The Impact of Environmental Protests in the People's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

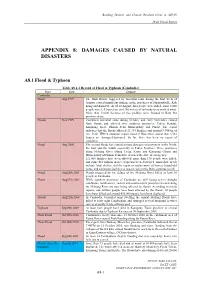

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Tropical Cyclone Temperature Profiles and Cloud Macro-/Micro-Physical Properties Based on AIRS Data

atmosphere Article Tropical Cyclone Temperature Profiles and Cloud Macro-/Micro-Physical Properties Based on AIRS Data 1,2, 1, 3 3, 1, 1 Qiong Liu y, Hailin Wang y, Xiaoqin Lu , Bingke Zhao *, Yonghang Chen *, Wenze Jiang and Haijiang Zhou 1 1 College of Environmental Science and Engineering, Donghua University, Shanghai 201620, China; [email protected] (Q.L.); [email protected] (H.W.); [email protected] (W.J.); [email protected] (H.Z.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Severe Weather, Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Beijing 100081, China 3 Shanghai Typhoon Institute, China Meteorological Administration, Shanghai 200030, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (B.Z.); [email protected] (Y.C.) The authors have the same contribution. y Received: 9 October 2020; Accepted: 29 October 2020; Published: 2 November 2020 Abstract: We used the observations from Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) onboard Aqua over the northwest Pacific Ocean from 2006–2015 to study the relationships between (i) tropical cyclone (TC) temperature structure and intensity and (ii) cloud macro-/micro-physical properties and TC intensity. TC intensity had a positive correlation with warm-core strength (correlation coefficient of 0.8556). The warm-core strength increased gradually from 1 K for tropical depression (TD) to >15 K for super typhoon (Super TY). The vertical areas affected by the warm core expanded as TC intensity increased. The positive correlation between TC intensity and warm-core height was slightly weaker. The warm-core heights for TD, tropical storm (TS), and severe tropical storm (STS) were concentrated between 300 and 500 hPa, while those for typhoon (TY), severe typhoon (STY), and Super TY varied from 200 to 350 hPa. -

China, Social Media, and Environmental Protest

CHINA, SOCIAL MEDIA, AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTEST: CIVIC ENGAGEMENT ON NETWORKS OF SCREENS AND STREETS by Elizabeth Ann Brunner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Communication The University of Utah May 2016 Copyright © Elizabeth Ann Brunner 2016 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Elizabeth Ann Brunner has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Kevin Michael DeLuca , Chair 2/23/2016 Date Approved Marouf Hasian , Member 2/23/2016 Date Approved Sean Lawson , Member 2/23/2016 Date Approved Kent Ono , Member 2/23/2016 Date Approved Janet Theiss , Member 2/23/2016 Date Approved and by Kent Ono , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Communication and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT This dissertation advances a networked approach to social movements via the study of contemporary environmental protests in China. Specifically, I examine anti- paraxylene protests that occurred in 2007 in Xiamen, in 2011 in Dalian, and in 2014 in Maoming via news reports, social media feeds, and conversations with witnesses and participants in the protests. In so doing, I contribute two important concepts for social movement scholars. The first is the treatment of protests as forces majeure that disrupt networks and force the renegotiation of relationships. This turn helps scholars to trace the movement of the social via changes in human consciousness as well as changes in relationships. The second concept I advance is wild public networks, which take seriously new media as making possible different forms of protest. -

Typhoon Effects on the South China Sea Wave Characteristics During Winter Monsoon

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2006-03 Typhoon effects on the South China Sea wave characteristics during winter monsoon Cheng, Kuo-Feng Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/2885 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS TYPHOON EFFECTS ON THE SOUTH CHINA SEA WAVE CHARACTERISTICS DURING WINTER MONSOON by CHENG, Kuo-Feng March 2006 Thesis Advisor: Peter C. Chu Second Reader: Timour Radko Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED March 2006 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE: Typhoon Effects on the South China Sea Wave 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Characteristics during Winter Monsoon 6. AUTHOR(S) Kuo-Feng Cheng 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION REPORT Monterey, CA 93943-5000 NUMBER 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Appendix 3 Selection of Candidate Cities for Demonstration Project

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report APPENDIX 3 SELECTION OF CANDIDATE CITIES FOR DEMONSTRATION PROJECT Table A3-1 Long List Cities (No.1-No.62: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-1 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-2 Long List Cities (No.63-No.124: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-2 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-3 Long List Cities (No.125-No.186: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-3 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-4 Long List Cities (No.187-No.248: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-4 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-5 Long List Cities (No.249-No.310: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-5 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-6 Long List Cities (No.311-No.372: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. -

Minnesota Weathertalk Newsletter for Friday, January 7Th, 2011

Minnesota WeatherTalk Newsletter for Friday, January 7th, 2011 To: MPR Morning Edition Crew From: Mark Seeley, University of Minnesota Extension Dept of Soil, Water, and Climate Subject: Minnesota WeatherTalk Newsletter for Friday, January 7th, 2011 Headlines: -Cold continues -Overlooked feature of 2010 weather -Experimental Extreme Cold Warning -Weekly Weather Potpourri -MPR listener question -Almanac for January 7th -Past weather features -Feeding storms -Outlook Topic: Cold continues to start 2011 Following a colder than normal December, January is continuing the pattern as mean temperatures are averaging 5 to 9 degrees F colder than normal through the first week of the month. Minnesota has reported the coldest temperature in the 48 contiguous states four times so far this month, the coldest being -33 degrees F at Bigfork on the 3rd. In fact several places including Bemidji, International Falls, Bigfork, Babbit, and Cass Lake have recorded -30 degrees F or colder already this month. Temperatures are expected to continue colder than normal well into the third week of the month, with perhaps some moderation in temperature and a January thaw during the last ten days of the month. Topic: Overlooked feature of 2010 weather In my write-up and radio comments of last week about significant weather in 2010 several people mentioned that I overlooked the flash flood event in southern Minnesota over September 22-23, 2010 affecting at least 19 counties. One of the largest flash floods in history, this storm produced rainfall amounts greater than 10 inches in some places (11.06 inches near Winnebago) and near record flood crests on many Minnesota watersheds. -

Study on Typhoon Characteristic Based on Bridge Health Monitoring System

Hindawi Publishing Corporation e Scientific World Journal Volume 2014, Article ID 204675, 11 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/204675 Research Article Study on Typhoon Characteristic Based on Bridge Health Monitoring System Xu Wang,1 Bin Chen,2 Dezhang Sun,3 and Yinqiang Wu4 1 State Key Laboratory Breeding Base of Mountain Bridge and Tunnel Engineering, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing 400074, China 2 College of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China 3 Institute of Engineering Mechanics, China Earthquake Administration, Harbin 150080, China 4 Bureau of Public Works of Shenzhen Municipality, Shenzhen 518006, China Correspondence should be addressed to Dezhang Sun; [email protected] Received 25 March 2014; Revised 8 May 2014; Accepted 8 May 2014; Published 10 June 2014 Academic Editor: Ying Lei Copyright © 2014 Xu Wang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Through the wind velocity and direction monitoring system installed on Jiubao Bridge of Qiantang River, Hangzhou city, Zhejiang province, China, a full range of wind velocity and direction data was collected during typhoon HAIKUI in 2012. Based on these data, it was found that, at higher observed elevation, turbulence intensity is lower, and the variation tendency of longitudinal and lateral turbulence intensities with mean wind speeds is basically the same. Gust factor goes higher with increasing mean wind speed, and the change rate obviously decreases as wind speed goes down and an inconspicuous increase occurs when wind speed is high. -

Numerical Simulation of Tropical Cyclone Generated Waves in South China Sea During Winter Monsoon Surge Peng Qi1,2,3* & Aimei Wang4

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Numerical simulation of tropical cyclone generated waves in South China Sea during winter monsoon surge Peng Qi1,2,3* & Aimei Wang4 The South China Sea (SCS) is a highly semi-enclosed marginal sea located in the East Asian monsoon region. This paper proposes interesting aspects of the unique feature of the SCS waves in response to tropical cyclone’s passage when large-scale winter monsoon winds prevail. We use the wave model WaveWatch III to study the wave characteristics of typhoon Durian (2006) passing over the middle of SCS in early December 2006, and state the new understanding acquired in the aspects of the tropical cyclone generated waves in the SCS during winter monsoon surge. In light of this, the role of the large-scale NE monsoon winds on winter typhoon wave feld characteristics in the SCS are highlighted by conducting sensitivity experiments with and without the NE monsoon winds. The NE monsoon winds weakly afect the SWH feld near the typhoon track and strongly away from the track, especially in the deep water area of the northern SCS where the NE monsoon winds produce high waves. Comparisons between the two experiments show the efect of the NE monsoon winds on the directional wave spectra in the SCS, suggesting that the monsoon-generated swells do not decay and remain throughout the typhoon period. Te South China Sea (SCS) is located at 0°–23° N, 99° E–121° E, with a total area of about 3.5 × 106 km2. It is the largest and highly semi-enclosed marginal sea between the Asian continent to the north and the west, the Philip- pine islands to the east, and the Kalimantan (Borneo) to the south. -

Hong Kong Observatory Tracks of Tropical

/0 HONG KONG OBSERVATORY MUIFA #AUG TRACKS OF TROPICAL CYCLONES IN 2011 DE ROKE (), SEP !"# $ NO MERBOK BC Daily Positions at 00 UTC(08 HKT), AUG SONCA the number in the symbol represents 234 @A SEP the date of the month PQ TALAS MAON- NORU SEP JUL ,- SEP Intermediate 6-hourly Positions RS .)+' MEARI Super Typhoon JUN )+' Severe Typhoon +' Typhoon )* '( Severe Tropical Storm '( Tropical Storm % & Tropical Depression T.D. BJ AUG SONGDA TU FG MAY AERE KULAP MAY SEP 9:; NANMADOL KLM AUG T.D. SARIKA AUG Hong Kong JUN DE()1115 ROKE SEP NO()1110 MERBOK 56 AUG NESAT BC()1116 SEP PQ()1113 SONCA <= FG()1114 NORU SEP BANYAN KULAP SEP >@ OCT HAIMA SEP JUN DV HI NOCK- TEN HI()1119 @A()1106 NALGAE JUL NALGAE MAON- OCT >? SEP JUL HAITANG 9:;()1111 SEP 234(1112) NANMADOL 78 TALAS >?()1118 AUG KLM()1103 >@()1104 TOKAGE AUG HAITANG SARIKA HAIMA 78()1107 JUL SEP JUN JUN TOKAGE 56()1117 DV(1108) JUL NESAT NOCK- TEN SEP TU(1101) JUL AERE MAY RS(1105) MEARI JUN /0(1109) 1 MUIFA WASHI BJ(11 02) #JUL DEC SONGDA MAY <=()1120 BANYAN OCT 1()1121 WASHI DEC 二零一一年 熱 帶 氣 旋 TROPICAL CYCLONES IN 2011 2 二零一三年四月出版 Published April 2013 香港天文台編製 香港九龍彌敦道 134A Prepared by: Hong Kong Observatory 134A Nathan Road Kowloon, Hong Kong © 版權所有。未經香港天文台台長同意,不得翻印本刊物任何部分內容。 © Copyright reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the Director of the Hong Kong Observatory. 本刊物的編製和發表,目的是促進資 This publication is prepared and 料交流。香港特別行政區政府(包括 disseminated in the interest of promoting 其僱員及代理人) 對於本刊物所載資 the exchange of information. -

Typhoon in India and Taiwan

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 9, Issue 3 Ver. III (Mar. 2015), PP 27-32 www.iosrjournals.org Typhoon in India and Taiwan Smita Assistant Professor , Department of Geography, Lovely Professional University, Punjab. I. Introduction Tropical Cyclone is defined as a cyclonically rotating atmospheric vortex that ranges in diameter from a few hundred miles up to one or two thousand miles. It is associated with the central core of low pressure and convective clouds that are organized into spiral bands, with a sustained convective clouds mass at or near the centre. These are storms that originate in tropical latitudes; they include tropical depressions, tropical storms, hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones. Natural disasters cannot be controlled but they can be regulated and predicted to some extent. Similarly the origin and formation of Typhoons cannot be stopped, so the only way to handle this kind of disaster is through warning systems. A warning system can reduce the impact of the disaster and help to mitigate the impact. The devastation caused by tropical cyclones in terms of loss of lives and damage to the economics of all countries affected by these storms can be enormous. Damage estimates collected by the Typhoon Committee of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) have documented typhoon related economic losses exceeding 4 billion US dollars annually to the countries along the rim of the western north pacific (Chen 1995). Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) provides the Cyclone Warning System in India from the Area Cyclone Warning Centres (ACWC’s) at Kolkata, Chennai and Mumbai, and Cyclone Warning Centres (CWCs) at Bhubaneshwar, Vishakhapatnam and Ahmedabad. -

MEMBER REPORT (2013) China

MEMBER REPORT (2013) ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee 8th Integrated Workshop/2nd TRCG Forum China Macao, China 2 - 6 December 2013 CONTENTS I. Overview of Tropical Cyclones Which Have Affected/Impacted Members’ Area in 2013 1.1 Meteorological and Hydrological Assessment P. 1 1.2 Socio-Economic Assessment P.14 1.3 Regional Cooperation Assessment P.17 II. Summary of Advances in Key Result Areas Typhoon Forecast, Prediction and Research 2.1 Improvement of ensemble forecast-based bias correction method for typhoon track forecasts and establishment of seasonal typhoon quantitative prediction system P.20 2.2 Advances in numerical typhoon prediction models and data assimilation P.22 2.3 Advances in scientific research on typhoons P.24 Typhoon Observations, Satellite Application Platform and CMACast System 2.4 Ocean observing system and outfield typhoon observation experiment P.26 2.5 Improved calibrations methodology and satellite-based regional quick-scans P.28 2.6 Successful launch of FY-3C and deployment of SWAP platform P.30 2.7 Improved CMACast, WIS and MICAPS systems P.32 Disaster Prevention and Mitigation 2.8 Strategies and actions for typhoon preparedness of the China Meteorological Administration P.34 2.9 Anti-typhoon measures taken by the Ministry of Civil Affairs and their effectiveness P.36 2.10 Assessment and research on benefits from preparedness and reduction of typhoon-induced hazards, and typhoon risk mapping P.38 Hydrology 2.11 Reservoir water level monitoring and flood forecasting P.40 2.12 Regulations on publicizing hydrological early warning signals and relevant management P.42 Regional Cooperation 2.13 Regional joint efforts in response to super-typhoon HAIYAN (Yolanda) P.44 2.14 Activities in the Typhoon Committee Training Centre P.46 2.15 Application of the Xinanjiang hydrological model to the Segamat basin in Malaysia P.48 Appendix P.50 I. -

An Ontology Based Approach for Disaster Prediction

Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology 31 st May 2013. Vol. 51 No.3 © 2005 - 2013 JATIT & LLS. All rights reserved . ISSN: 1992-8645 www.jatit.org E-ISSN: 1817-3195 AN ONTOLOGY BASED APPROACH FOR DISASTER PREDICTION 1,2 YINGLONG MA, 1XIAO YU 1 School of Control and Computer Engineering, North China Electric Power University, Beijing 102206, China 2 State Key Laboratory of Computer, Institute of Software, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Natural disasters are those anomalies created by the nature in the process of the Earth. The harms they have caused to human society tend to be horrifying. Almost every country will be more or less affected by natural disasters annually. In consequence, giving a fairly accurate forecast of the disaster that may happen turns into a vital part of disaster prevention. Traditional research on disasters is mainly based on classical statistical methods or expertise judgment, which is lack of semantic-driven and intelligent reasoning. In this paper, an ontology based approach for disaster prediction was put forward. As the explicit specification of a conceptualization, ontologies can achieve a certain degree of knowledge sharing and reuse, and improve the system ability of communications, interoperability and reliability. On the basis of analyzing the influencing factors and historical evolution of disasters, a domain ontology model of natural disaster in OWL ontology language was created. The hidden influencing factors or disaster chain information can be excavated by the reasoner with domain-specific rules. As a result, we built an ontology-driven disaster prediction and information system.