Certiorari Petition, See 137 S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

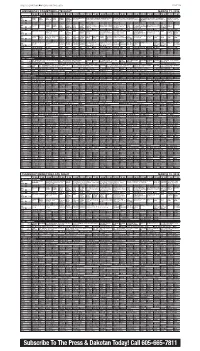

Subscribe to the Press & Dakotan Today!

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, MARCH 6, 2015 PAGE 9B WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT MARCH 11, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Odd Wild Cyber- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You 50 Years With Peter, Paul and Mary Perfor- John Sebastian Presents: Folk Rewind NOVA The tornado PBS (DVS) Squad Kratts Å chase Speaks Business Stereo) Å Finding financial solutions. (In Stereo) Å mances by Peter, Paul and Mary. (In Stereo) Å (My Music) Artists of the 1950s and ’60s. (In outbreak of 2011. (In KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å Stereo) Å KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent Myst-Laura Law & Order: SVU Chicago PD News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Mysteries of Law & Order: Special Chicago PD Two teen- KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Laura A star athlete is Victims Unit Å (DVS) age girls disappear. News Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (In Stereo) Å With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory killed. Å Å (DVS) (N) Å (In Stereo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

495 the Honorable Paul W. Grimm* & David

A PRAGMATIC APPROACH TO DISCOVERY REFORM: HOW SMALL CHANGES CAN MAKE A BIG DIFFERENCE IN CIVIL DISCOVERY The Honorable Paul W. Grimm & David S. Yellin I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 495 II. INSTITUTIONAL PROBLEMS IN CIVIL PRACTICE .......................................... 501 A. The Vanishing Jury Trial ..................................................................... 501 B. A Lack of Active Judicial Involvement ................................................. 505 C. The Changing Nature of Discovery ..................................................... 507 1. The Growth of Discovery Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ...................................................................................... 508 2. The Expansion in Litigation .......................................................... 510 3. The Advent of E-Discovery ........................................................... 511 III. PROPOSED REFORMS TO CIVIL DISCOVERY ................................................ 513 A. No. 1. Excessively Broad Scope of Discovery ...................................... 514 B. No. 2. Producing Party Pays vs. Requesting Party Pays ..................... 520 C. No. 3. The Duty to Cooperate During Discovery ................................ 524 IV. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................... 533 I. INTRODUCTION In 2009, the American Bar Association (ABA) Section of Litigation conducted a survey -

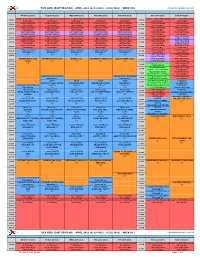

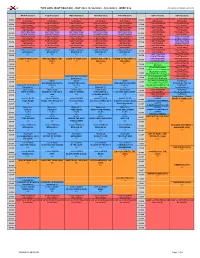

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

A Case Study of Editorial Filters in Folktales: a Discussion of the Allerleirauh Tales in Grimm*

A castle. From German edition of the Grimm Tales c. 1890. Illustrations by Philip Grot Johann and R. Leinweber A CASE STUDY OF EDITORIAL FILTERS IN FOLKTALES: A DISCUSSION OF THE ALLERLEIRAUH TALES IN GRIMM* Cay Dollerup, Iven Reventlow, Carsten Rosenberg Hansen, Denmark In the article on the ontological article of folktales which listed as no. 73 on this homepage, we ar- gued that discussions of folktales would have a sound basis if we posited an ‘ideal tale’ which briefly ex- ists in a unique ‘continuum’. In this continuum, ‘there is a narrative contract between a narrator and an audience at a specific place in space and time and in an oral dimension with a dynamic social interplay’ 1. We also argued that once a tale is recorded, ‘filters’ begin to make their impact and that this must be taken into account. In the present article, we shall discuss editorial ‘filters; specifically the changes, ‘orientations; which editors deliberately impose on a tale because they want to reach a specific audience. Our case in point will be the tale called Allerleirauh in the collection published by the German scholars, the brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (1812-1815). The tale is found in an incomplete version in the earliest papers preserved from the brothers collec- tion activities, and this probably explains why it has not been studied in depth before: but as we hope to show, it is not only highly illustrative of editorial filters, but it may also contribute to a better under- standing of the brothers Grimm and their methods of collecting tales. -

A-Field-Guide-To-Demons-By-Carol-K

A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS CAROL K. MACK AND DINAH MACK AN OWL BOOK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK Owl Books Henry Holt and Company, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10010 www.henryholt.com An Owl Book® and ® are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Copyright © 1998 by Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack All rights reserved. Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd. Library of Congress-in-Publication Data Mack, Carol K. A field guide to demons, fairies, fallen angels, and other subversive spirits / Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack—1st Owl books ed. p. cm. "An Owl book." Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-6270-0 ISBN-10: 0-8050-6270-X 1. Demonology. 2. Fairies. I. Mack, Dinah. II. Title. BF1531.M26 1998 99-20481 133.4'2—dc21 CIP Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets. First published in hardcover in 1998 by Arcade Publishing, Inc., New York First Owl Books Edition 1999 Designed by Sean McDonald Printed in the United States of America 13 15 17 18 16 14 This book is dedicated to Eliza, may she always be surrounded by love, joy and compassion, the demon vanquishers. Willingly I too say, Hail! to the unknown awful powers which transcend the ken of the understanding. And the attraction which this topic has had for me and which induces me to unfold its parts before you is precisely because I think the numberless forms in which this superstition has reappeared in every time and in every people indicates the inextinguish- ableness of wonder in man; betrays his conviction that behind all your explanations is a vast and potent and living Nature, inexhaustible and sublime, which you cannot explain. -

Lieutenant Colonel Michael C. Grimm 18 February 1947 - 7 October 1981

Lieutenant Colonel Michael C. Grimm 18 February 1947 - 7 October 1981 Mike has been described by the pilots and friends who knew him as a hard charger, a dynamo, a great pilot, and a natural leader. With a youthful face, a quick wit and a steady hand, this fine pilot was snatched from our fold at the very inception of the 160th’s existence. Who was this man, this legend from our Night Stalker past? Lieutenant Colonel Michael C. Grimm came to Task Force 160 with a stellar background. He volunteered for service in the U.S. Army at age 19 and graduated from Infantry Basic in March 1967. He was sent to Vietnam where he firmly established his unquestionable courage and dedication to duty. For his gallantry in action in Vietnam, LTC Grimm was awarded the nation’s second highest award, the Distinguished Service Cross. He was a warrior and a hero. He returned home to several command positions, but was searching for another challenge and found it flying. LTC Grimm went to flight school, and was sent back to Vietnam in May of 1971 as a pilot with C Troop, 2/17 CAV. He flew combat missions in Vietnam, and returned home with the Purple Heart, Air Medals, and a Bronze Star (w/”V” Device). In 1975, LTC Grimm was sent to Hawaii where he first served as the Executive Officer of an Aviation Company and then took command in November 1975. Command was not the only thing waiting for him in that tropical paradise. He met his lovely wife, Karen, and they returned stateside together in 1978. -

High Flyer Lockheed Martin Moving F-16 Jet Production to S.C

IN SPORTS: Defending champ LMA softball returns plenty of experience for another title run B1 SCIENCE Arctic sea ice records new low for winter A6 FRIDAY, MARCH 24, 2017 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents Combating prison cellphones in prison, which corrections missioners how he was shot Ex-corrections directors across the country six times at his home early say is what they need to shut one morning in March 2010. down inmate cellphone use, “My doctor said I should be officer testifies once and for all. dead. ... Last Wednesday, I had But commissioners includ- surgery Number 24, but who’s in front of FCC ing Chairman Ajit Pai said the counting?” step was one that could hope- At the time, Johnson was COLUMBIA (AP) — Federal fully begin to combat the the lead officer tasked with officials took a step Thursday phones that officials say are keeping contraband items like toward increasing safety in the No. 1 safety issue behind tobacco, weapons and cell- prisons by making it easier to bars. phones out of Lee Correction- find and seize cellphones ob- The vote came after power- al Institution, a prison 50 tained illegally by inmates, ful testimony from Robert miles east of Columbia that voting unanimously to ap- Johnson, a former South Car- houses some of the state’s prove rules to streamline the olina corrections officer who most dangerous criminals. process for using technology was nearly killed in a shoot- The items are smuggled in- AP FILE PHOTO to detect and block contra- ing that authorities said was side, tossed over fences or Capt. -

Kinsella Feb 13

MORPHEUS: A BILDUNGSROMAN A PARTIALLY BACK-ENGINEERED AND RECONSTRUCTED NOVEL MORPHEUS: A BILDUNGSROMAN A PARTIALLY BACK-ENGINEERED AND RECONSTRUCTED NOVEL JOHN KINSELLA B L A Z E V O X [ B O O K S ] Buffalo, New York Morpheus: a Bildungsroman by John Kinsella Copyright © 2013 Published by BlazeVOX [books] All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the publisher’s written permission, except for brief quotations in reviews. Printed in the United States of America Interior design and typesetting by Geoffrey Gatza First Edition ISBN: 978-1-60964-125-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012950114 BlazeVOX [books] 131 Euclid Ave Kenmore, NY 14217 [email protected] publisher of weird little books BlazeVOX [ books ] blazevox.org 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 B l a z e V O X trip, trip to a dream dragon hide your wings in a ghost tower sails crackling at ev’ry plate we break cracked by scattered needles from Syd Barrett’s “Octopus” Table of Contents Introduction: Forging the Unimaginable: The Paradoxes of Morpheus by Nicholas Birns ........................................................ 11 Author’s Preface to Morpheus: a Bildungsroman ...................................................... 19 Pre-Paradigm .................................................................................................. 27 from Metamorphosis Book XI (lines 592-676); Ovid ......................................... 31 Building, Night ...................................................................................................... -

The Mississippi Pilot

:;-"!!•-, • ";-'?' •": i^HlglS I ^'. "'W^::''%'^: •iiiBiiiliiii Z:S-' i>. "-i •AA kV\ ^H LONDON! WARD. LOCK. AND CO. Sold LjrallC]iemi7ts|ious" p^ifylng properties of pure Vegetable Charcoal upon the Human System have only recently been recog nised. It ab sorbs all acidity and impure gases in the Stomach and Bowels, and thus gives a healthy tone to the digestive organs. WHELPTON'S VEGETABLE PURIFYING PILLS . — • During a period of more than FORTY-SIX YEARS they have I TRADE wflRKUEcisTEREDjj been us'^d Hiost cxtcnsively as a FAMILY MEDICINE, thou sands having found them a simple and safe remedy, and one needful to be kept always at hand. These Pills are purely Vegetable, being entirely free from Mercury or any other Mineral, and those who may not hitherto have proved their efficacy, will do well to give them a trial. Recommended for Di.<;orders of the HEAD, CHEST, BOWELS, LIVER, and KIDNEYS ; also in RHEUMATISM, ULCERS, SORES, and all SKIN DISEASES—these Pills being a direct Purifier of the Blood. In Boxes, price ^\d., IS. iK> and 2s. gd., by Or. "WHELPTOK" & SOZST. 3, Crane Court, Fleet Street, London, and sent free to any part of the United Kingdom on receipt of 8, 14, or 33 Stamps. Sold by all Chemists^ at Home ajid A broad, ROWLANDS' ODONTO Is the purest and most fragrant Dentifrice ever made ; it whitens the Teeth, prevents decay, and gives a pleasing fragrance to the Breath ; and the fact of its containing no acid or mineral ingredients specially adapts it for the Teeth of Children. -

MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM MON (4/26/2021) TUE (4/27/2021) WED (4/28/2021) THU (4/29/2021) FRI (4/30/2021) SAT (5/1/2021) SUN (5/2/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract