Radio in the Public Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Ownership Rules

05-Sadler.qxd 2/3/2005 12:47 PM Page 101 5 MEDIA OWNERSHIP RULES It is the purpose of this Act, among other things, to maintain control of the United States over all the channels of interstate and foreign radio transmission, and to provide for the use of such channels, but not the ownership thereof, by persons for limited periods of time, under licenses granted by Federal author- ity, and no such license shall be construed to create any right, beyond the terms, conditions, and periods of the license. —Section 301, Communications Act of 1934 he Communications Act of 1934 reestablished the point that the public airwaves were “scarce.” They were considered a limited and precious resource and T therefore would be subject to government rules and regulations. As the Supreme Court would state in 1943,“The radio spectrum simply is not large enough to accommodate everybody. There is a fixed natural limitation upon the number of stations that can operate without interfering with one another.”1 In reality, the airwaves are infinite, but the govern- ment has made a limited number of positions available for use. In the 1930s, the broadcast industry grew steadily, and the FCC had to grapple with the issue of broadcast station ownership. The FCC felt that a diversity of viewpoints on the airwaves served the public interest and was best achieved through diversity in station ownership. Therefore, to prevent individuals or companies from controlling too many broadcast stations in one area or across the country, the FCC eventually instituted ownership rules. These rules limit how many broadcast stations a person can own in a single market or nationwide. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

Medicaid Member Handbook

Healthy Blue Member Handbook: Integrated Health Services For Physical and Behavioral Health Services 844-521-6941 (TTY 711) myhealthybluela.com 1007662LAMMLHBL 02/21 Healthy Blue Member Handbook: Integrated Health Services For Physical and Behavioral Health Services 844-521-6941 (TTY 711) 10000 Perkins Rowe, Suite G-510 Baton Rouge, LA 70810 myhealthybluela.com Revised: February 10, 2021 1007662LAMENHBL 02/21 HEALTHY BLUE QUICK GUIDE Read this quick guide to find out about: How to see a doctor and get medicines Choosing a primary care provider (PCP) The difference between routine medical care and an emergency Important phone numbers Renewing your benefits Seeing the doctor With Healthy Blue, you get a primary care provider (PCP). Your PCP is the family doctor or provider you’ll go to for routine and urgent care. When you enrolled you were given a PCP. To find or change a PCP, physical or behavioral health provider: Visit us online at myhealthybluela.com. Create a secure account by clicking “Register.” You’ll need your member ID number. Once you create an account, you’ll be able to choose your PCP online. Call Member Services at 844-521-6941 (TTY 711) Monday through Friday from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. To see the doctor, you can call his or her office directly and make an appointment. Don’t forget to bring your Healthy Blue member ID card with you. Medicines When you go to your PCP or another provider, you might get a prescription for medicine. You have pharmacy benefits as part of your Medicaid plan. -

Broadcast Television (1945, 1952) ………………………

Transformative Choices: A Review of 70 Years of FCC Decisions Sherille Ismail FCC Staff Working Paper 1 Federal Communications Commission Washington, DC 20554 October, 2010 FCC Staff Working Papers are intended to stimulate discussion and critical comment within the FCC, as well as outside the agency, on issues that may affect communications policy. The analyses and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the FCC, other Commission staff members, or any Commissioner. Given the preliminary character of some titles, it is advisable to check with the authors before quoting or referencing these working papers in other publications. Recent titles are listed at the end of this paper and all titles are available on the FCC website at http://www.fcc.gov/papers/. Abstract This paper presents a historical review of a series of pivotal FCC decisions that helped shape today’s communications landscape. These decisions generally involve the appearance of a new technology, communications device, or service. In many cases, they involve spectrum allocation or usage. Policymakers no doubt will draw their own conclusions, and may even disagree, about the lessons to be learned from studying the past decisions. From an academic perspective, however, a review of these decisions offers an opportunity to examine a commonly-asserted view that U.S. regulatory policies — particularly in aviation, trucking, and telecommunications — underwent a major change in the 1970s, from protecting incumbents to promoting competition. The paper therefore examines whether that general view is reflected in FCC policies. It finds that there have been several successful efforts by the FCC, before and after the 1970s, to promote new entrants, especially in the markets for commercial radio, cable television, telephone equipment, and direct broadcast satellites. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the NORTHERN DISTRICT of ALABAMA SOUTHERN DIVISION in RE: BLUE CROSS BLUE SHIELD ) Ma

Case 2:12-cv-02532-RDP Document 263 Filed 11/25/14 Page 1 of 162 FILED 2014 Nov-25 PM 03:40 U.S. DISTRICT COURT N.D. OF ALABAMA IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA SOUTHERN DIVISION IN RE: BLUE CROSS BLUE SHIELD ) Master File No. 2:13-CV-20000-RDP ANTITRUST LITIGATION ) (MDL No. 2406) ) This document relates to: ) THE PROVIDER TRACK _________________________________________ ) Jerry L. Conway, D.C., ) CORRECTED CONSOLIDATED Corey Musselman, M.D., ) SECOND AMENDED PROVIDER The San Antonio Orthopaedic Group, L.L.P., ) COMPLAINT Orthopaedic Surgery Center of San ) Antonio, L.P., ) Charles H. Clark III, M.D., ) Crenshaw Community Hospital, ) Bullock County Hospital, ) Fairhope Cosmetic Dentistry and Fresh ) Breath Center, P.C., ) Sports and Ortho, P.C., ) Kathleen Cain, M.D., ) Northwest Florida Surgery Center, L.L.C., ) Wini Hamilton, D.C., ) North Jackson Pharmacy, Inc., ) Neuromonitoring Services of America, Inc. ) Cason T. Hund, D.M.D., ) ProRehab, P.C., ) Texas Physical Therapy Specialists, L.L.C., ) BreakThrough Physical Therapy, Inc., ) Dunn Physical Therapy, Inc., ) Gaspar Physical Therapy, P.C., ) Timothy H. Hendlin, D.C., ) Greater Brunswick Physical Therapy, P.A., ) Charles Barnwell, D.C., ) Brain and Spine, L.L.C., ) Heritage Medical Partners, L.L.C., ) Judith Kanzic, D.C., ) Brian Roadhouse, D.C., ) Julie McCormick, M.D., L.L.C., ) Harbir Makin, M.D., ) Saket K. Ambasht, M.D., ) John M. Nolte, M.D., ) Bauman Chiropractic Clinic of Northwest ) Florida, P.A., ) Joseph S. Ferezy, D.C. d/b/a Ferezy Clinic of ) Case 2:12-cv-02532-RDP Document 263 Filed 11/25/14 Page 2 of 162 Chiropractic and Neurology, ) Snowden Olwan Psychological Services, ) Ear, Nose & Throat Consultants and Hearing ) Services, P.L.C., ) and ) U.S. -

Federal Communications Commission Record FCC 92-209

7 FCC Red No. 13 Federal Communications Commission Record FCC 92-209 Conclusion 42 Before the Federal Communications Commission Administrative Matters 43 Washington, D.C. 20554 Ordering Clause 54 MM Docket No. 91-221 Appendix A -- List of Commenters In the Matter of I. INTRODUCTION 1. This Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) proposes Review of the Commission's alternative means of lessening the regulatory burden on Regulations Governing Television television broadcasters as they seek to adapt to the Broadcasting multichannel video marketplace. As documented last year in the FCC Office of Plans and Policy's (OPP) wide ranging report on broadcast television and the rapidly NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING evolving market for video programming, 1 that market has undergone enormous changes over the period between Adopted: May 14, 1992; Released: June 12, 1992 1975 and 1990. In particular, the report found that the policies of the FCC and the entire federal government Comment Date: August 24, 1992 (e.g., the 1984 Cable Act) spawned new competition to Reply Comment Date: September 23, 1992 broadcast services that have resulted in a plethora of new services and choices for video consumers. The report fur ther suggested that these competitive forces were affecting By the Commission: Commissioner Duggan issuing a the ability of over-the-air television to contribute to a separate statement. diverse and competitive video programming marketplace. 2. The OPP report prompted us to release a Notice of 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Inquiry (N0/) and to seek comment on whether existing television ownership rules and related policies should be revised in order to allow television licensees greater flexi Paragraph bility to respond to enhanced competition in the distribu tion of video programming. -

American Broadcasting Company from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search for the Australian TV Network, See Australian Broadcasting Corporation

Scholarship applications are invited for Wiki Conference India being held from 18- <="" 20 November, 2011 in Mumbai. Apply here. Last date for application is August 15, > 2011. American Broadcasting Company From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search For the Australian TV network, see Australian Broadcasting Corporation. For the Philippine TV network, see Associated Broadcasting Company. For the former British ITV contractor, see Associated British Corporation. American Broadcasting Company (ABC) Radio Network Type Television Network "America's Branding Broadcasting Company" Country United States Availability National Slogan Start Here Owner Independent (divested from NBC, 1943–1953) United Paramount Theatres (1953– 1965) Independent (1965–1985) Capital Cities Communications (1985–1996) The Walt Disney Company (1997– present) Edward Noble Robert Iger Anne Sweeney Key people David Westin Paul Lee George Bodenheimer October 12, 1943 (Radio) Launch date April 19, 1948 (Television) Former NBC Blue names Network Picture 480i (16:9 SDTV) format 720p (HDTV) Official abc.go.com Website The American Broadcasting Company (ABC) is an American commercial broadcasting television network. Created in 1943 from the former NBC Blue radio network, ABC is owned by The Walt Disney Company and is part of Disney-ABC Television Group. Its first broadcast on television was in 1948. As one of the Big Three television networks, its programming has contributed to American popular culture. Corporate headquarters is in the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City,[1] while programming offices are in Burbank, California adjacent to the Walt Disney Studios and the corporate headquarters of The Walt Disney Company. The formal name of the operation is American Broadcasting Companies, Inc., and that name appears on copyright notices for its in-house network productions and on all official documents of the company, including paychecks and contracts. -

Trying to Promote Network Entry: from the Chain Broadcasting Rules to the Channel Occupancy Rule and Beyond

Trying to Promote Network Entry: From the Chain Broadcasting Rules to the Channel Occupancy Rule and Beyond Stanley M. Besen Review of Industrial Organization An International Journal Published for the Industrial Organization Society ISSN 0889-938X Volume 45 Number 3 Rev Ind Organ (2014) 45:275-293 DOI 10.1007/s11151-014-9424-1 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media New York. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Rev Ind Organ (2014) 45:275–293 DOI 10.1007/s11151-014-9424-1 Trying to Promote Network Entry: From the Chain Broadcasting Rules to the Channel Occupancy Rule and Beyond Stanley M. Besen Published online: 25 June 2014 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014 Abstract This article traces the efforts by the U.S. Federal Communications Com- mission to promote the entry of new networks, starting from its regulation of radio networks under the Chain Broadcasting Rules, through its regulation of broadcast television networks under its Financial Interest and Syndication Rules and its Prime Time Access Rule, and finally to its regulation of cable television networks under its Channel Occupancy and Leased Access Rules and its National Ownership Cap. -

Television Viewers -- Whether Or Not They Subscribe To

all television viewers -- whether or not they subscribe to cable. The exhibition of network programs by local outlets, which surround the network service with programming tailored to the audiences of their markets, increases both the reach and the attractiveness of the network. The affiliate's local news and other non-network programming contributes substantially to the success of adjacent network programs. We stress these obvious points only because they often tend to be ignored. The reality is that national broadcast networks need a successful partnership with their affiliates in today's video marketplace more than ever. It would be suicidal for them to abandon that partnership without adequate substitute. Any threat to do so in order to gain advantage in negotiations with an individual affiliate is simply not credible. 34 In sum, therefore, the supposed risk that a network might bypass its local affiliate in favor of cable distribution has no particular connection to network ownership .- 34 There is still another factor weighing against any attempt by a broadcast network to bypass local broadcast outlets in any market in favor of distribution of its service on a channel of an owned cable system. Pursuant to the Satellite Home Viewer Act of 1988 (17 U.S.C. §119 (1991», distributors of network-affiliated broadcast station signals to households with home satellite receivers enjoy a statutory copyright license, if the households which they serve lack access to a primary broadcast affiliate of the relevant network (over-the-air or via cable). A network that attempted to bypass its local affiliate would open the door (as a legal matter) to satellite-to-home distribution of its service in the market and would make that distribution of video services generally more competitive with its owned cable system. -

Fundraising Banquet Friday, October 20, 2017 Investment Management ®

Massachusetts Family Institute TS FAM ET ILY S IN U S H T C I A T S U S T A E M D Y E L D I I C M A A T F E established E D H T T O 1991 G S N T NI RENGTHE Twenty-Sixth Annual Fundraising Banquet Friday, October 20, 2017 Investment Management ® Breuer & Co. is pleased to support the Massachusetts Family Institute! ® LLC SCHOOL INFORMATION MANAGEMENT www.veracross.com Valetude® LLC HEALTHCARE SOFTWARE & SERVICES www.valetude.com ...providing software and service solutions for education and healthcare; serving organizations seeking highly tailored solutions with extraordinary levels of support. ǻŝŞŗǼȱŘŚŜȬŖŖŗŖȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱŝŖŗȱ ȱǰȱęǰȱȱŖŗŞŞŖȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱ ǯǯ Massachusetts Family Institute Twenty-Sixth Annual Fundraising Banquet Pledge of Allegiance National Anthem Michael Scully Invocation Father Darin Colarusso St. Athanasius Parish Greeting Todd Polando Massachusetts Family Institute Board Member Award Presentation David Aucoin AMEDAL- Asociacion Ministerial Evangelica Del Area de Lawrence Remarks Andrew Beckwith Massachusetts Family Institute President Introduction of Speaker Robert Bradley Massachusetts Family Institute Founder and Vice-Chairman Keynote Address Hugh Hewitt Closing Prayer Pastor Roberto Miranda Congregación León de Judá Dinner music performed by: Barry Johnston and Julianne Johnston 1 Dear Friends of the Family, Welcome to Massachusetts Family Institute’s 26th Anniversary Banquet. As a public policy organization, MFI attributes its success in strengthening families throughout the Commonwealth to the prayers and steadfast support of many partners. Therefore, tonight is a celebration of God’s great faithfulness in answering those prayers and effectively utilizing that support, enabling MFI to be the clarion voice for faith, family and freedom in the Bay State. -

By GC/MS -CIP Page

File: 18G 60 y~po D.B. ELELSON AIR FORCE BASE OPERABLE UINIT-2 SOURCE AREAS ST13/DP26 TREATABILITY STUDY INFORMAL TECHNqICAL INFORMATION REPORT VOLUME III: DATA EVALUATION AND VALIDATION REPORTS (FIELD ACTIVITIES ADDENDUM, APPENDIX E) FINAL MIR FORCE CENTER FOR ENVIRONMENTAL EXCELLENCE BROOKS MIR FORCE BASE, TEXAS FEBRUARY 16, 1996 MIR FORCE CENTER for ENVIRONMENTAL EXCELLENCE Source Areas ST13/DP26 Treatability Study Informal Technical Information Report Volume III: Data Evaluation and Validation Reports (Field Activities Addendum, Appendix B) Eielson Air Force Base, Alaska *0 February 16, 1996 FINAL Appendix E Data Evaluation and Validatdon Reports R112-96/ES/8840002.77AA Appendix E Data Quality Evaluation Elelson Afr Force Base Source Areas ST13/DP26 This appendix to the Field Activites Addendum presents the results of the Quality Assurance/ Quality Control (QA/QC) protocols implemented during the groundwater sampling and analysis portion of the site investigation. The quality indicators from every aspect of the data collections have been reviewed, and an assessment of the data with regard to the project specific objectives is presented. The reliability of the sampling and analytical procedures used during the investigation was demonstrated by implementing the project specific quality assurance procedures specified in the Quality Assurance Project Plan (QAPjP). Successful execution of these procedures provides strong supporting evidence for the acceptance of the data as being representative of the areas under investigation. A complete evaluation of the procedures implemented during the investigation are summarized in this Data Quality Evaluation (DQE). The DQE for the Source Areas ST13/DP26 Investigation was divided into two phases. The first phase includes the discussion of the overall field sampling effort and the field quality control (QC) activities employed. -

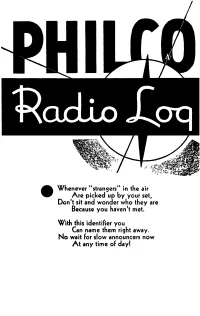

Philco Radio Log 1934

Whenever "strangers" in the air Are picked up by your set, Don't sit and wonder who they are Because you haven't met. With this identifier you Can name them right away. No wait for slow announcers now At any time of day! 50 75 100 150 200 250 300 500 750 1000 POWER 1500 2000 2500 1000 10000 15000 25000 50000 F G H I J K L M N 0 CODE P Q R 5 T U V W There are only 97 numbers on YOUR dial to accommodate more than 700 radio stations of North Amer ica. Stations at each number are listed MAP-LIKE beside 97 blank spaces. The 97 groups are in exact order, so, YOUR dial number recorded every 5th, or 10th, space enables you to estimate those skipped. To identify those heard by chance, station announcements will seldom be necessary. You can expect to hear stations of greater power, from greater distances. Note the letter at the extreme right and code above. *C:olumbla (WABC:) tNallonal Red (WEAF) .J.Natlonal Blue (WlZ) :J:Natlonal Red OR Blue Network Revision 40 1933-BY HAYNES' RADIO LOG Winter 1933 161 WEST HARRISON ST. CHICAGO, ILLINOIS WESTERN MIDDLE WESTERN Kilo D' I N CENTRAL EASTER'N WtI811 •• Ore •• Cal •• Utah. Etc. Minn., la., Neb., ~o .• Tez., Etc 14 o. Ilt, Mfch., OhiO, Tenn., Etc. MasS., N. Y., Pa .• N. Co.Btc. CFQC S.:skatoon. Sask ..... M 540 'CKLW Windsor-Detroit .... S ~~~~ ~~~~!lft~~b~e?::;~:·:~ r~~~RK:I~:"~~k~J.~~~: .~ 558---- ·WKRC Cincinnati. Ohlo...• O ·:::~lWa'te~b~ilvi·:::::~ *KLZ Den ver.