User Concerns About Reinsurance Arbitration – and Attendant Lessons for Selection of Dispute Resolution Forums and Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ame R I Ca N Pr

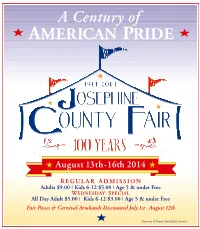

A Century of ME R I CA N R IDE A P August 1 3th- 16th 2014 R EGULAR A DMISSION Adults $9.00 | Kids 6-12 $5.00 | Age 5 & under Free W EDNESDAY S PECIAL All Day Adult $5.00 |Kids 6-12 $3.00 | Age 5 & under Free Fair Passes & Carnival Armbands Discounted July 1st - August 1 2th Courtesy of Grants Pass Daily Courier 2 2014 Schedule of Events SUBJECT TO CHANGE 9 AM 4-H/FFA Poultry Showmanship/Conformation Show (RP) 5:30 PM Open Div. F PeeWee Swine Contest (SB) 9 AM Open Div. E Rabbit Show (PR) 5:45 PM Barrow Show Awards (SB) ADMISSION & PARKING INFORMATION: (may move to Thursday, check with superintendent) 5:30 PM FFA Beef Showmanship (JLB) CARNIVAL ARMBANDS: 9 AM -5 PM 4-H Mini-Meal/Food Prep Contest (EB) 6 PM 4-H Beef Showmanship (JLB) Special prices July 1-August 12: 10 AM Open Barrow Show (SB) 6:30-8:30 PM $20 One-day pass (reg. price $28) 1:30 PM 4-H Breeding Sheep Show (JLB) Midway Stage-Mercy $55 Four-day pass (reg. price $80) 4:30 PM FFA Swine Showmanship Show (GSR) Grandstand- Truck & Tractor Pulls, Monster Trucks 5 PM FFA Breeding Sheep and Market Sheep Show (JLB) 7 PM Butterscotch Block closes FAIR SEASON PASSES: 5 PM 4-H Swine Showmanship Show (GSR) 8:30-10 PM PM Special prices July 1-August 12: 6:30 4-H Cavy Showmanship Show (L) Midway Stage-All Night Cowboys PM PM $30 adult (reg. -

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

MACARONI I JOWRNAL I I I I

· , . - - . I J . ____ ~~..........::...__ ~_~ _~~_~ ! TIrlE t I! MACARONI I JOWRNAL I I I i I, I Volume ~II I J NurnlJe~ § September, 1950 I'I , l' j • , '- 1 . • " , .- • Dakota. who w:as'named Durum Queen MCICOIronl.F,e.U;'al at Devils Lalee. N- D,. August 3. 1950, is shown stand- • ~n her husband's farm of 1,600 acres, 600 acres , .. , . VOLUME XXXII NUMBER .5 :~ i" , " .... THE MACARONI JOURNAL J 0' YOUR ' , 0 .. '" ,', TEN DAYS o.,; Begloolog Thur.day, October, • , , .nd through SalUr. day, Octob.r 14, •• Ibe Groce.. o( Am.rica ..lIJ 1.11 Hou ....iv •• o( America aboul your produClS. You'll g.1 merchandisIng help from produccn of wiDe IDd chee.e, north, east, south or west lince Nadonal Macaroni W ••k coindd •• wilh Nadooal Win. We.k and October i. Ch •••• F.ldval Monlh. Amb.r MlIJ will h.lp you KEEP Ih. cullom.rs you win • • •• ROSSOTn Specialized d~riog Nadonal Macaroni W ••k : With Amb.r'. No, 1 Semolinl your productl will have the color, texture and aavorrh .. can mak.Ii(~long CUSlomers (or YOUR brand •. Packaging Consultants are A. al.. ay., Amb.r Mill promise. prompl .hipm.ol o( (r•• h mlIJ.d lOp quality No. 1 Semolina. RighI now. , • avaUable order your No.1 Semolina req.dremeots (or the National Macaroni W ••k Sal •• Driv. (rom' Amber Mill. Ronolli is proud of the ro:c it has pln)'cd in the growth of the maca roni industry thraus •• the introduction of new techniques in mtrchal1- diJing thrDugh packtJging. -

NATIONAL Tictoricti SHOW ISSUE TOWNSHEND MORGAN-HOLSTEIN FARM BOLTON, MASS

35 SEPTEMBER, 1959 (it- MORGAN HORSE NATIONAL Tictoricti SHOW ISSUE TOWNSHEND MORGAN-HOLSTEIN FARM BOLTON, MASS. Our consignment to this year's Green Meads Morgan Weanling Sale — TOWNSHEND VIGILANTE Sire: Orcland Vigildon Dam: Windcrest Debutante Talk about New England's Red Flannel Hash this is New England's Blue Ribbon Hash. This colt is a mixture of all the best champion New England Blood. His grandsires are the famous Cornwallis, Upwey Ben Don, and Ulendon. His granddam is none other than Vigilda Burkland. His own sire ORCLAND VIGILDON was New England Champion, East- ern States Champion, Pennsylvania National Champion and Reserve Champion Harness and Saddle Horse at National Morgan Shows. He is a full brother to Orcland Leader and Vigilda Jane. His own dam, WINDCREST DEBUTANTE, winner of several champion- ships for us in 1957, is a full sister to Brown Pepper and Donnie Mac. Here is a champion for you if you bid last on this good colt! ORCLAND FARMS "Where Champions Are Born" — ULENDON BLOOD TELLS — We wish to congratulate all his offspring that placed at the 1959 National Morgan Horse Show and list the winners: SONS and DAUGHTERS: VIGILDA JANE—second year in succession winner of Mare and Foal ORCLAND LEADER—Stallion Parade HAVOLYN DANCER—Geldings over 4 years and Reserve Champion Gelding ORCLAND QUEEN BESS—Walk-Trot ridden by Linda Kean GRANDCHILDREN: MADALIN—Mares and Geldings in Harness, Ladies' Mares and Geldings in Harness, Championship Harness Stake PROMENADE—Junior Saddle Stake HILLCREST LEADER—Junior Harness Stake VIGILMARCH-2 year old Stallions in Harness BOLD VENTURE—Stallion Foals GREEN MT. -

2016 Heritage Place Thoroughbred Sale

HERITAGE PLACE THOROUGHBRED SALE Session One Sunday, October 9, 2016 Starting promptly at 1:00 PM Hips 1-55 Restaurant and Club Open Daily Phone (405) 682-4551 Fax (405) 686-1267 Please bring this catalog to the sale. SUPPLY IS LIMITED “W here Champions Are Sold” PAGE 65 IMPORTANT FACTS ALL CONSIGNORS’ UPDATES MUST BE MADE THROUGH N THE SALES OFFICE NO LATER THAN ONE HOUR PRIOR TO O THE BEGINNING OF THE SALE DAY. New buyers or buyers who have not purchased within one year must establish buyer verifi cation before purchasing. Also, any buyer exceeding the amount established T must update buyer verifi cation. Inspect horses prior to purchasing. Read Sale Conditions. If the asterisk (*) appears on the television I monitor this means a special announcement has been made concerning that hip. Buyer: Leave hip number on all horses and leave horses in original stalls. C Engagements are listed as per consignor and have not been verifi ed by the Sale Company. All purchases must be paid in cash at the time of sale. E Following the conclusion of the sale all horses must be moved from the Sale Premises by Noon, Monday, October 10, 2016. PAGE 66 Consigned by Mighty Acres, Agent for Hip No. Center Hills Farm Hip No. 1 Dark Bay or Brown Gelding 1 Storm Bird Storm Cat.......................... Terlingua Save Big Money................ A.P. Indy Dark Bay or Tomisue's Delight ............ Brown Gelding Prospectors Delite April 4, 2015 Seeking the Gold Petionville ........................ Vana Turns Nakayama Jeune .............. (2006) Seattle Slew Bal Boree .......................... Hey Hazel By SAVE BIG MONEY (2003). -

National Morgan Horse Show, July 26-29

NationalMorgan Horse Show, July 26-29 ··· BJlJJilDWilllf HHJll SPECIAL OFFER All foals will be sold at the farm at reasonable prices. Make your selection now - take deli very this fall. We have some excellent foals now with more to come. * VISITORS WELCOME * * Mr. and Mrs. J. Cecil Ferguson SISSON ROAD, GREENE, RHODE ISLAND Express 7-3963 TABLEOF CONTENTS SPECIAL FEATURES Paragraph 04027 . The Dam of Champions . 7 .f ette'tsto So You Want To Raise Morgans . a Hints To Horsekeepers . 9 Clothes Don"t Make The Rider . But • • • . 10 Correspondence Course, Pennsylvania . 16 tlie idilo1ts Correspondence Course . Wyoming . 21 Free Booklets or Booklets offered at Nominal Cost . 20 Mabel Owen To Judge Pacific Northwest All-Morgan Show . 23 The Morgan 's Long Suit . 26 Morgan Wins First In Irish Parade . 37 Dear Sir: The Univers ity of Vermont Morgan Horse Farm - A Our ad in the March issue of the Pro gress Report . 39 magazine was great - thanks for the Classes and Purse Money at Sealtle World 's Fair Horse Show 38 20th Annual Nat ional Morgan Horse Show . 39 beauti ful lay-out and the eye-catchin g News of The· Gold Cup Horse Show , Inc. 39 type. We 'll be sending our hal£-page REGULAR FEATURES for the Santa Fe Show for the Jun e or Letters to the Editor . ~ July issue, and if possible will includ e Jes' Hossin' Around . 6 a photo of the grounds to be used in Mississippi Vall ey News . 11 the same way as this last one. North of the Border . 12 New England News . -

The Macaroni Journal

• THE MACARONI JOURNAL Volume 10, Number 7 November 15, 1928 I {, " J A Monlhly Publicalir."I Devoled 10 Ihe InlerOJ/! 0/ 1\Milme;apollis;·Minn. Manu/aelure,. 0/ Macaroni NO'verrlber 15, 1928 Number 7 '- Price Cutting Cure. , ~ClCCC~ " How can price cutting be stopped? . -. Only by casting out the craze for volume at any cost and the fear of not getting the volume. This means- . a-the scientific quoting of prices based on actual cost plus reasonable profit. b-sticking to quotations. c-going after only a reasonable propor tion of the total business. d-sticking as much as . possible to your own economic territory. e-getting business by sane and ethical methods and making sure of a legiti mate profit on it. O. H. Cheney, Vice President American Bxchange Irving Trust Co. • .""'",",, IS, 1928 THE MACARONI JOURNAL J , . I , . "'-THE'-. "''''' - DAYS. .THAT ARE DREAR AND COLD By Ernest V. Madison The hil" . tJrr/u'd (orn/YfI/j fms ill MM·JVrst /l O.ft'S arr proportiollotrly as I"Dicirll' ill ,absor/!j"y shock, slra;" alld (libra/jem as th is /lrill, ull Cirri. brlt/g/' over "H' Umf'qlla Niwr fl l lI/il/cllu/"r, O"'gOll. You can depend on Mid-West Boxes- ask any shipper who uses them daily Soon it will be winter. .. l.: 'Already Nature's telegraph system IS nOlilying us that Ihis biling, The great clIlllulati\'c recurd of 1\lid-\Vcst corrllg';ltcd hoxes hllilt up in thousands blustering season is Iraveling our way. Green is changing into brown. -

Classified List of Daffodil Names, 1916

noym Horticultural Society. CLASSIFIED List of DAFFODIL NAMES, 1916. Price Is. R.H.S. OFFICES, STOkAGE ntM s.w, PROCESS I NG-ONE Lpl-D17A U.B.C. LIBRARY THE LIBRARY THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA U ' CAT. NO. AE>4.^i>- Nz H$ I Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2010 with funding from University of Britisli Columbia Library http://www.archive.org/details/classifiedlistofOOroya CLASSIFICATION OF DAFFODILS FOR USE AT ALL EXHIBITIONS OF The Royal Horticultural Society. [/if order of llic Coii>ii//.\ [n;,0.\ The enormous increase of late \cars in the number of named Daffodils and the crossing and inter-crossing of the (_)nce fairl\- distinct classes of iiiiigiii- lucdio- -Mu] parvi-coronati into \\hich the \arieties ha\e hitherto been di\'ided have made it imperativeK^ necessary to adopt some ne\v or modified Classifi- cation for Garden and Show purposes. In the Sjiring of igo8, the Council of the Royal Piorticultural Society appointed a Committee to consider the subject, and as a result of its labours all known Daffodils were divided into Seven Classes, and a Classified List was published in the same }ear. This method of Classihcation failed to meet A with general acceptance, and numerous modifications were suggested, conse- quently the Council reappointed the Committee, in 1909, to further consider the matter, with the result that the system of Classification now put forward by the authority' of the Royal Horti- cultural Society was arranged. In 1915 the Leedsii Class (R^) was sub-divided to bring it into line with the Incom- parabilis and Barrii Classes. -

Round Two Study Guide Is 88 Pages Long

How to Study for Round Two of the Preliminaries of the 2019 Scripps National Spelling Bee Think twice before printing this guide: The 2019 Round Two Study Guide is 88 pages long. We recommend using it as a digital resource rather than a printed resource. Instead, print the 2019 Round Two Study Words to use as your practice list. Learning these words will give you the best chance to show off your talent during Round Two. Your Round Two vocabulary question in the Preliminaries Test and your Round Two onstage spelling word will both come from the 2019 Round Two Study Words, available to download when you are logged in to spellingbee.com. Do you have questions about a word’s pronunciation, origin, part of speech, definition or use in a sentence? That information is waiting for you in this Study Guide. All you need to do is: 1. Hit Ctrl+F (PC) or Command+F (Mac). 2. Type the word you are looking for into the search box. If you would like further study practice, the Round Two Study Tool is also available to you when you are logged in to spellingbee.com. The Round Two Study Tool offers online spelling and vocabulary quizzes for all the words that are contained in this Round Two Study Guide. One quick reminder: The only study resource for Round One and Rounds Three and higher is Merriam-Webster Unabridged, copyright 2018, Merriam-Webster (http://unabridged.merriam-webster.com). Happy studying! 2019 Round Two Study Guide 1. abattoir \ \ This word’s elements came from French, which took them from Latin. -

Dschingis Khan

DSCHINGIS KHAN KONIGSSTUHL (GER) KONIGSKRONUNG MONSUN (GER) SURUMU (GER) MOSELLA (GER) OCOVANGO (GB) MONASIA (GER) (2010) A BROWN MR PROSPECTOR HORSE GONE WEST (USA) SECRETTAME (USA) CRYSTAL MAZE (GB) (2004) NUREYEV (USA) CRYSTAL MUSIC (USA) CRYSTAL SPRAY (GB) OCOVANGO (GB), won 3 races at 2 and 3 years and £215,374 including Prix Greffulhe, Saint Cloud, Gr.2, Prix Francois Mathet, Saint Cloud, L., placed 4 times including third in Juddmonte Grand Prix de Paris, Longchamp, Gr.1, Qatar Prix Niel, Longchamp, Gr.2, La Coupe, Longchamp, Gr.3. Sire. 1st Dam CRYSTAL MAZE (GB) (by Gone West (USA)), unraced. Dam of four winners including- OCOVANGO (GB) (2010 c. by Monsun (GER)), See above. Empress Cixi (GB) (2011 f. by Shamardal (USA)), unraced; dam of 1 winner-- Manchu (AUS) (2016 f. by Redoute's Choice (AUS)), won 1 race at 3 years and £25,274, placed 8 times including second in Lawnmaster Eulogy Stakes, Awapuni, Gr.3, fourth in Skycity Eight Carat Classic, Ellerslie, Gr.2. 2nd Dam CRYSTAL MUSIC (USA) (by Nureyev (USA)), Jt 2nd top rated 2yr old filly in Europe in 2000 and Jt 4th top rated 3yr old filly in England in 2001, won 3 races at 2 years and £255,192 including Meon Valley Stud Fillies' Mile, Ascot, Gr.1, placed 4 times viz second in Entenmanns Irish One Thousand Guineas, Curragh, Gr.1, Coronation Stakes, Ascot, Gr.1, fourth in Sagitta One Thousand Guineas, Newmarket, Gr.1, Matriarch Stakes, Hollywood Park, Gr.1. Dam of six winners including- FIRNAS (GB) (g. by Dubawi (IRE)), won 5 races at 3 to 8 years, 2021 and £77,655 including Hamdan Bin Mohammed Cruise Terminal Entisar, Meydan Racecourse, L., placed twice. -

Literature As Opera

LITERATURE AS OPERA ----;,---- Gary ,c1)midgall New York OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1977 Notes to Pages 3-1 I Chapter One r. Joseph Desaymard, Emmanuel Charier cl'apres ses lettres (1934), p. 119. The letter was probably written in 1886. a. Michel de Chabanon, De la musique considerie en elle-meme et dans ses rapports avec la parole, les langues, la poe'sie, et le theatre (1785), p. 6. 3. One good reason to avoid a law-giving approach to the question of what is operatic is simply that the legislative record of writers on opera is not very encouraging, even those writers who speak from practical experience. Con- sider these pronouncements: Wieland: "Plays whose action requires a lot of political arguments, or in which the characters are forced to deliver lengthy speeches in order to convince one another by the strength of their reasons or the flow of their rhetoric, should, accordingly, be altogether excluded from the lyrical stage." Tchaikovsky: "Operatic style should be broad, simple, and decorative." R. Strauss: "Once there's music in a work, I want to be the master, I don't want it to be subordinate to anything else. That's too humble. I don't say that poetry is inferior to music. But the true poetic dramas—Schiller, Goethe, Shakespeare—are self-sufficient; they don't need music." Adorno: "It has never been possible for the quality of music to be indif- ferent to the quality of the text with which it is associated; works such as Mozart's Cosi fan tutte and Weber's Euryanthe try to overcome the weak- nesses of their libretti through music but nevertheless are not to be salvaged by any literary or theatrical means." All these statements have at least two things in common. -

2017-HP-Falll-Min

HoofPrints Therapeutic Riding of Tucson Fall 2017 FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SANDI MOOMEY The strength and success of TROT comes from passionate and dedicated individuals – the TROT board, staff, volunteers, and our supporters – those who share their expertise and resources to meet the challenges. At the same time, they share the goodwill and excitement of making a difference in the lives of people. Together, we are on a path that ensures a bright future for TROT. TROT is pleased to welcome Sandy Webster to the TROT team as Program Director. Sandy is an internationally- recognized leader in the field of Equine-Assisted Activities and Therapies (EAAT). For more than 20 years, Sandy has helped many individuals achieve their goals, and has worked tirelessly to expand opportunities for people with disabilities and special needs. Read the full story, including other staff appointments in this issue. On Sunday, October 29, 4 p.m., SAVE THE DATES TROT MISSION treat yourself to a little Horsin’ Around! Relax and make new To enrich the lives SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 18 friends while you enjoy a mouth- of people with GATES OPEN AT 8AM watering BBQ, along with live TACK special needs NO EARLY SALES country music and dancing as the SALE using equine- sun sets on the Tanque Verde TROT - 8920 E. Woodland Rd. assisted Guest Ranch. Be there! Your activities and presence will benefit TROT therapies to students. improve physical, We are grateful for your support. 2018 Hearts & Horses Gala mental, social Together, we are changing lives SATURDAY, APRIL 7, 2018 and emotional one stride at a time.