From Colonial Domination to the Making of the Nation. Ethno-Racial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belize National Sustainable Development Report

UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report Belize National Sustainable Development Report Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries, and Sustainable Development, Belize United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (UNDESA) United Nations Development Program (UNDP) ____________________________________ INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANTS – www.idcbz.net Page | 1 UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Acronyms Acknowledgements 1.0. Belize Context……………………………………………………………………………………5 1.1 Geographical Location………………………………………………………………………5 1.2 Climate………………………………………………………………………………………..5 1.3 Hydrology……………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.4 Population…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.5 Political Context……………………………………………………………………………...7 1.6 Economy……………………………………………………………………………………...7 2.0 Background and Approach………………………………………………………………………….7 3.0 Policy and Institutional Framework for Sustainable Development………………………………8 3.1 National Level………………………………………………………………………………..8 3.2 Multi-Lateral Agreements…………………………………………………………………...9 4.0 Progress to Date in Sustainable Development…………………………………………………..10 5.0 Challenges to Sustainable Development…………………………………………………………23 5.1 Environmental and Social Vulnerabilities………………………………………………..23 5.2 Natural Disasters…………………………………………………………………………...23 5.3 Climate Change…………………………………………………………………………….23 5.4 Economic Vulnerability…………………………………………………………………….24 5.5 Policy and Institutional Challenges……………………………………………………….24 6.0 Opportunities for Sustainable Development……………………………………………………..26 -

A Study of the Garifuna of Belize's Toledo District Alexander Gough

Indigenous identity in a contested land: A study of the Garifuna of Belize’s Toledo district Alexander Gough This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Lancaster University Law School 1 Declaration This thesis has not been submitted in support of an application for another degree at this or any other university. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated. Many of the ideas in this thesis were the product of discussion with my supervisors. Alexander Gough, Lancaster University 21st September 2018 2 Abstract The past fifty years has seen a significant shift in the recognition of indigenous peoples within international law. Once conceptualised as the antithesis to European identity, which in turn facilitated colonial ambitions, the recognition of indigenous identity and responding to indigenous peoples’ demands is now a well-established norm within the international legal system. Furthermore, the recognition of this identity can lead to benefits, such as a stake in controlling valuable resources. However, gaining tangible indigenous recognition remains inherently complex. A key reason for this complexity is that gaining successful recognition as being indigenous is highly dependent upon specific regional, national and local circumstances. Belize is an example of a State whose colonial and post-colonial geographies continue to collide, most notably in its southernmost Toledo district. Aside from remaining the subject of a continued territorial claim from the Republic of Guatemala, in recent years Toledo has also been the battleground for the globally renowned indigenous Maya land rights case. -

The Song of Kriol: a Grammar of the Kriol Language of Belize

The Song of Kriol: A Grammar of the Kriol Language of Belize Ken Decker THE SONG OF KRIOL: A GRAMMAR OF THE KRIOL LANGUAGE OF BELIZE Ken Decker SIL International DIS DA FI WI LANGWIJ Belize Kriol Project This is a publication of the Belize Kriol Project, the language and literacy arm of the National Kriol Council No part of this publication may be altered, and no part may be reproduced in any form without the express permission of the author or of the Belize Kriol Project, with the exception of brief excerpts in articles or reviews or for educational purposes. Please send any comments to: Ken Decker SIL International 7500 West Camp Wisdom Rd. Dallas, TX 75236 e-mail: [email protected] or Belize Kriol Project P.O. Box 2120 Belize City, Belize c/o e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Copies of this and other publications of the Belize Kriol Project may be obtained through the publisher or the Bible Society Bookstore 33 Central American Blvd. Belize City, Belize e-mail: [email protected] © Belize Kriol Project 2005 ISBN # 978-976-95215-2-0 First Published 2005 2nd Edition 2009 Electronic Edition 2013 CONTENTS 1. LANGUAGE IN BELIZE ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 AN INTRODUCTION TO LANGUAGE ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 DEFINING BELIZE KRIOL AND BELIZE CREOLE ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

224 Mavis C. Campbell Assad Shoman

224 book reviews Mavis C. Campbell Becoming Belize: A History of an Outpost of Empire Searching for Identity, 1528–1823. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2011. xxii + 425 pp. (Paper US$50.00) Assad Shoman A History of Belize in Thirteen Chapters. 2nd edition. Belize City: The Angelus Press, 2011. xvii + 461 pp. (Paper US$30.00) Modern Belize is commonly referred to as a Caribbean nation in Central Amer- ica. Geographically part of Central America, its English language use and polit- ical history make it part of the Anglophone Caribbean, which may explain in part its relative neglect by scholars of both regions. While Mavis Campbell is not correct to state that Narda Dodson’s A History of Belize (1973) is “the only comprehensive history of Belize written by a trained historian” (p. xiv), she is certainly right to assert that Belizean history “deserves more attention” (p. 4). The enlarged edition of Assad Shoman’s 1994 history is a new contribution aimed at filling the gap. Becoming Belize adds significantly to our understanding of Belize’s begin- nings. Although Campbell did not investigate Spanish primary sources in Ma- drid and Seville, she consulted archives in Belize and Jamaica, at British insti- tutions, and, briefly, in Mérida. The book’s first section examines Spanish at- tempts at settling Belize, from about 1528 to 1708. Campbell explores why Belize became British, given the region’s history, and revisits early Spanish exploration, including Columbus’s 1502 voyage to the Bay Islands of modernity, when he came closest to Belize, and the 1511 shipwreck that left two Spaniards, Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, in the Yucatán. -

Educating Belize: Challenges and Opportunities for the Future

The University of Texas at Austin IC2 Institute Madison Weigand Dr. David Gibson UT Bridging Disciplines http://ic2.utexas.edu/ z EDUCATING BELIZE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE August 2015 BELIZE IC2 2 “Belize is paying a lot for education but getting little. More youth are outside the school system than in it and many fail to make the transition to the workforce. … Action is needed if Belize is not to lose a whole generation of youth.” - Inter-American Development Bank, “Challenges and Opportunities in the Belize Education Sector”, 2013 Belize: why we’re here Belize is a small nation in Central America, bordered to the north by Mexico, by Guatemala to the west and south, and by the Caribbean Sea to the east. Estimates of the national population vary from 340,000 – 360,0001, with population density averaging at 15 people per square kilometer2. In consideration of these low figures, Belize is often the forgotten nation of the Caribbean region. The small country, approximately the size of the state of Massachusetts, is occasionally omitted on regional maps and periodically has its sovereignty threatened by threats of invasion from the neighboring Guatemalan government (Rodriguez-Boetsch 6). In spite of its status as a sidelined nation, Belize is a haven of natural resources that have long been underestimated and underutilized. The country contains a broad spectrum of ecosystems and environments that lend themselves well to agricultural, fishing, and logging industries, as well as tourism—particularly ecotourism—contributing to the Belizean economy’s heavy dependence upon primary resource extraction and international tourism and trade. -

302232 Travelguide

302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.1> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 5 WELCOME 6 GENERAL VISITOR INFORMATION 8 GETTING TO BELIZE 9 TRAVELING WITHIN BELIZE 10 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 14 CRUISE PASSENGER ADVENTURES Half Day Cultural and Historical Tours Full Day Adventure Tours 16 SUGGESTED OVERNIGHT ADVENTURES Four-Day Itinerary Five-Day Itinerary Six-Day Itinerary Seven-Day Itinerary 25 ISLANDS, BEACHES AND REEF 32 MAYA CITIES AND MYSTIC CAVES 42 PEOPLE AND CULTURE 50 SPECIAL INTERESTS 57 NORTHERN BELIZE 65 NORTH ISLANDS 71 CENTRAL COAST 77 WESTERN BELIZE 87 SOUTHEAST COAST 93 SOUTHERN BELIZE 99 BELIZE REEF 104 HOTEL DIRECTORY 120 TOUR GUIDE DIRECTORY 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.2> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.3> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 The variety of activities is matched by the variety of our people. You will meet Belizeans from many cultural traditions: Mestizo, Creole, Maya and Garifuna. You can sample their varied cuisines and enjoy their music and Belize is one of the few unspoiled places left on Earth, their company. and has something to appeal to everyone. It offers rainforests, ancient Maya cities, tropical islands and the Since we are a small country you will be able to travel longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere. from East to West in just two hours. Or from North to South in only a little over that time. Imagine... your Visit our rainforest to see exotic plants, animals and birds, possible destinations are so accessible that you will get climb to the top of temples where the Maya celebrated the most out of your valuable vacation time. -

The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1966 The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas. Alan Knowlton Craig Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Craig, Alan Knowlton, "The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas." (1966). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1117. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1117 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been „ . „ i i>i j ■ m 66—6437 microfilmed exactly as received CRAIG, Alan Knowlton, 1930— THE GEOGRAPHY OF FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1966 G eo g rap h y University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE GEOGRAPHY OP FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State university and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Alan Knowlton Craig B.S., Louisiana State university, 1958 January, 1966 PLEASE NOTE* Map pages and Plate pages are not original copy. They tend to "curl". Filmed in the best way possible. University Microfilms, Inc. AC KNQWLEDGMENTS The extent to which the objectives of this study have been acomplished is due in large part to the faithful work of Tiburcio Badillo, fisherman and carpenter of Cay Caulker Village, British Honduras. -

Rassegna Stampa Fids

Direzione Marketing e Comunicazione – Ufficio Stampa RASSEGNA STAMPA FIDS Maggio – Dicembre 2019 ANSA http://www.ansa.it/emiliaromagna/notizie/2019/05/15/a-rimini-leuropeo-di-street-dance_304aa318-4e1f- 416c-a968-f3bff0822c45.html Direzione Marketing e Comunicazione FIDS Responsabile: Dionisio Ciccarese per l’Ufficio Stampa Alessandro Montone (333 3911417) Direzione Marketing e Comunicazione – Ufficio Stampa ADNKRONOS BREAKDANCE: EUROPEI A RIMINI DAL 16 AL 19 MAGGIO = Roma, 15 mag. - (AdnKronos) - Rimini si infiamma con le sfide e le battaglie delle Urban Dance. Al Rds Stadium è tutto pronto per l'appuntamento con l'Europeo di Breakdance, Hip Hop e Electric Boogie, promosso dalla Ido (International dance organization) che per quattro giorni, dal 16 al 19 maggio, trasformerà la città romagnola in un vero tempio delle street dance internazionali. Sul dancefloor riminese sono attesi oltre 2.000 atleti, proveniente da 26 Nazioni che si sfideranno in evoluzioni, battle e gare one to one nei cyper e nelle arene tipiche dell'arti di strada. A scendere in pista le categorie Children, Junior e Adult suddivise a loro volta in Solo Male, Solo Female, Duo, Group e Formation che vedranno gareggiare le unità competitive under 11, 12/15 e 16/Oltre. Grande attenzione sarà riservata alle gare di Breakdance degli atleti 12/15 in quanto i migliori potranno andare a formare la nuova nazionale under 18 che potrà partecipare alle selezioni per le Olimpiadi Giovanile che si terranno in Senegal nel 2022. (segue) (Spr/AdnKronos) ISSN 2465 – 122 - 15-MAG-19 12:37 . NNNN BREAKDANCE: EUROPEI A RIMINI DAL 16 AL 19 MAGGIO (2) = (AdnKronos) - La Break sarà inoltre protagonista nella categoria 16/Oltre con i ''Fantastici 4'' della FIDS: Alessandra Cortesia (Bgirl Lexy), Alex Mammì (Bboy Lele), Eleonora Mereu (Bgirl Kobra) e Mattia Schinco (Bboy Bad Matty) che oltre a puntare alla vittoria nell'Europeo riminese comporranno la Nazionale Azzurra che a fine luglio parteciperà al Mondiale di breakdance in Cina. -

“We Are Strong Women”: a Focused Ethnography Of

“WE ARE STRONG WOMEN”: A FOCUSED ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE REPRODUCTIVE LIVES OF WOMEN IN BELIZE Carrie S. Klima, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2002 Belize is a small country in Central America with a unique heritage. The cultural pluralism found in Belize provides an opportunity to explore the cultures of the Maya, Mestizo and the Caribbean. Women in Belize share this cultural heritage as well as the reproductive health issues common to women throughout the developing world. The experiences of unintended pregnancy, contraceptive use and abortion were explored with women using a feminist ethnographic framework. Key informants, participant observations, secondary data sources and individual interviews provided rich sources of data to examine the impact of culture in Belize upon the reproductive lives of women. Data were collected over a two-year period and analyzed using QSRNudist qualitative data analysis software. Analysis revealed that regardless of age, ethnicity or educational background, women who found themselves pregnant prior to marriage experienced marriage as a fundamental cultural norm in Belize. Adolescent pregnancy often resulted in girls’ expulsion from school and an inability to continue with educational goals. Within marriage, unintended pregnancy was accepted but often resulted in more committed use of contraception. All women had some knowledge and experience with contraception, Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Carrie S. Klima-University of Connecticut, 2002 although some were more successful than others in planning their families. Couples usually made decisions together regarding when to use contraception, however misinformation regarding safety and efficacy was prevalent. While abortion is illegal, most women had knowledge of abortion practices and some had personal experiences with self induced abortions using traditional healing practices common in Belize. -

Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize

DEBORAH L. CROOKS / UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize We were once much smarter people. into traditional statistical models of biological anthro- —Maya caretaker at archaeological site, Toledo District, Belize pological research is difficult because of the distinctly different nature of the two kinds of data produced. One MOPAN MAYA CHILDREN of San Antonio, Toledo, Be- approach to this problem is discussed by William lize, face a number of challenges to their success in Dressier (1995), who advocates using ethnography up school. Mayan ethnicity, language, and traditional eco- front in the research design to construct culturally nomic strategies are rendered disadvantageous for meaningful variables that can then be quantified for school achievement by historical, social, cultural, and testing. Resulting models are able to account for local economic forces. Statistics on poverty and child growth levels of meaning within the framework of "scientific" indicate that Mayan children are poorer and more research. poorly nourished than other Belizean children, and they Another approach is that taken by Thomas Leather- do less well on national achievement exams. In addi- man (in press) and Brooke Thomas (in press). This po- tion, they attend school structured on the British model litical-economic approach uses quantitative measures and taught in English. In the past, biocultural ap- of biological outcome but contextualizes the numbers proaches might model a causal pathway from poverty to by focusing "upstream" on conditions that produce nutritional status to cognitive development to school stress and either facilitate or constrain coping re- achievement. But the interrelationships among poverty, sponses. -

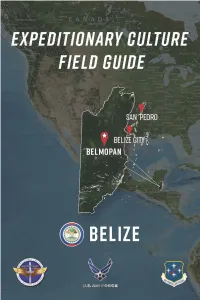

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments.