JORDAN Case Study FINAL.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land : the Case of Azraq Basin

Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The case of Azraq Basin, Jordan of Azraq in Arid Land: The case Agriculture Groundwater-Based Majd Al Naber Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Propositions: 1. Indirect regulatory measures are more efficient than direct measures in controlling the use of groundwater resources. (this thesis) 2. Decreasing the accessibility to production factors constrains, but does not fully control, groundwater-based agriculture expansion. (this thesis) 3. Remote sensing technology should be used in daily practice to monitor environmental changes. 4. Irreversible changes are more common than reversible ones in cases of over exploitation of natural resources. 5. A doctorate title is not the achievement of one's life, but a stepping-stone to one's future. 6. Positivity is required to deal with the long Ph.D. journey. Propositions belonging to the thesis, entitled Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The Case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Wageningen, 10 April 2018 Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The Case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Thesis committee Promotors Prof. Dr J. Wallinga Professor of Soil and Landscape Wageningen University & Research Co-promotor Dr F. Molle Senior Researcher, G-Eau Research Unit Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Montpellier, France Dr Ir J. J. Stoorvogel Associate Professor, Soil Geography and Landscape Wageningen University & Research Other members Prof. Dr Ir P.J.G.J. Hellegers, Wageningen University & Research Prof. Dr Olivier Petit, Université d'Artois, France Prof. Dr Ir P. van der Zaag, IHE Delft University Dr Ir J. -

Chapter IV: the Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid

Chapter IV The Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid and Mafraq – A Socio-Economic Perspective With the beginning of the first quarter of 2011, Syrian refugees poured into Jordan, fleeing the instability of their country in the wake of the Arab Spring. Throughout the two years that followed, their numbers doubled and had a clear impact on the bor- dering governorates, namely Mafraq and Irbid, which share a border with Syria ex- tending some 375 kilometers and which host the largest portion of refugees. Official statistics estimated that at the end of 2013 there were around 600,000 refugees, of whom 170,881 and 124,624 were hosted by the local communities of Mafraq and Ir- bid, respectively. This means that the two governorates are hosting around half of the UNHCR-registered refugees in Jordan. The accompanying official financial burden on Jordan, as estimated by some inter- national studies, stood at around US$2.1 billion in 2013 and is expected to hit US$3.2 billion in 2014. This chapter discusses the socio-economic impact of Syrian refugees on the host communities in both governorates. Relevant data has been derived from those studies conducted for the same purpose, in addition to field visits conducted by the research team and interviews conducted with those in charge, local community members and some refugees in these two governorates. 1. Overview of Mafraq and Irbid Governorates It is relevant to give a brief account of the administrative structure, demographics and financial conditions of the two governorates. Mafraq Governorate Mafraq governorate is situated in the north-eastern part of the Kingdom and it borders Iraq (east and north), Syria (north) and Saudi Arabia (south and east). -

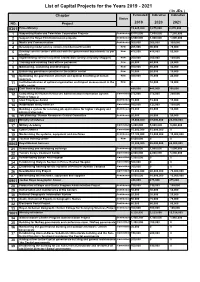

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2019 2020 2021 0301 Prime Ministry 13,625,000 9,875,000 8,870,000 1 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 8,515,000 7,650,000 7,250,000 2 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 3 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 4 Developing model service centers (middle/nourth/south) New 205,000 90,000 70,000 5 Develop service centers affiliated with the government departments as per New 475,000 415,000 50,000 priorities 6 Implementing service recipients satisfaction surveys (mystery shopper) New 200,000 200,000 100,000 7 Training and enabling front offices personnel New 20,000 40,000 20,000 8 Maintaining, sustaining and developing New 100,000 80,000 40,000 9 Enhancing governance practice in the publuc sector New 10,000 20,000 10,000 10 Optimizing the government structure and optimal benefiting of human New 300,000 70,000 20,000 resources 11 Institutionalization of optimal organization and impact measurement in the New 0 10,000 10,000 public sector 0601 Civil Service Bureau 485,000 445,000 395,000 12 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Committed 275,000 275,000 250,000 Project/ Stage 2 13 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 14 Automation and E-services Committed 160,000 125,000 100,000 15 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 15,000 10,000 10,000 administrative jobs. -

To Learn More About Our Activities in Jordan, Download This PDF

W OVERVIE JORDAN FACTS AND FIGURES 2020 JANUARY – DECEMBER 2020 SUMMARY The year 2020 has been one of uncommon challenges. In Jordan, despite measures imposed to curtail the spread of COVID-19, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) continued its work and maintained its humanitarian activities in several Governorates in the country. ICRC teams were able to support measures aimed at preventing the spread of COVID-19 especially in places of detention. Furthermore, the ICRC provided support to some families of missing persons; supported vulnerable Syrian refugees as well as host communities through livelihood projects and rehabilitated water infrastructure, while it equally trained engineers and operators to run them to ensure that host communities and Syrian refugees gain access to clean water. Some of these activities were carried out in partnership with the Jordan Red Crescent Society (JRCS), to whom we provided technical and material support to enable the JRCS deliver its humanitarian services more effectively, including in its COVID-19 response. One key aspect of our activities was the provision of equipment and facilities to the JRCS hospital. To strengthen the capacity of the health system in the management of COVID-19 infections, the ICRC provided Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and some medical supplies, while it offered training to some medical professionals on how best to respond to emergencies and enhance capacity in physical rehabilitation and provision of healthcare in detention. Consistent with its obligations to promote knowledge of International Humanitarian Law (IHL), the ICRC provided training for members of the Armed and Security Forces in Jordan and participating officers of the Police, Gendarmerie and Civil Defence (PSD), in addition to convening roundtable discussions towards raising awareness on a variety of humanitarian issues with civil society and the media. -

MA6-45 6.4.1 Quality of Brackish Water

6.4 Proposed Desalination Facilities----------------------------------------------MA6-45 6.4.1 Quality of Brackish Water and Seawater--------------------------------MA6-46 6.4.2 Quality of the Treated Water----------------------------------------------MA6-46 6.4.3 Applicable Treatment Process--------------------------------------------MA6-47 6.4.4 Development Plans---------------------------------------------------------MA6-48 6.4.4.1 Aqaba Seawater Desalination Development Plan------------------ MA6-48 6.4.4.2 Alternative Plan of Brackish Groundwater Development Plan---MA6-49 6.4.4.3 Selection of the Brackish Water Development---------------------- MA6-52 6.4.5 Preliminary Design of Aqaba Seawater Desalination Project-------- MA6-52 6.4.6 Preliminary Design of the Brackish Groundwater------------------------ MA6-57 Development Project 6.4.7 Proposed Implementation Schedule--------------------------------------MA6-62 6.5 UFW Improvement Measures-------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.1 Definition of UFW----------------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.2 Current Situation of UFW-------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.2.1 Current Situation--------------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.2.2 Problems to be Solved--------------------------------------------------MA6-67 6.5.3 Improvement Measures for UFW----------------------------------------MA6-67 6.5.3.1 Considerations for UFW Improvement Plan------------------------ MA6-67 6.5.3.2 UFW Improvement Plan-----------------------------------------------MA6-69 -

Jordan Facts and Figures 2017

JORDAN FACTS AND FIGURES January - December 2017 OVERVIEW In 2017, the International Committee of the and organizational capacities. Meanwhile, the Red Cross (ICRC) in Jordan continued to ICRC in Jordan continued to visit detainees, adapt its humanitarian response to both the restore family links and promote respect for emergency and the chronic nature of the Syrian international humanitarian law (IHL), while refugee crisis. In the reporting period, the ICRC delivering large-scale logistical support to the carried out a wide range of activities aimed other ICRC delegations in the region. at supporting both refugee and communities hosting them, primarily with the Jordan Red 40,000 people received a combination Crescent Society (JRCS). of food and essential household items or a In northern Jordan, the ICRC improved cash grant people’s access to clean water by rehabilitating water-supply networks and facilities (i.e. 212,000 people benefited from the ICRC pumping stations), while in southern Jordan, water projects in the north it helped vulnerable people cope with their 13,377 phone calls were provided to circumstances by providing food and hygiene Syrian refugees in Zaatari and Azraq camps in items. The ICRC also launched small income- order to maintain contact with their families generating projects to help refugee female- headed households strengthen their self- 25,000 metric tons of goods and medical sufficiency in a more sustainable manner. supplies were transported from Jordan to nine countries in the region To support the health care system in Jordan, the ICRC strengthened the capacity of selected 1,280 medical consultations were medical facilities in responding to medical provided to refugees in Ruwayshid transit site emergencies by providing materials, equipment and training. -

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities Key Informant Interviews / District Profiling January 2014 This project has been implemented with the support of: Syrian Refugees in Host Communities: Key Informant Interviews and District Profiling January 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As the Syrian crisis extends into its third year, the number of Syrian refugees in Jordan continues to increase with the vast majority living in host communities outside of planned camps.1 This assessment was undertaken to gain an in-depth understanding of issues related to sector specific and municipal services. In total, 1,445 in-depth interviews were conducted in September and October 2013 with key informants who were identified as knowledgeable about the 446 surveyed communities. The information collected is disaggregated by key characteristics including access to essential services by Syrian refugees, and underlying factors such as the type and location of their shelters. This project was carried out to inform more effective humanitarian planning and interventions which target the needs of Syrian refugees in Jordanian host communities. The study provides a multi-sector profile for the 19 districts of northern Jordan where the majority of Syrian refugees reside2, focusing on access to municipal and other essential services by Syrian refugees, including primary access to basic services; barriers to accessing social services; trends over time; and the prioritised needs of refugees by sector. The project is funded by the British Embassy of Amman with the support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The greatest challenge faced by Syrian refugees is access to cash, specifically cash for rent, followed by access to food assistance and non-food items for the winter season. -

Nations Unies

United Nations A/CONF.226/6 General Assembly Distr.: General 13 December 2016 Original: English United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) Quito, 17–20 October 2016 Item 8 of the provisional agenda* General debate United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) regional report for the Arab region: towards inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable Arab cities Note by the secretariat The present report was prepared by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) and the Regional Office for the Arab States of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), in collaboration with the Habitat III secretariat. A significant number of experts from different countries of the region representing various constituencies, including academia, civil society, United Nations agencies and programmes and governmental institutions, contributed to the preparation of the report. *A/CONF.226/1. K1609788 070917 A/CONF/226.6 Contents Executive summary ..................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 II. Urbanization and development .................................................................................................... 7 III. Urbanization and demography ................................................................................................... -

Evaluation of the Country Office Livelihoods Outcome – UNDP Jordan Final Report

Evaluation of the Country Office Livelihoods Outcome – UNDP Jordan Final Report 17 September 2020 Submitted to: UNDP Jordan CO Submitted by: Nahla Hassan with support from Anouchka Baldin and Marwa Ershaidat 1 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... 3 II. Programme Background ................................................................................................. 3 III. Programme Description ............................................................................................... 9 IV. Evaluation Purpose and Methodology ...................................................................... 11 4.1 Objectives of the Evaluation ......................................................................................... 11 4.2 Study design: ................................................................................................................. 12 4.3 Sampling and characteristics of Evaluation participants .................................. 12 4.4 Data Collection and Analysis ....................................................................................... 13 4.6 Ethical Standards .......................................................................................................... 13 4.7 Limitations ..................................................................................................................... 13 V. Evaluation Findings ......................................................................................................... -

Report on Value Chain Analysis: the Tomato Sector in Mafraq Governorate Jordan

International Labour Organisation Report on value chain analysis: The tomato sector in Mafraq Governorate Jordan March 2014 1 Table of Contents 1. Executive summary .................................................................................................................. 3 2. Background .............................................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Project background ............................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Mafraq Governorate ............................................................................................................. 5 2.3 The tomato sector ................................................................................................................. 6 3. Analytical framework: ILOs approach to value chain analysis ................................................ 9 3.1 The value chain ...................................................................................................................... 9 3.2 Participatory value chain development for decent work ................................................... 11 3.3 The five value chain drivers ................................................................................................. 12 4. Main findings from the analysis ............................................................................................ 13 4.1 First level: Input and sourcing ............................................................................................ -

Religion, Media, and the Digital Turn a Report for the Religion and the Public Sphere Program Social Science Research Council

Religion, Media, and the Digital Turn A Report for the Religion and the Public Sphere Program Social Science Research Council Christopher D. Cantwell and Hussein Rashid December 2015 This work carries a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. This license permits you to copy, distribute, and display this work as long as you mention and link back to the Social Science Research Council, attribute the work appropriately (including both author and title), and do not adapt the content or use it commercially. Acknowledgements We wish to start by thanking Jonathan VanAntwerpen for the invitation and Nathan Schneider for the inspiration. We would also like to thank everyone involved in the Social Science Research Council’s program on Religion and the Public Sphere for shepherding this project to completion. Candace E. West and Wei Zhu deserve particular mention, however, for their sustained engagement. In addition to the SSRC’s staff and ambassadors, we would like to thank those colleagues and interlocutors who contributed to this report in various ways. Beyond those we interviewed who are listed in the Appendix, we would like to thank Emily Floyd, Shamika Goddard, Gregory Price Grieve, Kali Handelman, Nausheen Husain, Alissa Jones Nelson, S. Brent Plate, Sally Promey, Kathryn Reklis, Nathan Schneider, and Brook Wilensky-Lanford. As we argue in this report, the study of religion has long been a collaborative endeavor. The digital age has only amplified this reality. We are grateful to everyone above for collaborating with us. 1 Preface The last decade has witnessed nothing short of a transformation in the study of religion. -

Al Za'atari Camp Population Profiling

``` AL ZA’ATARI CAMP POPULATION PROFILING Al Mafraq Governorate, Jordan Camp Population Profile April 2014 Al Za’atari Refugee Camp Population Profiling - Al Mafraq Governorate, Jordan - April 2014 SUMMARY Al Za'atari refugee camp opened in July 2012 and has since received a large influx of refugees fleeing civil war in Syria. From its outset, the population of Al Za'atari has fluctuated, with new refugees arriving while others choose to leave the camp, either through the official 'bail out' system whereby they enter host communities, or through other means. This assessment was at first primarily intended to fill the information gap regarding intentions of refugees currently residing in Al Za'atari – whether they intended to stay within the camp, move within it or leave within the coming six months – to help non-governmental organizations (NGOs) plan for the months ahead with a better estimation of beneficiary numbers. Through discussion with the Strategic Working Group for Al Za'atari the scope of the assessment was expanded to address additional information needs, such as satisfaction with services, their relationship to family members not in the camp, and current and previous livelihood strategies. Assessment results indicate that the vast majority (97.7%) of households intend to stay in Al Za’atari camp for at least six months. Agencies can thus plan according to the assumption that refugees who currently reside in Al Za'atari will remain in the camp, despite the option to move into host community that is available under the ‘bail out’ system. Certain household characteristics were found to be associated with an intention to leave the camp, including having a member with university education or a member with a disability.