Mh=Nin A!Eide, Qea&, Phlhi+A &Dew 0A Xilhõj Odyssey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Views of the Qin Instructor: Anthony Barbieri-Low Tuesdays, 9:00Am-11:50 Am Office: HSSB 4225 Location: HSSB 2252 Office Hours: Mon

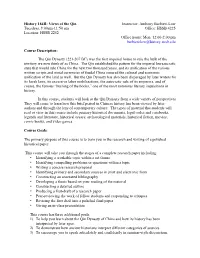

History 184R: Views of the Qin Instructor: Anthony Barbieri-Low Tuesdays, 9:00am-11:50 am Office: HSSB 4225 Location: HSSB 2252 Office hours: Mon. 12:00-2:00 pm [email protected] Course Description: The Qin Dynasty (221-207 BC) was the first imperial house to rule the bulk of the territory we now think of as China. The Qin established the pattern for the imperial bureaucratic state that would rule China for the next two thousand years, and its unification of the various written scripts and metal currencies of feudal China ensured the cultural and economic unification of the land as well. But the Qin Dynasty has also been disparaged by later writers for its harsh laws, its excessive labor mobilizations, the autocratic rule of its emperors, and of course, the famous “burning of the books,” one of the most notorious literary inquisitions in history. In this course, students will look at the Qin Dynasty from a wide variety of perspectives. They will come to learn how this brief period in Chinese history has been viewed by later authors and through the lens of contemporary culture. The types of material that students will read or view in this course include primary historical documents, legal codes and casebooks, legends and literature, historical essays, archaeological materials, historical fiction, movies, comic books, and video games. Course Goals: The primary purpose of this course is to train you in the research and writing of a polished historical paper. This course will take you through the stages of a complete research paper -

Audible Punctuation Performative Pause In

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/140838 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-25 and may be subject to change. AUDIBLE PUNCTUATION Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Audible Punctuation: Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. Th.L.M. Engelen, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 21 mei 2015 om 14.30 uur precies door Ronald Blankenborg geboren op 23 maart 1971 te Eibergen Promotoren: Prof. dr. A.P.M.H. Lardinois Prof. dr. J.B. Lidov (City University New York, Verenigde Staten) Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. M.G.M. van der Poel Prof. dr. E.J. Bakker (Yale University, Verenigde Staten) Prof. dr. M. Janse (Universiteit Gent, België) Copyright©Ronald Blankenborg 2015 ISBN 978-90-823119-1-4 [email protected] [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Printed by Maarse Printing Cover by Gijs de Reus Audible Punctuation: Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Doctoral Thesis to obtain the degree of doctor from Radboud University Nijmegen on the authority of the Rector Magnificus prof. -

U.S. EPA, Pesticide Product Label, CIC RESIDUAL PRESSURIZED

.-!:. NANE OF PESTICIDE PRODUCT NOTICE OF PESTICIDE: o ftEGISTRATION o M:EREGUTRATION (Under the Federal Insecticide, Fun~/"ide. CIC Residual Pressurized and Rodcnlicidt· A d. a:>: amended) Spray No. 1 NAME AND ADDRESS OF REGISTRANT ({ndudo ZIP code) r Coulst.on International Corporation 1'.0. Box 3lJ-' Palmer, I'A lH043 L NOTE: Changes in labeling formula difrering in substance (rom that accepted in connection wilh this registration must be submitted to and accepted by the Registration Division prior to use of the label in commerce. tn any correspondence on this product alwsys refer to the ahove U.S. EPA registration number. On the basis of inCormalion furnished by the registrant, the above named pesticide is hereby Registered/Reregistered under the FederallnsecUcide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act. A copy of the labeling accepted in connection with this Registration/Reregistration is returned herewith. Registration is in no way to be construed as an indorsement or approval d this product by this Agency. In order to protect health and the environment, the Administrator, on his motion, may at any time suspend or cancel the registration of a pest icide in accordance with the Act. The acceptance of any name in connection with the registration of a product under this Act is not to be construed as giving the registrant a right 10 exclusive use of the name or to its use if it has been covered by others. '£his product is conditionally rt!gisterl!d in accordance .... ith FU'RA seeth:n 3(e)(7)(A) provided that you: 1. Submit and/or ci te all data required for registration/reregistration of your preduct under PIFRA section 3(c)(S) when the Agency requires all registrants of similar products to submit such data. -

AFRICA in CHINA's FOREIGN POLICY

AFRICA in CHINA’S FOREIGN POLICY YUN SUN April 2014 Yun Sun is a fellow at the East Asia Program of the Henry L. Stimson Center. NOTE: This paper was produced during the author’s visiting fellowship with the John L. Thornton China Center and the Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings. ABOUT THE JOHN L. THORNTON CHINA CENTER: The John L. Thornton China Center provides cutting-edge research, analysis, dialogue and publications that focus on China’s emergence and the implications of this for the United States, China’s neighbors and the rest of the world. Scholars at the China Center address a wide range of critical issues related to China’s modernization, including China’s foreign, economic and trade policies and its domestic challenges. In 2006 the Brookings Institution also launched the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy, a partnership between Brookings and China’s Tsinghua University in Beijing that seeks to produce high quality and high impact policy research in areas of fundamental importance for China’s development and for U.S.-China relations. ABOUT THE AFRICA GROWTH INITIATIVE: The Africa Growth Initiative brings together African scholars to provide policymakers with high-quality research, expertise and innovative solutions that promote Africa’s economic development. The initiative also collaborates with research partners in the region to raise the African voice in global policy debates on Africa. Its mission is to deliver research from an African perspective that informs sound policy, creating sustained economic growth and development for the people of Africa. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: I would like to express my gratitude to the many people who saw me through this paper; to all those who generously provided their insights, advice and comments throughout the research and writing process; and to those who assisted me in the research trips and in the editing, proofreading and design of this paper. -

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China with a Focus on the Dao

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China With a focus on the Dao An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty Of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE By: Bryan Benson Ryan Coran Alberto Ramirez Date: 04/27/2017 Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados Mr. Tom H. Thomsen 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 List of Figures 4 Individual Participation 7 Authorship 8 1. Abstract 10 2. Introduction 11 3. Historical Background 12 3.1 Fall of Han dynasty/ Formation of the Three Kingdoms 12 3.2 Wu 13 3.3 Shu 14 3.4 Wei 16 3.5 Warfare and Relations between the Three Kingdoms 17 3.5.1 Wu and the South 17 3.5.2 Shu-Han 17 3.5.3 Wei and the Sima family 18 3.6 Weaponry: 18 3.6.1 Four traditional weapons (Qiang, Jian, Gun, Dao) 18 3.6.1.1 The Gun 18 3.6.1.2 The Qiang 19 3.6.1.3 The Jian 20 3.6.1.4 The Dao 21 3.7 Rise of the Empire of Western Jin 22 3.7.1 The Beginning of the Western Jin Empire 22 3.7.2 The Reign of Empress Jia 23 3.7.3 The End of the Western Jin Empire 23 3.7.4 Military Structure in the Western Jin 24 3.8 Period of Disunity 24 4. Materials and Manufacturing During the Period of Disunity 25 2 Table of Contents (Cont.) 4.1 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Han Dynasty 25 4.2 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Period of Disunity 26 5. -

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access China Studies published for the institute for chinese studies, university of oxford Edited by Micah Muscolino (University of Oxford) volume 39 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/chs Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Understanding Chaoben Culture By Ronald Suleski leiden | boston Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover Image: Chaoben Covers. Photo by author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Suleski, Ronald Stanley, author. Title: Daily life for the common people of China, 1850 to 1950 : understanding Chaoben culture / By Ronald Suleski. -

The Warring States Period (453-221)

Indiana University, History G380 – class text readings – Spring 2010 – R. Eno 2.1 THE WARRING STATES PERIOD (453-221) Introduction The Warring States period resembles the Spring and Autumn period in many ways. The multi-state structure of the Chinese cultural sphere continued as before, and most of the major states of the earlier period continued to play key roles. Warfare, as the name of the period implies, continued to be endemic, and the historical chronicles continue to read as a bewildering list of armed conflicts and shifting alliances. In fact, however, the Warring States period was one of dramatic social and political changes. Perhaps the most basic of these changes concerned the ways in which wars were fought. During the Spring and Autumn years, battles were conducted by small groups of chariot-driven patricians. Managing a two-wheeled vehicle over the often uncharted terrain of a battlefield while wielding bow and arrow or sword to deadly effect required years of training, and the number of men who were qualified to lead armies in this way was very limited. Each chariot was accompanied by a group of infantrymen, by rule seventy-two, but usually far fewer, probably closer to ten. Thus a large army in the field, with over a thousand chariots, might consist in total of ten or twenty thousand soldiers. With the population of the major states numbering several millions at this time, such a force could be raised with relative ease by the lords of such states. During the Warring States period, the situation was very different. -

Latin Derivatives Dictionary

Dedication: 3/15/05 I dedicate this collection to my friends Orville and Evelyn Brynelson and my parents George and Marion Greenwald. I especially thank James Steckel, Barbara Zbikowski, Gustavo Betancourt, and Joshua Ellis, colleagues and computer experts extraordinaire, for their invaluable assistance. Kathy Hart, MUHS librarian, was most helpful in suggesting sources. I further thank Gaylan DuBose, Ed Long, Hugh Himwich, Susan Schearer, Gardy Warren, and Kaye Warren for their encouragement and advice. My former students and now Classics professors Daniel Curley and Anthony Hollingsworth also deserve mention for their advice, assistance, and friendship. My student Michael Kocorowski encouraged and provoked me into beginning this dictionary. Certamen players Michael Fleisch, James Ruel, Jeff Tudor, and Ryan Thom were inspirations. Sue Smith provided advice. James Radtke, James Beaudoin, Richard Hallberg, Sylvester Kreilein, and James Wilkinson assisted with words from modern foreign languages. Without the advice of these and many others this dictionary could not have been compiled. Lastly I thank all my colleagues and students at Marquette University High School who have made my teaching career a joy. Basic sources: American College Dictionary (ACD) American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (AHD) Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (ODEE) Oxford English Dictionary (OCD) Webster’s International Dictionary (eds. 2, 3) (W2, W3) Liddell and Scott (LS) Lewis and Short (LS) Oxford Latin Dictionary (OLD) Schaffer: Greek Derivative Dictionary, Latin Derivative Dictionary In addition many other sources were consulted; numerous etymology texts and readers were helpful. Zeno’s Word Frequency guide assisted in determining the relative importance of words. However, all judgments (and errors) are finally mine. -

Xiaohe Xu CV

1 Xiaohe Xu Curriculum Vitae September 1, 2019 Contact Information Department of Sociology University of Texas at San Antonio One UTSA Circle San Antonio, TX 78249 Phone: (210)458-4570 (office) (210)458-4620 (department) (210)632-9543 (cell) Fax: (210)458-4619 E-mail: [email protected] Education Ph.D. in Sociology (1994), the University of Michigan M.A. in Sociology (1985), Michigan State University B.A. in Philosophy (1982), Sichuan University, PRC Employment Chair, Department of Sociology, the University of Texas at San Antonio, 2013-present Research Affiliate of the Population Studies Center, the University of Michigan, 2010-2014 Professor of Sociology, the University of Texas at San Antonio, 2009-present Adjunct Professor of Sociology, Mississippi State University, 2009-present Professor of Sociology, Mississippi State University, 2003-2009 Director of Sociology Graduate Studies, Mississippi State University, 2004-2009 Beverly B. and Gordon W. Gulmon Dean’s Distinguished Professor, Mississippi State University, 2005- 2007 Associate Professor of Sociology, Mississippi State University, 1999-2003 Research Fellow of the Social Science Research Center, Mississippi State University, 1998-2009 Visiting Professor of Sociology, Sichuan University, PRC, 1999-present Assistant Professor of Sociology, Mississippi State University, 1994-1999 Teaching Assistant, 1990-1994, the University of Michigan Teaching Assistant for Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) Summer Program, 1991-1993, the University of Michigan Lecturer of Sociology, 1985-1988, Sichuan University, PRC Teaching Experience Marriage and Family (undergraduate) Introduction to Social Research (sociology major) Social Research Practice (sociology major) Family in the United States (undergraduate and graduate) Comparative Families I: Families across Cultures (undergraduate and graduate) Comparative Families II: Families across Racial/Ethnic Groups in the U. -

A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture

A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture Edited by Antje Richter LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Acknowledgements ix List of Illustrations xi Abbreviations xiii About the Contributors xiv Introduction: The Study of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture 1 Antje Richter PART 1 Material Aspects of Chinese Letter Writing Culture 1 Reconstructing the Postal Relay System of the Han Period 17 Y. Edmund Lien 2 Letters as Calligraphy Exemplars: The Long and Eventful Life of Yan Zhenqing’s (709–785) Imperial Commissioner Liu Letter 53 Amy McNair 3 Chinese Decorated Letter Papers 97 Suzanne E. Wright 4 Material and Symbolic Economies: Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China 135 Xiaofei Tian PART 2 Contemplating the Genre 5 Letters in the Wen xuan 189 David R. Knechtges 6 Between Letter and Testament: Letters of Familial Admonition in Han and Six Dynasties China 239 Antje Richter For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV vi Contents 7 The Space of Separation: The Early Medieval Tradition of Four-Syllable “Presentation and Response” Poetry 276 Zeb Raft 8 Letters and Memorials in the Early Third Century: The Case of Cao Zhi 307 Robert Joe Cutter 9 Liu Xie’s Institutional Mind: Letters, Administrative Documents, and Political Imagination in Fifth- and Sixth-Century China 331 Pablo Ariel Blitstein 10 Bureaucratic Influences on Letters in Middle Period China: Observations from Manuscript Letters and Literati Discourse 363 Lik Hang Tsui PART 3 Diversity of Content and Style section 1 Informal Letters 11 Private Letter Manuscripts from Early Imperial China 403 Enno Giele 12 Su Shi’s Informal Letters in Literature and Life 475 Ronald Egan 13 The Letter as Artifact of Sentiment and Legal Evidence 508 Janet Theiss 14 Infijinite Variations of Writing and Desire: Love Letters in China and Europe 546 Bonnie S. -

Wendy Yi Xu, Ph.D. 208 Cunz Hall, 1841 Neil Avenue Columbus, OH 43210 651-263-7488 [email protected]

Wendy Yi Xu, Ph.D. 208 Cunz Hall, 1841 Neil Avenue Columbus, OH 43210 651-263-7488 [email protected] https://cph.osu.edu/people/wxu I. EMPLOYMENT AND POSITIONS Assistant Professor September 2013 – present Division of Health Services Management and Policy College of Public Health The Ohio State University Assistant Professor (Courtesy Appointment) April 2019-present Division of General Internal Medicine Department of Internal Medicine College of Medicine The Ohio State University Affiliated Faculty October 2013-present OSU Comprehensive Cancer Center (OSUCCC) Affiliated Faculty October 2013-present OSU Institute for Population Research Research Assistant 2007-2012 Division of Health Policy and Management School of Public Health University of Minnesota II. EDUCATION Ph.D., Health Services Research Policy and Administration 2013 School of Public Health University of Minnesota Twin Cities, MN Dissertation: The Impact of Mandatory Comprehensive Coverage of Preventive Care on Consumers Committee: Bryan Dowd, Stephen Parente, Jean Abraham, John Nyman M.S., Health Services Research Policy and Administration 2010 School of Public Health University of Minnesota Twin Cities, MN B.A., Economics 2006 School of International Trade and Economics University of International Business and Economics Beijing, China 1 Wendy Xu Curriculum Vitae III. RESEARCH A. PEER REVIEWED PUBLICATIONS *indicates graduate students † The Runner-Up Award, THE PAN CHALLENGE: Balancing Moral Hazard, Affordability and Access to Critical Therapies in the Age of Cost Sharing, Patient Access Network Foundation 1. Xu WY, Song C, Li Y, Retchin S. Cost-sharing Disparities for Out-of-Network Care in Adults with Behavioral Health Conditions. Forthcoming: JAMA Network Open 2. Xu WY, Retchin S, Seiber E, Li Y.* Disparities of Health Care Financial Burden under the Affordable Care Act. -

My Tomb Will Be Opened in Eight Hundred Yearsâ•Ž: a New Way Of

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2012 'My Tomb Will Be Opened in Eight Hundred Years’: A New Way of Seeing the Afterlife in Six Dynasties China Jie Shi Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Custom Citation Shi, Jie. 2012. "‘My Tomb Will Be Opened in Eight Hundred Years’: A New Way of Seeing the Afterlife in Six Dynasties China." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 72.2: 117–157. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/82 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shi, Jie. 2012. "‘My Tomb Will Be Opened in Eight Hundred Years’: Another View of the Afterlife in the Six Dynasties China." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 72.2: 117–157. http://doi.org/10.1353/jas.2012.0027 “My Tomb Will Be Opened in Eight Hundred Years”: A New Way of Seeing the Afterlife in Six Dynasties China Jie Shi, University of Chicago Abstract: Jie Shi analyzes the sixth-century epitaph of Prince Shedi Huiluo as both a funerary text and a burial object in order to show that the means of achieving posthumous immortality radically changed during the Six Dynasties. Whereas the Han-dynasty vision of an immortal afterlife counted mainly on the imperishability of the tomb itself, Shedi’s epitaph predicted that the tomb housing it would eventually be ruined.