dual constitutional commitments to gender equality and Islamic law. It identifies the right to marital freedom as a constitu- tional right in Pakistan and demonstrates that in a country in which women’s rights are notoriously and brutally violated, female di- vorce rights stand as a ray of light amidst the “darkness” of the general legal status of Pakistani women. Contrary to the conven- tional wisdom construing Islamic law as opposed to women’s rights, the constitutionalization of Islam in Pakistan has proven to be a potent tool in the service of women’s interests. Ultimately, I hope that this Article may serve as a model for the utilization of both Islamic and constitutional law to benefit women throughout the Muslim world. Introduction .................................................... 554 R I. All-or-Nothing: Classical Islam’s Gendered Divorce Regime ................................................. 557 R A. The Husband’s Right to Untie the Knot ............... 558 R * I wish to express my deep gratitude to Professors Akhil Reed Amar and Reva Siegel for their thoughtful and inspiring comments. -

From Insurgency to Militancy to Terrorism. by Balraj Puri* in 1989, A

BALRAJ PURI Kashmir's Journey: From insurgency to militancy to terrorism. by Balraj Puri* * Director of the Institute of Jammu and Kashmir Affairs – Karan Nagar – Jammu – India In 1989, a massive Muslim insurgency erupted in Kashmir. A number of internal and external factors were responsible for it. Among them, was the "Rajiv-Farooq" accord towards the end of 1986, by virtue of which Farooq Abdullah, dismissed from power two years earlier, was brought back to power as interim chief minister (1987) after a deal with the Congress party. By vacating his role as the principal pro-India opposition leader, Farooq left the Muslim United Front, the first party based on a religious identity, as the only outlet for popular discontent. As the assembly election of 1987 had been rigged to facilitate his return to power, the people felt that there was no democratic outlet left to vent their discontent. Externally, the break up of the Soviet block where one satellite country after the other in East Europe got independence following protest demonstrations, was also a source of inspiration for the people of Kashmir who at last believed that "azadi" (azadi in Urdu or Farsi means personal liberty. Its first political connotation among the people has become, without a doubt, representative democracy) was round the corner if they followed the East Europe example. Furthermore, not far away, as the Soviet forces had pulled out from Afghanistan, harassed and vanquished by the Taliban who had the support of USA and of Pakistan, armed and trained Mujahids involved in that struggle became available and were diverted to Kashmir to support the local insurgency. -

The First National Conference Government in Jammu and Kashmir, 1948-53

THE FIRST NATIONAL CONFERENCE GOVERNMENT IN JAMMU AND KASHMIR, 1948-53 THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN HISTORY BY SAFEER AHMAD BHAT Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ISHRAT ALAM CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2019 CANDIDATE’S DECLARATION I, Safeer Ahmad Bhat, Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, certify that the work embodied in this Ph.D. thesis is my own bonafide work carried out by me under the supervision of Prof. Ishrat Alam at Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. The matter embodied in this Ph.D. thesis has not been submitted for the award of any other degree. I declare that I have faithfully acknowledged, given credit to and referred to the researchers wherever their works have been cited in the text and the body of the thesis. I further certify that I have not willfully lifted up some other’s work, para, text, data, result, etc. reported in the journals, books, magazines, reports, dissertations, theses, etc., or available at web-sites and included them in this Ph.D. thesis and cited as my own work. The manuscript has been subjected to plagiarism check by Urkund software. Date: ………………… (Signature of the candidate) (Name of the candidate) Certificate from the Supervisor Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University This is to certify that the above statement made by the candidate is correct to the best of my knowledge. Prof. Ishrat Alam Professor, CAS, Department of History, AMU (Signature of the Chairman of the Department with seal) COURSE/COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION/PRE- SUBMISSION SEMINAR COMPLETION CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. -

11848041 01.Pdf

Report Organization This report consists of the following volumes: Final Report I Volume 1 : Summary Volume 2 : Main Report Volume 3 : Sector Report Final Report II Urgent Rehabilitation Projects In Final Report I, volume 1 Summary contains the outline of the results of the study. Volume 2 Main Report contains the Master Plan for rehabilitation and reconstruction in Muzaffarabad city, Pakistan. Volume 3 Sector Report contains the details of existing conditions, issues to overcome, and proposals for future reconstruction by sector. Final Report II deals with the results and outcomes on the Urgent Rehabilitation Projects which were prioritized and implemented in parallel with master plan formulation work under the supervision of JICA Study Team. The exchange rate applied in the Study is: (Pakistan Rupee) (Japanese Yen) Rs.1 = ¥1.91 (Pakistan Rupee) (US Dollar) Rs.60.30 = US$ 1 PREFACE In response to the request from the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, the Government of Japan decided to conduct a Urgent Development Study on Rehabilitation and Reconstruction in Muzaffarabad City in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and entrusted the Study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched the Study Team headed by Mr. Ichiro Kobayashi of Pacet, consisted of Pacet and Nippon Koei, to the Islamic Republic of Pakistan from February 2006 to August 2006. JICA set up an Advisory Committee chaired by Dr. Kazuo Konagai from the University of Tokyo, which examined the study from the specialist and technical points of view. The Study Team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and conducted the Study in collaboration with the Pakistani counterparts.