Kinsella Feb 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jonathan Berger, an Introduction to Nameless Love

For Immediate Release Contact: [email protected], 646-492- 4076 Jonathan Berger, An Introduction to Nameless Love In collaboration with Mady Schutzman, Emily Anderson, Tina Beebe, Julian Bittiner, Matthew Brannon, Barbara Fahs Charles, Brother Arnold Hadd, Erica Heilman, Esther Kaplan, Margaret Morton, Richard Ogust, Maria A. Prado, Robert Staples, Michael Stipe, Mark Utter, Michael Wiener, and Sara Workneh February 23 – April 5, 2020 Opening Sunday, February 23, noon–7pm From February 23 – April 5, 2020, PARTICIPANT INC is pleased to present Jonathan Berger, An Introduction to Nameless Love, co-commissioned and co-organized with the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University. Taking the form of a large-scale sculptural installation that includes over 533,000 tin, nickel, and charcoal parts, Berger’s exhibition chronicles a series of remarkable relationships, creating a platform for complex stories about love to be told. The exhibition draws from Berger’s expansive practice, which comprises a spectrum of activity — brought together here for the first time — including experimental approaches to non-fiction, sculpture and installation, oral history and biography-based narratives, and exhibition-making practices. Inspired by a close friendship with fellow artist Ellen Cantor (1961-2013), An Introduction to Nameless Love charts a series of six extraordinary relationships, each built on a connection that lies outside the bounds of conventional romance. The exhibition is an examination of the profound intensity and depth of meaning most often associated with “true love,” but found instead through bonds based in work, friendship, religion, service, mentorship, community, and family — as well as between people and themselves, places, objects, and animals. -

Optical Illusions “What You See Is Not What You Get”

Optical Illusions “What you see is not what you get” The purpose of this lesson is to introduce students to basic principles of visual processing. Much of the lesson revolves around the use of visual illusions and interactive demonstrations with the students. The overarching theme of this lesson is that perception and sensation are not necessarily the same, and that optical illusions are a way for us to study the way that our visual system works. Furthermore, there are cells in the visual system that specifically respond to particular aspects of visual stimuli, and these cells can become fatigued. Grade Level: 3-12 Presentation time: 15-30 minutes, depending on which activities are chosen Lesson plan organization: Each lesson plan is divided into three sections: Introducing the lesson, Conducting the lesson, and Concluding the lesson. Each lesson has specific principles with associated figures, class discussion (D), and learning activities (A). This lesson plan is provided by the Neurobiology and Behavior Community Outreach Team at the University of Washington: http://students.washington.edu/watari/neuroscience/k12/LessonPlans.html 1 Materials: Computer to display some optical illusions (optional) Checkerboard illusion: Provided on page 8 or available online with explanation at http://web.mit.edu/persci/people/adelson/checkershadow_illusion.html Lilac chaser movie: http://www.scientificpsychic.com/graphics/ as an animated gif or http://www.michaelbach.de/ot/col_lilacChaser/index.html as Adobe Flash and including scientific explanation -

Mothers Grimm Kindle

MOTHERS GRIMM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Danielle Wood | 224 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Allen & Unwin | 9781741756746 | English | St Leonards, Australia Mothers Grimm PDF Book Showing An aquatic reptilian-like creature that is an exceptional swimmer. They have a temper that they control and release to become effective killers, particularly when a matter involves a family member or loved one. She took Nick to Weston's car and told Nick that he knew Adalind was upstairs with Renard, and the two guys Weston sent around back knew too. When Wu asks how she got over thinking it was real, she tells him that it didn't matter whether it was real, what mattered was losing her fear of it. Dick Award Nominee I found the characters appealing, and the plot intriguing. This wesen is portrayed as the mythological basis for the Three Little Pigs. The tales are very dark, and while the central theme is motherhood, the stories are truly about womanhood, and society's unrealistic and unfair expectations of all of us. Paperback , pages. The series presents them as the mythological basis for The Story of the Three Bears. In a phone call, his parents called him Monroe, seeming to indicate that it is his first name. The first edition contained 86 stories, and by the seventh edition in , had unique fairy tales. Danielle is currently teaching creative writing at the University of Tasmania. The kiss of a musai secretes a psychotropic substance that causes obsessive infatuation. View all 3 comments. He asks Sean Renard, a police captain, to endorse him so he would be elected for the mayor position. -

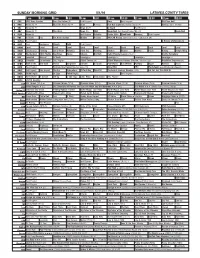

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION

Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION Trevor Jones Geoscience Australia 1.1 Cities Project Perth Cities Project Perth is a natural hazard risk assessment study of the city of Perth by Geoscience Australia (GA) and its Federal, State and Local collaborators. Cities Project Perth has produced authoritative knowledge on the risks from sudden-onset natural hazards in Australia’s fourth largest city and the capital of the state of Western Australia (WA). Cities Project Perth is the most recent multi-hazard risk assessment undertaken by GA and collaborating agencies (notably the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) and local governments), following earlier studies of the Queensland cities of Cairns (Granger et al., 1999), Mackay (Middelmann and Granger, editors, 2000), Gladstone (Granger and Michael-Leiba, editors, 2001) and South-East Queensland (Granger and Hayne, editors, 2001). GA also published the single- hazard report Earthquake Risk in Newcastle and Lake Macquarie, New South Wales (Dhu and Jones, editors, 2002). This study is aimed at estimating the impact on the Perth community of several sudden-onset natural hazards. The natural hazards considered are both meteorological and terrestrial in origin. The hazards investigated most comprehensively are riverine floods in the Swan and Canning Rivers, severe winds in metropolitan Perth, and earthquakes in the Perth region. Some socioeconomic factors affecting the capacity of the citizens of Perth to recover from natural disaster events have been analysed and the WA data compared with data from other Australian states. Additionally, new estimates of earthquake hazard have been made in a zone of radius around 200 km from Perth, extending east into the central Wheatbelt. -

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia By: D.A. Cumming, D. Garratt, M. McCarthy, A. WoICe With <.:unlribuliuns from Albany Seniur High Schoul. M. Anderson. R. Howard. C.A. Miller and P. Worsley Octobel' 1995 @WAUUSEUM Report: Department of Matitime Archaeology, Westem Australian Maritime Museum. No, 98. Cover pholograph: A view of Halllelin Bay in iL~ heyday as a limber porl. (W A Marilime Museum) This study is dedicated to the memory of Denis Arthur Cuml11ing 1923-1995 This project was funded under the National Estate Program, a Commonwealth-financed grants scheme administered by the Australian HeriL:'lge Commission (Federal Government) and the Heritage Council of Western Australia. (State Govenlluent). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Heritage Council of Western Australia Mr lan Baxter (Director) Mr Geny MacGill Ms Jenni Williams Ms Sharon McKerrow Dr Lenore Layman The Institution of Engineers, Australia Mr Max Anderson Mr Richard Hartley Mr Bmce James Mr Tony Moulds Mrs Dorothy Austen-Smith The State Archive of Westem Australia Mr David Whitford The Esperance Bay HistOIical Society Mrs Olive Tamlin Mr Merv Andre Mr Peter Anderson of Esperance Mr Peter Hudson of Esperance The Augusta HistOIical Society Mr Steve Mm'shall of Augusta The Busselton HistOlical Societv Mrs Elizabeth Nelson Mr Alfred Reynolds of Dunsborough Mr Philip Overton of Busselton Mr Rupert Genitsen The Bunbury Timber Jetty Preservation Society inc. Mrs B. Manea The Bunbury HistOlical Society The Rockingham Historical Society The Geraldton Historical Society Mrs J Trautman Mrs D Benzie Mrs Glenis Thomas Mr Peter W orsley of Gerald ton The Onslow Goods Shed Museum Mr lan Blair Mr Les Butcher Ms Gaye Nay ton The Roebourne Historical Society. -

The Open Notebook’S Pitch Database Includes Dozens of Successful Pitch Letters for Science Stories

Selected Readings Prepared for the AAAS Mass Media Science & Engineering Fellows, May 2012 All contents are copyrighted and may not be used without permission. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION PART ONE: FINDING IDEAS 1. Lost and found: How great non-fiction writers discover great ideas—In this topical feature, TON guest contributor Brendan Borrell interviews numerous science writers about how they find ideas. (The short answer: In the darndest places.) 2. Ask TON: Saving string—Writers and editors provide advice on gathering ideas for feature stories. 3. Ask TON: From idea to story—Four experienced science writers share the questions they ask themselves when weighing whether a story idea is viable. 4. Ask TON: Finding international stories—Six well-traveled science writers share their methods for sussing out international stories. PART TWO: PITCHING 5. Ask TON: How to pitch—In this interview, writers and editors dispense advice on elements of a good pitch letter. 6. Douglas Fox recounts an Antarctic adventure—Doug Fox pitched his Antarctica story to numerous magazines, unsuccessfully, before finding a taker just before leaving on the expedition he had committed to months before. After returning home, that assignment fell through, and Fox pitched it one more time—to Discover, who bought the story. In this interview, Fox describes the lessons he learned in the pitching process; he also shares his pitch letters, both unsuccessful and successful (see links). 7. Pitching errors: How not to pitch—In this topical feature, Smithsonian editor Laura Helmuth conducts a roundtable conversation with six other editors in which they discuss how NOT to pitch. -

Cancer Forum

March 2006 Volume 30 Number 1 ISSN 0311-306X CANCER FORUM Contents nnn Forum: Psycho-oncology Overview 3 Jane Turner Psychosocial aspects of sexuality and fertility after a diagnosis of breast cancer 6 Belinda Thewes and Kate White The effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on cognitive functioning in early breast cancer: 10 implications for outcomes research and oncology practice Geoffrey F Beadle et al. Exercise in cancer recovery: an overview of the evidence 13 Sandra C Hayes and Beth Newman Psychosocial issues for people with advanced cancer: overcoming the research challenges 18 Penelope Schofield et al. Challenges experienced by informal caregivers in cancer 21 Afaf Girgis et al. Leading the way – best practice in psychosocial care for cancer patients 25 Karen Luxford and Jane Fletcher Translating psychosocial care: guidelines into action 28 Suzanne K Steginga et al. The Psycho-oncology Co-operative Research Group 32 Phyllis Butow and Rebecca Hagerty nnn Articles Diversity and availability of support groups 35 Laura Kirsten et al. Promoting shared decision making and informed choice for the early detection of prostate 38 cancer: development and evaluation of a GP education program Robyn Metcalfe et al. nnn Reports Support for research 43 Australian behavioural research in cancer 57 COSA Annual Scientific Meeting 2005 65 Crossing the boundaries: a new era in cancer consumer participation 65 nnn News and announcements 67 nnn Book reviews 70 nnn Calendar of meetings 81 CancerForum Volume 30 Number 1 March 2006 1 CANCER FORUM FORUM Psycho-oncology OVERVIEW Jane Turner n Department of Psychiatry, University of Queensland Email: [email protected] “I stared down her housedress as she bent over to bathe me. -

Madam Pele: Novel and Essay

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2006 Madam Pele: Novel and essay Jud L. House Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation House, J. L. (2006). Madam Pele: Novel and essay. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/37 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/37 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. USE OF THESIS The Use of Thesis statement is not included in this version of the thesis. -

28 June 1994

2341 ?Utgxutatwcp Qlorw Tuesday, 28 June 1994 THE PRESIDENT (Hon Clive Griffiths) took the Chair at 3.30 pm, and read prayers. STATEMENT BY THE LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION .ADDRESS-IN- REPLY Presentationto Governor - Non-attendance of OppositionMembers HON JOHN HALDEN (South Metropolitan - Leader of the Opposition) [3.31 pmil - by leave: The Opposition will be declining the offer to attend upon His Excellency on this occasion to present the Address-in-Reply speech. Last week's events clearly demonstrate why the Opposition has taken this action. I do not believe it will be of interest to the House to debate this matter again. BILLS (7) - ASSENT Messages from the Lieutenant Governor received and read notifying assent to the following Bills - 1. Secondary Education Authority Amendment Bill 2. Fisheries Amendment Bill 3. Pearling Amendment Bill 4. Totalisator Agency Board Betting Amendment Bill 5. State Bank of South Australia (Transfer of Undertaking) Bill 6. Fire Brigades Superannuation Amendment Bill 7. Local Government Amendment Bill PETITION - LOGGING OF HESTER STATE FOREST Departmentof Conservation and Land Management Proposal HON J.A. SCOTT (South Metropolitan) [3.35 pm]: I present the following petition signed by 13 citizens of Western Australia - To the Honourable the President and Members of the Legislative Council in Parliament assembled. We the undersigned, are very concerned at the management practices of the Department of Conservation and Land Management in the Bridgetown- Greenbushes Shire. We request the Legislative Council to -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction.