ABSTRACT SUBAH of KASHI^IIR UNDER the Nughals WITH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) Hazratbal, Srinagar, Kashmir, J&K, India-190006 No

University of Kashmir Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) Hazratbal, Srinagar, Kashmir, J&K, India-190006 No. F (CBCS -Basket-Review)198/20. Dated: 14.09.2020 NOTICE Sub:- Review of Course Baskets of PG 3rd Sem (2019 Batch) and PG 4th Sem (2018 Batch). All the Heads of the Departments/Directors of Satellite Campuses/Principals of PG Colleges/Coordinators of PG Programmes are asked to direct the concerned Academic Counsellors (ACs) to review the departmental Courses (Core, DCE, GE and OE) in Course-baskets of PG 3rd Sem (2019 Batch) and PG 4th Sem (2018 Batch). The course baskets for both the semesters are available under “CBCS” tab in the footer portion of the University’s Main Website. The same have also been directly emailed to Academic Counsellors for ready reference and review In case of any inconsistency, deficiency or error, kindly revert back to us on this email ([email protected]) or phone (7889665644) latest by Sept 20, 2020. Sd/- Chief Coordinator CBCS Copy to: 1. The Heads of the Departments/Directors of Satellite Campuses/Principals of PG Colleges/Coordinators of PG Programmes 2. PA to Dean Academic Affairs for information to Dean Academic Affairs. 3. File. 4th Sem 2019 COURSECODE SUBJECTCODE SUBJECTNAME CREDITS Capacity Timing BMFA FA18001OE Outdoor/Open Air Landscape/Acrylic/Water Colour/Oil Colour 2 0 0 BMFA FA18002OE Creative Painting, Basic Fundamentals 2 0 0 BMFA FA178003OE Creative Photography 2 0 0 BMFA FA18004OE Clay Modelling 2 0 0 BMFA FA18005OE Indian Classical(Vocal) 2 0 0 BMFA FA18006OE Indian Classical(Sitar) 2 -

Medieval Banaras: a City of Cultural and Economic Dynamics and Response

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT. – DEC. 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Medieval Banaras: A City of Cultural and Economic Dynamics and Response Pritam Kumar Gupta Research Scholar, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Received: November 12, 2018 Accepted: December 17, 2018 ABSTRACT This paper attempts to understand the cultural and economic importance of the city of Banarasto various medieval political powers.As there are many examples on the basis of which it can be said that the nature, dynamics, and popularity of a city have changed at different times according to the demands and needs of the time. Banaras is one of those ancient cities which has been associated with various religious beliefs and cultures since ancient times but the city, while retaining its old features, established itself as a developed trade city by accepting new economic challenges, how the Banaras provided a suitable environment to the changing cultural and economic challenges, whereas it went through the pressure of different political powers from time to time and made them realize its importance. This paper attempts to understand those suitable environmentson how the landscape of Banaras and its dynamics in the medieval period transformed this city into a developed economic-cultural city. Keywords: Banaras, Religious, Economic, Urbanization, Mughal, Market, Landscape. Wide-ranging literary works have been written on Banaras by scholars of various subject backgrounds, in which they highlight the socio-economic life of different religious and cultural ideals of the inhabitants of Banaras. It is very important for scholars studying regional history to understand what challenges a city has to face in different historical periods to maintain its identity.The name Banaras is found as the present name Varanasi in the Buddhist Jataka and Hindu epic Mahabharata. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

Miss Farhat Jabeen

Some Aspects of the Sociai History of the Valley of Kashmir during the period 1846—1947'-Customs and Habits By: lUEblS Miss Farhat Jabeen Thesis Submitted for the award of i Doctor of Philosophy ( PH. D.) Post Graduate Department of History THE: UNIVERSITY OF KASHAIIR ^RXNJf.GA.R -190006 T5240 Thl4 is to certify that the Ph.D. thesis of Miss Far hat JabeiA entitled "Some Aspects of the Social History of tha Valley of Kashnir during the period 1846.-1947— Cus^ms and Habits*• carried out under my supervision embodies the work of the candidate. The research vork is of original nature and has not been submlt-ted for a Ph.D. degree so far« It is also certified that the scholar has put in required I attendance in the Department of History* University of Kashmir, The thesis is in satisfactory literary form and worthy of consideration for a Ph.D. degree* SUPERVISOR '»•*•« $#^$7M7«^;i«$;i^ !• G, R, *** General Records 2. JSdC ••• Jammu and Kashmir 3, C. M, S. ••» Christian Missionary Society 4. Valley ••* The Valley of Kashmir 5. Govt. **i* Government 6, M.S/M.S.S *** ManuscriptAlenuscripts, 7. NOs Number 8, P. Page 9, Ed. ••• Edition, y-itU 10. K.T. *•• Kashmir Today 11. f.n* •••f Foot Note 12» Vol, ••• Volume 13. Rev, •*• Revised 14. ff/f **• VniiosAolio 15, Deptt. *** Department 16. ACC *** Accession 17. Tr, *** Translated 18. Blk *** Bikrand. ^v^s^s ^£!^mmmSSSmSSimSSSmS^lSSmSm^^ ACKNOWL EDGEMENTt This Study was undertaken in the year 1985) December, as a research project for ny Ph.D. programme under the able guidance of Dr. -

The Core and the Periphery: a Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century Author(S): Z

Social Scientist The Core and the Periphery: A Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century Author(s): Z. U. Malik Source: Social Scientist, Vol. 18, No. 11/12 (Nov. - Dec., 1990), pp. 3-35 Published by: Social Scientist Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3517149 Accessed: 03-04-2020 15:29 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Social Scientist is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Scientist This content downloaded from 117.240.50.232 on Fri, 03 Apr 2020 15:29:21 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Z.U. MALIK* The Core and the Periphery: A Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century** There is a general unanimity among modern historians on seeing the dissolution of Mughal empire as a notable phenomenon cf the eighteenth century. The discord of views relates to the classification and explanation of historical processes behind it, and also to the interpretation and articulation of its impact on political and socio- economic conditions of the country. Most historians sought to explain the imperial crisis from the angle of medieval society in general, relating it to the character and quality of people, and the roles of the diverse classes. -

Rare Collection About Kashmir: Survey and Documentation

RARE COLLECTION ABOUT KASHMIR: SURVEY AND DOCUMENTATION Rosy Jan Shahina Islam Uzma Qadri Department of Library and Information Science University of Kashmir India ABSTRACT Kashmir has been a fascinating subject for authors and analysts. Volumes have been documented and published about its multi-faceted aspects in varied forms like manuscripts, rare books and images available in a number of institutions, libraries and museums worldwide. The study explores the institutions and libraries worldwide possessing rare books (published before 1920) about Kashmir using online survey method and documents their bibliographical details. The study aims to analyze subject, chronology and country wise collection strength. The study shows that the maximum collection of the rare books is on travelogue 32.48% followed by Shaivism1 8.7%. While as the collection on other subjects lies in the range of 2.54%-5.53% with least of 2.54% on Grammar. Literature of 20th century is preserved by maximum of libraries (53.89%) followed by 19th century (44.93%), 18th century (1.08%) and 17th century (0.09%) and none of the library except Cambridge University library possesses a publication of 17th century. The treasure of rare books lies maximum in United States of America (56.7%) followed by Great Britain (35%), Canada(6%), Australia (1.8%) with least in Thailand (0.45%). Keywords: Rare Books; Rare Books Collections; Kashmir; Manuscripts; Paintings. 1 INTROUCTION Kashmir has been a center of attraction for philosophers and litterateurs, beauty seekers and people of different interests from centuries. It is not only because of the scenic beauty of its snow caped mountain ranges, myriad lakes, changing hues of majestic china’s and crystal clear springs but also because of its rich cultural heritage and contribution to Philosophy, Religion, Literature, Art and Craft (KAW, 50 BJIS, Marília (SP), v.6, n.1, p.50-61, Jan./Jun. -

Central Administration of Akbar

Central Administration of Akbar The mughal rule is distinguished by the establishment of a stable government and other social and cultural activities. The arts of life flourished. It was an age of profound change, seemingly not very apparent on the surface but it definitely shaped and molded the socio economic life of our country. Since Akbar was anxious to evolve a national culture and a national outlook, he encouraged and initiated policies in religious, political and cultural spheres which were calculated to broaden the outlook of his contemporaries and infuse in them the consciousness of belonging to one culture. Akbar prided himself unjustly upon being the author of most of his measures by saying that he was grateful to God that he had found no capable minister, otherwise people would have given the minister the credit for the emperor’s measures, yet there is ample evidence to show that Akbar benefited greatly from the council of able administrators.1 He conceded that a monarch should not himself undertake duties that may be performed by his subjects, he did not do to this for reasons of administrative efficiency, but because “the errors of others it is his part to remedy, but his own lapses, who may correct ?2 The Mughal’s were able to create the such position and functions of the emperor in the popular mind, an image which stands out clearly not only in historical and either literature of the period but also in folklore which exists even today in form of popular stories narrated in the villages of the areas that constituted the Mughal’s vast dominions when his power had not declined .The emperor was looked upon as the father of people whose function it was to protect the weak and average the persecuted. -

Page5.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU WEDNESDAY, MAY 14, 2014 (PAGE 5) Govt silent as paddy land VC KU, Dr Hajini, Prof Ravi call on Vohra Excelsior Correspondent activities in the University and, and preserving the Kashmiri Medical Education, Research as desired by the Chancellor, language and culture. and Training Programme in a shrinks at alarming rate SRINAGAR, May 13: Prof. gave him a list of all significant The Governor appreciated meeting with in Vohra informed Mir Iqbal under apple crop was 1, 40,156 Talat Ahmad, Vice Chancellor, matters which would require to the role of the AMK in high- him that he along with Dr. Dewa hectares which has increased to University of Kashmir, called on be decided in the coming weeks. lighting the rich culture, tradi- Ramlu, Vice President, SRINAGAR, May 13: The 1, 43,534 hectares in 2013-14. Governor N.N Vohra, Dr. Aziz Hajini, President, tions and literature of Kashmir International University, School agriculture land is shrinking at Despite High Court's direc- Chancellor of the University, Adbee Markaz Kamraz (AMK) and wished Dr. Hajini high suc- Of Medicine, Michigan, USA an alarming rate in Kashmir val- tions to Government for impos- here at Raj Bhavan today. also called on Mr. Vohra and cess in all the future endeavors would like to assist the Shri The Vice Chancellor briefed briefed him about pursuits of of the Kamraz. Amarnath ji Shrine Board and CEO of SMVDSB addressing at a seminar on Drugs ley, particularly in south ing a blanket ban on raising con- the Governor about the to date AMK in collection and publica- Prof. -

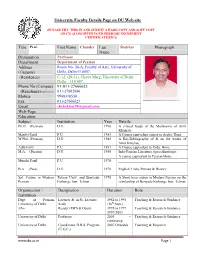

Title Prof. First Name Chander Last Name Photograph Designation

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND SUBMIT A HARD COPY AND SOFT COPY ON CD ALONGWITH YOUR PERIODIC INCREMENT CERTIFICATE(PIC)) Title Prof. First Name Chander Last Shekhar Photograph Name Designation Professor Department Department of Persian Address Room No- 58-A, Faculty of Arts, University of (Campus) Delhi, Delhi-110007. (Residence) C-12, (29-31), Chatra Marg, University of Delhi Delhi – 110 007. Phone No (Campus) 91-011-27666623 (Residence)optional 011-27662086 Mobile 9968318530 Fax 011-27666623 Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. (Persian) D.U. 1990 A critical Study of the Mathnawis of Amir Khusrau. Maulvi Fazil P.U. 1983 A Course equivalent course to Arabic Hons. M.Phil. (Persian) D.U. 1982 A Bio-Bibliography of & on the works of Amir Khusrau Adib Fazil P.U 1981 A Course equivalent to Urdu. Hons. M.A. (Persian) D.U. 1980 Indo-Persian Literature.(specialization)s A course equivalent to Persian Hons. Munshi Fazil P.U 1978 B.A. (Pass) D.U.. 1978 English. Urdu, Persian & History Spl. Course in Modern Tehran Univ. and Bonyade- 1978 A Short term course in Modern Persian on the Persian Farhange Iran, Tehran scholarship of Bonyade Farhange Iran, Tehran Organisation / Designation Duration Role Institution Dept. of Persian, Lecturer & in Sr. Lecturer 1982 to 1995 Teaching & Research Guidance University of Delhi Scale (16th Sept.) -Do- Reader (MPS & Open) 1995 to 1997 Teaching & Research Guidance 1997-2003 University of Delhi Professor 2003 – Teaching & Research Guidance continuing University of Delhi Coordinator D.R.S. -

Temple Destruction and the Great Mughals' Religious

Analisa Journal of Social Science and Religion Website Journal : http://blasemarang.kemenag.go.id/journal/index.php/analisa DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18784/analisa.v3i1.595 TEMPLE DESTRUCTION AND THE GREAT MUGHALS’ RELIGIOUS POLICY IN NORTH INDIA: A Case Study of Banaras Region, 1526-1707 Parvez Alam Department of History, ABSTRACT Banaras Hindu University, Banaras also known as Varanasi (at present a district of Uttar Pradesh state, India) Varanasi, India, 221005 [email protected] was a sarkar (district) under Allahabad Subah (province) during the great Mughals period (1526-1707). The great Mughals have immortal position for their contribu- Paper received: 07 February 2018 tions to Indian economic, society and culture, most important in the development of Paper revised: 15 – 23 May 2018 Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb (Hindustani culture). With the establishment of their state in Paper approved: 11 July 2018 Northern India, Mughal emperors had effected changes by their policies. One of them was their religious policy which is a very controversial topic though is very impor- tant to the history of medieval India. There are debates among the historians about it. According to one group, Mughals’ religious policy was very intolerance towards non- Muslims and their holy places, while the opposite group does not agree with it, and say that Mughlas adopted a liberal religious policy which was in favour of non-Mus- lims and their deities. In the context of Banaras we see the second view. As far as the destruction of temples is concerned was not the result of Mughals’ bigotry, but due to the contemporary political and social circumstances. -

CAN the REIGN of SHAH JAHAN BE CALLED the GOLDEN ERA of INDIAN HISTORY? *Mr

C S CAN THE REIGN OF SHAH JAHAN BE CALLED THE GOLDEN ERA OF INDIAN HISTORY? *Mr. Ashutosh Audichya & **Dr. Anshul Sharma **PhD Scholar, Himalayan University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh, India. **Head & Assistant Professor, Department of History, S.S Jain Subodh .P.G College, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. ABSTRACT: Emperor Shah Jahan was one of the greatest Mughal Emperors of India. He ruled an empire that was as vast as the Roman Empire and the British Empire. It covered today’s India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan and parts of Iran. Shah Jahan during his reign built up a strong army that ensured that he ruled one of the largest empires in the history of the world. Mewar, which was a hostile kingdom for centuries submitted to Mughal dominance. It was during Shah Jahan’s time that the south Indian kingdoms like Ahmednagar, Bijapur and Golcoonda also submitted to the Mughal dominance. During this period some of the world’s most beautiful pieces of art and architecture were built up like the Red Fort of Delhi, the Taj Mahal of Agra, the famous peacock throne etc. Financial collections of the Empire rose to the highest level during this period. This was a phase of Indian history which was by and large peaceful and progressive. But in spite of this, this period has been painted in black by many historians. Extravagant lifestyle of the Emperor, huge expenses for promoting art and architecture, too much pressure exerted on subjects for payment of taxes, increasing corruption levels of the army and the royal executive were reasons that created a severe financial recession immediately after the reign of Shah Jahan ended. -

Economy of Transport in Mughal India

ECONOMY OF TRANSPORT IN MUGHAL INDIA ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Bottor of ^t)tla£foplip ><HISTORY S^r-A^. fi NAZER AZIZ ANJUM % 'i A ^'^ -'mtm''- kWgj i. '* y '' «* Under the Supervision of PROFESSOR SHIREEN MOOSVI CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 4LIGARH (INDIA) 2010 ABSTRACT ]n Mughal India land revenue (which was about 50% of total produce) was mainly realised in cash and this resulted in giving rise to induced trade in agricultural produce. The urban population of Mughal India was over 15% of the total population - much higher than the urban population in 1881(i.e.9.3%). The Mughal ruling class were largely town-based. At the same time foreign trade was on its rise. Certain towns were emerging as a centre of specialised manufactures. These centres needed raw materials from far and near places. For example, Ahmadabad in Gujarat a well known centre for manufacturing brocade, received silk Irom Bengal. Saltpeter was brought from Patna and indigo from Biana and adjoining regions and textiles from Agra, Lucknow, Banaras, Gazipur to the Gujarat ports for export. This meant development of long distance trade as well. The brisk trade depended on the conditions and techniques of transport. A study of the economy of transport in Mughal India is therefore an important aspect of Mughal economy. Some work in the field has already been done on different aspects of system of transport in Mughal India. This thesis attempts a single study bringing all the various aspects of economy of transport together.