The Impact of the Fcc's Chain Broadcasting Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-22 Student Handbook

2021-2022 Property of:______________________________________________ Address:________________________________________________ Phone #:________________________________________________ In case of emergency, please notify: Name:___________________ Phone #:____________________ This Handbook & Planner is current as of July 2021, at the time of publication. Students and members of the College community are advised that any information contained in this handbook is subject to change at the discretion of the College. The College reserves the right to add, repeal, or amend any rules or regulations affecting students and any dates reported herein and once those changes are posted online, they are in effect. Students are encouraged to check online for the updated versions of all policies and procedures. In any such case, the College will provide appropriate notice as reasonable under the circumstances. Each student is expected to have knowledge of information contained in this handbook and in other college publications. Students are encouraged to check online at www.dc.edu for the updated versions of all policies and procedures. The information in this book was the best available at press time. Watch for additional information and changes. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form without getting prior written permission of the publisher. © 2021. SDI Innovations. All Rights Reserved. 2880 U.S. Hwy. 231 S. • Lafayette, IN 47909 • 765.471.8883 http://www.schooldatebooks.com • [email protected] 091122_5176 1 WELCOME TO DOMINICAN COLLEGE Dear Dominican College Student, It is with great pleasure that we take this opportunity to welcome you to Dominican Col- lege for the 2021-2022 Academic Year. -

DIRECT ECOMONIC IMPACT Larimer County Businesses and Individuals Contractors & Employees of Arise Music Festival

DIRECT ECOMONIC IMPACT Larimer County Businesses and Individuals Contractors & Employees of Arise Music Festival Business Address Town Action Signs PO Box 270096 Fort Collins Adrianne Beers 2200 Ouray Ct Fort Collins Alie Rich c/o Alie Rich Fort Collins Ally Biernat 624 S. Loomis St. Fort Collins Alya Sylla 328 Bimson Ave Berthoud American Eagle Distributing Co. 3800 Clydesdale Parkway Loveland Americas Variety Food Cart 3518 Worwick Drive Fort Collins Anika Hanson 216 Briarwood Dr. Fort Collins Aspyn Grading & Excavating Inc. PO Box 321 Laporte Big Al's Security Team 2649 E Mulberry St. Unit A11 Fort Collins Biodiesel For Bands, LLC 1609 Layland Ct. Fort Collins Blakesley Egan 306 W Laurel Street #412 Fort Collins Blue Grama c/o Kaite Meunier Fort Collins Bobby Ackerman 701 Larkbunting Drive Fort Collins Brian Tisa 1406 Laporte Ave. Fort Collins Cass Kruger 314 Scott Ave Fort Collins Chad Fisher Lineage Music Fort Collins Code 4 Security Services, LLC 1001 E. Harmony Rd., Suite A-21 Fort Collins Credentials For Events LLC 117 E 37TH ST # 426 Loveland Danamal 3812 Lynda Lane Fort Collins Daniel Holden 3812 Lynda Ln Fort Collins Dead Floyd,LLC 324 Remington St. #130 Fort Collins Eden Valley Institute of Wellness 9325 World Mission Drive Loveland Emissaries Of Divine Light Sunrise Ranch Loveland Ethan McKenty 116 E. Stuart street Fort Collins Flexx Productions 1833 E Harmony Rd #19 Fort Collins Fly Lo Bus Co 349 N. Shields Street Fort Collins Glen-Dix Inc. 850 Denver Ave Loveland Harry Backline,LLC 1814 Deep Woods Lane Fort Collins High Country Beverage Corporation 5706 Wright Drive Loveland Inland Leasing & Storage LLC P.O. -

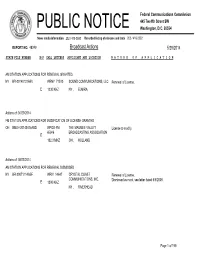

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

Media Ownership Rules

05-Sadler.qxd 2/3/2005 12:47 PM Page 101 5 MEDIA OWNERSHIP RULES It is the purpose of this Act, among other things, to maintain control of the United States over all the channels of interstate and foreign radio transmission, and to provide for the use of such channels, but not the ownership thereof, by persons for limited periods of time, under licenses granted by Federal author- ity, and no such license shall be construed to create any right, beyond the terms, conditions, and periods of the license. —Section 301, Communications Act of 1934 he Communications Act of 1934 reestablished the point that the public airwaves were “scarce.” They were considered a limited and precious resource and T therefore would be subject to government rules and regulations. As the Supreme Court would state in 1943,“The radio spectrum simply is not large enough to accommodate everybody. There is a fixed natural limitation upon the number of stations that can operate without interfering with one another.”1 In reality, the airwaves are infinite, but the govern- ment has made a limited number of positions available for use. In the 1930s, the broadcast industry grew steadily, and the FCC had to grapple with the issue of broadcast station ownership. The FCC felt that a diversity of viewpoints on the airwaves served the public interest and was best achieved through diversity in station ownership. Therefore, to prevent individuals or companies from controlling too many broadcast stations in one area or across the country, the FCC eventually instituted ownership rules. These rules limit how many broadcast stations a person can own in a single market or nationwide. -

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

The Don Lee-Columbia System

THE DON LEE-COLUMBIA SYSTEM: By Mike Adams 111 Sutter Street was not the only network broadcast address during the thirties. The other was 1000 Van Ness Avenue, the Don Lee Cadillac Building, headquarters for KFRC and the Don Lee-Columbia Network. It was there that another radio legend was born. Don Lee was a prominent Los Angeles automobile dealer, who had owned all the Cadillac and LaSalle dealerships in the State of California for over 20 years. After making a substantial fortune in the auto business, he decided to try his hand at broadcasting.1 In 1926, he purchased KFRC in San Francisco from the City of Paris department store. The following year he bought KHJ in Los Angeles and connected the two stations by telephone line to establish the Don Lee Broadcasting System. From the beginning, Lee spared no expense to make these two stations among the finest in the nation, as a 1929 article from Broadcast Weekly attests: Both KHJ and KFRC have large complete staffs of artists, singers and entertainers, with each station having its own Don Lee Symphony Orchestra, dance band and organ, plus all of the musical instruments that can be used successful in broadcasting. It is no idle boast that either KHJ or KFRC could operate continuously without going outside their own staffs for talent, and yet give a variety with an appeal to every type of audience.[2] In 1929, CBS still had no affiliates west of the Rockies, and this was making it difficult for the network to compete with its larger rival, NBC. -

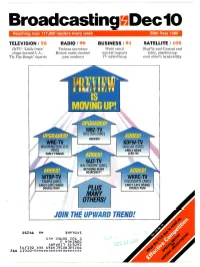

Broadcastingodec10 Reaching Over 117,000 Readers Every Week 60Th Year 1990

BroadcastingoDec10 Reaching over 117,000 readers every week 60th Year 1990 TELEVISION / 56 RADIO / 96 BUSINESS / 91 SATELLITE / 105 INTV: `Little train' Tribune examines Weak retail SkyPix and Comsat end chugs toward L.A.; British radio channel market impacts talks, questioning Tic Tac Dough' departs joint ventures TV advertising each other's bankability ' l WBZ -TV BOSTON (NBC) ACCESS! KDFW -TV DALLAS (CBS) EARLY NEWS LEAD -IN! WJZ -TV BALTIMORE (ABC) NETWORK NEWS DOW ADJACENCY! WISP -TV WKRC -TV TAMPA (ABC) CINCINNATI (ABC) EARLY -LATE FRINGE EARLY -LATE FRINGE DOUBLE RUN! PLUS DOUBLE RUN! MANY OTHERS! JOIN THE UPWARD TREND! 65266 VM 3NV)IOdS 3AV 3NOOfl ZO S 3 n VOV 7N05 AäV2l8I l At SU87 T6/030 )13A 68663qS0ä3E15266 266 I I01 G-f:********* * *, **= *w RELEASED FROM CROSBY LIBRARY GONZAGA UNIVERSITY I hear Warner Bros. is already on the road with something big in first-run for the fall. Is that so? r 1\2_1jrßr-á D2 has expanded the li It was only a matter of time. Now Sony D-2 Now it can cc composite digital video offers broadcasters some- thing they've been waiting for. Time compression. It's an option now available on the DVR -18, Sony's c three hour D -2 VTR. c The DVR -18's time With the DVR-18's optional time e compression, you can squeeze more out of the time you've got. e compression and expansion feature is remarkably advanced. A single plug -in module provides full audio data recovery as well as precise digital pitch correction for two stereo pairs of audio signals at The DVR -18 gives you ti the same time. -

The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: a Corporate Profile

Cornell University ILR School DigitalCommons@ILR Articles and Chapters ILR Collection 1-28-2004 The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Maria C. Figueroa Cornell University, [email protected] Damone Richardson Cornell University, [email protected] Pam Whitefield Cornell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/articles Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Arts Management Commons, and the Unions Commons Thank you for downloading an article from DigitalCommons@ILR. Support this valuable resource today! This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the ILR Collection at DigitalCommons@ILR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@ILR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If you have a disability and are having trouble accessing information on this website or need materials in an alternate format, contact [email protected] for assistance. The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Abstract [Excerpt] This research was commissioned by the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) with the expressed purpose of assisting the organization and its affiliate unions – which represent some 500,000 media and related workers – in understanding, more fully, the changes taking place in the arts and entertainment industry. Specifically, this report examines the impact that Clear Channel Communications, with its dominant positions in radio, live entertainment and outdoor advertising, has had on the industry in general, and workers in particular. Keywords AFL-CIO, media, worker, arts, entertainment industry, advertising, organization, union, marketplace, deregulation, federal regulators Disciplines Advertising and Promotion Management | Arts Management | Unions Comments Suggested Citation Figueroa, M. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

Acclaimed Journalist, Television Producer and Author Lisa Ling to Deliver Keynote Speech at MGM Resorts Foundation’S 11Th Annual Women’S Leadership Conference

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release Acclaimed Journalist, Television Producer and Author Lisa Ling to Deliver Keynote Speech at MGM Resorts Foundation’s 11th Annual Women’s Leadership Conference LAS VEGAS – May 30, 2017 – Lisa Ling, executive producer and host of the investigative documentary series “This is Life” on CNN, will speak at The MGM Resorts Foundation’s 11th annual Women’s Leadership Conference (WLC) Aug. 7-8 at MGM Grand Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas, NV. Ling, a best-selling author and one of the most respected and well-known investigative journalists in the industry, is expected to address a sell-out crowd at WLC 2017. The nonprofit conference is designed to inspire attendees to seek their highest level of personal and professional growth by presenting participants with inspiring role models, varying perspectives and strategies for development. Ling, who has reported from the farthest reaches of the planet, covering harrowing stories for The Oprah Winfrey Show, ABC News' Nightline and National Geographic's Explorer, will no doubt captivate audiences with her personal experiences, WLC 2017 organizers said. “Throughout her career, Lisa has traveled to some of the most dangerous locations in the world in an effort to bring social change through awareness and aid to those who need it most,” said Dawn Christensen, the conference's organizer and director of National Diversity Relations for MGM Resorts. “She is a champion of women and we are very excited to welcome her to the main stage at WLC 2017.” Over the past decade, WLC has grown in size, scope and reputation, drawing sellout crowds for the past three years. -

FY 2016 and FY 2018

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Appropriation Request and Justification FY2016 and FY2018 Submitted to the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee and the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee February 2, 2015 This document with links to relevant public broadcasting sites is available on our Web site at: www.cpb.org Table of Contents Financial Summary …………………………..........................................................1 Narrative Summary…………………………………………………………………2 Section I – CPB Fiscal Year 2018 Request .....……………………...……………. 4 Section II – Interconnection Fiscal Year 2016 Request.………...…...…..…..… . 24 Section III – CPB Fiscal Year 2016 Request for Ready To Learn ……...…...…..39 FY 2016 Proposed Appropriations Language……………………….. 42 Appendix A – Inspector General Budget………………………..……..…………43 Appendix B – CPB Appropriations History …………………...………………....44 Appendix C – Formula for Allocating CPB’s Federal Appropriation………….....46 Appendix D – CPB Support for Rural Stations …………………………………. 47 Appendix E – Legislative History of CPB’s Advance Appropriation ………..…. 49 Appendix F – Public Broadcasting’s Interconnection Funding History ….…..…. 51 Appendix G – Ready to Learn Research and Evaluation Studies ……………….. 53 Appendix H – Excerpt from the Report on Alternative Sources of Funding for Public Broadcasting Stations ……………………………………………….…… 58 Appendix I – State Profiles…...………………………………………….….…… 87 Appendix J – The President’s FY 2016 Budget Request...…...…………………131 0 FINANCIAL SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING’S (CPB) BUDGET REQUESTS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016/2018 FY 2018 CPB Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting requests a $445 million advance appropriation for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This is level funding compared to the amount provided by Congress for both FY 2016 and FY 2017, and is the amount requested by the Administration for FY 2018. -

Restoring Historical Understandings of the “Public Interest” Standard of American Broadcasting: an Exploration of the Fairness Doctrine

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), 89–109 1932–8036/20130005 Restoring Historical Understandings of the “Public Interest” Standard of American Broadcasting: An Exploration of the Fairness Doctrine CHRISTINA LEFEVRE–GONZALEZ University of Colorado, Boulder The “public interest” standard is a phrase that American broadcast regulation has not clearly defined throughout its history. Media scholars have attempted to locate the “true” meaning of the public interest standard by historicizing its use through broad analyses of broadcast regulation, but this approach has provided inadequate frameworks for understanding how the public interest standard has informed broadcast policy. By centering its historical analysis on the Fairness Doctrine, this article uncovers four dominant definitions for the public interest standard: first, as an enforcer of structure and efficiency of the spectrum; second, as part of the trusteeship of licensed broadcasters; third, for social justice and reform; and fourth, for the tastes and preferences of the public. The “public interest” is a phrase that, in the words of Richard Weaver (1953), possesses a “charismatic” quality. Political scientist Frank Sorauf (1957) described the concept as reflecting “the highest standard of governmental action, the measure of the greatest wisdom or morality in government” (p. 616). Some scholars believe that this idyllic phrase, an important rhetorical feature of American broadcast policy, possesses an indiscernible meaning that is susceptible to political will. Legal scholars Krattenmaker and Powe (1994) describe the standard as “either an empty concept or one that is infinitely manipulable” (p. 143). Zlotlow (2004) argues that the poorly defined standard “was both an empty concept and infinitely manipulable” (p.