1 Hide and Seek in the Deer's Trap: Language Concealment and Linguistic Camouflage in Timor Leste Aone Van Engelenhoven Leiden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCHAPPER, Antoinette and Emilie WELLFELT. 2018. 'Reconstructing

Reconstructing contact between Alor and Timor: Evidence from language and beyond a b Antoinette SCHAPPER and Emilie WELLFELT LACITO-CNRSa, University of Colognea, and Stockholm Universityb Despite being separated by a short sea-crossing, the neighbouring islands of Alor and Timor in south-eastern Wallacea have to date been treated as separate units of linguistic analysis and possible linguistic influence between them is yet to be investigated. Historical sources and oral traditions bear witness to the fact that the communities from both islands have been engaged with one another for a long time. This paper brings together evidence of various types including song, place names and lexemes to present the first account of the interactions between Timor and Alor. We show that the groups of southern and eastern Alor have had long-standing connections with those of north-central Timor, whose importance has generally been overlooked by historical and linguistic studies. 1. Introduction1 Alor and Timor are situated at the south-eastern corner of Wallacea in today’s Indonesia. Alor is a small mountainous island lying just 60 kilometres to the north of the equally mountainous but much larger island of Timor. Both Alor and Timor are home to a mix of over 50 distinct Papuan and Austronesian language-speaking peoples. The Papuan languages belong to the Timor-Alor-Pantar (TAP) family (Schapper et al. 2014). Austronesian languages have been spoken alongside the TAP languages for millennia, following the expansion of speakers of the Austronesian languages out of Taiwan some 3,000 years ago (Blust 1995). The long history of speakers of Austronesian and Papuan languages in the Timor region is a topic in need of systematic research. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Report of Findings on the Proposed Iralalaro Hydro-Electric Power Scheme, Timor-Leste

REPORT OF FINDINGS ON THE PROPOSED IRALALARO HYDRO-ELECTRIC POWER SCHEME, TIMOR-LESTE A report to the Haburas Foundation and the Australian Conservation Foundation by Susan White Nicholas White Greg Middleton January 2006 Mainina sinkhole, where the Irasiquero river disappears into the karst REPORT OF FINDINGS ON THE PROPOSED IRALALARO HYDRO-ELECTRIC POWER SCHEME, TIMOR-LESTE A report to the Haburas Foundation and the Australian Conservation Foundation Susan White B.A., B.Sc., M.Sc, Dip.Ed. (U. Melb), PhD (Latrobe U.)* Nicholas White B.Sc. (U. Melb), M.A. (Monash U.)* Greg Middleton B.Sc. (U. Sydney), Grad.Dip.Env.Stud. (U. Tas.) ** January 2006 * 123 Manningham Street, Parkville, Vic. 3052 Australia ** PO Box 269, Sandy Bay, Tas. 7006 Australia Report of findings on the proposed Iralalaro hydro-electric power scheme, Timor-Leste A report to the Haburas Foundation and the Australian Conservation Foundation © Susan White, Nicholas White and Greg Middleton 2006 Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this report may be reproduced by any process without written permission. The copyright holders grant unconditional permission to the Haburas Foundation and the Australian Conservation Foundation to reproduce and otherwise use any part of this report. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors acknowledge with thanks the assistance provided to them by the Australian Conservation Foundation and the Haburas Foundation in the preparation of this report. We also thank the many people who provided information and assisted us during a visit to the Iralalaro area in 2005. -

Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and Cultures

( J WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU ,. PATTIMURA UNIVERSITY and THE SUMMER INSTITUTE OP LINGUISTICS in cooperation with THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND CULTURE WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU Nyn D. Laidig, Edi tor PAT'I'IMORA tJlflVERSITY and THE SUMMER IRSTlTUTK OP LIRGOISTICS in cooperation with 'l'BB DBPAR".l'MElI'1' 01' BDUCATIOII ARD CULTURE Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and cultures Volume 6 Maluku Wyn D. Laidig, Editor Printed 1989 Ambon, Maluku, Indonesia Copies of this publication may be obtained from Summer Institute of Linguistics Kotak Pos 51 Ambon, Maluku 97001 Indonesia Microfiche copies of this and other publications of the Summer Institute of Linguistics may be obtained from Academic Book Center Summer Institute of Linguistics 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road l Dallas, TX 75236 U.S.A. ii PRAKATA Dengan mengucap syukur kepada Tuhan yang Masa Esa, kami menyambut dengan gembira penerbitan buku Workpapers in Indonesian Languages , and Cultures. Penerbitan ini menunjukkan adanya suatu kerjasama yang baik antara Universitas Pattimura deng~n Summer Institute of Linguistics; Maluku . Buku ini merupakan wujud nyata peran serta para anggota SIL dalam membantu masyarakat umumnya dan masyarakat pedesaan khususnya Diharapkan dengan terbitnya buku ini akan dapat membantu masyarakat khususnya di pedesaan, dalam meningkatkan pengetahuan dan prestasi mereka sesuai dengan bidang mereka masing-masing. Dengan adanya penerbitan ini, kiranya dapat merangsang munculnya penulis-penulis yang lain yang dapat menyumbangkan pengetahuannya yang berguna bagi kita dan generasi-generasi yang akan datang. Kami ucapkan ' terima kasih kepada para anggota SIL yang telah berupaya sehingga bisa diterbitkannya buku ini Akhir kat a kami ucapkan selamat membaca kepada masyarakat yang mau memiliki buku ini. -

Universidade De Brasília Instituto De Letras Departamento De Linguística, Português E Línguas Clássicas Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Linguística

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LINGUÍSTICA, PORTUGUÊS E LÍNGUAS CLÁSSICAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LINGUÍSTICA ASPECTOS GRAMATICAIS DA LÍNGUA MAKASAE DE TIMOR-LESTE: FONOLOGIA, MORFOLOGIA E SINTAXE Jessé Silveira Fogaça Brasília 2015 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LINGUÍSTICA, PORTUGUÊS E LÍNGUAS CLÁSSICAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LINGUÍSTICA ASPECTOS GRAMATICAIS DA LÍNGUA MAKASAE DE TIMOR-LESTE: FONOLOGIA, MORFOLOGIA E SINTAXE Jessé Silveira Fogaça Tese apresentada ao Departamento de Linguística, Português e Línguas Clássicas da Universidade de Brasília, como parte dos requisitos para a obtenção do grau de Doutor em Linguística. Orientador: Profº. Dr. Hildo Honório do Couto Brasília - DF 2015 Jessé Silveira Fogaça ASPECTOS GRAMATICAIS DA LÍNGUA MAKASAE DE TIMOR-LESTE: Fonologia, Morfologia e Sintaxe Tese apresentada ao Departamento de Linguística, Português e Línguas Clássicas da Universidade de Brasília, como parte dos requisitos para a obtenção do grau de Doutor em Linguística. Brasília, 17 de novembro de 2015. Banca Examinadora: Prof. Dr. Hildo Honório do Couto (UnB/presidente) Profa. Dra. Kênia Mara de Freitas Siqueira – Membro (PMEL/UFG/Catalão) Profa. Dra. Elza Kioko Nakayama Nenoki do Couto – Membro (FL/UFG) Profa. Dra. Walquíria Neiva Praça – Membro (UnB/PPGL) Profa. Dra. Orlene Lúcia de Sabóia Carvalho – Membro (UnB/PPGL) Profa. Dra. Ulisdete Rodrigues de Souza – Membro suplente RESUMO A presente tese aborda aspectos da gramática da língua Makasae de Timor-Leste, mais precisamente sua fonologia, morfossintaxe e sintaxe. No primeiro capítulo é apresentado as aspectos teóricos e metodológicos que nortearam a produção desta pesquisa, bem como o procedimento de coleta de dados e pesquisa de campo. -

Papuan Malay – a Language of the Austronesian- Papuan Contact Zone

Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society JSEALS 14.1 (2021): 39-72 ISSN: 1836-6821, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52479 University of Hawaiʼi Press PAPUAN MALAY – A LANGUAGE OF THE AUSTRONESIAN- PAPUAN CONTACT ZONE Angela Kluge SIL International [email protected] Abstract This paper describes the contact features that Papuan Malay, an eastern Malay variety, situated in East Nusantara, the Austronesian-Papuan contact zone, displays under the influence of Papuan languages. This selection of features builds on previous studies that describe the different contact phenomena between Austronesian and non-Austronesian languages in East Nusantara. Four typical western Austronesian features that Papuan Malay is lacking or making only limited use of are examined in more detail: (1) the lack of a morphologically marked passive voice, (2) the lack of the clusivity distinction in personal pronouns, (3) the limited use of affixation, and (4) the limited use of the numeral-noun order. Also described in more detail are six typical Papuan features that have diffused to Papuan Malay: (1) the genitive-noun order rather than the noun-genitive order to express adnominal possession, (2) serial verb constructions, (3) clause chaining, and (4) tail-head linkage, as well as (5) the limited use of clause-final conjunctions, and (6) the optional use of the alienability distinction in nouns. This paper also briefly discusses whether the investigated features are also present in other eastern Malay varieties such as Ambon Malay, Maluku Malay and Manado Malay, and whether they are inherited from Proto-Austronesian, and more specifically from Proto-Malayic. By highlighting the unique features of Papuan Malay vis-à-vis the other East Nusantara Austronesian languages and placing the regional “adaptations” of Papuan Malay in a broader diachronic perspective, this paper also informs future research on Papuan Malay. -

Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and Cultures

( J WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU ,. PATTIMURA UNIVERSITY and THE SUMMER INSTITUTE OP LINGUISTICS in cooperation with THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND CULTURE WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU Nyn D. Laidig, Edi tor PAT'I'IMORA tJlflVERSITY and THE SUMMER IRSTlTUTK OP LIRGOISTICS in cooperation with 'l'BB DBPAR".l'MElI'1' 01' BDUCATIOII ARD CULTURE Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and cultures Volume 6 Maluku Wyn D. Laidig, Editor Printed 1989 Ambon, Maluku, Indonesia Copies of this publication may be obtained from Summer Institute of Linguistics Kotak Pos 51 Ambon, Maluku 97001 Indonesia Microfiche copies of this and other publications of the Summer Institute of Linguistics may be obtained from Academic Book Center Summer Institute of Linguistics 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road l Dallas, TX 75236 U.S.A. ii PRAKATA Dengan mengucap syukur kepada Tuhan yang Masa Esa, kami menyambut dengan gembira penerbitan buku Workpapers in Indonesian Languages , and Cultures. Penerbitan ini menunjukkan adanya suatu kerjasama yang baik antara Universitas Pattimura deng~n Summer Institute of Linguistics; Maluku . Buku ini merupakan wujud nyata peran serta para anggota SIL dalam membantu masyarakat umumnya dan masyarakat pedesaan khususnya Diharapkan dengan terbitnya buku ini akan dapat membantu masyarakat khususnya di pedesaan, dalam meningkatkan pengetahuan dan prestasi mereka sesuai dengan bidang mereka masing-masing. Dengan adanya penerbitan ini, kiranya dapat merangsang munculnya penulis-penulis yang lain yang dapat menyumbangkan pengetahuannya yang berguna bagi kita dan generasi-generasi yang akan datang. Kami ucapkan ' terima kasih kepada para anggota SIL yang telah berupaya sehingga bisa diterbitkannya buku ini Akhir kat a kami ucapkan selamat membaca kepada masyarakat yang mau memiliki buku ini. -

Deixis in Ambonese Malay

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2016): 79.57 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Deixis in Ambonese Malay Prihe Slamatin Letlora1, La Ode Achmad Suherman2 1, 2English Language Studies, Department of Cultural Sciences, Hasanuddin University Abstract: Ambonese Malay as one of the Austronesian language in Indonesia has shown so many deixis inside and it is varied. This study aimed to explain qualitatively kinds of deixis which usually used by Ambonese in their everyday communication. It is indicated that there are kinds of deixis appeared they are: 1) Personal deixis such as beta as first person singular, katong as first person plural, ale as second person singular, kamong as second person plural, “Caca, abang, bu, usi, akang, antua” as third person singular, and there is also “dorang” as third person plural. The 3rd person singular “antua” (and “angtua, ontua, ongtua”) is also a modifier of head nominals in a phrase, thereby adding an aspect of deference; 2) place deixis such as: “Tu, Ni, Sana, Kasana, Kamari, Kasitu”; 3) time deixis such as: “Oras, Beso-beso, Minggu Muka, Kamareng dolo, Eso lusa, Tula”; 4) discourse deixis such as: “tu, brikut, sini, mina”; 5) social deixis such as: “Bapa Raja, Tuang Guru.” Keywords: words, referent, discourse, context 1. Introduction determined by knowing the context in which they are used. Levinson [6] defined deixis as the ways in which languages Common share language which is hold by speaker and hearer encode or grammaticalize features of the context of utterance in one communication event is essential to support the or speech event and thus also concerns ways in which the effectiveness of information exchange. -

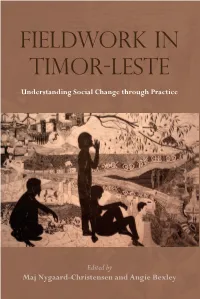

Fieldwork in Timor-Leste

Understanding Timor-Leste, on the ground and from afar (eds) and Bexley Nygaard-Christensen This ground-breaking exploration of research in Timor-Leste brings together veteran and early-career scholars who broadly Fieldwork in represent a range of fieldwork practices and challenges from colonial times to the present day. Here, they introduce readers to their experiences of conducting anthropological, historical and archival fieldwork in this new nation. The volume further Timor-Leste explores the contestations and deliberations that have been in Timor-Leste Fieldwork symptomatic of the country’s nation-building process, high- Understanding Social Change through Practice lighting how the preconceptions of development workers and researchers might be challenged on the ground. By making more explicable the processes of social and political change in Timor- Leste, the volume offers a critical contribution for those in the academic, policy and development communities working there. This is a must-have volume for scholars, other fieldworkers and policy-makers preparing to work in Timor-Leste, invaluable for those needing to understand the country from afar, and a fascinating read for anyone interested in the Timorese world. ‘Researchers and policymakers reading up on Timor Leste before heading to the field will find this handbook valuable. It is littered with captivating fieldwork stories. The heart-searching is at times searingly honest. Best of all, the book beautifully bridges the sometimes painful gap between Timorese researchers and foreign experts (who can be irritating know-alls). Academic anthropologists and historians will find much of value here, but the Timor policy community should appreciate it as well.’ – Gerry van Klinken, KITLV ‘This book is well worth reading by academics, activists and policy-makers in Timor-Leste and also those interested in the country’s development. -

Digging for the Roots of Language Death in Eastern Indonesia: the Cases of Kayeli and Hukumina

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 384 231 FL 023 076 AUTHOR Grimes, Charles E. TITLE Digging for the Roots of Language Death in Eastern Indonesia: The Cases of Kayeli and Hukumina. PUB DATE Jan 95 NOTE 19p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America (69th, New Orleans, LA, January 5-8, 1995). PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) Speeches /Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Diachronic Linguistics; Foreign Countries; *Geographic Location; *Indonesian Languages; *Language Role; Language Usage; Multilingualism; Power Structure; *Uncommonly Taught Languages IDENTIFIERS Indonesia ABSTRACT Looking at descriptive, comparative social and historical evidencB, this study explored factors contributing to language death for two languages formerly spoken on the Indonesian island of Buru. Field data were gathered from the last remaining speaker of Hukumina and from the last four speakers of Kayeli. A significant historical event that set in motion changing social dynamics was the forced relocation by the Dutch in 1656 of a number of coastal communities on this and surrounding islands, which severed the ties between Hukumina speakers and their traditional place of origin (with its access to ancestors and associated power). The same event brought a large number of outsiders to live around the Dutch fort near the traditional village of Kayeli, creating a multiethnic and multilingual community that gradually resulted in a shift to Malay for both Hukumina and Kayeli language communities. This contrasts with the Buru language still spoken as the primary means of daily communication in the island's interior. Also, using supporting evidence from other languages in the area, the study concludes that traditional notions of place and power are tightly linked to language ecology in this region. -

KA Adelaar, Muhadjir, Morphology of Jakarta Dialect, Affixation and Reduplication, Nusa II, Jakarta

Book Reviews - K.A. Adelaar, Muhadjir, Morphology of Jakarta dialect, affixation and reduplication, Nusa II, Jakarta: Badan Penyelenggara Seri Nusa, 1981, pp. xii + 117. - H.D. van Pernis, A.Ed. Schmidgall-Tellings, Contemporary Indonesian-English dictionary, a supplement to the standard Indonesian dictionaries with particular concentration on new words, expressions and meanings, Ohio University press, Chicago, Athens Ohio, London. 1981., Alan M. Stevens (eds.) - D.J. Prentice, Pierre Labrousse, Dictionnaire gýnýral indonýsien-francais (Cahier dýArchipel 15, 1984). Association Archipel, Paris. xxi + 934 pp. - H. Steinhauer, J.T. Collins, Ambonese Malay and creolization theory, Dewan bahasa dan pustaka, Kuala Lumpur 1980, xii + 84 pp., 2 maps. - A. Teeuw, Claudine Salmon, Literature in Malay by the Chinese of Indonesia; A provisional annotated bibliography. ýtudes Insulindiennes - Archipel 3. ýditions de la Maison des Sciences d lýHomme, Paris, 1981, 588 pp. In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 140 (1984), no: 4, Leiden, 522-540 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 02:37:30PM via free access BOEKBESPREKINGEN Muhadjir, Morphology of Jakarta dialect, affixation and re- duplication, Nusa II, Jakarta: Badan Penyelenggara Seri Nusa, 1981, pp. xii+ 117. K. A. ADELAAR Jakartanese is one of the major speech forms in Indonesia. Geographi- cally it is the language of Jakarta and its surroundings, but it is exercising a considerable influence on Indonesian as spoken in informal contacts by young urban people. It is the language of emotion and wit, and is of growing importance in newspapers and on radio and television. It has become the affective and emotional counterpart of Standard Indone- sian, which is feit to be far too formal and is mainly used for official speeches, official Communications in the media, and official documents. -

Introduction to the Papuan Languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Volume III Antoinette Schapper

Introduction to The Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Volume III Antoinette Schapper To cite this version: Antoinette Schapper. Introduction to The Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Volume III. Antoinette Schapper. Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Sketch grammars, 3, De Gruyter Mouton, pp.1-52, 2020. halshs-02930405 HAL Id: halshs-02930405 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02930405 Submitted on 4 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Introduction to The Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Volume III. Antoinette Schapper 1. Overview Documentary and descriptive work on Timor-Alor-Pantar (TAP) languages has proceeded at a rapid pace in the last 15 years. The publication of the volumes of TAP sketches by Pacific Linguistics has enabled the large volume of work on these languages to be brought together in a comprehensive and comparable way. In this third volume, five new descriptions of TAP languages are presented. Taken together with the handful of reference grammars (see Section 3), these volumes have achieved descriptive coverage of around 90% of modern-day TAP languages.