Japheth in the Tents of Shem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memory Verse: “Bring Two of Every Living Thing Into the Ark.” Genesis 6:19

Noah’s Ark Memory Verse: “Bring two of every living thing into the ark.” Genesis 6:19 Story: 9 Here is the story of Noah. Noah was a godly man. He was without blame among the people of his time. He walked with God. 10 Noah had three sons. Their names were Shem, Ham and Japheth. 11 The earth was very sinful in God’s eyes. It was full of mean and harmful acts. 14 “So make yourself an ark out of cypress wood. Make rooms in it. Cover it with tar inside and out. 17 “I am going to bring a flood on the earth. It will destroy all life under the sky. It will destroy every living creature that breathes. Everything on earth will die. 18 “But I will make my covenant with you. You will enter the ark. Your sons and your wife and your sons’ wives will enter it with you. 19 “Bring two of every living thing into the ark. Bring male and female of them into it. They will be kept alive with you. 21 “Take every kind of food that you will need. Store it away. It will be food for you and for them.” 22 Noah did everything exactly as God commanded him. 1 Then the Lord said to Noah, “Go into the ark with your whole family. I know that you are a godly man among the people of today. 4 “Seven days from now I will send rain on the earth. It will rain for 40 days and 40 nights. -

Radical Theology and the Reorganization of the US-American Religious System

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 9 (2007) Issue 2 Article 3 Radical Theology and the Reorganization of the US-American Religious System Philippe Codde Ghent University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Codde, Philippe. "Radical Theology and the Reorganization of the US-American Religious System." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 9.2 (2007): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1219> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission the Lambeth-Jewish Forum

Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission The Lambeth-Jewish Forum Reuven Silverman, Patrick Morrow and Daniel Langton Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission The Lambeth-Jewish Forum Both Christianity and Judaism have a vocation to mission. In the Book of the Prophet Isaiah, God’s people are spoken of as a light to the nations. Yet mission is one of the most sensitive and divisive areas in Jewish-Christian relations. For Christians, mission lies at the heart of their faith because they understand themselves as participating in the mission of God to the world. As the recent Anglican Communion document, Generous Love, puts it: “The boundless life and perfect love which abide forever in the heart of the Trinity are sent out into the world in a mission of renewal and restoration in which we are called to share. As members of the Church of the Triune God, we are to abide among our neighbours of different faiths as signs of God’s presence with them, and we are sent to engage with our neighbours as agents of God’s mission to them.”1 As part of the lifeblood of Christian discipleship, mission has been understood and worked out in a wide range of ways, including teaching, healing, evangelism, political involvement and social renewal. Within this broad and rich understanding of mission, one key aspect is the relation between mission and evangelism. In particular, given the focus of the Lambeth-Jewish Forum, how does the Christian understanding of mission affects relations between Christianity and Judaism? Christian mission and Judaism has been controversial both between Christians and Jews, and among Christians themselves. -

Geographischer Index

2 Gerhard-Mercator-Universität Duisburg FB 1 – Jüdische Studien DFG-Projekt "Rabbinat" Prof. Dr. Michael Brocke Carsten Wilke Geographischer und quellenkundlicher Index zur Geschichte der Rabbinate im deutschen Sprachgebiet 1780-1918 mit Beiträgen von Andreas Brämer Duisburg, im Juni 1999 3 Als Dokumente zur äußeren Organisation des Rabbinats besitzen wir aus den meisten deutschen Staaten des 19. Jahrhunderts weder statistische Aufstellungen noch ein zusammenhängendes offizielles Aktenkorpus, wie es für Frankreich etwa in den Archiven des Zentralkonsistoriums vorliegt; die For- schungslage stellt sich als ein fragmentarisches Mosaik von Lokalgeschichten dar. Es braucht nun nicht eigens betont zu werden, daß in Ermangelung einer auch nur ungefähren Vorstellung von Anzahl, geo- graphischer Verteilung und Rechtstatus der Rabbinate das historische Wissen schwerlich über isolierte Detailkenntnisse hinausgelangen kann. Für die im Rahmen des DFG-Projekts durchgeführten Studien erwies es sich deswegen als erforderlich, zur Rabbinatsgeschichte im umfassenden deutschen Kontext einen Index zu erstellen, der möglichst vielfältige Daten zu den folgenden Rubriken erfassen soll: 1. gesetzliche, administrative und organisatorische Rahmenbedingungen der rabbinischen Amts- ausübung in den Einzelstaaten, 2. Anzahl, Sitz und territoriale Zuständigkeit der Rabbinate unter Berücksichtigung der histori- schen Veränderungen, 3. Reihenfolge der jeweiligen Titulare mit Lebens- und Amtsdaten, 4. juristische und historische Sekundärliteratur, 5. erhaltenes Aktenmaterial -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

1 Genesis 10-‐11 Study ID#12ID1337 Alright, Shall We Open Our Bibles

Genesis 10-11 Study ID#12ID1337 Alright, shall we open our Bibles tonight to Genesis 10. If you're just joining us on Wednesday, you're only nine chapters behind. So you can catch up, all of those are online, they are in video, they are on audio. We are working on translating all of our studies online into Spanish. It'll take awhile, but it's being done. We are also transcribing every study so that you can have a written copy of all that's said. You won't have to worry about notes. It'll all be there, the Scriptures will be there. So that's also in the process. It'll take awhile, but that's the goal and the direction we're heading. So you can keep that in your prayers. Tonight we want to continue in our in-depth study of this book of beginnings, the book of Genesis, and we've seen a lot if you've been with us. We looked at the beginning of the earth, and the beginning of the universe, and the beginning of mankind, and the origin of marriage, and the beginning of the family, and the beginning of sacrifice and worship, and the beginning of the gospel message, way back there in Chapter 3, verse 15, when the LORD promised One who would come that would crush the head of the serpent, preached in advance. We've gone from creation to the fall, from the curse to its conseQuences. We watched Abel and then Cain in a very ungodly line that God doesn't track very far. -

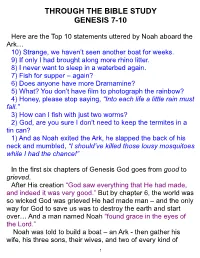

Noah Aboard the Ark… 10) Strange, We Haven’T Seen Another Boat for Weeks

THROUGH THE BIBLE STUDY GENESIS 7-10 Here are the Top 10 statements uttered by Noah aboard the Ark… 10) Strange, we haven’t seen another boat for weeks. 9) If only I had brought along more rhino litter. 8) I never want to sleep in a waterbed again. 7) Fish for supper – again? 6) Does anyone have more Dramamine? 5) What? You don’t have film to photograph the rainbow? 4) Honey, please stop saying, “Into each life a little rain must fall.” 3) How can I fish with just two worms? 2) God, are you sure I don’t need to keep the termites in a tin can? 1) And as Noah exited the Ark, he slapped the back of his neck and mumbled, “I should’ve killed those lousy mosquitoes while I had the chance!” In the first six chapters of Genesis God goes from good to grieved. After His creation “God saw everything that He had made, and indeed it was very good.” But by chapter 6, the world was so wicked God was grieved He had made man – and the only way for God to save us was to destroy the earth and start over… And a man named Noah “found grace in the eyes of the Lord.” Noah was told to build a boat – an Ark - then gather his wife, his three sons, their wives, and two of every kind of [1 animal on the earth. Noah was obedient… Which is where we pick it up tonight, chapter 7, “Then the LORD said to Noah, "Come into the ark, you and all your household, because I have seen that you are righteous before Me in this generation.” What a moving scene… When it’s time to board the Ark, God doesn’t tell Noah to go onto the ark, but to “come into the ark” – the implication is that God is onboard waiting for Noah. -

Simon Benscher (C

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE MEMBERS OF LIBERAL JUDAISM (ULPS) – KNOWN AS COUNCIL HELD ON TUESDAY 1st May 2018 AT THE LIBERAL JEWISH SYNAGOGUE SUBJECT TO SECTIONS 26 -32 OF THE MEMORANDUM AND ARTICLES OF LIBERAL JUDAISM (ULPS) PRESENT PRESIDENT / Jeromé Freedman, Louise Freedman, Rabbi Harry Jacobi VICE PRESIDENTS OFFICERS Simon Benscher (Chair), Graham Carpenter, Amanda McFeeters, (DIRECTORS) Jackie Richards, Ruth Seager, AmeLia Viney, Karen Newman, Ros CLayton RABBIS Richard Jacobi, CharLes MiddLeburgh, CharLey Baginsky, Pete Tobias COUNCIL Frank MaxweLL (Birmingham), WiLLiam GLassman (EaLing), Sam Eastmond (EaLing), Ruth SeLo (Eastbourne), Bob KamaLL (ELELS), Richard Stevens (ELELS), Josie Kinchin (FinchLey), ALison Turner (Herefordshire), Peter LobLe (LJS), ALan SoLomon (Mosaic), Jane GreenfieLd (Southgate), Stuart MacDonaLd IN Davina Bennett (Operations Manager, ELstree), Becca Fetterman, ATTENDANCE ELLie Lawson, Simon Lovick, SheLLey ShocoLinsky-Dwyer, ALexandra Simonon, Hannah Stephenson, Rafe Thurstance (minutes). OPENING PRAYER Rabbi CharLey Baginsky WELCOME AND APOLOGIES SB weLcomes everyone to the LJS, thanks the LJS for their hospitaLity. Attendees are notified that the meeting wiLL be recorded for the sake of the minutes, and asks peopLe to state any objections - none are recorded. Those in attendance are asked to state who they are before speaking. Sam Eastmond (EaLing), Davina Bennett (ELstree), ELLie Lawson (LJY-Netzer), Ruth SeLo (Eastbourne) are weLcomed to their first meeting. Apologies were received for Aaron GoLdstein, Andrew GoLdstein, Sharon GoLdstein, Nick SiLk, Peter Gordon, ALice ALphandary, Robin Moss, Lucian J. Hudson, Janet Berkman, Graham Berkman, Jennifer Lennard, Tamara Joseph, Cathy Burnstone, Ed Herman, Corinne Oppenheimer, Robin Samson, Lea MuehLstein, Joan Shopper, Nick BeLkin, and Rosie Ward. MINUTES OF THE COUNCIL MEETING OF NOVEMBER 2017 AND MATTERS ARISING The minutes were signed as an accurate record. -

Leo Baeck College at the HEART of PROGRESSIVE JUDAISM

Leo Baeck College AT THE HEART OF PROGRESSIVE JUDAISM Leo Baeck College Students – Applications Privacy policy February 2021 Leo Baeck College Registered office • The Sternberg Centre for Judaism • 80 East End Road, London, N3 2SY, UK Tel: +44 (0) 20 8349 5600 • Email: [email protected] www .lbc.ac.uk Registered in England. Registered Charity No. 209777 • Company Limited by Guarantee. UK Company Registration No. 626693 Leo Baeck College is Sponsored by: Liberal Judaism, Movement for Reform Judaism • Affiliate Member: World Union of Progressive Judaism Leo Baeck College AT THE HEART OF PROGRESSIVE JUDAISM A. What personal data is collected? We collect the following personal data during our application process: • address • phone number • e-mail address • religion • nationality We also require the following; • Two current passport photographs. • Original copies of qualifications and grade transcripts. Please send a certified translation if the documents are not in English. • Proof of English proficiency at level CERF B or International English Language Testing System Level 6 or 6+ for those whose mother tongue is not English or for those who need a Tier 4 (General) visa. • Photocopy of the passport pages containing personal information such as nationality Interviewers • All notes taken at the interview will be returned to the applications team in order to ensure this information is stored securely before being destroyed after the agreed timescale. Offer of placement • We will be required to confirm your identity. B. Do you collect any special category data? We collect the following special category data: • Religious belief C. How do you collect my data from me? We use online application forms and paper application forms. -

Archives of the West London Synagogue

1 MS 140 A2049 Archives of the West London Synagogue 1 Correspondence 1/1 Bella Josephine Barnett Memorial Prize Fund 1959-60 1/2 Blackwell Reform Jewish Congregation 1961-67 1/3 Blessings: correspondence about blessings in the synagogue 1956-60 1/4 Bradford Synagogue 1954-64 1/5 Calendar 1957-61 1/6 Cardiff Synagogue 1955-65 1/7 Choirmaster 1967-8 1/8 Choral society 1958 1/9 Confirmations 1956-60 1/10 Edgeware Reform Synagogue 1953-62 1/11 Edgeware Reform Synagogue 1959-64 1/12 Egerton bequest 1964-5 1/13 Exeter Hebrew Congregation 1958-66 1/14 Flower boxes 1958 1/15 Leo Baeck College Appeal Fund 1968-70 1/16 Leeds Sinai Synagogue 1955-68 1/17 Legal action 1956-8 1/18 Michael Leigh 1958-64 1/19 Lessons, includes reports on classes and holiday lessons 1961-70 1/20 Joint social 1963 1/21 Junior youth group—sports 1967 MS 140 2 A2049 2 Resignations 2/1 Resignations of membership 1959 2/2 Resignations of membership 1960 2/3 Resignations of membership 1961 2/4 Resignations of membership 1962 2/5 Resignations of membership 1963 2/6 Resignations of membership 1964 2/7 Resignations of membership Nov 1979- Dec1980 2/8 Resignations of membership Jan-Apr 1981 2/9 Resignations of membership Jan-May 1983 2/10 Resignations of membership Jun-Dec 1983 2/11 Synagogue laws 20 and 21 1982-3 3 Berkeley group magazines 3/1 Berkeley bulletin 1961, 1964 3/2 Berkeley bulletin 1965 3/3 Berkeley bulletin 1966-7 3/4 Berkeley bulletin 1968 3/5 Berkeley bulletin Jan-Aug 1969 3/6 Berkeley bulletin Sep-Dec 1969 3/7 Berkeley bulletin Jan-Jun 1970 3/8 Berkeley bulletin -

8460 LBC Prospectus New Brand

PROSPECTUS 2016/17 CONTENTS Rabbinic Programme ............................................................................................... 1 Structure Of The Rabbinic Programme ................................................................... 2 Graduate Diploma In Hebrew And Jewish Studies, Part 1 ...................................... 3 Graduate Diploma In Hebrew And Jewish Studies, Part 2 ...................................... 4 Postgraduate Diploma In Hebrew And Jewish Studies ........................................... 5 MA In Applied Rabbinic Theology .......................................................................... 6 Research Degrees: M.Phil, PhD ............................................................................... 7 MA In Jewish Educational Leadership ..................................................................... 8 Certificate of H.E. In Jewish Education ................................................................... 9 Foundation Course For Religion School Teachers................................................. 10 Adult Jewish Learning ........................................................................................... 11 Continual Professional Development .................................................................... 12 Interfaith Programme ............................................................................................ 12 Library And Resources ........................................................................................... 13 Application Process .............................................................................................. -

Karl Mannheim's Jewish Question

Religions 2012, 3, 228–250; doi:10.3390/rel3020228 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article Karl Mannheim’s Jewish Question David Kettler 1,* and Volker Meja 2 1 Bard College, Annandale, New York 12504, USA 2 Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John‘s NL, Canada A1C 5S7; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +845-876-5293. Received: 5 January 2012; in revised form: 26 March 2012 / Accepted: 6 April 2012 / Published: 11 April 2012 Abstract: In this paper, we explore Karl Mannheim‘s puzzling failure (or refusal) to address himself in any way to questions arising out of the position of Jews in Germany, either before or after the advent of Nazi rule—and this, notwithstanding the fact, first, that his own ethnic identification as a Jew was never in question and that he shared vivid experiences of anti-Semitism, and consequent exile from both Hungary and Germany, and, second, that his entire sociological method rested upon using one‘s own most problematic social location—as woman, say, or youth, or intellectual—as the starting point for a reflexive investigation. It was precisely Mannheim‘s convictions about the integral bond between thought grounded in reflexivity and a mission to engage in a transformative work of Bildung that made it effectively impossible for him to formulate his inquiries in terms of his way of being Jewish. It is through his explorations of the rise and fall of the intellectual as socio-cultural formation that Mannheim investigates his relations to his Jewish origins and confronts the disaster of 1933.