China, Social Media, and Environmental Protest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This PDF File

Editor: Henry Reichman, California State University, East Bay Founding Editor: Judith F. Krug (1940–2009) Publisher: Barbara Jones Office for Intellectual Freedom, American Library Association ISSN 1945-4546 March 2013 Vol. LXII No. 2 www.ala.org/nif Filtering continues to be an important issue for most schools around the country. That was the message of the American Association of School Librarians (AASL), a division of the American Library Association, national longitudinal survey, School Libraries Count!, conducted between January 24 and March 4, 2012. The annual sur- vey collected data on filtering based on responses to fourteen questions ranging from whether or not their schools use filters, to the specific types of social media blocked at their schools. AASL survey The survey data suggests that many schools are going beyond the requirements set forth by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in its Child Internet Protection explores Act (CIPA). When asked whether their schools or districts filter online content, 98% of the respon- dents said content is filtered. Specific types of filtering were also listed in the survey, filtering encouraging respondents to check any filtering that applied at their schools. There were in schools 4,299 responses with the following results: • 94% (4,041) Use filtering software • 87% (3,740) Have an acceptable use policy (AUP) • 73% (3,138) Supervise the students while accessing the Internet • 27% (1,174) Limit access to the Internet • 8% (343) Allow student access to the Internet on a case-by-case basis The data indicates that the majority of respondents do use filtering software, but also work through an AUP with students, or supervise student use of online content individually. -

Copyright 2020. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. All Rights Reserved. May

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 7/21/2020 11:47 AM via CHINESE UNIV OF HONG KONG AN: 2486826 ; Guan Jun.; Silencing Chinese Media : The 'Southern Weekly' Protests and the Fate of Civil Society in Xi Jinping's China 1 Copyright 2020. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law. Account: s4314066.main.ehost Silencing Chinese Media The Southern Weekly Protests and the Fate of Civil Society in Xi Jinping’s China Guan Jun Translated by Kevin Carrico ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London EBSCOhost - printed on 7/21/2020 11:49 AM via CHINESE UNIV OF HONG KONG. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use 3 Published by Rowman & Littlefield An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 https://rowman.com 6 Tinworth Street, London SE11 5AL, United Kingdom Copyright © 2020 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Guan, Jun, (Journalist) author. | Carrico, Kevin, translator. Title: Silencing Chinese media : the “Southern Weekly” protests and the fate of civil society in Xi Jinping’s China / Guan Jun ; translated by Kevin Carrico. -

The Danger of Deconsolidation Roberto Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk Ronald F

July 2016, Volume 27, Number 3 $14.00 The Danger of Deconsolidation Roberto Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk Ronald F. Inglehart The Struggle Over Term Limits in Africa Brett L. Carter Janette Yarwood Filip Reyntjens 25 Years After the USSR: What’s Gone Wrong? Henry E. Hale Suisheng Zhao on Xi Jinping’s Maoist Revival Bojan Bugari¡c & Tom Ginsburg on Postcommunist Courts Clive H. Church & Adrian Vatter on Switzerland Daniel O’Maley on the Internet of Things Delegative Democracy Revisited Santiago Anria Catherine Conaghan Frances Hagopian Lindsay Mayka Juan Pablo Luna Alberto Vergara and Aaron Watanabe Zhao.NEW saved by BK on 1/5/16; 6,145 words, including notes; TXT created from NEW by PJC, 3/18/16; MP edits to TXT by PJC, 4/5/16 (6,615 words). AAS saved by BK on 4/7/16; FIN created from AAS by PJC, 4/25/16 (6,608 words). PGS created by BK on 5/10/16. XI JINPING’S MAOIST REVIVAL Suisheng Zhao Suisheng Zhao is professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver. He is executive director of the univer- sity’s Center for China-U.S. Cooperation and editor of the Journal of Contemporary China. When Xi Jinping became paramount leader of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 2012, some Chinese intellectuals with liberal lean- ings allowed themselves to hope that he would promote the cause of political reform. The most optimistic among them even thought that he might seek to limit the monopoly on power long claimed by the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). -

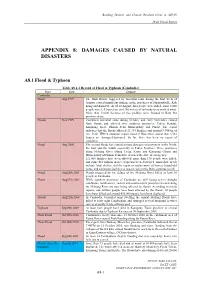

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Freedom of Expression

1 II. Human Rights FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION International Standards on Freedom of Expression The Chinese government and Communist Party continued to re- strict expression in contravention of international human rights standards, including Article 19 of the International Convenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.1 According to the ICCPR—which China signed 2 but has not ratified 3—and as reiterated in 2011 by the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression, countries may impose certain restrictions or limitations on freedom of expression, if such restrictions are provided by law and are necessary for the purpose of respecting the ‘‘rights or reputations of others’’ or protecting na- tional security, public order, public health, or morals.4 An October 2009 UN Human Rights Council resolution declared restrictions on the ‘‘discussion of government policies and political debate,’’ ‘‘peace- ful demonstrations or political activities, including for peace or de- mocracy,’’ and ‘‘expression of opinion and dissent’’ are inconsistent with Article 19(3) of the ICCPR.5 The UN Human Rights Com- mittee specified in a 2011 General Comment that restrictions on freedom of expression specified in Article 19(3) should be inter- preted narrowly and that the restrictions ‘‘may not put in jeopardy the right itself.’’ 6 Reinforcing Party Control Over the Media INSTITUTIONAL RESTRUCTURING OF PARTY AND GOVERNMENT AGENCIES In March 2018, the Chinese -

Tropical Cyclone Temperature Profiles and Cloud Macro-/Micro-Physical Properties Based on AIRS Data

atmosphere Article Tropical Cyclone Temperature Profiles and Cloud Macro-/Micro-Physical Properties Based on AIRS Data 1,2, 1, 3 3, 1, 1 Qiong Liu y, Hailin Wang y, Xiaoqin Lu , Bingke Zhao *, Yonghang Chen *, Wenze Jiang and Haijiang Zhou 1 1 College of Environmental Science and Engineering, Donghua University, Shanghai 201620, China; [email protected] (Q.L.); [email protected] (H.W.); [email protected] (W.J.); [email protected] (H.Z.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Severe Weather, Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Beijing 100081, China 3 Shanghai Typhoon Institute, China Meteorological Administration, Shanghai 200030, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (B.Z.); [email protected] (Y.C.) The authors have the same contribution. y Received: 9 October 2020; Accepted: 29 October 2020; Published: 2 November 2020 Abstract: We used the observations from Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) onboard Aqua over the northwest Pacific Ocean from 2006–2015 to study the relationships between (i) tropical cyclone (TC) temperature structure and intensity and (ii) cloud macro-/micro-physical properties and TC intensity. TC intensity had a positive correlation with warm-core strength (correlation coefficient of 0.8556). The warm-core strength increased gradually from 1 K for tropical depression (TD) to >15 K for super typhoon (Super TY). The vertical areas affected by the warm core expanded as TC intensity increased. The positive correlation between TC intensity and warm-core height was slightly weaker. The warm-core heights for TD, tropical storm (TS), and severe tropical storm (STS) were concentrated between 300 and 500 hPa, while those for typhoon (TY), severe typhoon (STY), and Super TY varied from 200 to 350 hPa. -

The Impact of Environmental Protests in the People's

RED SKIES: THE IMPACT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTESTS IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA, 2004-2016 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By PORTER LYONS Bachelors of Arts, University of Dayton, 2016 2018 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL 04/24/2018 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY PORTER LYONS ENTITLED RED SKIES: THE IMPACT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTESTS IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA, 2004-2016 BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS. Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Thesis Director Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Department of Political Science December Green, Ph.D. Department of Political Science Kathryn Meyer, Ph.D. Department of History Barry Milligan, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Lyons, Porter. M.A., Department of Political Science, Wright State University, 2018. Red Skies: The Impact of Environmental Protests in the People’s Republic of China, 2004-2016. How do increases in environmental protests in China impact increases in the implementation of environmental policies? Environmental protests in China are gaining traction. By examining these protests, this study analyzes forty-one protests and their impact on government enforcement of environmental regulations. Stratifying this study according to five areas (Beijing, Guangdong, Hunan, Jiangsu, and Sichuan), patterns began to emerge according to each area. Employing a framework William Gamson introduced (2009), this study analyzes the outcomes of environmental contention, including the use of co-optation and preemptive measures. -

Typhoon Effects on the South China Sea Wave Characteristics During Winter Monsoon

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2006-03 Typhoon effects on the South China Sea wave characteristics during winter monsoon Cheng, Kuo-Feng Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/2885 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS TYPHOON EFFECTS ON THE SOUTH CHINA SEA WAVE CHARACTERISTICS DURING WINTER MONSOON by CHENG, Kuo-Feng March 2006 Thesis Advisor: Peter C. Chu Second Reader: Timour Radko Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED March 2006 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE: Typhoon Effects on the South China Sea Wave 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Characteristics during Winter Monsoon 6. AUTHOR(S) Kuo-Feng Cheng 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION REPORT Monterey, CA 93943-5000 NUMBER 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Social Media Practices in China: Empowerment Through Subversive

Social Media Practices in China: Empowerment through Subversive Pleasure Minghua Wu Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Media The University of Adelaide April 2014 Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………..i List of Figures ................................................................................................................. vi List of Tables ................................................................................................................... ix Abstract ........................................................................................................................... xi Declaration .................................................................................................................... xiv Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... xvii CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Aims and Significance of this Project ..................................................................... 1 1.2 Research Questions .................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Power Shifts and Negotiations in Chinese Social Media ........................................ 5 1.4 Key Terms in Use in this -

Media at Risk Press Freedom in CHINA 2012-13 International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) 國際記者聯會 CONTENTS Residence Palace, Bloc C 155 Rue De La Loi 1

Media at Risk PRESS FREEDOM IN CHINA 2012-13 International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) 國際記者聯會 CONTENTS Residence Palace, Bloc C 155 Rue de la Loi 1. Preface 1 B-1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 235 22 00 2. Introduction 2 Fax: +32 2 235 22 19 Email: [email protected] http://www.ifj.org 3. China’s “Ice Age” – No end in sight 4 From Sacking Reporters to Distorting the Media Environment 13 IFJ Asia-Pacific In pain, but cheerful 19 國際記者聯會亞太區分會 245 Chalmers Street 4. Foreign Journalists in China under pressure 24 Redfern NSW 2016, Australia Tel: +61 2 9333 0999 Fax: +61 2 9333 0933 5. Hong Kong and Macaumedia fight back 28 Email: [email protected] Hong Kong Media Ecology Seen Through the Chief Executive and http://asiapacific.ifj.org Legislative Council Elections 34 6. Online Media 51 7. Recommendations 54 This report has been produced with partial financial assistance from the Alliance Safety and Solidarity Fund, which comprises contributions from journalist members of the Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance of Australia. 本報告之部份經費由澳洲媒體、娛樂與藝術聯會 屬下安全及團結基金贊助。 Author撰稿: Serenade Woo Editors 編輯: Katherine Bice, Katie Richmond & Minari Fernando Special Thanks to: Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China, Hong Kong Journalists Association, Hong Kong Press Photographers Association and The Associação dos Jornalistas de Macau 特別鳴謝: 駐華外國記者協會、香港記者協會、 香港攝影記者協會及澳門傳媒工作者協會 Cover caption: Three Hong Kong journalists were detained, criminally charged and assaulted by police in Hong Kong and Mainland when exercising their professional duties 封面圖片說明: 三名香港記者在履行專業採訪工 作時,分別被香港及大陸警察扣留、刑事檢控 及毆打。 MEDIA AT RISK: Press FreedOM IN CHINA 2012-13 PREFACE same time, the Chinese authorities immediately shut down he International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) initiated two international media outlets after they revealed some Ta program in early 2008 to monitor and report on press negative reports about the leaders of China. -

Appendix 3 Selection of Candidate Cities for Demonstration Project

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report APPENDIX 3 SELECTION OF CANDIDATE CITIES FOR DEMONSTRATION PROJECT Table A3-1 Long List Cities (No.1-No.62: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-1 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-2 Long List Cities (No.63-No.124: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-2 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-3 Long List Cities (No.125-No.186: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-3 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-4 Long List Cities (No.187-No.248: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-4 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-5 Long List Cities (No.249-No.310: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-5 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-6 Long List Cities (No.311-No.372: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. -

Mobilized by Mobile Media. How Chinese People Use Mobile Phones to Change Politics and Democracy Liu Jun

Mobilized by Mobile Media. How Chinese People use mobile phones to change politics and democracy Liu Jun To cite this version: Liu Jun. Mobilized by Mobile Media. How Chinese People use mobile phones to change politics and democracy. Social Anthropology and ethnology. University of Copenhagen. Faculty of Humanities, 2013. English. tel-00797157 HAL Id: tel-00797157 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00797157 Submitted on 5 Mar 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MOBILIZED BY MOBILE MEDIA HOW CHINESE PEOPLE USE MOBILE PHONES TO CHANGE POLITICS AND DEMOCRACY Jun Liu A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Faculty of Humanities University of Copenhagen August 2012 ACKNOWLEDGES First, I owe an unquantifiable debt to my dear wife, Hui Zhao, and my loving parents for their enduring support, trust, and encouragement for my study and research. Their unquestioning belief in my ability to complete my study was often the only inspiration and motivation I needed to keep me from succumbing to feelings of inadequacy and ineptitude. Second, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to Professor Klaus Bruhn Jensen, my supervisor.