The International Journal of Meteorology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portugal – an Atlantic Extreme Weather Lab

Portugal – an Atlantic extreme weather lab Nuno Moreira ([email protected]) 6th HIGH-LEVEL INDUSTRY-SCIENCE-GOVERNMENT DIALOGUE ON ATLANTIC INTERACTIONS ALL-ATLANTIC SUMMIT ON INNOVATION FOR SUSTAINABLE MARINE DEVELOPMENT AND THE BLUE ECONOMY: FOSTERING ECONOMIC RECOVERY IN A POST-PANDEMIC WORLD 7th October 2020 Portugal in the track of extreme extra-tropical storms Spatial distribution of positions where rapid cyclogenesis reach their minimum central pressure ECMWF ERA 40 (1958-2000) Events per DJFM season: Source: Trigo, I., 2006: Climatology and interannual variability of storm-tracks in the Euro-Atlantic sector: a comparison between ERA-40 and NCEP/NCAR reanalyses. Climate Dynamics volume 26, pages127–143. Portugal in the track of extreme extra-tropical storms Spatial distribution of positions where rapid cyclogenesis reach their minimum central pressure Azores and mainland Portugal On average: 1 rapid cyclogenesis every 1 or 2 wet seasons ECMWF ERA 40 (1958-2000) Events per DJFM season: Source: Trigo, I., 2006: Climatology and interannual variability of storm-tracks in the Euro-Atlantic sector: a comparison between ERA-40 and NCEP/NCAR reanalyses. Climate Dynamics volume 26, pages127–143. … affected by sting jets of extra-tropical storms… Example of a rapid cyclogenesis with a sting jet over mainland 00:00 UTC, 23 Dec 2009 Source: Pinto, P. and Belo-Pereira, M., 2020: Damaging Convective and Non-Convective Winds in Southwestern Iberia during Windstorm Xola. Atmosphere, 11(7), 692. … affected by sting jets of extra-tropical storms… Example of a rapid cyclogenesis with a sting jet over mainland Maximum wind gusts: Official station 140 km/h Private station 00:00 UTC, 23 Dec 2009 203 km/h (in the most affected area) Source: Pinto, P. -

Modelling, Meteorology, Impacts Preparedness

ADVANCES IN HURRICANE RESEARCH MODELLING, METEOROLOGY, PREPAREDNESS AND IMPACTS Edited by Kieran Hickey ADVANCES IN HURRICANE RESEARCH - MODELLING, METEOROLOGY, PREPAREDNESS AND IMPACTS Edited by Kieran Hickey Advances in Hurricane Research - Modelling, Meteorology, Preparedness and Impacts http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/3399 Edited by Kieran Hickey Contributors Eric Hendricks, Melinda Peng, Alexander Grankov, Vladimir Krapivin, Svyatoslav Marechek, Mariya Marechek, Alexander Mil`shin, Evgenii Novichikhin, Sergey Golovachev, Nadezda Shelobanova, Anatolii Shutko, Gary Moynihan, Daniel Fonseca, Robert Gensure, Jeff Novak, Ariel Szogi, Ken Stone, Xuefeng Chu, Don Watts, Mel Johnson, Gunnar Schade, Qin Chen, Kelin Hu, Patrick FitzPatrick, Dongxiao Wang, Kieran Richard Hickey Published by InTech Janeza Trdine 9, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia Copyright © 2012 InTech All chapters are Open Access distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. After this work has been published by InTech, authors have the right to republish it, in whole or part, in any publication of which they are the author, and to make other personal use of the work. Any republication, referencing or personal use of the work must explicitly identify the original source. Notice Statements and opinions expressed in the chapters are these of the individual contributors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. No responsibility is accepted for the accuracy of information contained in the published chapters. The publisher assumes no responsibility for any damage or injury to persons or property arising out of the use of any materials, instructions, methods or ideas contained in the book. -

Program At-A-Glance

Sunday, 29 September 2019 Dinner (6:30–8:00 PM) ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ Monday, 30 September 2019 Breakfast (7:00–8:00 AM) Session 1: Extratropical Cyclone Structure and Dynamics: Part I (8:00–10:00 AM) Chair: Michael Riemer Time Author(s) Title 8:00–8:40 Spengler 100th Anniversary of the Bergen School of Meteorology Paper Raveh-Rubin 8:40–9:00 Climatology and Dynamics of the Link Between Dry Intrusions and Cold Fronts and Catto Tochimoto 9:00–9:20 Structures of Extratropical Cyclones Developing in Pacific Storm Track and Niino 9:20–9:40 Sinclair and Dacre Poleward Moisture Transport by Extratropical Cyclones in the Southern Hemisphere 9:40–10:00 Discussion Break (10:00–10:30 AM) Session 2: Jet Dynamics and Diagnostics (10:30 AM–12:10 PM) Chair: Victoria Sinclair Time Author(s) Title Breeden 10:30–10:50 Evidence for Nonlinear Processes in Fostering a North Pacific Jet Retraction and Martin Finocchio How the Jet Stream Controls the Downstream Response to Recurving 10:50–11:10 and Doyle Tropical Cyclones: Insights from Idealized Simulations 11:10–11:30 Madsen and Martin Exploring Characteristic Intraseasonal Transitions of the Wintertime Pacific Jet Stream The Role of Subsidence during the Development of North American 11:30–11:50 Winters et al. Polar/Subtropical Jet Superpositions 11:50–12:10 Discussion Lunch (12:10–1:10 PM) Session 3: Rossby Waves (1:10–3:10 PM) Chair: Annika Oertel Time Author(s) Title Recurrent Synoptic-Scale Rossby Wave Patterns and Their Effect on the Persistence of 1:10–1:30 Röthlisberger et al. -

WMO Statement on the Status of the Global Climate in 2011

WMO statement on the status of the global climate in 2011 WMO-No. 1085 WMO-No. 1085 © World Meteorological Organization, 2012 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate this publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chair, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 84 03 P.O. Box 2300 Fax: +41 (0) 22 730 80 40 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-92-63-11085-5 WMO in collaboration with Members issues since 1993 annual statements on the status of the global climate. This publication was issued in collaboration with the Hadley Centre of the UK Meteorological Office, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; the Climatic Research Unit (CRU), University of East Anglia, United Kingdom; the Climate Prediction Center (CPC), the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS), the National Hurricane Center (NHC) and the National Weather Service (NWS) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States of America; the Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) operated by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), United States; the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), United States; the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), United Kingdom; the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC), Germany; and the Dartmouth Flood Observatory, United States. -

Idealised Simulations of Stingjet Cyclones

Idealised simulations of sting-jet cyclones Article Published Version Baker, L. H., Gray, S. L. and Clark, P. A. (2014) Idealised simulations of sting-jet cyclones. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 140 (678). pp. 96-110. ISSN 1477-870X doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.2131 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/33269/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher's version if you intend to cite from the work. Published version at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/qj.2131/full To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/qj.2131 Publisher: Royal Meteorological Society All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading's research outputs online Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. (2013) Idealised simulations of sting-jet cyclones L. H. Baker,* S. L. Gray and P. A. Clark Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, UK *Correspondence to: L. H. Baker, Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, Earley Gate, PO Box 243, Reading RG6 6BB, UK. E-mail: [email protected] An idealised modelling study of sting-jet cyclones is presented. Sting jets are descend- ing mesoscale jets that occur in some extratropical cyclones and produce localised regions of strong low-level winds in the frontal fracture region. -

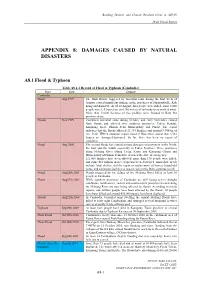

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Hurricane & Tropical Storm

5.8 HURRICANE & TROPICAL STORM SECTION 5.8 HURRICANE AND TROPICAL STORM 5.8.1 HAZARD DESCRIPTION A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (NOAA, 2013). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. The average wind speeds for tropical storms and hurricanes are listed below: . A tropical depression has a maximum sustained wind speeds of 38 miles per hour (mph) or less . A tropical storm has maximum sustained wind speeds of 39 to 73 mph . A hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 74 mph or higher. In the western North Pacific, hurricanes are called typhoons; similar storms in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific Ocean are called cyclones. A major hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 111 mph or higher (NOAA, 2013). Over a two-year period, the United States coastline is struck by an average of three hurricanes, one of which is classified as a major hurricane. Hurricanes, tropical storms, and tropical depressions may pose a threat to life and property. These storms bring heavy rain, storm surge and flooding (NOAA, 2013). The cooler waters off the coast of New Jersey can serve to diminish the energy of storms that have traveled up the eastern seaboard. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Tuesday Volume 519 23 November 2010 No. 77 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 23 November 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 147 23 NOVEMBER 2010 148 scrapped entirely. It is critical of the way they work, and House of Commons it is clear that they are not working as intended, but the Government are hoping to take a balanced view. We Tuesday 23 November 2010 must obviously protect the public against dangerous people and the risk of serious offences being committed on release. On the other hand, about 10% of the entire The House met at half-past Two o’clock prison population will be serving IPP sentences by 2015 at the present rate of progress, and we cannot keep piling up an ever-mounting number of people who are PRAYERS likely never to be released. Mr Jack Straw (Blackburn) (Lab): Does the Secretary [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] of State accept that it is inherent in both life sentences and the concept of IPP sentences, which are widely supported throughout the Chamber, that many prisoners Oral Answers to Questions will be tariff-expired because the idea is that they are not released until it is judged that it is safe to do so? Does he also accept that although it is true that the precise construction of the clauses was inappropriate JUSTICE and led to some very short tariffs, since the changes that I introduced in 2008, the number of new IPP sentenced The Secretary of State was asked— prisoners has dropped by 50% from about 1,500 to under 1,000 a year? Would it not be far better for public Imprisonment for Public Protection safety to let that work through instead of prematurely releasing such prisoners? 1. -

Tropical Storm Maria Threatens Eastern Caribbean 10 September 2011, by DANICA COTO , Associated Press

Tropical Storm Maria threatens eastern Caribbean 10 September 2011, By DANICA COTO , Associated Press Virgin Islands on Saturday morning, where the storm is expected to dump up to 6 inches (15 centimeters) of rain, said Walter Snell with the National Weather Service office in Puerto Rico. "Residents should be prepared for whatever the worst this storm can do," he said. Maria is forecast to become a Category 1 hurricane late Monday and possibly a Category 2 hurricane by Tuesday, when it is expected to pass just east of the Bahamas as it continues on a northward path, This NOAA satellite image taken Friday, September 9, the hurricane center said. 2011 at 1:45 PM EDT shows Hurricane Katia located about 385 miles south-southwest of Halifax, Nova Flight cancellations were reported across the Scotia. The system remains at Category 1 strength with Caribbean region Friday. maximum winds at 85 mph and will continue moving northeastward and further away from the East Coast of The U.S. Virgin Islands government said it would the U.S. To the south, Tropical Storm Maria is about 135 close its airport Saturday and has advised an miles northeast of Barbados with maximum sustained winds at 45 mph. Tropical storm warnings are in effect estimated 3,000 tourists currently in the territory to for most of the eastern Caribbean Islands from the stay indoors. Lesser Antilles to the Bahamas. In the Gulf of Mexico, Tropical Storm Nate is located about 150 miles west of In Puerto Rico, the government urged tourists to Campeche, Mexico with maximum winds at 50 mph. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the placing of this thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with the access for academic purposes. Brno, 30th March 2018 …………………………………………. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. for his kind help and constant guidance throughout my work. Bc. Lukáš Opavský OPAVSKÝ, Lukáš. Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis; Diploma Thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, English Language and Literature Department, 2018. XX p. Supervisor: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Annotation The purpose of this thesis is an analysis of a corpus comprising of opening sentences of articles collected from the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Four different quality categories from Wikipedia were chosen, from the total amount of eight, to ensure gathering of a representative sample, for each category there are fifty sentences, the total amount of the sentences altogether is, therefore, two hundred. The sentences will be analysed according to the Firabsian theory of functional sentence perspective in order to discriminate differences both between the quality categories and also within the categories. -

Extreme Wind

Enabling Resilient UK Energy Infrastructure: Natural Hazard Characterisation Technical Volumes and Case Studies Volume 3: Extreme Wind LC 0064_18V3 Legal Statement © Energy Technologies Institute LLP (except where and to the extent expressly stated otherwise) This document has been prepared for the Energy Technologies Institute LLP (ETI) by EDF Energy R&D UK Centre Limited, the Met Office, and Mott MacDonald Limited. This document is provided for general information only. It is not intended to amount to advice on which you should rely. You must obtain professional or specialist advice before taking, or refraining from, any action on the basis of the content of this document. This document should not be relied upon by any other party or used for any other purpose. EDF Energy R&D UK Centre Limited, the Met Office, Mott MacDonald Limited and (for the avoidance of doubt) ETI (We) make no representations and give no warranties or guarantees, whether express or implied, that the content of this document is accurate, complete, up to date, or fit for any particular purpose. We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this document being relied upon by you, any other party, or being used for any purpose, or containing any error or omission. Except for death or personal injury caused by our negligence or any other liability which may not be excluded by applicable law, We will not be liable for any loss or damage, whether in contract, tort (including negligence), breach of statutory duty, or otherwise, even if foreseeable, arising under or in connection with use of or reliance on any content of this document. -

THE RANGEFINDER the Newsletter of the Oak Ridge Sportsmen’S Association

THE RANGEFINDER The Newsletter of the Oak Ridge Sportsmen’s Association December 2011 Volume 20 Number 12 The current membership count is at approximately 2080+ members Please remember that when using any of the ORSA Ranges safety should be your #1 concern. Everyone must be diligent in observing and correcting unsafe actions by anyone on the Ranges. Also remember that you should always wear proper EYE & EAR protection regardless of whether you are shooting or just watching. ORSA WEBSITE: ORSAONLINE.ORG ORSA MEMBERSHIP INFO: JOINORSA.ORG SAVE THE DATE It's that time of year again when we remind you that the ORSA Annual Party is right around the corner. It will be held Wednesday, December 7, at 7 p.m. in our Club House. Drinks & ham will be supplied by the club just bring a covered dish to share. Call Ed Johnson 483-9573 to RSVP UPCOMING MEMBERSHIP ORIENTATION SESSIONS Membership will offer the mandatory orientation sessions for new members on about the 3rd Tuesday of each month in the ORSA Clubhouse. If you are a new applicant to ORSA and unsure of your current whether you should attend one of the upcoming sessions please contact me at [email protected]. Attending the mandatory orientation sessions prior to being approved as a new member will not grant you access to the facility any sooner. An email confirming the current status of your application is usually sent approximately 7-10 days prior to the scheduled orientation session. All sessions will be at 6:30pm at the clubhouse unless otherwise noted in your email confirmation.