A Case Study of Editorial Filters in Folktales: a Discussion of the Allerleirauh Tales in Grimm*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queering Kinship in 'The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers'

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 2012 Queering Kinship in ‘The aideM n Who Seeks Her Brothers' Jeana Jorgensen Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Folklore Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jorgensen, Jeana, "Queering Kinship in ‘The aideM n Who Seeks Her Brothers'" Transgressive Tales: Queering the Brothers Grimm / (2012): 69-89. Available at http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers/698 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 3 Queeting KinJtlip in ''Ttle Maiden Wtlo See~J Het BtottletJ_,_, JEANA JORGENSEN Fantasy is not the opposite of reality; it is what reality forecloses, and, as a result, it defines the limits of reality, constituting it as its constitutive outside. The critical promise of fantasy, when and where it exists, is to challenge the contingent limits of >vhat >vill and will not be called reality. Fa ntasy is what allows us to imagine ourselves and others otherwise; it establishes the possible in excess of the real; it points elsewhere, and when it is embodied, it brings the elsewhere home. -Judith Butler, Undoing Gender The fairy tales in the Kinder- und Hausmiirchen, or Children's and Household Tales, compiled by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm are among the world's most popular, yet they have also provoked discussion and debate regarding their authenticity, violent imagery, and restrictive gender roles. -

Introduction: Fairy Tale Films, Old Tales with a New Spin

Notes Introduction: Fairy Tale Films, Old Tales with a New Spin 1. In terms of terminology, ‘folk tales’ are the orally distributed narratives disseminated in ‘premodern’ times, and ‘fairy tales’ their literary equiva- lent, which often utilise related themes, albeit frequently altered. The term ‘ wonder tale’ was favoured by Vladimir Propp and used to encompass both forms. The general absence of any fairies has created something of a mis- nomer yet ‘fairy tale’ is so commonly used it is unlikely to be replaced. An element of magic is often involved, although not guaranteed, particularly in many cinematic treatments, as we shall see. 2. Each show explores fairy tale features from a contemporary perspective. In Grimm a modern-day detective attempts to solve crimes based on tales from the brothers Grimm (initially) while additionally exploring his mythical ancestry. Once Upon a Time follows another detective (a female bounty hunter in this case) who takes up residence in Storybrooke, a town populated with fairy tale characters and ruled by an evil Queen called Regina. The heroine seeks to reclaim her son from Regina and break the curse that prevents resi- dents realising who they truly are. Sleepy Hollow pushes the detective prem- ise to an absurd limit in resurrecting Ichabod Crane and having him work alongside a modern-day detective investigating cult activity in the area. (Its creators, Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman, made a name for themselves with Hercules – which treats mythical figures with similar irreverence – and also worked on Lost, which the series references). Beauty and the Beast is based on another cult series (Ron Koslow’s 1980s CBS series of the same name) in which a male/female duo work together to solve crimes, combining procedural fea- tures with mythical elements. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

And the Fairy Tales Stephen Spitalny

experience with children’s play and are in a unique of WECAN from 1983-2001, and is the previous editor experience to share their insights—in workshops and of this newsletter. courses, in the classroom with visitors observing, in play days organized for community children, in articles for local papers and magazines. It is vital that play remain a central part of childhood. It contributes to all aspects of children’s development—physical, social, emotional and cognitive. Also, there are physical and mental illnesses that result when play disappears, and they can be serious in nature. For the sake of the children today, their future and that of our society we need to do all we can to protect play and restore it. Endnotes: 1 From Education as a Force for Social Change, August 9, 1919, pg. 11. Quoted in On the Play of the Child, WECAN (Spring Valley, 2004) pg 10. 2 From Roots of Education, April 16, 1924, pg. 60. Quoted in On the Play of the Child, WECAN (Spring Valley, 2004) pg 11. Joan Almon is a co-founder and the U.S. Coordinator of the Alliance for Childhood. She is the Co-General Secretary of the Anthroposophical Society in America. Joan taught kindergarten for many years at Acorn Hill in Maryland. She was the co-founder and chairperson The Name of “John” and the Fairy Tales Stephen Spitalny This is the second in a series of article looking inner tendencies; it needs the wonderful soul- into the depths of fairy tales and trying to shed nourishment it finds in fairy tale pictures, for light on some of what can be found within. -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

TEACHER RESOURCE PACK for Teachers Working with Pupils in Years 4 - 6 PHILIP PULLMAN’S GRIMM TALES

PHILIP PUllMAn’S gRiMM TAlES TEACHER RESOURCE PACK FOR teachers wORKing wiTH pupilS in YEARS 4 - 6 PHILIP PUllMAn’S gRiMM TAlES Adapted for the stage by Philip Wilson Directed by Kirsty Housley from 13 nOv 2018 - 6 jAn 2019 FOR PUPILS IN SCHOOl years 4 - 6 OnCE upon A christmas... A most delicious selection of Philip Pullman’s favourite fairytales by the Brothers Grimm, re-told and re-worked for this Christmas. Enter a world of powerful witches, enchanted forest creatures, careless parents and fearless children as they embark on adventures full of magic, gore, friendship, and bravery. But beware, these gleefully dark and much-loved tales won’t be quite what you expect… Duration: Approx 2 hrs 10 mins (incl. interval) Grimm Tales For Young and Old Copyright © 2012, Phillip Pullman. All rights reserved. First published by Penguin Classics in 2012. Page 2 TEACHER RESOURCES COnTEnTS introdUCTiOn TO the pack p. 4 AbOUT the Play p. 6 MAKing the Play: interviEw wiTH director Kirsty HOUSlEY p. 8 dRAMA activiTiES - OverviEw p. 11 SEQUEnCE OnE - “OnCE UPOn A TiME” TO “HAPPILY EvER AFTER” p. 12 sequenCE TwO - the bEginning OF the story p. 15 sequenCE THREE - RAPUnZEl STORY wHOOSH p. 22 sequenCE FOUR - RAPUnZEl’S dREAM p. 24 sequenCE FivE - THE WITCH’S PROMiSES: wRiTING IN ROlE p. 26 RESOURCES FOR ACTiviTiES p. 29 Page 3 TEACHER RESOURCES INTROdUCTiOn This is the primary school pack for the Unicorn’s production of Philip Pullman’s Grimm Tales in Autumn 2018. The Unicorn production is an adaptation by Philip Wilson of Philip Pullman’s retelling of the classic fairytales collected in 19th century Germany by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. -

KIN S FUR.Indd

allerleirauh cinderella ALL KINDS OF FUR Erasure Poems & New Translation of a tale from the Brothers Grimm Margaret Yocom deerbrook editions published by Deerbrook Editions P.O. Box 542 Cumberland, ME 04021 www.deerbrookeditions.com first edition © 2018 by Margaret Yocom All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-9991062-5-9 Author photograph by Jamie Lynn Photography. Cover art: Bear Girl by Anne Siems. www.annesiems.com Book Design by Jeffrey Haste. For John A note on the text: Poems in black font are erasures of the Author’s translation of Jakob and Wilhelm Grimms’ 1857 tale “Allerleirauh” (“All Kinds Of Fur”), a version of “Cinderella” that opens with incest. Contents Once there was a king 1 O golden hair and ashes 2 For a long time, the king could not 3 For a long time, I could not 4 Now the king had a daughter 5 daughter mother such golden hair 6 Then he spoke to his councillors 7 I a daughter a dead wife 8 The daughter was even more frightened 9 T he night herder’s maw 10 But she thought 11 turn 12 The king did not give up 13 his dun deer nears 14 Finally 15 all is red 16 In the night 17 go go 18 She walked the entire night 19 walk nigh hecate 20 Now it just so happened 21 so begin 22 When the hunters touched 23 touch 24 There 25 here 26 T hen 27 wood fire ashes 28 Now, one day 29 one so castled 30 to sweep up 31 the ashes tell 32 Everyone stepped aside 33 one step one 34 He thought in his heart 35 His eyes never behold 36 She, however 37 Swiftly Kind Fur 38 Now, when she came into the kitchen 39 Now, resume 40 And when the soup was ready -

Working Title

Three Drops of Blood: Fairy Tales and Their Significance for Constructed Families Carol Ann Lefevre Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Creative Writing Discipline of English School of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide South Australia June 2009 Contents 1. Abstract.……………………………………………………………iii 2. Statement of Originality…………………………………………..v 3. Introduction………………………………………………………...1 4. Identity and Maternal Blood in “The Goose Girl”………………9 5 “Cinderella”: The Parented Orphan and the ‘Motherline’….....19 6. Abandonment, Exploitation and the Unconscious Woman in “Sleeping Beauty”………………………………………….30 7. The Adoptive Mother and Maternal Gaze in “Little Snow White”………………………………………..44 8. “Rapunzel”: The Adoptee as Captive and Commodity………..56 9. Adoption and Difference in “The Ugly Duckling”……………..65 10. Conclusion……………………………………………………...…71 11. Appendix – The Child in the Red Coat: Notes on an Intuitive Writing Process………………………………....76 12. Bibliography................................................……………………...86 13. List of Images in the Text…..……………………………………89 ii Abstract In an outback town, Esther Hayes looks out of a schoolhouse window and sees three children struck by lightning; one of them is her son, Michael. Silenced by grief, Esther leaves her young daughter, Aurora, to fend for herself; against a backdrop of an absent father and maternal neglect, the child takes comfort wherever she can, but the fierce attachments she forms never seem to last until, as an adult, she travels to her father’s native Ireland. If You Were Mine employs elements of well-known fairy tales and explores themes of maternal abandonment and loss, as well as the consequences of adoption, in a narrative that laments the perilous nature of children’s lives. -

Fairytales in the German Tradition

German/LACS 233: Fairytales in the German Tradition Tuesday/Thursday 1:30-2:45 Seabury Hall S205 Julia Goesser Assaiante Seabury Hall 102 860-297-4221 Office Hours: Tuesday/Thursday 9-11, or by appointment Course description: Welcome! In this seminar we will be investigating fairytales, their popular mythos and their longevity across various cultural and historical spectrums. At the end of the semester you will have command over the origins of many popular fairytales and be able to discuss them critically in regard to their role in our society today. Our work this semester will be inter-disciplinary, with literary, sociological- historical, psychoanalytic, folklorist, structuralist and feminist approaches informing our encounter with fairytales. While we will focus primarily on the German fairytale tradition, in particular, the fairytales collected by the Brothers Grimm, we will also read fairytales from other cultural and historical contexts, including contemporary North America. Course requirements and grading: in order to receive a passing grade in this course you must have regular class attendance, regular and thoughtful class participation, and turn in all assignments on time. This is a seminar, not a lecture-course, which means that we will all be working together on the material. There will be a total of three unannounced (but open note) quizzes throughout the semester, one in-class midterm exam, two five-page essays and one eight-page final essay assignment. With these essays I hope to gauge your critical engagement with the material, as well as helping you hone your critical writing skills. Your final grade breaks down as follows: Quizzes 15% Midterm 15% 2- 5 page essays (15% each) 30% 1 8 page essay 20% Participation 20% House Rules: ~Class attendance is mandatory. -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

Fairy Tales Then and Now(Syllabus 2019)

Spring 2019 Professor Martha Helfer Office: AB 4125 Office hours, MW 1:30-2:30 p.m. and by appointment [email protected] Fairy Tales Then and Now MW5, 2:50-4:10 pm, AB 2225 01:470:225:01 (index 10423) 01: 470: 225: 02 (index 13663) 01:470:225:03 (index 18813) 01:470:225:04 (index 21452) 01: 470: H1 (index 13662) 01:195:246:01 (index 10485) 1 Course description: This course analyzes the structure, meaning, and function of fairy tales and their enduring influence on literature and popular culture. While we will concentrate on the German context, and in particular the works of the Brothers Grimm, we also will consider fairy tales drawn from a number of different national traditions and historical periods, including the American present. Various strategies for interpreting fairy tales will be examined, including methodologies derived from structuralism, folklore studies, gender studies, and psychoanalysis. We will explore pedagogical and political uses and abuses of fairy tales. We will investigate the evolution of specific tale types and trace their transformations in various media from oral storytelling through print to film, television, and the stage. Finally, we will consider potential strategies for the reinterpretation and rewriting of fairy tales. This course has no prerequisites. Core certification: Satisfies SAS Core Curriculum Requirements AHp, WCd Arts and Humanities Goal p: Student is able to analyze arts and/or literature in themselves and in relation to specific histories, values, languages, cultures, and/or technologies. Writing and Communication Goal d: Student is able to communicate effectively in modes appropriate to a discipline or area of inquiry. -

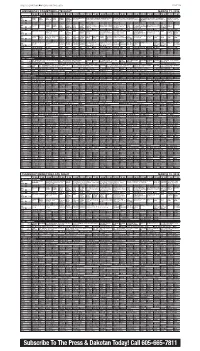

Subscribe to the Press & Dakotan Today!

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, MARCH 6, 2015 PAGE 9B WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT MARCH 11, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Odd Wild Cyber- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You 50 Years With Peter, Paul and Mary Perfor- John Sebastian Presents: Folk Rewind NOVA The tornado PBS (DVS) Squad Kratts Å chase Speaks Business Stereo) Å Finding financial solutions. (In Stereo) Å mances by Peter, Paul and Mary. (In Stereo) Å (My Music) Artists of the 1950s and ’60s. (In outbreak of 2011. (In KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å Stereo) Å KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent Myst-Laura Law & Order: SVU Chicago PD News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Mysteries of Law & Order: Special Chicago PD Two teen- KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Laura A star athlete is Victims Unit Å (DVS) age girls disappear. News Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (In Stereo) Å With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory killed. Å Å (DVS) (N) Å (In Stereo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr.