Poor Bedfellows: How Blacks and the Communism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Cold War Contested Truth

Cold War Contested Truth: Informants, Surveillance, and the Disciplining of Black Radicalism, 1947-1957 Charisse Burden-Stelly, PhD Africana Studies and Political Science Carleton College [email protected] (510) 717-9000 Introduction During the height of the era of McCarthyism, roughly 1947-1957, Black radicalism was surveilled, disciplined, discredited, and criminalized through a multitude of anticommunist technologies. These included “parallelism,” red-baiting, infiltration, and guilt by association. McCarthyism was constituted by a range of legislation meant to fortify the U.S. security state against the Communist threat, starting with the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, and including the Alien Registration Act of 1940 (commonly known as the Smith Act); the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947 (often referred to as the Taft-Hartley Act); Executive Order 9835 of 1947 (the “Loyalty Order”) and its supersession by Executive Order 10450 in 1953; the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations; and the Internal Security Act of 1950 (also known as the McCarran Act). It was under this legal architecture that scores of activists and scholars who defied Cold War statist pedagogy were indicted, deported, incarcerated, surveilled, and forced underground. This paper uses the examples of the the Peace Information Center (PIC) the Sojourners for Truth and Justice (STJ), and the Council on African Affairs (CAA) to elucidate that career confidential informants, “stool pigeons,” and “turncoats” were instrumental to the Cold War state apparatus’s transmogrification of Black radicals committed to anti-imperialism, anticolonialism, antiracism, peace, and the eradication of economic exploitation into criminals and subversives. Black 1 radicalism can be understood as African descendants’ multivalent and persistent praxis aimed at dismantling structures of domination that sustain racialized dispossession, exploitation, and class-based domination. -

Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leandership, 1930 Robert Edgar

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Articles Faculty Publications 12-15-2016 "The oM st Patient of Animals, Next to the Ass:" Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leandership, 1930 Robert Edgar Myra Ann Howser Ouachita Baptist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/articles Part of the African History Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Edgar, Robert and Howser, Myra Ann, ""The osM t Patient of Animals, Next to the Ass:" Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leandership, 1930" (2016). Articles. 87. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/articles/87 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “The Most Patient of Animals, Next to the Ass:” Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leadership, 1930 Abstract: Former South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts’ 1930 European and North American tour included a series of interactions with diasporic African and African American activists and intelligentsia. Among Smuts’s many remarks stands a particular speech he delivered in New York City, when he called Africans “the most patient of all animals, next to the ass.” Naturally, this and other comments touched off a firestorm of controversy surrounding Smuts, his visit, and segregationist South Africa’s laws. Utilizing news coverage, correspondence, and recollections of the trip, this article uses his visit as a lens into both African American relations with Africa and white American foundation work towards the continent and, especially, South Africa. -

Mary White Ovington Papers

Mary White Ovington Collection Papers, 1854-1948 6.25 linear feet Accession # 323 OCLC# The papers of Mary White Ovington were placed in the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs by Mrs. Carrie Burton Overton, Miss Ovington's secretary, in 1969, 1971 and 1973 and were opened for research in 1973. Mary White Ovington was born in Brooklyn in 1865.In 1895, after education in private schools and at Radcliffe College, she began a career as asocial worker. From 1904 on, she devoted herself to the particular problems of Negro populations in New York and other cities. In 1909 she participated in the founding of the NAACP. She remained an officer and prominent figure in the organization until her retirement in 1947. Miss Ovington was the author of several books and numerous articles. Her history of the NAACP, The Walls Came Tumbling Down, is in both the Archives Library and the Wayne State Purdy Library collections. Miss Ovington died in New York in 1951. Important subjects covered in the collection are: Unpublished autobiographical material by Miss Ovington Living conditions of the poor in New York City in the early 1900s Negroes in the American South in the early 1900s Foundation and growth of the NAACP The Civil Rights Movement, in general, up to 1947 Ovington family history, 1800-1948 Among the important correspondents are: (an index to the location of these letters will be found on the last page of the guide) Jane Addams Herbert Lehman Arna Bontemps Claude McKay Benjamin Cardozo Elmer Rice John White Chadwick Robert H. Schauffler LorenzaCole A. -

Ictnrnln Untvpraitg College and Theological Seminary

ICtnrnln Untvpraitg College and Theological Seminary Founded in DS5J THE OLDEST INSTITT'TION FOI! THE IIKJHEI! EDUCATION OF THE NE^KO. J* THE KIUST INSTITUTION NAMED FOR AlHiAIIAM LINCOLN Catalogue l!H<>-MH7 _ „ «*»»» * I'm- •' ""*•" 7 . LINCOLN UNIVERSITY IN 1014 CATALOGUE OF IGttwiltt lltmtrrBttg (JHjrHter (£mmtg, fpnna. SIXTY-SECOND YEAR 1916-1917 I'RKSS OF FERRIS & L E A C 1-1 JANUARY 1, 1917 <Eflttfrttt0 Calendar 5 PART I. The University 7 Board of Trustees of the University 7 Standing Committees of the Trustees 8 Faculty and Instructors of the University 9 Location of the University r t Needs of Lincoln University 14 The Alumni 21 PART II. The College 24 Faculty of the College 24 Courses and Degrees 24 Admission Requirements 25 Classification 3S Descriptio'n of the Courses of Instruction 46 PART III. The Theological Seminary 55 Faculty of the Theological Seminary 55 General Information 55 Admission Requirements 55 Schedule of Studies for the Seminary Year 1016-1017.. 6[ Names and Description of Courses 62 PART IV. Degrees, Honors, Catalogue of Students 60 Theological Degrees Conferred. 10,16 (>•, Theological Honors and Prizes for the Year 10,15-1916. • 6\> Academic Degrees Conferred, 1016 70 College Honors and Prizes for the Year 1915-1916 71 Honor Men 73 Students in the Theological Seminary 75 Students in the College 78 .^•N|/» . ^•^t/- . 1 ?g^ | 1017 \±qIPE Z 1017 ^r 1^1 i® ** feff1 t r JANUARY T JULY artT " JANUARY ' s n T w T F s s n T w T F s s n T W T F S • . -

CC Spaulding & RR Wright

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2011 C.C Spaulding & R.R Wright---Companions on the Road Less Traveled?: A Reconsideration of African American International Relations in the Early Twentieth Century Brandon R. Byrd College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Byrd, Brandon R., "C.C Spaulding & R.R Wright---Companions on the Road Less Traveled?: A Reconsideration of African American International Relations in the Early Twentieth Century" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626667. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-pqyd-mg78 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. C.C. Spaulding & R.R. Wright - Companions on the Road Less Traveled? A Reconsideration of African American International Relations in the Early Twentieth Century Brandon R. Byrd Raleigh, North Carolina Bachelor of Arts, Davidson College, 2009 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary January, 2011 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Brandon Ron Approved by the Committee, October, 2010 « w ~ Frances L. -

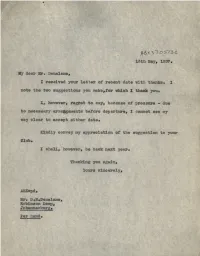

AD843-B4-012-Jpeg.Pdf

jfc&t 1,1 Ob >1c. 13th May, 1937. Hy dear Ur. Denalane, I received your letter of recent date with thanks. 1 note the two suggestions you make,for which I thank you. I, however, regret to say, because of pressure - due to necessary arrangements before departure, I cannot see my way clear to accept either date. Kindly convey my appreciation of the suggestion to your Club. I shall, however, be back next year. Thanking you again, Yours sincerely, ABXttpd. Mr. D.M.Denalane, Robinson Deep, Johannesburg. Per hand. /,• I /^Sx l i o s - f l d . 12th May, 1937. Dr, Emmet J.Scott, Howeed University, Washington, D.C# U.S.A. A • • \ ' . ' - '. My dear Ur. Scott, We have not aeon each other for over twenty years# There now Is hope of -us meeting together very soon, as I am hoping tc arrive In Amorica about the middly of June* I shall remain there until the first week bf September# I hope to have an opportunity of discussing with you our problems in Sputh Africa, and devising v/ays and means for the solution of these problems# My debt of gratitude to America and^people, both White and Black, can never be repaid# They gave me opportunities that my country did not offer to 3uch as I am# I have endeavoured to maintain the high Stsjftdards that were instilled in me by your great American Institutions# I am anxious to be a worthy representative of these Institutions and of those good people, if some of ray American friends approve of the report and the programme I wish to place before them, and are prepared to provide the means for the carrying out of the programme suggested, or whatever suggestions they may wish to make. -

Providential Design: American Negroes and Garveyism in South Africa

W&M ScholarWorks Arts & Sciences Book Chapters Arts and Sciences 9-1-2009 Providential Design: American Negroes and Garveyism in South Africa Robert Trent Vinson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/asbookchapters Part of the African History Commons, and the Other American Studies Commons Providential Design American Negroes and Garveyism in South Africa robert vinson The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA) was the largest and most widespread black movement ever. At its height in the early 1920s, the UNIA had an estimated 2 million members and sympathizers and more than 1,000 chapters in forty-three countries and territories. Founded and led by the Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey, the New York–based UNIA’s meteoric rise resulted from an agenda that included ship- ping lines, corporations, and universities; a Liberian colonization scheme; a resolute desire to reconstitute African independence; and a fierce racial pride. Outside North America and the Caribbean, these aims and idealsgeneri- cally called Garveyismhad their greatest impact in South Africa, as reflected in that country’s eight official andumerous n unofficial UNIA chapters. Garvey- ism, furthermore, pervaded black South African political, religious, educa- tional, and socioeconomic movements throughout the 1920s and 1930s.1 In this essay I make three arguments. First, Garveyism in South Africa was related to notions of “Providential Design” and modernity, which were central to the racial interface between black South Africans and “American Negroes,” a category that encompassed black West Indians as well as African Americans. Second, an international black sailing community played a crucial role in transmitting Garveyism from the Americas into South African political culture. -

Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leadership, 1930

SAFUNDI: THE JOURNAL OF SOUTH AFRICAN AND AMERICAN STUDIES, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17533171.2016.1252168 “The most patient of animals, next to the ass:” Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leadership, 1930 Robert Edgara,b and Myra Ann Houserc aDepartment of African Studies, Howard University, Washington, DC, USA; bDepartment of History, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa; cDepartment of History, Ouachita Baptist University, Arkadelphia, AR, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Former South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts’s 1930 European and South Africa; United States; North American tour included a series of interactions with diasporic Jan Smuts; Phelps-Stokes African and African American activists and intelligentsia. Among Fund; W.E.B. Du Bois; Howard Smuts’s many remarks stands a particular speech he delivered in New University York City, when he called Africans “the most patient of all animals, next to the ass.” Naturally, this and other comments touched off a firestorm of controversy surrounding Smuts, his visit, and segregationist South Africa’s laws. Utilizing news coverage, correspondence, and recollections of the trip, this article uses his visit as a lens into both African American relations with Africa and white American foundation work toward the continent and, especially, South Africa. It argues that the 1930 visit represents an early example of black internationalism and solidarity, reflecting a shift from sociocultural connections between Africa and the diaspora to creating political movements on behalf of African people. To contextualize this visit, we assess events surrounding a meeting that the Phelps-Stokes Fund organized for Smuts at Howard University, using this as a lens into the two disparate, yet interlocked, communities. -

The Seminar in Negro History

••• ANNOUNCING ••• THE SEMINAR IN NEGRO HISTORY 1938 Spring Series of Lectures under the auspices of HARLEM COMMUNITY CENTER of SOLIDARITY BR. 691 OF THE INTERNATIONAL WORKERS ORDER 317 West 125th Street Every Sunday Afternoon March, April, May .. 5-7 P.M. March Lectures LANGSTON HUGHES EUGENE GORDON MAX YERGAN JAMES W. FORD (See Description of Series on Inner Pages) March Series Ticket, 50c Per Lecture, 25c ~llJ THE SEMINAR IN NEGRO HISTORY The present social upheaval of the entire world demands a correct understanding by Negroes in America of their relationship to these events. Fascism in 193B is the world threat to the general peace and welfare of mankind. Ethiopia, Spain, China, all, fight a common enemy, Fascism. The democracies of the entire world are being challenged by the fascist war-lords. The Anti-Lynch Filibuster is an American evidence of the fascist trend. What do these world trends mean to the future of the Negro in America? The Seminar in Nego History which for the past two years has brought to the people of Harlem through eminent authorities the historical background and cultural heritage of the Negro people, feels impelled in this crucial year to discuss current historical trends and their applicaton to the problems of our people. The series of Seminars for 193B will continue every Sunday through March, April and May. We are happy to announce for March the following Seminars that will be lead by persons who have had intimate experiences in their respective fields. SUNDAY 5:00 to 7:00 P.M. SUNDAY 5:00 to 7:00 P.M. -

Archives of Transnational Modernism: Lost Networks of Art and Activism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Archives Of Transnational Modernism: Lost Networks Of Art And Activism Anne Donlon Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/419 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ARCHIVES OF TRANSNATIONAL MODERNISM: LOST NETWORKS OF ART AND ACTIVISM by ANNE DONLON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 ANNE DONLON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Jane Marcus ____________ ______________________ date Chair of Examining Committee Mario DiGangi ____________ ______________________ date Executive Officer Robert Reid-Pharr Ashley Dawson Jerry Watts Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Archives Of Transnational Modernism: Lost Networks Of Art And Activism by Anne Donlon Advisor: Jane Marcus Archives Of Transnational Modernism: Lost Networks Of Art And Activism considers the work of several intersecting figures in transnational modernism, in order to reassess the contours of race and gender in anglophone literature of the interwar period in the U.S. and Europe. Writers and organizers experimented with literary form and print culture to build and maintain networks of internationalism. -

A MORAL IMPERATIVE: the ROLE of AMERICAN BLACK CHURCHES in INTERNATIONAL ANTI-APARTHEID ACTIVISM By

A MORAL IMPERATIVE: THE ROLE OF AMERICAN BLACK CHURCHES IN INTERNATIONAL ANTI-APARTHEID ACTIVISM by Phyllis Slade Martin A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History Committee: Dr. Benedict Carton, Dissertation Director Dr. Spencer Crew, Committee Member Dr. Robert E. Edgar, Howard University Committee Member Dr. Yevette Richards Jordan, Committee Member Dr. Cynthia A. Kierner, Program Director Dr. Deborah A. Boehm-Davis, Dean College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: Spring Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA A Moral Imperative: The Role of American Black Churches in International Anti- Apartheid Activism A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Phyllis Slade Martin Master of Arts George Mason University, 2003 Director: Benedict Carton, Professor Department of History Spring Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION Dedicated in loving memory of my parents John Waymon Slade and Ruth Wilson Slade. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Bringing the stories of black American church people to the forefront was made possible by leaders who contributed to the South African liberation struggle. I thank theologian James H. Cone, the Reverends Wyatt Tee Walker, Tyrone Pitts, and Bernice Powell Jackson; the founders Sylvia Hill, George Houser, and Cecelie Counts; the activists and parishioners Adwoa Dunn-Mouton, Mary Gresham, Mark Harrison, Maghan Keita, Richard Knight, Mankekolo Mahlangu-Ngcobo, and Nkechi Taifa. Your stories shed new light on U.S. -

Race for Sanctions : the Movement Against Aparteid, 1946-1994/ Francis Njubi Nesbitt University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2002 Race for sanctions : the movement against aparteid, 1946-1994/ Francis Njubi Nesbitt University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Nesbitt, Francis Njubi, "Race for sanctions : the movement against aparteid, 1946-1994/" (2002). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 912. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/912 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UMASS. DATE DUE NOV ! 8 ?no6 UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST RACE FOR SANCTIONS: THE MOVEMENT AGAINST APARTEID, 1946-1994 A Dissertation Presented by FRANCIS NJUBI NESBITT Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2002 W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies Copyright by Francis Njubi Nesbitt 2002 All Rights Reserved RACE FOR SANCTIONS: THE MOVEMENT AGAINST APARTHEID, 1946-1994 A Dissertation Presented By FRANCIS NJUBI NESBITT Approved as to style and content: William Strickland, Member Robert Paul Wolff, Member ohn Higginsoi#0utside Member Chair Esther MA. Terry, Department 7 Afro-American Studies ABSTRACT RACE FOR SANCTIONS: THE MOVEMENT AGAINST APARTHEID, 1946-1994 FEBRUARY 2002 FRANCIS NJUBI NESBITT, B.A., UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI MA., UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME MA., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Ph.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Directed by: Professor John H.