Literature As Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ame R I Ca N Pr

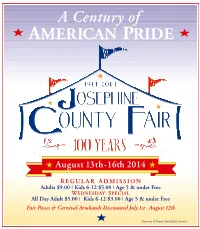

A Century of ME R I CA N R IDE A P August 1 3th- 16th 2014 R EGULAR A DMISSION Adults $9.00 | Kids 6-12 $5.00 | Age 5 & under Free W EDNESDAY S PECIAL All Day Adult $5.00 |Kids 6-12 $3.00 | Age 5 & under Free Fair Passes & Carnival Armbands Discounted July 1st - August 1 2th Courtesy of Grants Pass Daily Courier 2 2014 Schedule of Events SUBJECT TO CHANGE 9 AM 4-H/FFA Poultry Showmanship/Conformation Show (RP) 5:30 PM Open Div. F PeeWee Swine Contest (SB) 9 AM Open Div. E Rabbit Show (PR) 5:45 PM Barrow Show Awards (SB) ADMISSION & PARKING INFORMATION: (may move to Thursday, check with superintendent) 5:30 PM FFA Beef Showmanship (JLB) CARNIVAL ARMBANDS: 9 AM -5 PM 4-H Mini-Meal/Food Prep Contest (EB) 6 PM 4-H Beef Showmanship (JLB) Special prices July 1-August 12: 10 AM Open Barrow Show (SB) 6:30-8:30 PM $20 One-day pass (reg. price $28) 1:30 PM 4-H Breeding Sheep Show (JLB) Midway Stage-Mercy $55 Four-day pass (reg. price $80) 4:30 PM FFA Swine Showmanship Show (GSR) Grandstand- Truck & Tractor Pulls, Monster Trucks 5 PM FFA Breeding Sheep and Market Sheep Show (JLB) 7 PM Butterscotch Block closes FAIR SEASON PASSES: 5 PM 4-H Swine Showmanship Show (GSR) 8:30-10 PM PM Special prices July 1-August 12: 6:30 4-H Cavy Showmanship Show (L) Midway Stage-All Night Cowboys PM PM $30 adult (reg. -

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

ענליוו – Wilna – – Wilno – Vilnius

– Wilna – ווילנע – Wilno – Vilnius צו אבזערווירן און צו טראכטן… מו״לים ומתרגמים יידיים של ספרות הוגי דעות גרמניים Yiddish Publishers and TranslaTors of German auThors ThrouGh The lens of Their books ביום 23 ספטמבר 1943 חוסל גטו וילנה, כשנתיים לאחר שהוקם על ידי הגרמנים. היהודים שעוד היו בגטו גורשו או נרצחו בפונאר הסמוך. באלימות ובחוסר אנושיות הגיעה לקיצה היסטוריה בת מאות שנים של "ירושלים של הצפון" או "ירושלים דליטא", כפי שכונתה וילנה היהודית. אוצרות תרבותיים שמקורם ב"ייִדיִש לאַ נד" ובמיוחד בווילנע, שמה היידי של בירת ליטא וילנה היום, אינם משתקפים בנוף הספרותי והתאטרלי העכשווי במקום. תעשיית הוצאות הספרים של אז מציגה את העניין הרב שגילה קהל הקוראים בספרות היידית, כמו גם בתרגומים ליידיש של מחברים אירופאיים, ובמיוחד גרמנים. תרבות הקריאה תרמה, במיוחד בתוך חומות הגטו, להישרדות רוחנית. On September 23, 1943 the Vilna Ghetto, established two years earlier by occupying German forces, was liq- uidated, and the remaining Jews were either deported or murdered in the nearby Ponar Woods. With this act of brutality and inhumanity, the centuries old history of the so-called “Jerusalem of the North” or “Jerusalem of Lithuania” ended. The cultural treasures generated into a “Yidishland”, particularly in Vilna – the Yiddish name of the Lithuanian capital Vilnius – are reflected not only in the theatrical and literary worlds. The publishing indus- try of the time attested to a lively interest among reader- ship in Yiddish literature, but also on Yiddish translations of European, especially German authors. Reading helped facilitate intellectual survival, especially in the Ghetto. דער ווילנער ֿפאַ רלאַ ג ֿפון בּ. קלעצקין. בּ אָ ר י ס אָ ר ק אַ ד י י ו ו י ץ ק ל ע צ ק י ן )1875-1937( נולד הוצאות לאור, בתי דפוס בהרודיץ׳, וייסד בית הוצאה לאור משלו׃ דער Publishing Houses, Printers ווילנער ֿפאַ רלאַ ג ֿפון בּ. -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

VIVA VERDI a Small Tribute to a Great Man, Composer, Italian

VIVA VERDI A small tribute to a great man, composer, Italian. Giuseppe Verdi • What do you know about Giuseppe Verdi? What does modern Western society offer everyday about him and his works? Plenty more than you would think. • Commercials with his most famous arias, such as “La donna e` nobile”, from Rigoletto, are invading the air time of television… • Movies and cartoons have also plenty of his arias… What about stamps from all over the world carrying his image? • There are hundreds of them…. and coins and medals… …and banknotes? Well, those only in Italy, that I know of…. Statues of him are all over the world… ….and we have Verdi Squares and Verdi Streets And let’s not forget the many theaters with his name… His operas even became comic books… • Well, he was a famous composer… but it’s that the only reason? Let’s look into that… Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi Born Joseph Fortunin François Verdi on October 10, 1813 in a village near Busseto, in Emilia Romagna, at the time part of the First French Empire. He was therefore born French! Giuseppe Verdi He was refused admission by the Conservatory of Milan because he did not have enough talent… …that Conservatory now carries his name. In Busseto, Verdi met Antonio Barezzi, a local merchant and music lover, who became his patron, financed some of his studies and helped him throughout the dark years… Thanks to Barezzi, Verdi went to Milano to take private lessons. He then returned to his town, where he became the town music master. -

Verdi Falstaff

Table of Opera 101: Getting Ready for the Opera 4 A Brief History of Western Opera 6 Philadelphia’s Academy of Music 8 Broad Street: Avenue of the Arts Con9tOperae Etiquette 101 nts 10 Why I Like Opera by Taylor Baggs Relating Opera to History: The Culture Connection 11 Giuseppe Verdi: Hero of Italy 12 Verdi Timeline 13 Make Your Own Timeline 14 Game: Falstaff Crossword Puzzle 16 Bard of Stratford – William Shakespeare 18 All the World’s a Stage: The Globe Theatre Falstaff: Libretto and Production Information 20 Falstaff Synopsis 22 Meet the Artists 23 Introducing Soprano Christine Goerke 24 Falstaff LIBRETTO Behind the Scenes: Careers in the Arts 65 Game: Connect the Opera Terms 66 So You Want to Sing Like an Opera Singer! 68 The Highs and Lows of the Operatic Voice 70 Life in the Opera Chorus: Julie-Ann Whitely 71 The Subtle Art of Costume Design Lessons 72 Conflicts and Loves in Falstaff 73 Review of Philadelphia’s First Falstaff 74 2006-2007 Season Subscriptions Glossary 75 State Standards 79 State Standards Met 80 A Brief History of 4 Western Opera Theatrical performances that use music, song Music was changing, too. and dance to tell a story can be found in many Composers abandoned the ornate cultures. Opera is just one example of music drama. Baroque style of music and began Claudio Monteverdi In its 400-year history opera has been shaped by the to write less complicated music 1567-1643 times in which it was created and tells us much that expressed the character’s thoughts and feelings about those who participated in the art form as writers, more believably. -

La Favorite Opéra De Gaetano Donizetti

La Favorite opéra de Gaetano Donizetti NOUVELLE PRODUCTION 7, 9, 12, 14, 19 février 2013 19h30 17 février 2013 17h Paolo Arrivabeni direction Valérie Nègre mise en scène Andrea Blum scénographie Guillaume Poix dramaturgie Aurore Popineau costumes Alejandro Leroux lumières Sophie Tellier choréraphie Théâtre des Champs-Elysées Alice Coote, Celso Albelo, Ludovic Tézier, Service de presse Carlo Colombara, Loïc Félix, Judith Gauthier tél. 01 49 52 50 70 [email protected] Orchestre National de France Chœur de Radio France theatrechampselysees.fr Chœur du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées Coproduction Théâtre des Champs-Elysées / Radio France La Caisse des Dépôts soutient l’ensemble de la Réservations programmation du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées T. 01 49 52 50 50 theatrechampselysees.fr 5 Depuis quelques saisons, le bel canto La Favorite et tout particulièrement Donizetti ont naturellement trouvé leur place au Gaetano Donizetti Théâtre puisque pas moins de quatre des opéras du compositeur originaire Opéra en quatre actes (1840, version française) de Bergame ont été récemment Livret d’Alphonse Royer et Gustave Vaëz, d’après Les Amours malheureuses présentés : la trilogie qu’il a consacré ou Le Comte de Comminges de François-Thomas-Marie de Baculard d’Arnaud aux Reines de la cour Tudor (Maria Stuarda, Roberto Devereux et Anna Bolena) donnée en version de direction musicale Paolo Arrivabeni concert et, la saison dernière, Don Valérie Nègre mise en scène Pasquale dans une mise en scène de Andrea Blum scénographie Denis Podalydès. Guillaume Poix dramaturgie Aurore Popineau costumes Compositeur prolifique, héritier de Rossini et précurseur de Verdi, Alejandro Le Roux lumières Donizetti appartient à cette lignée de chorégraphie Sophie Tellier musiciens italiens qui triomphèrent dans leur pays avant de conquérir Paris. -

Senior Lecture Recital: Lauren Camp

Kennesaw State University College of the Arts School of Music presents Senior Lecture Recital Lauren Camp Monday, December 8, 2014 7:00 p.m. Music Building Recital Hall Fifty-fourth Concert of the 2014-15 Concert Season program Introduction Thank you The Importance of Vocal Health FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) An Die Musik Frϋlingsglaube poet Johann Uhland VINCENZO BELLINI (1801-1835) La farfalletta Il fervid desiderio MOSES HOGAN (1957-2003) Somebody’s Knockin’ at Yo’ Door Give Me Jesus Conclusion Questionnaire Thank you This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree Bachelor of Music in Music Education. Ms. Camp is a student of Alison Mann. program notes Vincenzo Bellini Bellini was a gifted opera composer of the Romantic period. He began composing at the tender age of six and was only thirty-four when he died. During the twenty-eight years of active composition, he was renowned for his vocal works and influenced other composers such as Wagner, Liszt, and Chopin. Along with the compositions of Donizetti and Rossini, Bellini’s vocal music established the bel canto (beautiful singing) style of his era. Simple arpeggiated or block-chord accompaniment figures were typical of bel canto music. The accompaniments were simple and unobtrusive, because the goal was to underscore the vocal prowess of the singer. Bell- ini’s melodies often feature long dynamic phrases, soaring climatic high notes, grace notes, and melismas, which demand great vocal agility and control. Even in this simple, bubbly song La farfalletta (The Little Butterfly), which Bellini composed at the age of twelve for a girlfriend, his bel canto vocal aesthetic is evident. -

Lucia Di Lammermoor

LUCIA DI LAMMERMOOR An in-depth guide by Stu Lewis INTRODUCTION In Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1857), Western literature’s prototypical “Desperate Housewives” narrative, Charles and Emma Bovary travel to Rouen to attend the opera, and they attend a performance of Lucia di Lammermoor. Perhaps Flaubert chose this opera because it would appeal to Emma’s romantic nature, suggesting parallels between her life and that of the heroine: both women forced into unhappy marriages. But the reason could have been simpler—that given the popularity of this opera, someone who dropped in at the opera house on a given night would be likely to see Lucia. If there is one work that could be said to represent opera with a capital O, it is Lucia di Lammermoor. Lucia is a story of forbidden love, deceit, treachery, violence, family hatred, and suicide, culminating in the mother of all mad scenes. It features a heroic yet tragic tenor, villainous baritones and basses, a soprano with plenty of opportunity to show off her brilliant high notes and trills and every other trick she learned in the conservatory, and, to top it off, a mysterious ghost haunting the Scottish Highlands. This is not to say that Donizetti employed clichés, but rather that what was fresh and original in Donizetti's hands became clichés in the works of lesser composers. As Emma Bovary watched the opera, “She filled her heart with the melodious laments as they slowly floated up to her accompanied by the strains of the double basses, like the cries of a castaway in the tumult of a storm. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Gardiner's Schumann

Sunday 11 March 2018 7–9pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT GARDINER’S SCHUMANN Schumann Overture: Genoveva Berlioz Les nuits d’été Interval Schumann Symphony No 2 SCHUMANN Sir John Eliot Gardiner conductor Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Recommended by Classic FM Streamed live on YouTube and medici.tv Welcome LSO News On Our Blog This evening we hear Schumann’s works THANK YOU TO THE LSO GUARDIANS WATCH: alongside a set of orchestral songs by another WHY IS THE ORCHESTRA STANDING? quintessentially Romantic composer – Berlioz. Tonight we welcome the LSO Guardians, and It is a great pleasure to welcome soloist extend our sincere thanks to them for their This evening’s performance of Schumann’s Ann Hallenberg, who makes her debut with commitment to the Orchestra. LSO Guardians Second Symphony will be performed with the Orchestra this evening in Les nuits d’été. are those who have pledged to remember the members of the Orchestra standing up. LSO in their Will. In making this meaningful Watch as Sir John Eliot Gardiner explains I would like to take this opportunity to commitment, they are helping to secure why this is the case. thank our media partners, medici.tv, who the future of the Orchestra, ensuring that are broadcasting tonight’s concert live, our world-class artistic programme and youtube.com/lso and to Classic FM, who have recommended pioneering education and community A warm welcome to this evening’s LSO tonight’s concert to their listeners. The projects will thrive for years to come. concert at the Barbican, as we are joined by performance will also be streamed live on WELCOME TO TONIGHT’S GROUPS one of the Orchestra’s regular collaborators, the LSO’s YouTube channel, where it will lso.co.uk/legacies Sir John Eliot Gardiner. -

Unit 7 Romantic Era Notes.Pdf

The Romantic Era 1820-1900 1 Historical Themes Science Nationalism Art 2 Science Increased role of science in defining how people saw life Charles Darwin-The Origin of the Species Freud 3 Nationalism Rise of European nationalism Napoleonic ideas created patriotic fervor Many revolutions and attempts at revolutions. Many areas of Europe (especially Italy and Central Europe) struggled to free themselves from foreign control 4 Art Art came to be appreciated for its aesthetic worth Program-music that serves an extra-musical purpose Absolute-music for the sake and beauty of the music itself 5 Musical Context Increased interest in nature and the supernatural The natural world was considered a source of mysterious powers. Romantic composers gravitated toward supernatural texts and stories 6 Listening #1 Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique (4th mvmt) Pg 323-325 CD 5/30 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QwCuFaq2L3U 7 The Rise of Program Music Music began to be used to tell stories, or to imply meaning beyond the purely musical. Composers found ways to make their musical ideas represent people, things, and dramatic situations as well as emotional states and even philosophical ideas. 8 Art Forms Close relationship Literature among all the art Shakespeare forms Poe Bronte Composers drew Drama inspiration from other Schiller fine arts Hugo Art Goya Constable Delacroix 9 Nationalism and Exoticism Composers used music as a tool for highlighting national identity. Instrumental composers (such as Bedrich Smetana) made reference to folk music and national images Operatic composers (such as Giuseppe Verdi) set stories with strong patriotic undercurrents. Composers took an interest in the music of various ethnic groups and incorporated it into their own music.