Download PDF Datastream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme

Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy Volume 6 Article 4 1-1-1998 Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme Kimberly J. Pierson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/circles Part of the Law Commons, and the Legal Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pierson, Kimberly J. (1998) "Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme," Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy: Vol. 6 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/circles/vol6/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIRCLES 1998 Vol. VI REVENGE AND PUNISHMENT: LEGAL PROTOTYPE AND FAIRY TALE THEME By Kimberly J. Pierson' The study of the interrelationship between law and literature is currently very much in vogue, yet many aspects of it are still relatively unexamined. While a few select works are discussed time and time again, general children's literature, a formative part of a child's emerging notion of justice, has been only rarely considered, and the traditional fairy tale2 sadly ignored. This lack of attention to the first examples of literature to which most people are exposed has had a limiting effect on the development of a cohesive study of law and literature, for, as Ian Ward states: It is its inter-disciplinary nature which makes children's literature a particularly appropriate subject for law and literature study, and it is the affective importance of children's literature which surely elevates the subject fiom the desirable to the necessary. -

On the Passions of Kings: Tragic Transgressors of the Sovereign's

ON THE PASSIONS OF KINGS: TRAGIC TRANSGRESSORS OF THE SOVEREIGN’S DOUBLE BODY IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY FRENCH THEATRE by POLLY THOMPSON MANGERSON (Under the Direction of Francis B. Assaf) ABSTRACT This dissertation seeks to examine the importance of the concept of sovereignty in seventeenth-century Baroque and Classical theatre through an analysis of six representations of the “passionate king” in the tragedies of Théophile de Viau, Tristan L’Hermite, Pierre Corneille, and Jean Racine. The literary analyses are preceded by critical summaries of four theoretical texts from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in order to establish a politically relevant definition of sovereignty during the French absolutist monarchy. These treatises imply that a king possesses a double body: physical and political. The physical body is mortal, imperfect, and subject to passions, whereas the political body is synonymous with the law and thus cannot die. In order to reign as a true sovereign, an absolute monarch must reject the passions of his physical body and act in accordance with his political body. The theory of the sovereign’s double body provides the foundation for the subsequent literary study of tragic drama, and specifically of king-characters who fail to fulfill their responsibilities as sovereigns by submitting to their human passions. This juxtaposition of political theory with dramatic literature demonstrates how the king-character’s transgressions against his political body contribute to the tragic aspect of the plays, and thereby to the -

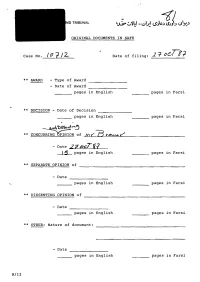

Page 1 MS TRIBUNAL ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS in SAFE Case No

MS TRIBUNAL ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS IN SAFE Case No. / CJ f / 2.. Date of filing: ). '=1- oe,,,,Tf:; ** AWARD - Type of Award -------- - Date of Award ----------- ---- pages in English ---- pages in Farsi "'' ** DECISION - Date of Decision pages in English pages in Farsi .. "'~ ~\S5c n·b~ ** CONCU~Nof M < ]3 r ~ v - Date 2 7 e,tt:,/ 'i ·2 15 pages in English pages in Farsi ** SEPARATE OPINION of - Date 'lo,, pages in English pages in Farsi ** DISSENTING OPINION of - Date pages in English pages in Farsi ** OTHER1 Nature of document: - Date --- pages in English ---- pages in Farsi R/12 .. !RAN-UNITED ST ATES CLAIMS TRIBUNAL ~ ~~\,\- - \:J\r\- l>J~.> c.S.J.,,.> ~~.) CASE NO.10712 CHAMBER THREE AWARD NO.321-10712-3 IUH UNITEO lffATIII J,1. • ..r;.11 J .!! JI• &AIMS TRIBUNAi: a...,_.:,'i~l__,~I HARRINGTON AND ASSOCIATES, INC., a: - ... a claim of less than U.S.$250,000 FILED • ~.l--•I ~ presented by the ... 2 7 0 CT 1987 c-.-1: UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, 1iff /A/ a Claimant, and 10 7 1 2 THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN, Respondent. CONCURRING AND DISSENTING OPINION OF JUDGE BROWER 1. This Award regrettably perpetuates the schizophrenia which from the Tribunal's inception has characterized its approach towards the belated specification of parties. 2. The first episode was the Tribunal's action in accept ing for filing a claim lodged against Iranian respondents by "AMF Overseas Corporation (Swiss Company) (wholly owned subsidiary of AMF Inc.)," notwithstanding the complete absence of any allegation in the Statement of Claim regard- ing the nationality -

495 the Honorable Paul W. Grimm* & David

A PRAGMATIC APPROACH TO DISCOVERY REFORM: HOW SMALL CHANGES CAN MAKE A BIG DIFFERENCE IN CIVIL DISCOVERY The Honorable Paul W. Grimm & David S. Yellin I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 495 II. INSTITUTIONAL PROBLEMS IN CIVIL PRACTICE .......................................... 501 A. The Vanishing Jury Trial ..................................................................... 501 B. A Lack of Active Judicial Involvement ................................................. 505 C. The Changing Nature of Discovery ..................................................... 507 1. The Growth of Discovery Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ...................................................................................... 508 2. The Expansion in Litigation .......................................................... 510 3. The Advent of E-Discovery ........................................................... 511 III. PROPOSED REFORMS TO CIVIL DISCOVERY ................................................ 513 A. No. 1. Excessively Broad Scope of Discovery ...................................... 514 B. No. 2. Producing Party Pays vs. Requesting Party Pays ..................... 520 C. No. 3. The Duty to Cooperate During Discovery ................................ 524 IV. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................... 533 I. INTRODUCTION In 2009, the American Bar Association (ABA) Section of Litigation conducted a survey -

Alexandre Dumas His Life and Works

f, t ''m^t •1:1^1 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNDERGRADUATE LIBRARY tu U X'^S>^V ^ ^>tL^^ IfO' The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924014256972 ALEXANDRE DUMAS HIS LIFE AND WORKS ALEXANDRE DUMAS (pere) HIS LIFE AND WORKS By ARTHUR F. DAVIDSON, M.A (Formerly Scholar of Keble College, Oxford) "Vastus animus immoderata, incredibilia, Nimis alta semper cupiebat." (Sallust, Catilina V) PHILADELPHIA J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY Ltd Westminster : ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO 1902 Butler & Tanner, The Selwood Printing Works, Frome, and London. ^l&'il^li — Preface IT may be—to be exact, it is—a somewhat presumptuous thing to write a book and call it Alexandre Dumas. There is no question here of introducing an unknown man or discovering an unrecognized genius. Dumas is, and has been for the better part of a century, the property of all the world : there can be little new to say about one of whom so much has already been said. Remembering also, as I do, a dictum by one of our best known men of letters to the effect that the adequate biographer of Dumas neither is nor is likely to be, I accept the saying at this moment with all the imfeigned humility which experience entitles me to claim. My own behef on this point is that, if we could conceive a writer who combined in himself the anecdotal facility of Suetonius or Saint Simon, with the loaded brevity of Tacitus and the judicial irony of Gibbon, such an one might essay the task with a reasonable prospect of success—though, after all, the probability is that he would be quite out of S5nnpathy with Dumas. -

DUMITRU IUGA Studii Şi Alte Scrieri

Dumitru Iuga - studii úi alte scrieri DUMITRU IUGA studii úi alte scrieri Editura CYBELA, 2015 1 Dumitru Iuga - studii úi alte scrieri Carte publicată cu sprijinul financiar al Consiliului JudeĠean Maramureú, în cadrul Programului JudeĠean pentru finanĠare nerambursabilă din bugetul judeĠean al programelor, proiectelor úi acĠiunilor culturale pe anul 2015. Tehnoredactare: Dumitru Iuga, Raul Laza Coperta I: Pomul vieĠii, cu pasărea Măiastră. Sec. XVIII. Stâlp de poartă din Maramureú. Foto: Francisc Nistor. Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii NaĠionale a României IUGA, DUMITRU studii úi alte scrieri/Dumitru Iuga; - Baia Mare: CYBELA ISBN 10 973-8126-28-2 ISBN 13 978-973- 8126- 28 - 2 ConĠinutul acestui volum nu reprezintă în mod necesar punctul de vedere al finanĠatorului, sau al Editurii CYBELA. 2 Dumitru Iuga - studii úi alte scrieri studii L O C A L I T Ă ğ I L E din ğ A R A M A R A M U R E ù U L U I în secolul XIV Maramureúul de dincoace de Tisa, de la Muntele Bârjaba până la Huta, cât a mai rămas în România după primul război mondial, este abia a treia parte din vechea Terra Maramorosiensis care se întindea de la Obcinele Bucovinei până la Talabârjaba úi dincolo de cetatea Hust. În satul Iza, situat la cîĠiva kilometri de această poartă a Tisei spre Vest, s-au făcut importante descoperiri arheologice datând din mileniul volburării de popoare spre inima Europei o Ġară înconjurată úi apărată de zidurile munĠilor Rodnei, ğibleú, Gutâi, Oaú, Bârjabei úi, margine spre vechea PocuĠie, GaliĠia úi Bucovina, munĠii Maramureúului úi CarpaĠii Păduroúi. -

![Miranda, 15 | 2017, « Lolita at 60 / Staging American Bodies » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 18 Septembre 2017, Consulté Le 16 Février 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3845/miranda-15-2017-%C2%AB-lolita-at-60-staging-american-bodies-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-18-septembre-2017-consult%C3%A9-le-16-f%C3%A9vrier-2021-2203845.webp)

Miranda, 15 | 2017, « Lolita at 60 / Staging American Bodies » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 18 Septembre 2017, Consulté Le 16 Février 2021

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 15 | 2017 Lolita at 60 / Staging American Bodies Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10470 DOI : 10.4000/miranda.10470 ISSN : 2108-6559 Éditeur Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Référence électronique Miranda, 15 | 2017, « Lolita at 60 / Staging American Bodies » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 18 septembre 2017, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10470 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/miranda.10470 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 SOMMAIRE Les 60 ans de Lolita Introduction Marie Bouchet, Yannicke Chupin, Agnès Edel-Roy et Julie Loison-Charles Nabokov et la censure Julie Loison-Charles Lolita, le livre « impossible » ? L'histoire de sa publication française (1956-1959) dans les archives Gallimard Agnès Edel-Roy Fallait-il annoter Lolita? Suzanne Fraysse The patterning of obsessive love in Lolita and Possessed Wilson Orozco Publicités, magazines, et autres textes non littéraires dans Lolita : pour une autre poétique intertextuelle Marie Bouchet Solipsizing Martine in Le Roi des Aulnes by Michel Tournier: thematic, stylistic and intertextual similarities with Nabokov's Lolita Marjolein Corjanus Les « Variations Dolores » - 2010-2016 Nouvelles lectures-réécritures de Lolita Yannicke Chupin Staging American Bodies Staging American Bodies – Introduction Nathalie Massip Spectacle Lynching and Textual Responses Wendy Harding Bodies of War and Memory: Embodying, Framing and Staging the Korean War in the United States Thibaud Danel Singing and Painting the Body: Walt Whitman and Thomas Eakins’ Approach to Corporeality Hélène Gaillard “It’s so queer—in the next room”: Docile/ Deviant Bodies and Spatiality in Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour Sarah A. -

August 27, 2013 Dear Tax Tribunal Practitioner

STATE OF MICHIGAN RICK SNYDER DEPARTMENT OF LICENSING AND REGULATORY AFFAIRS STEVE ARWOOD GOVERNOR DIRECTOR MICHIGAN ADMINISTRATIVE HEARING SYSTEM MICHAEL ZIMMER EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR August 27, 2013 Dear Tax Tribunal Practitioner: As a result of the abuse of the Tribunal’s current prehearing and show cause process, the Tribunal will be modifying that process effective with valuation disclosures and prehearing statements due after October 1, 2013. Although parties are given notice and a sufficient opportunity to conduct discovery, discuss settlement, and prepare their valuation disclosures and prehearing statements for timely submission, most parties fail to file their valuation disclosures and prehearing statements by the dates established in the Prehearing General Call and Orders of Procedure. Rather, parties wait until the prehearing conference to submit their valuation disclosures and prehearing statements, which requires the Tribunal to commence the prehearing conference as a show cause hearing to determine whether those parties should be permitted to offer their untimely valuation disclosure for admission or witnesses to testify. See TTR 231 and 237. See also MCL 205.732. Such decisions are not easily made as they could preclude or otherwise prevent parties from presenting their case and potentially impact the timely resolution of cases. As a result, the Tribunal will no longer be conducting show cause hearings. Instead, the Tribunal will be issuing orders holding parties in default for failing to timely file and exchange their valuation disclosures and prehearing statements. Further, the Tribunal will be treating such failures as establishing a history of deliberate delay, given the notice and opportunity provided to prepare valuation disclosures and prehearing statements for timely submission. -

EXT. PARIS. TREE LINED AVENUE. DAY Dawn Mist Lingers in the Air

EXT. PARIS. TREE LINED AVENUE. DAY Dawn mist lingers in the air. D’ARTAGNAN stands at one end, in his shirtsleeves, his sword drawn, a dagger in his other hand. ATHOS, PORTHOS and ARAMIS gather around him. Opposite them is PRIDEUX, his sword at the ready. ARAMIS eyes PRIDEUX with cool respect then pats D’ARTAGNAN on the shoulder. ARAMIS What's the vital thing to remember in a duel? D'ARTAGNAN Honour? PORTHOS cuffs him on the back of the head. PORTHOS Not getting killed. Right, biting, kicking, gouging. It's all good. ATHOS leans in to talk quietly to D’ARTAGNAN. ATHOS You don't have to do this. It's Musketeer business. D'ARTAGNAN I can handle it. He hands ATHOS his glove, ATHOS takes it, steps back and holds it poised. Even before ATHOS drops it to the ground, PRIDEUX launches a furious assault. As PRIDEUX comes at him he spins and cracks his arm at the elbow, making D’ARTAGNAN drop the dagger. D’ARTAGNAN manages a few blows with his sword but, PRIDEUX punches him in the face, sending him sprawling in the dirt, then kicks him in the head. He moves in for the kill but D'ARTAGNAN rallies with an eye- watering kick in the balls. PORTHOS beams proudly and turns to ARAMIS. PORTHOS I taught him that move. (CONTINUED) 2. CONTINUED: D'ARTAGNAN staggers to his feet. Swords clash, early morning sun flashing off the blades. Both men pant for breath, sweating despite the cold. ATHOS watches intently, whilst PORTHOS giggles. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 117/Tuesday, June 22, 2021/Rules and Regulations

Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 117 / Tuesday, June 22, 2021 / Rules and Regulations 32637 requirements, Security measures, DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION in light of the Supreme Court decision Waterways. discussed below. 34 CFR Chapter I In 2020, the Supreme Court in For the reasons discussed in the Bostock v. Clayton County, 140 S. Ct. preamble, the Coast Guard amends 33 Enforcement of Title IX of the 1731, 590 U.S. ll (2020), concluded CFR part 165 as follows: Education Amendments of 1972 With that discrimination based on sexual Respect to Discrimination Based on orientation and discrimination based on PART 165—REGULATED NAVIGATION Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity gender identity inherently involve AREAS AND LIMITED ACCESS AREAS in Light of Bostock v. Clayton County treating individuals differently because AGENCY: of their sex. It reached this conclusion ■ Office for Civil Rights, 1. The authority citation for part 165 Department of Education. in the context of Title VII of the Civil continues to read as follows: Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 ACTION: Interpretation. Authority: 46 U.S.C. 70034, 70051; 33 CFR U.S.C. 2000e et seq., which prohibits 1.05–1, 6.04–1, 6.04–6, and 160.5; SUMMARY: The U.S. Department of sex discrimination in employment. As Department of Homeland Security Delegation Education (Department) issues this noted below, courts rely on No. 0170.1. interpretation to clarify the interpretations of Title VII to inform Department’s enforcement authority interpretations of Title IX. ■ 2. Add § 165.T11–057 to read as over discrimination based on sexual The Department issues this follows: orientation and discrimination based on Interpretation to make clear that the gender identity under Title IX of the Department interprets Title IX’s § 165.T11–057 Safety Zone; Southwest Education Amendments of 1972 in light prohibition on sex discrimination to Shelter Island Channel Entrance Closure, of the Supreme Court’s decision in encompass discrimination based on San Diego, CA. -

Primacy's Twilight? on the Legal

STUDY Requested by the AFCO committee Primacy’s Twilight? On the Legal Consequences of the Ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court of 5 May 2020 for the Primacy of EU Law Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs Directorate-General for Internal Policies PE 692.276 - April 2021 EN Primacy’s Twilight? On the Legal Consequences of the Ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court of 5 May 2020 for the Primacy of EU Law Abstract This study, commissioned by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the AFCO Committee, analyses the repercussions of the judgment of the German Federal Constitutional Court of 5 May 2020. It puts the decision into context, makes a normative assessment, analyses the potential consequences and makes some policy recommendations. This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs. AUTHORS Niels PETERSEN and Konstantin CHATZIATHANASIOU, Institute for International and Comparative Public Law, University of Münster ADMINISTRATOR RESPONSIBLE Udo BUX EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Christina KATSARA LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE EDITOR Policy departments provide in-house and external expertise to support EP committees and other par- liamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny over EU internal policies. To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe for updates, please write to: Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs European Parliament B-1047 Brussels Email: [email protected] Manuscript completed in April 2021 © European Union, 2021 This document is available on the internet at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analyses DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not neces- sarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.