Noah's Wife and Heterosexual Incestuous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memory Verse: “Bring Two of Every Living Thing Into the Ark.” Genesis 6:19

Noah’s Ark Memory Verse: “Bring two of every living thing into the ark.” Genesis 6:19 Story: 9 Here is the story of Noah. Noah was a godly man. He was without blame among the people of his time. He walked with God. 10 Noah had three sons. Their names were Shem, Ham and Japheth. 11 The earth was very sinful in God’s eyes. It was full of mean and harmful acts. 14 “So make yourself an ark out of cypress wood. Make rooms in it. Cover it with tar inside and out. 17 “I am going to bring a flood on the earth. It will destroy all life under the sky. It will destroy every living creature that breathes. Everything on earth will die. 18 “But I will make my covenant with you. You will enter the ark. Your sons and your wife and your sons’ wives will enter it with you. 19 “Bring two of every living thing into the ark. Bring male and female of them into it. They will be kept alive with you. 21 “Take every kind of food that you will need. Store it away. It will be food for you and for them.” 22 Noah did everything exactly as God commanded him. 1 Then the Lord said to Noah, “Go into the ark with your whole family. I know that you are a godly man among the people of today. 4 “Seven days from now I will send rain on the earth. It will rain for 40 days and 40 nights. -

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, SBL Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019938032 Printed on acid-free paper. For our parents, grandparents, and mentors Rev. Dr. Joshua Yoo K. Ahn, PhD and Ruth Soon Hee Ahn (John Ahn) Sarah Lee and Memory of Du Soon Lee (Hannah S. An) Chun Hee Cho and Soon Ja Cho (Paul K.-K. Cho) SooHaeing Kim and Memory of DaeJak Ha (SungAe Ha) Rev. Soon-Young Hong and Hae-Sun Park (Koog-Pyoung Hong) Rev. Seok-Gu Kang and Tae-Soon Kim (Sun-Ah Kang) Rev. Dong Bin Kim and Bong Joo Lee (Hyun Chul Paul Kim) Namkyu Kim and Rev. Dr. Gilsoon Park, PhD (Sehee Kim) Rev. Yong Soon Lim and Sang Nan Yoo (Eunyung Lim) Rev. Dr. Chae-Woon Na, PhD, LittD and Young-Soon Choe (Kang-Yup Na) Kyoung Hee Nam and Soon Young Kang (Roger S. -

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION AMERICAN AND KOREAN LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN International Voices in Biblical Studies In this first of its kind collection of Korean and Korean American Landscapes of Korean biblical interpretation, essays by established and emerging scholars reflect a range of historical, textual, feminist, sociological, theological, and postcolonial readings. Contributors draw upon ancient contexts and Korean American and even recent events in South Korea to shed light on familiar passages such as King Manasseh read through the Sewol Ferry Tragedy, David and Bathsheba’s narrative as the backdrop to the prohibition against Biblical Interpretation adultery, rereading the virtuous women in Proverbs 31:10–31 through a Korean woman’s experience, visualizing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and demarcations in Galatians, and introducing the extrabiblical story of Eve and Norea, her daughter, through story (re)telling. This volume of essays introduces Korean and Korean American biblical interpretation to scholars and students interested in both traditional and contemporary contextual interpretations. Exile as Forced Migration JOHN AHN is AssociateThe Prophets Professor Speak of Hebrew on Forced Bible Migration at Howard University ThusSchool Says of Divinity.the LORD: He Essays is the on author the Former of and Latter Prophets in (2010) Honor ofand Robert coeditor R. Wilson of (2015) and (2009). Ahn Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-379-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Edited by John Ahn LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

1 Genesis 10-‐11 Study ID#12ID1337 Alright, Shall We Open Our Bibles

Genesis 10-11 Study ID#12ID1337 Alright, shall we open our Bibles tonight to Genesis 10. If you're just joining us on Wednesday, you're only nine chapters behind. So you can catch up, all of those are online, they are in video, they are on audio. We are working on translating all of our studies online into Spanish. It'll take awhile, but it's being done. We are also transcribing every study so that you can have a written copy of all that's said. You won't have to worry about notes. It'll all be there, the Scriptures will be there. So that's also in the process. It'll take awhile, but that's the goal and the direction we're heading. So you can keep that in your prayers. Tonight we want to continue in our in-depth study of this book of beginnings, the book of Genesis, and we've seen a lot if you've been with us. We looked at the beginning of the earth, and the beginning of the universe, and the beginning of mankind, and the origin of marriage, and the beginning of the family, and the beginning of sacrifice and worship, and the beginning of the gospel message, way back there in Chapter 3, verse 15, when the LORD promised One who would come that would crush the head of the serpent, preached in advance. We've gone from creation to the fall, from the curse to its conseQuences. We watched Abel and then Cain in a very ungodly line that God doesn't track very far. -

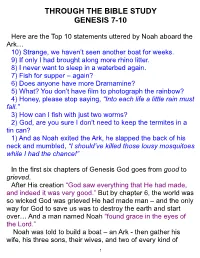

Noah Aboard the Ark… 10) Strange, We Haven’T Seen Another Boat for Weeks

THROUGH THE BIBLE STUDY GENESIS 7-10 Here are the Top 10 statements uttered by Noah aboard the Ark… 10) Strange, we haven’t seen another boat for weeks. 9) If only I had brought along more rhino litter. 8) I never want to sleep in a waterbed again. 7) Fish for supper – again? 6) Does anyone have more Dramamine? 5) What? You don’t have film to photograph the rainbow? 4) Honey, please stop saying, “Into each life a little rain must fall.” 3) How can I fish with just two worms? 2) God, are you sure I don’t need to keep the termites in a tin can? 1) And as Noah exited the Ark, he slapped the back of his neck and mumbled, “I should’ve killed those lousy mosquitoes while I had the chance!” In the first six chapters of Genesis God goes from good to grieved. After His creation “God saw everything that He had made, and indeed it was very good.” But by chapter 6, the world was so wicked God was grieved He had made man – and the only way for God to save us was to destroy the earth and start over… And a man named Noah “found grace in the eyes of the Lord.” Noah was told to build a boat – an Ark - then gather his wife, his three sons, their wives, and two of every kind of [1 animal on the earth. Noah was obedient… Which is where we pick it up tonight, chapter 7, “Then the LORD said to Noah, "Come into the ark, you and all your household, because I have seen that you are righteous before Me in this generation.” What a moving scene… When it’s time to board the Ark, God doesn’t tell Noah to go onto the ark, but to “come into the ark” – the implication is that God is onboard waiting for Noah. -

Ten Ordinary People with an Extraordinary Story A

TEN ORDINARY PEOPLE WITH AN EXTRAORDINARY STORY When you read Genesis 18, you’re actually picking up the story of how God is continually orchestrating His plan to make Israel a great nation. It’s the story of how one nation, born of an ordinary man and an ordinary woman with more than their share of problems changed the history of the world—for eternity. So if that sounds like you and you wonder how you could be of any significant value to the Kingdom of God—then listen up this morning, because this story is for you. Read Genesis 14; 18-19 Lot was Abraham’s nephew. In Genesis 14, Lot is given a chance to choose which part of the Promised Land he wants for his own. He selects an area known as Sodom – which bears the namesake for the word sodomy—which seems like a questionable decision about where to relocate your family—but like I said, the Bible isn’t afraid to take us places where ordinary people make messy decisions. This whole enterprise is based on a promise from God to Abraham, that he would have a son; and his children’s children would eventually grow into a vast nation of God-fearing people. But that takes a few hundred years, so in the meanwhile, Lot and Abraham are doing OK. Lot raises a family in the land of the Sodomites and gets himself elected as a judge. Then he finds himself in the middle of a war between two tribal groups and Uncle Abraham has to gather his 318 Navy Seals of the day to rescue Lot. -

The Wives of Solomon

THE WIVES OF SOLOMON. BY MONCURE D. CONWAY. " CCORDING to the first book of Kings, Solomon's half-brother, ft Adonijah, after the defeat of an alleged (perhaps mythical) effort to recover the throne of which he had been defrauded, sub mitted himself to Solomon. He had become enamored of the vir gin who had been brought to the aged King David to try to revive some vitality in him; and he came to Bathsheba asking her to re quest her son the king to give him this damsel as his wife. Bath sheba proffered this "small petition" for Adonijah, but Solomon was enraged, and ironically suggested that she should ask the king dom itself for Adonijah, whom he straightway ordered to execu tion. The immediate context indicates that Solomon suspected in this petition a plot against his throne. A royal father's harem was inherited by a royal son, and its possession is supposed to have in volved certain rights of succession: this is the only interpretation I have ever heard of the extreme violence of Solomon. But I have never been satisfied with this explanation. Would Adonijah have requested, or Bathsheba asked as a "small" thing, a favor touch ing the king's tenure? The story as told in the Book of Kings appears diplomatic, and several details suggest that in some earlier legend the strife between the half- brothers had a more romantic relation to "Abishag the Shunammite," who is described as "very fair." Abishag is interpreted as meaning "father of error," and though that translation is of doubtful accuracy, its persistence in dicates the place occupied by her in early tradition. -

Jewish Children's Garden Curriculum

ginat ha’yeladim Jewish Children’s Children’s Jewish CurriculumGarden Center Children’s Shalom of staff the by developed Center Community Jewish Asheville the at JCCs of North America ginat ha’yeladim Jewish Children’s Garden Curriculum developed by the staff of Shalom Children’s Center at the Asheville Jewish Community Center Made possible by a grant from The Covenant Foundation www.covenantfn.org © 2010 Asheville Jewish Community Center 236 Charlotte Street, Asheville NC 28801 (828) 253-0701 www.jcc-asheville.org Ginat Ha’Yeladim Table of Contents Why a “Jewish” Garden for Young Children? . iii Design and Implementation of Our Garden Space . .v Jewish Values in the Garden . 1 Spring Autumn Lesson 1: Early Spring Hello . 3 Lesson 23: Color Hunt . 23 Lesson 2: Soil Exploration . 4 Lesson 24: Fall Crops . 24 Lesson 3: Germination View . 4 Lesson 25: Bees and Honey, Rosh Hashanah . 24 Lesson 4: Early Spring Seed Planting . 5 Lesson 26: Autumnal Equinox . 25 Lesson 5: Seed Starting . 6 Lesson 27: Root Vegetable Harvest/ Lesson 6: Measuring Sprouts and Seedlings . 7 Digging Potatoes . 26 Lesson 7: Weed Identification . 8 Lesson 28: Sukkot, Shemini Atzerat and Praying for Rain . 27 Lesson 8: Bed Planting . 9 Lesson 29: Lunar Phases . 28 Lesson 9: Seed Comparison . 10 Lesson 30: Seed Saving . 29 Lesson 10: Mud Painting . 10 Lesson 31: Autumn Leaf Color . 30 Lesson 11: Transplanting Plants/Seedlings . 11 Lesson 32: Frost Effects . 31 Lesson 12: Havdalah Matsa Smells . 12 Lesson 33: Animals in Winter . 32 Lesson 13: Introduction to Watering . 13 Lesson 34: Winterizing/Tucking in the Garden . -

Ken Ham Biography

Ken A. Ham President/CEO Answers in Genesis Ken Ham is the president and co-founder of Answers in Genesis, an apologetics (i.e., Bible defending) ministry upholding the authority of the Bible from the first verse. The visionary behind the popular, high-tech Creation Museum near Cincinnati – which has had more than 2.5 million visitors in eight years – and also the future Ark Encounter, Ham is also a best-selling author, (“The Lie,” “Already Gone”) popular speaker, and host of a daily radio feature on 1,000 plus stations. Ham, a native of Australia, earned a bachelor’s degree in applied science (with an emphasis in environmental biology) from the Queensland Institute of Technology and a diploma of education at the University of Queensland in Brisbane. Upon graduation, Ham began his initial career as a science teacher in Australia’s public schools. He holds three honorary doctorates. In 1974, a friend from church told Ham about a book called “The Genesis Flood,” in which Drs. Henry Morris and John Whitcomb scientifically explain the geologic-transforming effects of Noah’s global Flood. Over 40 years later, it is appropriate that Ham will be opening a life-size Noah’s Ark south of Cincinnati (July 7, 2016). Burdened to tell others the facts supporting a biblical view of creation and the truth of Scripture, Ham spent his weekends speaking to various groups about creationism. In 1979, Ham left his teaching position and co-founded The Creation Science Foundation (CSF) out of his home. He borrowed money to build an extension onto his house and used a small retirement payment to buy the ministry’s first photocopier and electric typewriter. -

Only the Righteous Escape God's Wrath

Through the Bible Series: Genesis Passage for This Week: Only the Righteous Escape Genesis 6:9-8:19 God’s Wrath Key Terms: Violence: The Hebrew Introduction: word is much broader than Were you one of those kids shaking under the blankets during a just murder. It is used to thunderstorm? Running and screaming to mom and dad when include unjust treatment lightning struck? Maybe you have had to hold a child and calm him (Gen 16:5; Amos 3:10), or her back to sleep during a torrential downpour. Imagine the anxiety in Noah’s heart, wondering if his pitch was strong enough to injurious legal testimony seal cypress against the strongest historical winds. Imagine telling (Deut 19:16), deadly Shem that he would live through twenty five more nights of thunder assault (Gen 49:5), and as the boat rocked another wave. How? By finding comfort in the rape (Jer 13:22). knowledge that God was near and had promised safety. Gopher Wood: This is a The Place of the Passage: transliteration of the God’s creation was marred by sin, and as the population grew so did Hebrew word. While the evil’s reach. Murder and immorality are introduced into society, and exact specie of tree is eventually God’s judgment comes swiftly. God only allows a few to survive the flood, but His covenant after the waters subside offers unknown, many modern blessing to the world’s future generations. translations render the term as “cypress” (e.g. NEB, NIV, NRSV). I. Primeval History: Creating for Blessing (1:11-11:26) A. -

Introduction

Introduction When the Khazar ruler Joseph wrote his response to Hasdai ibn Shaprut, a dig- nitary of the Caliph of Córdoba Abd Al-Rahman (912–961), in the mid-tenth century, he could have hardly imagined the approaching end of the Khazar Khaganate, and probably to his own rule too. The king of Togarmah (the khagan-bek?),1 Joseph, described Khazaria as a flourishing state, whose rulers governed over numerous peoples and tribes, a state that was capable of stop- ping the Rus’ and the other enemies of the Arab Caliphate from devastating all of its lands.2 Joseph’s description of the Khazar Khaganate from the mid-tenth century is not accepted by most historians. At the same time, Joseph’s letter in its unabridged and abridged edition, together with the Cambridge Document, are the only authentic Khazar written sources that exist today. This requires greater caution in accepting or denying the authenticity of the information they contain. We should ask ourselves: why does the Khazar ruler’s view of his own coun- try differ so much from those of most modern scientists? Did he want to depict Khazaria as a powerful nation—and a kind of a defender of the Caliphate at that—on purpose, in order to seek help from the Muslim countries3 (although it is unclear how the Córdoba Umayyads could have helped Khazaria), or are the described territorial possessions an expression of his claims?4 And what if, ultimately, the solution to the posed questions does not lie in Joseph’s letter, but in the modern view of Khazaria and the basis on which it is established? This leads to the issue of the reasons why the Khazar Khaganate gradually lost its influence and power.