The History of Wbap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Healthline Radio Show

HealthLine Radio Show Saturday Showtimes You can hear us in: Radio Station Time You can hear us in: Radio Station Time California, Los Angeles (and vicinity) KBRT 740 AM 9 to 9:30 a.m. (PST) New York, Rochester (and vicinity) WDCX 990 AM 12n to 1 p.m. (EST) California, Los Angeles (and vicinity) KKLA 99.5 FM 9 to 10 a.m. (PST) Ohio, Cleveland (and vicinity) WHK 1420 AM 12n to 1 p.m. (EST) California, Palm Springs (and vicinity) KMET 1490 AM 9 to 10 a.m. (PST) Ohio, Cleveland (and vicinity) WINT 1330 AM/101.5 FM 4 to 5 p.m. (EST) California, Sacramento (and vicinity) KFIA 710 AM 9 to 10 a.m. (PST) Oklahoma, Tulsa (and vicinity) KCFO 970 AM 10 to 11 a.m. (CST) California, San Diego (and vicinity) KPRZ 1210 AM/106.1 FM 11 to 12 noon (PST) Oregon, Portland (and vicinity) KKPZ 1330 AM 9 to 9:30 a.m. (PST) California, Ventura/Oxnard (and vicinity) KDAR 98.3 FM 9 to 10 a.m. (PST) Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (and vicinity) WNTP 990 AM 11 to 11:30 am (EST) Colorado, Denver (and vicinity) KLTT 670 AM 10 to 11 a.m. (MST) Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh (and vicinity) WPIT 730 AM 12n to 1 p.m. (EST) Indiana, Indianapolis (and vicinity) WBRI 1500 AM/96.7 FM 8 to 9 a.m. (CST) Pennsylvania, York (and vicinity) WYYC 1250 AM/98.1 FM 12n to 12:30 p.m. (EST) Iowa, Council Bluffs(and vicinity) KLNG 1560 AM 8:30 to 9 a.m. -

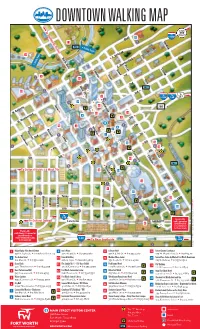

Downtown Walking Map

DOWNTOWN WALKING MAP To To121/ DFW Stockyards District To Airport 26 I-35W Bluff 17 Harding MC ★ Trinity Trails 31 Elm North Main ➤ E. Belknap ➤ Trinity Trails ★ Pecan E. Weatherford Crump Calhoun Grov Jones e 1 1st ➤ 25 Terry 2nd Main St. MC 24 ➤ 3rd To To To 11 I-35W I-30 287 ➤ ➤ 21 Commerce ➤ 4th Taylor 22 B 280 ➤ ➤ W. Belknap 23 18 9 ➤ 4 5th W. Weatherford 13 ➤ 3 Houston 8 6th 1st Burnett 7 Florence ➤ Henderson Lamar ➤ 2 7th 2nd B 20 ➤ 8th 15 3rd 16 ➤ 4th B ➤ Commerce ➤ B 9th Jones B ➤ Calhoun 5th B 5th 14 B B ➤ MC Throckmorton➤ To Cultural District & West 7th 7th 10 B 19 12 10th B 6 Throckmorton 28 14th Henderson Florence St. ➤ Cherr Jennings Macon Texas Burnett Lamar Taylor Monroe 32 15th Commerce y Houston St. ➤ 5 29 13th JANUARY 2016 ★ To I-30 From I-30, sitors Bureau To Cultural District Lancaster Vi B Lancaster exit Lancaster 30 27 (westbound) to Commerce ention & to Downtown nv Co From I-30, h exit Cherry / Lancaster rt Wo (eastbound) or rt Summit (westbound) I-30 To Fo to Downtown To Near Southside I-35W © Copyright 1 Major Ripley Allen Arnold Statue 9 Etta’s Place 17 LaGrave Field 25 Tarrant County Courthouse 398 N. Taylor St. TrinityRiverVision.org 200 W. 3rd St. 817.255.5760 301 N.E. 6th St. 817.332.2287 100 W. Weatherford St. 817.884.1111 2 The Ashton Hotel 10 Federal Building 18 Maddox-Muse Center 26 TownePlace Suites by Marriott Fort Worth Downtown 610 Main St. -

Ten Year Strategic Action Plan

PLANDOWNTOWN 2023 FORT WORTH TEN YEAR STRATEGIC ACTION PLAN 1 12 SH Uptown TRINITY Area ch ea W P UPTOWN S a 5 m u 3 e l - Trinity s H S I H Bluffs 19 9 M Northeast a in Edge Area Tarrant County t 1s Ex Courthouse Expansion d Area 3 2n rd EASTSIDE 3 h ap 4t lkn Be Downtown S f h P r C 5t H he at o U e e Core m n W d M m R e a e h r i r t s n c 6 o H e n o 2 u Southeast T s 8 h t th r o 7 o n 0 c k Edge Area m o h r t t 8 o n ITC h 9t CULTURAL 5th Expansion 7th 7th DISTRICT Burnett Area 2 Henderson- Plaza 10th vention Center Summit J City o n e Hall s Texas H C o e C m n h S d m e u e r e m r r r y s c m e o i n t Expansion Area 1 Lancaster J Lancaster e Lancaster n n i n g s d lv B k r a Holly P t s e Treatment IH-30 r o F Plant Parkview SOUTHEAST Area NEAR FORT SOUTHSIDE WORTH Table of Contents Message from Plan 2023 Chair 1 Executive Summary 2 The Plan 4 Vision 10 Business Development 16 Education 24 Housing 32 Retail, Arts and Entertainment 38 Transportation 42 Urban Design, Open Space and Public Art 50 Committee List, Acknowledgements 62 Message from Plan 2023 Chair Since the summer of 2003, Downtown Fort Worth has made advance - ments on many fronts. -

Radio Stations in Michigan Radio Stations 301 W

1044 RADIO STATIONS IN MICHIGAN Station Frequency Address Phone Licensee/Group Owner President/Manager CHAPTE ADA WJNZ 1680 kHz 3777 44th St. S.E., Kentwood (49512) (616) 656-0586 Goodrich Radio Marketing, Inc. Mike St. Cyr, gen. mgr. & v.p. sales RX• ADRIAN WABJ(AM) 1490 kHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-1500 Licensee: Friends Communication Bob Elliot, chmn. & pres. GENERAL INFORMATION / STATISTICS of Michigan, Inc. Group owner: Friends Communications WQTE(FM) 95.3 MHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-9500 Co-owned with WABJ(AM) WLEN(FM) 103.9 MHz Box 687, 242 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 263-1039 Lenawee Broadcasting Co. Julie M. Koehn, pres. & gen. mgr. WVAC(FM)* 107.9 MHz Adrian College, 110 S. Madison St. (49221) (517) 265-5161, Adrian College Board of Trustees Steven Shehan, gen. mgr. ext. 4540; (517) 264-3141 ALBION WUFN(FM)* 96.7 MHz 13799 Donovan Rd. (49224) (517) 531-4478 Family Life Broadcasting System Randy Carlson, pres. WWKN(FM) 104.9 MHz 390 Golden Ave., Battle Creek (49015); (616) 963-5555 Licensee: Capstar TX L.P. Jack McDevitt, gen. mgr. 111 W. Michigan, Marshall (49068) ALLEGAN WZUU(FM) 92.3 MHz Box 80, 706 E. Allegan St., Otsego (49078) (616) 673-3131; Forum Communications, Inc. Robert Brink, pres. & gen. mgr. (616) 343-3200 ALLENDALE WGVU(FM)* 88.5 MHz Grand Valley State University, (616) 771-6666; Board of Control of Michael Walenta, gen. mgr. 301 W. Fulton, (800) 442-2771 Grand Valley State University Grand Rapids (49504-6492) ALMA WFYC(AM) 1280 kHz Box 669, 5310 N. -

AROUND the HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition

NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM, INC. 25 Main Street, Cooperstown, NY 13326-0590 Phone: (607) 547-0215 Fax: (607)547-2044 Website Address – baseballhall.org E-Mail – [email protected] NEWS Brad Horn, Vice President, Communications & Education Craig Muder, Director, Communications Matt Kelly, Communications Specialist P R E S E R V I N G H ISTORY . H O N O R I N G E XCELLENCE . C O N N E C T I N G G ENERATIONS . AROUND THE HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition Sept. 17, 2015 volume 22, issue 8 FRICK AWARD BALLOT VOTING UNDER WAY The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Ford C. Frick Award is presented annually since 1978 by the Museum for excellence in baseball broadcasting…Annual winners are announced as part of the Baseball Winter Meetings each year, while awardees are presented with their honor the following summer during Hall of Fame Weekend in Cooperstown, New York…Following changes to the voting regulations implemented by the Hall of Fame’s Board of Directors in the summer of 2013, the selection process reflects an era-committee system where eligible candidates are grouped together by years of most significant contributions of their broadcasting careers… The totality of each candidate’s career will be considered, though the era in which the broadcaster is deemed to have had the most significant impact will be determined by a Hall of Fame research team…The three cycles reflect eras of major transformations in broadcasting and media: The “Broadcasting Dawn Era” – to be voted on this fall, announced in December at the Winter Meetings and presented at the Hall of Fame Awards Presentation in 2016 – will consider candidates who contributed to the early days of baseball broadcasting, from its origins through the early-1950s. -

Media Ownership Rules

05-Sadler.qxd 2/3/2005 12:47 PM Page 101 5 MEDIA OWNERSHIP RULES It is the purpose of this Act, among other things, to maintain control of the United States over all the channels of interstate and foreign radio transmission, and to provide for the use of such channels, but not the ownership thereof, by persons for limited periods of time, under licenses granted by Federal author- ity, and no such license shall be construed to create any right, beyond the terms, conditions, and periods of the license. —Section 301, Communications Act of 1934 he Communications Act of 1934 reestablished the point that the public airwaves were “scarce.” They were considered a limited and precious resource and T therefore would be subject to government rules and regulations. As the Supreme Court would state in 1943,“The radio spectrum simply is not large enough to accommodate everybody. There is a fixed natural limitation upon the number of stations that can operate without interfering with one another.”1 In reality, the airwaves are infinite, but the govern- ment has made a limited number of positions available for use. In the 1930s, the broadcast industry grew steadily, and the FCC had to grapple with the issue of broadcast station ownership. The FCC felt that a diversity of viewpoints on the airwaves served the public interest and was best achieved through diversity in station ownership. Therefore, to prevent individuals or companies from controlling too many broadcast stations in one area or across the country, the FCC eventually instituted ownership rules. These rules limit how many broadcast stations a person can own in a single market or nationwide. -

OKLAHOMA BOARD of NURSING 2915 North Classen Boulevard, Suite 524 Oklahoma City, OK 73106 405/962-1800 Third

Board Minutes November 16 & 17, 2005 Page 1 of 33 OKLAHOMA BOARD OF NURSING 2915 North Classen Boulevard, Suite 524 Oklahoma City, OK 73106 www.ok.gov/nursing 405/962-1800 Third Regular Meeting – November 16 & 17, 2005 FY2006 The Oklahoma Board of Nursing held its third regular meeting of FY2006 on November 16 & 17, 2005. Notice of the meeting was filed with the Secretary of State’s Office and notice/agenda was posted on the Oklahoma Board of Nursing web site. A notice/agenda was also posted on the Cameron Building front entrance at 2915 N. Classen, Oklahoma City, as well as the Board office, 2915 N. Classen, Suite 524, 24 hours prior to the meeting. Members present: Cynthia Foust, PhD, RN, President Jackye Ward, MS, RN, Vice-President Heather Sharp, LPN, Secretary-Treasurer Deborah Booton-Hiser, PhD, RN, ARNP Linda Coyer, LPN Teresa Frazier, MS, RN Lee Kirk, Public Member Melinda Laird, MS, RN Jan O’Fields, LPN Louise Talley, PhD, RN Roy Watson, PhD, Public Member Members absent: None Staff Present: Kim Glazier, MEd, RN, Executive Director Gayle McNish, EdD, MS, RN, Deputy Director of Regulatory Services Deborah J. Bruce, JD, Deputy Director of Investigative Division Laura Clarkson, RN, Peer Assistance Program Coordinator Darlene McCullock, CPM, Business Manager L. Louise Drake, MHR, RN, Associate Director of Nursing Practice Deborah Ball, RN, Nurse Investigator Lajuana Crossland, RN, Nurse Investigator Sandra Ellis, Executive Secretary Teena Jackson, Legal Secretary Shelley Rasco, Legal Secretary Andrea Story, Legal Secretary Legal Counsel Present: Charles C. Green, Attorney-at-Law Debbie McKinney, Attorney-at-Law Sue Wycoff, Attorney-at-Law Court Reporter: Susan Narvaez Word for Word Reporting, LLC 1 Board Minutes November 16 & 17, 2005 Page 2 of 33 1.0 Preliminary Activities The third regular meeting of FY2006 was called to order by Cynthia Foust, RN, PhD, Board President, at 8:00 a.m., on Wednesday, November 16, 2005, in the Holiday Inn Conference Center, 2101 S. -

Arizona Diamondbacks (1-2) at Texas Rangers (1-3) RHP Taijuan Walker (0-0, ––) Vs

Arizona Diamondbacks (1-2) at Texas Rangers (1-3) RHP Taijuan Walker (0-0, ––) vs. RHP Nick Martinez (0-0, ––) Spring #5 • Home #3 (0-2) • Tues., February 28, 2017 • Surprise Stadium • 2:05 p.m. CDT • Webcast TODAY’S SCHEDULED PITCHERS SPRING TRAINING AT A GLANCE TEXAS RANGERS ARIZONA 22 Nick Martinez RHP 99 Taijuan Walker RHP 65 Yohander Mendez LHP 61 Silvino Bracho RHP Record .......................................................................................1-3 74 Ariel Jurado RHP 47 Keyvius Sampson RHP Home .........................................................................................0-2 58 Alex Claudio LHP 53 Tyler Jones RHP Road ..........................................................................................1-1 *99 Anthony Carter RHP 67 Miller Diaz RHP *98 Sam Wolff RHP 72 Daniel Gibson LHP In Surprise .................................................................................1-2 62 Josh Taylor LHP Away from Surprise ...................................................................0-1 * - Minor league camp 65 Joey Krehbiel RHP Current streak ............................................................................. L2 Last 5 games .............................................................................1-3 TOMORROW’S SCHEDULED PITCHERS Longest winning streak ................................................................. 1 TEXAS RANGERS LOS ANGELES-AL Longest losing streak......................................................2 (current) 33 Martin Perez LHP 40 Jesse Chavez RHP TEX scores 1st/Opp. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

Medicaid Member Handbook

Healthy Blue Member Handbook: Integrated Health Services For Physical and Behavioral Health Services 844-521-6941 (TTY 711) myhealthybluela.com 1007662LAMMLHBL 02/21 Healthy Blue Member Handbook: Integrated Health Services For Physical and Behavioral Health Services 844-521-6941 (TTY 711) 10000 Perkins Rowe, Suite G-510 Baton Rouge, LA 70810 myhealthybluela.com Revised: February 10, 2021 1007662LAMENHBL 02/21 HEALTHY BLUE QUICK GUIDE Read this quick guide to find out about: How to see a doctor and get medicines Choosing a primary care provider (PCP) The difference between routine medical care and an emergency Important phone numbers Renewing your benefits Seeing the doctor With Healthy Blue, you get a primary care provider (PCP). Your PCP is the family doctor or provider you’ll go to for routine and urgent care. When you enrolled you were given a PCP. To find or change a PCP, physical or behavioral health provider: Visit us online at myhealthybluela.com. Create a secure account by clicking “Register.” You’ll need your member ID number. Once you create an account, you’ll be able to choose your PCP online. Call Member Services at 844-521-6941 (TTY 711) Monday through Friday from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. To see the doctor, you can call his or her office directly and make an appointment. Don’t forget to bring your Healthy Blue member ID card with you. Medicines When you go to your PCP or another provider, you might get a prescription for medicine. You have pharmacy benefits as part of your Medicaid plan. -

Stations Coverage Map Broadcasters

820 N. Capitol Ave., Lansing, MI 48906 PH: (517) 484-7444 | FAX: (517) 484-5810 Public Education Partnership (PEP) Program Station Lists/Coverage Maps Commercial TV I DMA Call Letters Channel DMA Call Letters Channel Alpena WBKB-DT2 11.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOOD-TV 7 Alpena WBKB-DT3 11.3 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOTV-TV 20 Alpena WBKB-TV 11 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXSP-DT2 15.2 Detroit WKBD-TV 14 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXSP-TV 15 Detroit WWJ-TV 44 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXMI-TV 19 Detroit WMYD-TV 21 Lansing WLNS-TV 36 Detroit WXYZ-DT2 41.2 Lansing WLAJ-DT2 25.2 Detroit WXYZ-TV 41 Lansing WLAJ-TV 25 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-DT2 12.2 Marquette WLUC-DT2 35.2 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-DT3 12.3 Marquette WLUC-TV 35 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-TV 12 Marquette WBUP-TV 10 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WBSF-DT2 46.2 Marquette WBKP-TV 5 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WEYI-TV 30 Traverse City-Cadillac WFQX-TV 32 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOBC-CA 14 Traverse City-Cadillac WFUP-DT2 45.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOGC-CA 25 Traverse City-Cadillac WFUP-TV 45 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOHO-CA 33 Traverse City-Cadillac WWTV-DT2 9.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOKZ-CA 50 Traverse City-Cadillac WWTV-TV 9 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOLP-CA 41 Traverse City-Cadillac WWUP-DT2 10.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOMS-CA 29 Traverse City-Cadillac WWUP-TV 10 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOOD-DT2 7.2 Traverse City-Cadillac WMNN-LD 14 Commercial TV II DMA Call Letters Channel DMA Call Letters Channel Detroit WJBK-TV 7 Lansing WSYM-TV 38 Detroit WDIV-TV 45 Lansing WILX-TV 10 Detroit WADL-TV 39 Marquette WJMN-TV 48 Flint-Saginaw-Bay -

Chapter 11 ) CITADEL BROADCASTING CORPORATION, Et Al., ) Case No

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) CITADEL BROADCASTING CORPORATION, et al., ) Case No. 09-17442 (BRL) ) Debtors. ) Jointly Administered ) FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER CONFIRMING THE SECOND MODIFIED JOINT PLAN OF REORGANIZATION OF CITADEL BROADCASTING CORPORATION AND ITS DEBTOR AFFILIATES PURSUANT TO CHAPTER 11 OF THE BANKRUPTCY CODE The Second Modified Joint Plan of Reorganization of Citadel Broadcasting Corporation and its Debtor Affiliates Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code, dated May 10, 2010, a copy of which is annexed hereto as Exhibit 1 and incorporated herein by reference (the “Plan”),1 having been filed with the Court by Citadel Broadcasting Corporation (“Citadel”) and its debtor affiliates, as debtors and debtors in possession (collectively, the “Debtors”);2 and the Court 1 Capitalized terms used but not otherwise defined herein shall have the meanings ascribed to such terms in the Plan. The Joint Plan of Reorganization of Citadel Broadcasting and Its Debtor Affiliates Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code was filed on February 3, 2010 [Docket No. 110]; the First Modified Joint Plan of Reorganization of Citadel Broadcasting and Its Debtor Affiliates Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code was filed on March 15, 2010 [Docket No. 198]. 2 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases are: Alphabet Acquisition Corp.; Atlanta Radio, LLC; Aviation I, LLC; Chicago FM Radio Assets, LLC; Chicago License, LLC; Chicago Radio Assets, LLC; Chicago Radio Holding,