The Return of the Repressed: Gothic Horror from T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gone Girl : a Novel / Gillian Flynn

ALSO BY GILLIAN FLYNN Dark Places Sharp Objects This author is available for select readings and lectures. To inquire about a possible appearance, please contact the Random House Speakers Bureau at [email protected] or (212) 572-2013. http://www.rhspeakers.com/ This book is a work of ction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used ctitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Copyright © 2012 by Gillian Flynn Excerpt from “Dark Places” copyright © 2009 by Gillian Flynn Excerpt from “Sharp Objects” copyright © 2006 by Gillian Flynn All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.crownpublishing.com CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Flynn, Gillian, 1971– Gone girl : a novel / Gillian Flynn. p. cm. 1. Husbands—Fiction. 2. Married people—Fiction. 3. Wives—Crimes against—Fiction. I. Title. PS3606.L935G66 2012 813’.6—dc23 2011041525 eISBN: 978-0-307-58838-8 JACKET DESIGN BY DARREN HAGGAR JACKET PHOTOGRAPH BY BERND OTT v3.1_r5 To Brett: light of my life, senior and Flynn: light of my life, junior Love is the world’s innite mutability; lies, hatred, murder even, are all knit up in it; it is the inevitable blossoming of its opposites, a magnicent rose smelling faintly of blood. -

Recepção Lusófona De Hermann Broch

1 Bonomo, D. - Recepção lusófona de Broch Recepção lusófona de Hermann Broch – Período 1959-2015 [Hermann Broch’s reception in Brazil and Portugal between 1959 and 2015] http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/1982-88371928119 Daniel Bonomo1 Abstract: The response, in Brazil and Portugal, to recently published editions of the novels The Sleepwalkers and The Death of Vergil by Hermann Broch shows a growing interest in, or perhaps a rather late response to, the author. One might wonder what events have been shaping the history of his literary presence in the Portuguese speaking world. This paper takes an unprecedented look at how Broch’s fictional and theoretical works have been received, in Portuguese, from the 1950s to the present day and provides a framework of main events – inclusions in the literary historiography, translations, theoretical and artistic utilizations. The objective is to expand the map of Broch’s readings and to offer references which might promote further discussions and advance the research on the author and his work. Keywords: German literature; Hermann Broch; Reception in Brazil and Portugal Resumo: Edições publicadas entre 2011 e 2014 no Brasil e em Portugal dos romances Os sonâmbulos e A morte de Virgílio, de Hermann Broch, mais que indícios de um interesse crescente ou uma acolhida tardia, incentivam pensar que episódios vêm compondo a história de sua presença em língua portuguesa. O artigo apresenta um levantamento inédito da recepção lusófona das obras ficcional e teórica de Hermann Broch desde o fim da década de 1950 até o presente e fornece um quadro se não conclusivo ao menos organizador dos principais momentos – inclusões na historiografia literária, traduções, aproveitamentos teóricos e artísticos – que dão forma a essa história apenas começada. -

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

Study/ Resource Guide

Georgia Milestones Assessment System Study/Resource Guide for Students and Parents American Literature and Composition Study/Resource Guide Study/Resource The Study/Resource Guides are intended to serve as a resource for parents and students. They contain practice questions and learning activities for the course. The standards identified in the Study/Resource Guides address a sampling of the state-mandated content standards. For the purposes of day-to-day classroom instruction, teachers should consult the wide array of resources that can be found at www.georgiastandards.org. Copyright © 2020 by Georgia Department of Education. All rights reserved. Table of Contents THE GEORGIA MILESTONES ASSESSMENT SYSTEM .................................... 3 GEORGIA MILESTONES END-OF-COURSE (EOC) ASSESSMENTS . 4 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE ........................................................ 5 OVERVIEW OF THE AMERICAN LITERATURE AND COMPOSITION EOC ASSESSMENT ........... 6 ITEM TYPES . 6 DEPTH OF KNOWLEDGE DESCRIPTORS . 7 DEPTH OF KNOWLEDGE EXAMPLE ITEMS . 10 DESCRIPTION OF TEST FORMAT AND ORGANIZATION . 21 PREPARING FOR THE AMERICAN LITERATURE AND COMPOSITION EOC ASSESSMENT ........ 22 STUDY SKILLS . 22 ORGANIZATION—OR TAKING CONTROL OF YOUR WORLD . 22 ACTIVE PARTICIPATION . 22 TEST-TAKING STRATEGIES . 22 PREPARING FOR THE AMERICAN LITERATURE AND COMPOSITION EOC ASSESSMENT . 23 CONTENT OF THE AMERICAN LITERATURE AND COMPOSITION EOC ASSESSMENT ........... 24 SNAPSHOT OF THE COURSE . 25 READING PASSAGES AND ITEMS . 26 UNIT 1: READING LITERARY TEXT . 27 UNIT 2: READING INFORMATIONAL TEXT . 41 UNIT 3: WRITING . 54 UNIT 4: LANGUAGE . 82 SAMPLE ITEMS ANSWER KEY . 93 SCORING RUBRICS AND EXEMPLAR RESPONSES . 102 WRITING RUBRICS . 109 APPENDIX: LANGUAGE PROGRESSIVE SKILLS, BY GRADE ............................. 116 Copyright © 2020 by Georgia Department of Education. All rights reserved. -

A Memoir and Writing Family Love: Autobiographical Novel to Memoir, an Exegesis

FAMILY LOVE: A MEMOIR AND WRITING FAMILY LOVE: AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NOVEL TO MEMOIR, AN EXEGESIS JUDY ROSEMARY SCOTT (ka Rosie) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for The degree of Doctor of Creative Arts In College of Arts School of Humanities and Languages UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY AUSTRALIA (2006) ABSTRACT When I first started thinking about writing Family Love I wanted to write it as an autobiographical novel. This meant a radical departure from my usual writing methods. For one thing, it was the first time in my writing life that I was interested in the conscious use of a period in my life as material for a novel. I had never before attempted this and felt a certain amount of apprehension in abandoning tried and true approaches for something so new and risky. The label, autobiographical novel, seemed to define most accurately for the purposes and process of the thesis what were in fact a series of decisions, vacillations and rationalisations. An autobiographical novel seemed the best form for what I wanted from Family Love, a book that combined the fictional momentum and surprises of a novel with the added depth of personal and political material consciously drawn from real life and living people. I believed that the detailed evocation of a specific time and place my childhood and early adolescence in Sandringham and Titirangi in New Zealand, aided by diaries and memory would allow the story to follow its own fictional bent, and to have the emotionally truthful resonance of fiction without necessarily being completely factual. Writing Family Love: Autobiographical novel to memoir 1 Introduction............................................................................................................2 2 Definition of an Autobiographical novel ................................................................12 3 The ‘Commentary’ ................................................................................................18 4. -

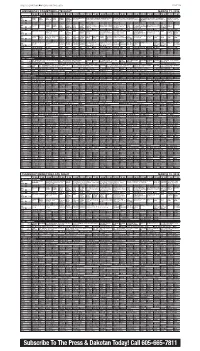

Subscribe to the Press & Dakotan Today!

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, MARCH 6, 2015 PAGE 9B WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT MARCH 11, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Odd Wild Cyber- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You 50 Years With Peter, Paul and Mary Perfor- John Sebastian Presents: Folk Rewind NOVA The tornado PBS (DVS) Squad Kratts Å chase Speaks Business Stereo) Å Finding financial solutions. (In Stereo) Å mances by Peter, Paul and Mary. (In Stereo) Å (My Music) Artists of the 1950s and ’60s. (In outbreak of 2011. (In KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å Stereo) Å KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent Myst-Laura Law & Order: SVU Chicago PD News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Mysteries of Law & Order: Special Chicago PD Two teen- KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Laura A star athlete is Victims Unit Å (DVS) age girls disappear. News Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (In Stereo) Å With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory killed. Å Å (DVS) (N) Å (In Stereo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

495 the Honorable Paul W. Grimm* & David

A PRAGMATIC APPROACH TO DISCOVERY REFORM: HOW SMALL CHANGES CAN MAKE A BIG DIFFERENCE IN CIVIL DISCOVERY The Honorable Paul W. Grimm & David S. Yellin I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 495 II. INSTITUTIONAL PROBLEMS IN CIVIL PRACTICE .......................................... 501 A. The Vanishing Jury Trial ..................................................................... 501 B. A Lack of Active Judicial Involvement ................................................. 505 C. The Changing Nature of Discovery ..................................................... 507 1. The Growth of Discovery Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ...................................................................................... 508 2. The Expansion in Litigation .......................................................... 510 3. The Advent of E-Discovery ........................................................... 511 III. PROPOSED REFORMS TO CIVIL DISCOVERY ................................................ 513 A. No. 1. Excessively Broad Scope of Discovery ...................................... 514 B. No. 2. Producing Party Pays vs. Requesting Party Pays ..................... 520 C. No. 3. The Duty to Cooperate During Discovery ................................ 524 IV. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................... 533 I. INTRODUCTION In 2009, the American Bar Association (ABA) Section of Litigation conducted a survey -

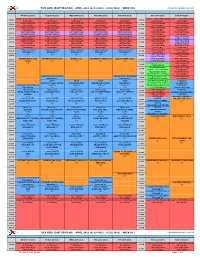

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

The Emergency Constitution

ACKERMAN40 3/5/2004 12:40 PM Essay The Emergency Constitution Bruce Ackerman† INTRODUCTION Terrorist attacks will be a recurring part of our future. The balance of technology has shifted, making it possible for a small band of zealots to wreak devastation where we least expect it—not on a plane next time, but with poison gas in the subway or a biotoxin in the water supply. The attack of September 11 is the prototype for many events that will litter the twenty- first century. We should be looking at it in a diagnostic spirit: What can we learn that will permit us to respond more intelligently the next time around? If the American reaction is any guide, we urgently require new constitutional concepts to deal with the protection of civil liberties. Otherwise, a downward cycle threatens: After each successful attack, politicians will come up with repressive laws and promise greater security—only to find that a different terrorist band manages to strike a few years later.1 This disaster, in turn, will create a demand for even more † Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science, Yale University. I presented earlier versions of this Essay at the Cardozo Conference on Emergency Powers and Constitutions and the Yale Global Constitutionalism Seminar. I am much indebted to the comments of Stephen Holmes and Carlos Rosenkrantz on the former occasion, and to a variety of constitutional court judges who participated in the latter event. Ian Ayres, Jack Balkin, Yochai Benkler, Paul Gewirtz, Dieter Grimm, Michael Levine, Daniel Markovits, Robert Post, Susan Rose-Ackerman, Jed Rubenfeld, and Kim Scheppele also provided probing critiques of previous drafts. -

Living Resources Report Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Results - Open Bay Habitat

Center for Coastal Studies CCBNEP Living Resources Report Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Results - Open Bay Habitat B. Living Resources - Habitats Detailed community profiles of estuarine habitats within the CCBNEP study area are not available. Therefore, in the following sections, the organisms, community structure, and ecosystem processes and functions of the major estuarine habitats (Open Bay, Oyster Reef, Hard Substrate, Seagrass Meadow, Coastal Marsh, Tidal Flat, Barrier Island, and Gulf Beach) within the CCBNEP study area are presented. The following major subjects will be addressed for each habitat: (1) Physical setting and processes; (2) Producers and Decomposers; (3) Consumers; (4) Community structure and zonation; and (5) Ecosystem processes. HABITAT 1: OPEN BAY Table Of Contents Page 1.1. Physical Setting & Processes ............................................................................ 45 1.1.1 Distribution within Project Area ......................................................... 45 1.1.2 Historical Development ....................................................................... 45 1.1.3 Physiography ...................................................................................... 45 1.1.4 Geology and Soils ................................................................................ 46 1.1.5 Hydrology and Chemistry ................................................................... 47 1.1.5.1 Tides .................................................................................... 47 1.1.5.2 Freshwater