495 the Honorable Paul W. Grimm* & David

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to Present

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to present 2014 Medal Winner: Locomotive, written and illustrated by Brian Floca (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing) 2014 Honor Books: Journey, written and illustrated by Aaron Becker (Candlewick Press) Flora and the Flamingo, written and illustrated by Molly Idle (Chronicle Books) Mr. Wuffles! written and illustrated by David Wiesner (Clarion Books, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing) 2013 Medal Winner: This Is Not My Hat, written and illustrated by Jon Klassen (Candlewick Press) 2013 Honor Books: Creepy Carrots!, illustrated by Peter Brown, written by Aaron Reynolds (Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division) Extra Yarn, illustrated by Jon Klassen, written by Mac Barnett (Balzer + Bray, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers) Green, illustrated and written by Laura Vaccaro Seeger (Neal Porter Books, an imprint of Roaring Brook Press) One Cool Friend, illustrated by David Small, written by Toni Buzzeo (Dial Books for Young Readers, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group) Sleep Like a Tiger, illustrated by Pamela Zagarenski, written by Mary Logue (Houghton Mifflin Books for Children, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company) 2012 Medal Winner: A Ball for Daisy by Chris Raschka (Schwartz & Wade Books, an imprint of Random House Children's Books, a division of Random House, Inc.) 2013 Honor Books: Blackout by John Rocco (Disney · Hyperion Books, an imprint of Disney Book Group) Grandpa Green by Lane Smith (Roaring Brook Press, a division of Holtzbrinck Publishing Holdings Limited Partnership) Me...Jane by Patrick McDonnell (Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.) 2011 Medal Winner: A Sick Day for Amos McGee, illustrated by Erin E. -

Science Magazine Podcast Transcript, 17 May 2013

Science Magazine Podcast Transcript, 17 May 2013 http://podcasts.aaas.org/science_news/SciencePodcast_130517_ScienceNOW.mp3 Promo The following is an excerpt from the Science Podcast. To hear the whole show, visit www.sciencemag.org and click on “Science Podcast.” Music Interviewer – Sarah Crespi Finally today, I’m here with David Grimm, online news editor for Science. He’s here to give us a rundown of some of the recent stories from our daily news site. I’m Sarah Crespi. So Dave, first up we have “dam” deforestation. Interviewee – David Grimm Sarah, this story is about hydropower. This is a major source of power in the world; turbines hooked up to dams, the water flows down, spins the turbine, and can power a lot. In fact, there is a dam that’s being constructed in Brazil called the Belo Monte Dam, which is a 14 billion dollar project. And when it’s complete, it will have the third greatest capacity for generating hydropower in the world. Interviewer – Sarah Crespi Okay, so what about the trees? Interviewee – David Grimm Well, there’s a problem: to build these dams you’ve got to cut down a lot of trees, and that has its own ecological problems. But engineers didn’t worry about the cutting down the trees themselves as a problem for the dam power; in fact, they thought that cutting down the trees would actually improve hydroelectric power, the reason being that trees suck up a lot of water from the soil. It’s a process known as evapotranspiration, where the water gets sucked up into the trees, the trees transpire the water through their leaves, and that water enters the atmosphere. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme

Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy Volume 6 Article 4 1-1-1998 Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme Kimberly J. Pierson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/circles Part of the Law Commons, and the Legal Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pierson, Kimberly J. (1998) "Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme," Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy: Vol. 6 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/circles/vol6/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIRCLES 1998 Vol. VI REVENGE AND PUNISHMENT: LEGAL PROTOTYPE AND FAIRY TALE THEME By Kimberly J. Pierson' The study of the interrelationship between law and literature is currently very much in vogue, yet many aspects of it are still relatively unexamined. While a few select works are discussed time and time again, general children's literature, a formative part of a child's emerging notion of justice, has been only rarely considered, and the traditional fairy tale2 sadly ignored. This lack of attention to the first examples of literature to which most people are exposed has had a limiting effect on the development of a cohesive study of law and literature, for, as Ian Ward states: It is its inter-disciplinary nature which makes children's literature a particularly appropriate subject for law and literature study, and it is the affective importance of children's literature which surely elevates the subject fiom the desirable to the necessary. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Restoration of Heterogeneous Disturbance Regimes for the Preservation of Endangered Species Steven D

RESEARCH ARTICLE Restoration of Heterogeneous Disturbance Regimes for the Preservation of Endangered Species Steven D. Warren and Reiner Büttner ABSTRACT Disturbance is a natural component of ecosystems. All species, including threatened and endangered species, evolved in the presence of, and are adapted to natural disturbance regimes that vary in the kind, frequency, severity, and duration of disturbance. We investigated the relationship between the level of visible soil disturbance and the density of four endan- gered plant species on U.S. Army training lands in the German state of Bavaria. Two species, gray hairgrass (Corynephorus canescens) and mudwort (Limosella aquatica), showed marked affinity for or dependency on high levels of recent soil disturbance. The density of fringed gentian (Gentianella ciliata) and shepherd’s cress (Teesdalia nudicaulis) declined with recent disturbance, but appeared to favor older disturbance which could not be quantified by the methods employed in this study. The study illustrates the need to restore and maintain disturbance regimes that are heterogeneous in terms of the intensity of and time since disturbance. Such a restoration strategy has the potential to favor plant species along the entire spectrum of ecological succession, thereby maximizing plant biodiversity and ecosystem stability. Keywords: fringed gentian, gray hairgrass, heterogeneous disturbance hypothesis, mudwort, shepherd’s cress cosystems and the species that create and maintain conditions neces- When the European Commission Einhabit them typically evolve in sary for survival. issued Directive 92/43/EEC (Euro- the presence of quasi-stable distur- The grasslands of northern Europe pean Economic Community 1992) bance regimes which are characterized lie within what would be mostly forest requiring all European Union nations by general patterns of perturbation, in the absence of disturbance. -

CRY of the Nameless 130 August 1959

CRY of the Nameless 130 August 1959 T CARR TAFF (Over my dead body.........BRT) This is indeed. Gry, the Precarious Monthly Fanzine. We have here issue 7/130, dated August, 1959- In deference to its predecessors, issue #130 claims residence at Box 92,. 920-3rd Ave, Seattle 4? Wash. Cry is sometimes obtained for 250 (5/$l, 12/02). Sterling characters in the UK may send moneys (1/9 per copy, 5 for 7/-, or 12 for 14/-) to John Berry, 31 Campbell park Ave, Belmont, Belfast, Northern Ireland. However, it should be mentioned that Mr Berry will be away from home for a few weeks- toward the latter part of August and for a goodly portion of September (like, hoo-HAE) so patience is urged upon our sterling subbers during that period. Cry also goes to contributors, upon publication. This includes writers of letters that are printed, * or which miss publication due to lack of space rather than lack of interest, as adjudged by Elinor. Up to and including this issue, editors of zines reviewed in Cry also receive a copy of the issue containing the review. Read on; we also have The Contents (in new, Quick-Drying Black i Cover by Don Franson; Liultigraphy by Toskey page 1 All this, and the Editorial, too F H Busby 3 The Science-Fiction Field Plowed Under Renfrew Pemberton 4 Fandom Harvest Terry Carr 8 I Was A Fakefan For The FBI John Berry 10 CRYing Over Bent Staples Rich Brown & Bob Lichtman 1-4 "CrudCon I: 0 What Fun!" Es Adams 16 Charlie Phan at the Detention Les Nirenberg 18 Little Eustace's After-School Hour Terry Carr 20 High CRYteria Leslie Gerber 23 MINUTES Wally Weber 24 CRY of the Readers conducted by Elinor Busby 26 (If this Q-D Black reduces offset as promised, we stay Black except for specials.,. -

1 September 8, 2014 Todd K. Grimm, State Director Idaho Wildlife Services

September 8, 2014 Todd K. Grimm, State Director Idaho Wildlife Services (“WS”) 9134 West Blackeagle Dr. Boise, ID 83709 [email protected] VIA EMAIL AND CERTIFIED MAIL Re: Idaho Wildlife Services compliance with NEPA, ESA Dear Mr. Grimm: In accordance with the 60-day notice requirement of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. § 1540(g), Western Watersheds Project, WildEarth Guardians, the Center for Biological Diversity, and Friends of the Clearwater hereby provide notice of intent to sue for violations of the ESA relating to Idaho Wildlife Service’s ongoing operations and programs, as well as violations of compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act (“NEPA”). NEPA ISSUES The U.S. Department of Agriculture-Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service- Wildlife Services (“WS”) issued a Central and Northern Idaho Predator Control Environmental Assessment (“EA”) in 1996, along with a subsequent finding of no significant impact (“FONSI”) in 2004. It issued an EA and FONSI for Predator Damage Management in Southern Idaho in 2002, with a “five year update” in 2007 and another FONSI in 2008. A subsequent EA and FONSI issued in 2011 concerned Idaho wolf management only. After examining these documents, it is apparent that WS’s operations in Idaho have been and are being conducted with either no or inadequate compliance with NEPA. Because Idaho WS’s EAs tier to the outdated 1994/1997 Animal Damage Control Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (“PEIS”), and because much of the literature upon which WS relies is outdated or uninformed by the best available science, we request that WS conduct a new environmental analysis – either new EAs or a cumulative environmental impact statement (“EIS”) for the State of Idaho, and that in the meantime it cease and desist all operations until adequate analyses are undertaken. -

On the Passions of Kings: Tragic Transgressors of the Sovereign's

ON THE PASSIONS OF KINGS: TRAGIC TRANSGRESSORS OF THE SOVEREIGN’S DOUBLE BODY IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY FRENCH THEATRE by POLLY THOMPSON MANGERSON (Under the Direction of Francis B. Assaf) ABSTRACT This dissertation seeks to examine the importance of the concept of sovereignty in seventeenth-century Baroque and Classical theatre through an analysis of six representations of the “passionate king” in the tragedies of Théophile de Viau, Tristan L’Hermite, Pierre Corneille, and Jean Racine. The literary analyses are preceded by critical summaries of four theoretical texts from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in order to establish a politically relevant definition of sovereignty during the French absolutist monarchy. These treatises imply that a king possesses a double body: physical and political. The physical body is mortal, imperfect, and subject to passions, whereas the political body is synonymous with the law and thus cannot die. In order to reign as a true sovereign, an absolute monarch must reject the passions of his physical body and act in accordance with his political body. The theory of the sovereign’s double body provides the foundation for the subsequent literary study of tragic drama, and specifically of king-characters who fail to fulfill their responsibilities as sovereigns by submitting to their human passions. This juxtaposition of political theory with dramatic literature demonstrates how the king-character’s transgressions against his political body contribute to the tragic aspect of the plays, and thereby to the -

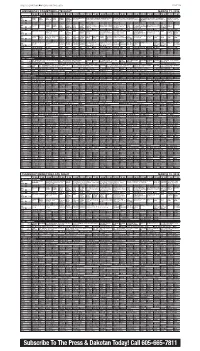

Subscribe to the Press & Dakotan Today!

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, MARCH 6, 2015 PAGE 9B WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT MARCH 11, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Odd Wild Cyber- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You 50 Years With Peter, Paul and Mary Perfor- John Sebastian Presents: Folk Rewind NOVA The tornado PBS (DVS) Squad Kratts Å chase Speaks Business Stereo) Å Finding financial solutions. (In Stereo) Å mances by Peter, Paul and Mary. (In Stereo) Å (My Music) Artists of the 1950s and ’60s. (In outbreak of 2011. (In KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å Stereo) Å KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent Myst-Laura Law & Order: SVU Chicago PD News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Mysteries of Law & Order: Special Chicago PD Two teen- KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Laura A star athlete is Victims Unit Å (DVS) age girls disappear. News Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (In Stereo) Å With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory killed. Å Å (DVS) (N) Å (In Stereo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

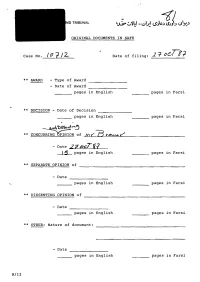

Page 1 MS TRIBUNAL ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS in SAFE Case No

MS TRIBUNAL ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS IN SAFE Case No. / CJ f / 2.. Date of filing: ). '=1- oe,,,,Tf:; ** AWARD - Type of Award -------- - Date of Award ----------- ---- pages in English ---- pages in Farsi "'' ** DECISION - Date of Decision pages in English pages in Farsi .. "'~ ~\S5c n·b~ ** CONCU~Nof M < ]3 r ~ v - Date 2 7 e,tt:,/ 'i ·2 15 pages in English pages in Farsi ** SEPARATE OPINION of - Date 'lo,, pages in English pages in Farsi ** DISSENTING OPINION of - Date pages in English pages in Farsi ** OTHER1 Nature of document: - Date --- pages in English ---- pages in Farsi R/12 .. !RAN-UNITED ST ATES CLAIMS TRIBUNAL ~ ~~\,\- - \:J\r\- l>J~.> c.S.J.,,.> ~~.) CASE NO.10712 CHAMBER THREE AWARD NO.321-10712-3 IUH UNITEO lffATIII J,1. • ..r;.11 J .!! JI• &AIMS TRIBUNAi: a...,_.:,'i~l__,~I HARRINGTON AND ASSOCIATES, INC., a: - ... a claim of less than U.S.$250,000 FILED • ~.l--•I ~ presented by the ... 2 7 0 CT 1987 c-.-1: UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, 1iff /A/ a Claimant, and 10 7 1 2 THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN, Respondent. CONCURRING AND DISSENTING OPINION OF JUDGE BROWER 1. This Award regrettably perpetuates the schizophrenia which from the Tribunal's inception has characterized its approach towards the belated specification of parties. 2. The first episode was the Tribunal's action in accept ing for filing a claim lodged against Iranian respondents by "AMF Overseas Corporation (Swiss Company) (wholly owned subsidiary of AMF Inc.)," notwithstanding the complete absence of any allegation in the Statement of Claim regard- ing the nationality -

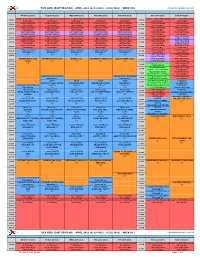

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO