The Blur of Modernity: Essentialism, Affect and Everyday Life in Tokyo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VNA IFE ENG INNERS 0516 MJ.Indd

CHƯƠNG TRÌNH GIẢI TRÍ TRÊN CHUYẾN BAY INFLIGHT ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE T5 MAY - T6 JUNE 2016 MOVIE TELEVISION MUSIC GAMES Chào mừng Quý khách trên chuyến bay của Welcome aboard! Hãng hàng không quốc gia Việt Nam! Với hình ảnh bông sen vàng thân quen, LotuStar là thành LotuStar, your inflight entertainment guide, will give you details quả của quá trình không ngừng nâng cao của Vietnam of an exciting and diversified entertainment programme, representing Airlines với mong muốn mang đến cho quý khách Vietnam Airlines’ endeavour to make your flight a relaxing experience. những phút giây giải trí thư giãn trên chuyến bay. Lotus is an endearing emblem associated with Vietnam Airlines; Chữ “Star” – “Ngôi sao” được Vietnam Airlines lựa chọn đưa and “star”, while implying that many big movie stars and vào tên gọi của cuốn chương trình giải trí như một ẩn dụ cho audio stars will appear in their performances, implicitly hình ảnh các ngôi sao điện ảnh, ngôi sao ca nhạc sẽ xuất hiện mentions Vietnam Airlines’ plan to achieve a 4-star status trong các chương trình giải trí. “Ngôi sao”, hơn thế nữa, còn for all its services. That’s what is meant by LotuStar. đại diện cho mục tiêu mà Vietnam Airlines đang hướng tới: The pages of the booklet will guide you to the enjoyment chất lượng phục vụ quí khách ngày càng hoàn hảo hơn. of audio-visual entertainment that includes classic movies, Mỗi trang thông tin trong cuốn cẩm nang hứa hẹn mang đến cho Quý blockbusters, timeless and favourite musical compositions, khách một thế giới nghe-nhìn sôi động với các bộ phim điện ảnh kinh audio books and interesting games etc.. -

Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family

Thesis for Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family by Hiroko Umegaki Lucy Cavendish College Submitted November 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies provided by Apollo View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by 1 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit of the relevant Degree Committee. 2 Acknowledgments Without her ever knowing, my grandmother provided the initial inspiration for my research: this thesis is dedicated to her. Little did I appreciate at the time where this line of enquiry would lead me, and I would not have stayed on this path were it not for my family, my husband, children, parents and extended family: thank you. -

A 5 Day Tokyo Itinerary

What To Do In Tokyo - A 5 Day Tokyo Itinerary by NERD NOMADS NerdNomads.com Tokyo has been on our bucket list for many years, and when we nally booked tickets to Japan we planned to stay ve days in Tokyo thinking this would be more than enough. But we fell head over heels in love with this metropolitan city, and ended up spending weeks exploring this strange and fascinating place! Tokyo has it all – all sorts of excellent and corky museums, grand temples, atmospheric shrines and lovely zen gardens. It is a city lled with Japanese history, but also modern, futuristic neo sci- streetscapes that make you feel like you’re a part of the Blade Runner movie. Tokyo’s 38 million inhabitants are equally proud of its ancient history and culture, as they are of its ultra-modern technology and architecture. Tokyo has a neighborhood for everyone, and it sure has something for you. Here we have put together a ve-day Tokyo itinerary with all the best things to do in Tokyo. If you don’t have ve days, then feel free to cherry pick your favorite days and things to see and do, and create your own two or three day Tokyo itinerary. Here is our five day Tokyo Itinerary! We hope you like it! Maria & Espen Nerdnomads.com Day 1 – Meiji-jingu Shrine, shopping and Japanese pop culture Areas: Harajuku – Omotesando – Shibuya The public train, subway, and metro systems in Tokyo are superb! They take you all over Tokyo in a blink, with a net of connected stations all over the city. -

Tistic and Religious Aspects of Nosatsu (Senjafuda)

~TISTIC AND RELIGIOUS ASPECTS OF NOSATSU (SENJAFUD~ by MAYUMI TAK.ANASlU STEINMETZ A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 1985 iii Copyright Mayumi Takanashi Steinmetz 1985 iv An Abstract of the Thesis of Mayumi Takanashi Steinmetz for the degree of Master of Arts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 1985 Title: ARTISTIC AND RELIGIOUS ASPECTS OF NOSATSU (SENJAFUDA) Approved: Nosatsu is both a graphic art object and a religious object. Until very recently, scholars have ignored nosatsu because of its associations with superstition and low-class, uneducated ho.bbyists. Recently, however, a new interest in nosatsu has revived because of its connections to ukiyo-e. Early in its history, nosatsu was regarded as a means of showing devotion toward the bodhisattva.Kannon. However, during the Edo period, producing artistic nosatsu was emphasized. more than religious devotion. There was a revival of interest in nosatsu during the Meiji and Taisho periods, and its current popularity suggests a national Japanese nostalgia toward traditional Japan. Using the religious, anthropological, and art historical perspectives, this theses will examine nosatsu and the practices associated with it, discuss reasons for the changes from period to pe~iod, and explore the heritage and the changing values of the Japanese common people. V VITA NAME OF AUTHOR: Mayumi -

NOVEMBER 2015 Raising a Prodigy Starts with the Parents PAGE 92

COMIC RELIEF Vietnam’s Comic Book Industry Gets a Jumpstart PAGE 19 DINE WITH A VIEW Indulge in Japanese-Chinese Cuisine Overlooking the River PAGE 58 SAVAGE ISLAND Discover the Remotest Polynesian Island PAGE 80 WUNDERKIDS VIETNAM NOVEMBER 2015 Raising a Prodigy Starts With the Parents PAGE 92 Stories of the Sea 1 2 3 EVERYWHERE YOU GO Director XUAN TRAN Managing Director JIMMY VAN DER KLOET [email protected] Managing Editor CHRISTINE VAN [email protected] Deputy Editor JAMES PHAM This Month’s Cover [email protected] Location: Pullman Danang Beach Resort (www.pullman-danang.com) Associate Publisher KHANH NGUYEN [email protected] Editorial Intern ALEX GREEN Graphic Artist KEVIN NGUYEN [email protected] Located on Dong Khoi, the most beautiful street Staff Photographer NGOC TRAN [email protected] of Saigon, with balcony view to the Opera House For advertising please contact: NGAN NGUYEN [email protected] 090 279 7951 CHAU NGUYEN Our popular homemade style food and drinks [email protected] 091 440 0302 ƠI VIỆT NAM HANH (JESSIE) LE [email protected] NHÀ XUẤT BẢN THANH NIÊN 098 747 4183 Chịu trách nhiệm xuất bản: Giám đốc, Tổng biên tập HANNIE VO Nguyễn Xuân Trường [email protected] Biên tập: Quang Huy - Quang Hùng Thực hiện liên kết xuất bản: Metro Advertising Co.,Ltd 48 Hoàng Diệu, Phường 12, Quận 4 In lần thứ ba mươi hai, số lượng 6000 cuốn, khổ 21cm x 29,7cm Catina noodle Banana cake Lemongrass & Lime juice Catina drink Đăng ký KHXB: 2633 -2015/CXB/18-135/TN QĐXB số: 452/QĐ-TN General [email protected] Chế bản và in tại Nhà in Gia Định Nộp lưu chiểu tháng 11/2015 Inquiries [email protected] Website: www.oivietnam.com Welcome in. -

Joseonhakgyo, Learning Under North Korean Leadership: Transitioning from 1970 to Present*

https://doi.org/10.33728/ijkus.2020.29.1.007 International Journal of Korean Unification Studies Vol. 29, No. 1, 2020, 161-188. Joseonhakgyo, Learning under North Korean Leadership: Transitioning from 1970 to Present* Min Hye Cho** This paper analyzes English as a Foreign Language (EFL) textbooks used during North Korea’s three leaderships: 1970s, 1990s and present. The textbooks have been used at Korean ethnic schools, Joseonhakgyo (朝鮮学校), which are managed by the Chongryon (總聯) organization in Japan. The organization is affiliated with North Korea despite its South Korean origins. Given North Korea’s changing influence over Chongryon’s education system, this study investigates how Chongryon Koreans’ view on themselves has undergone a transition. The textbooks’ content that have been used in junior high school classrooms (students aged between thirteen and fifteen years) are analyzed. Selected texts from these textbooks are analyzed critically to delineate the changing views of Chongryon Koreans. The findings demonstrate that Chongryon Koreans have changed their perspective from focusing on their ties to North Korea (1970s) to focusing on surviving as a minority group (1990s) to finally recognising that they reside permanently in Japan (present). Keywords: EFL textbooks, Korean ethnic school, minority education, North Koreans in Japan, North Korean leadership ** Acknowledgments: The author would like to acknowledge the generous and thoughtful support of the staff at Hagusobang (Chongryon publishing company), including Mr Nam In Ryang, Ms Kyong Suk Kim and Ms Mi Ja Moon; Ms Malryo Jang, an English teacher at Joseonhakgyo; and Mr Seong Bok Kang at Joseon University in Tokyo. They have consistently provided primary resource materials, such as Chongryon EFL textbooks, which made this research project possible. -

Vaitoskirjascientific MASCULINITY and NATIONAL IMAGES IN

Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki, Finland SCIENTIFIC MASCULINITY AND NATIONAL IMAGES IN JAPANESE SPECULATIVE CINEMA Leena Eerolainen DOCTORAL DISSERTATION To be presented for public discussion with the permission of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Helsinki, in Room 230, Aurora Building, on the 20th of August, 2020 at 14 o’clock. Helsinki 2020 Supervisors Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Bart Gaens, University of Helsinki, Finland Pre-examiners Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Rikke Schubart, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark Opponent Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Custos Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Copyright © 2020 Leena Eerolainen ISBN 978-951-51-6273-1 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-6274-8 (PDF) Helsinki: Unigrafia, 2020 The Faculty of Arts uses the Urkund system (plagiarism recognition) to examine all doctoral dissertations. ABSTRACT Science and technology have been paramount features of any modernized nation. In Japan they played an important role in the modernization and militarization of the nation, as well as its democratization and subsequent economic growth. Science and technology highlight the promises of a better tomorrow and future utopia, but their application can also present ethical issues. In fiction, they have historically played a significant role. Fictions of science continue to exert power via important multimedia platforms for considerations of the role of science and technology in our world. And, because of their importance for the development, ideologies and policies of any nation, these considerations can be correlated with the deliberation of the role of a nation in the world, including its internal and external images and imaginings. -

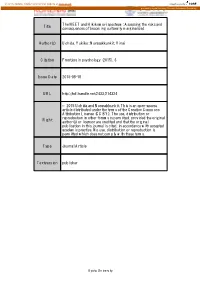

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

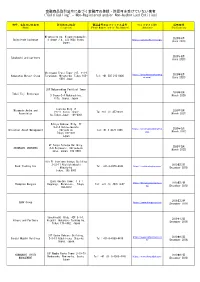

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered And/Or Non-Authorized Entities)

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered and/or Non-Authorized Entities) 商号、名称又は氏名等 所在地又は住所 電話番号又はファックス番号 ウェブサイトURL 掲載時期 (Name) (Location) (Phone Number and/or Fax Number) (Website) (Publication) Miyakojima-ku, Higashinodamachi, 2020年6月 SwissTrade Exchange 4-chōme−7−4, 534-0024 Osaka, https://swisstrade.exchange/ (June 2020) Japan 2020年6月 Takahashi and partners (June 2020) Shiroyama Trust Tower 21F, 4-3-1 https://www.hamamatsumerg 2020年6月 Hamamatsu Merger Group Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105- Tel: +81 505 213 0406 er.com/ (June 2020) 0001 Japan 28F Nakanoshima Festival Tower W. 2020年3月 Tokai Fuji Brokerage 3 Chome-2-4 Nakanoshima. (March 2020) Kita. Osaka. Japan Toshida Bldg 7F Miyamoto Asuka and 2020年3月 1-6-11 Ginza, Chuo- Tel:+81 (3) 45720321 Associates (March 2021) ku,Tokyo,Japan. 104-0061 Hibiya Kokusai Bldg, 7F 2-2-3 Uchisaiwaicho https://universalassetmgmt.c 2020年3月 Universal Asset Management Chiyoda-ku Tel:+81 3 4578 1998 om/ (March 2022) Tokyo 100-0011 Japan 9F Tokyu Yotsuya Building, 2020年3月 SHINBASHI VENTURES 6-6 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku (March 2023) Tokyo, Japan, 102-0083 9th Fl Onarimon Odakyu Building 3-23-11 Nishishinbashi 2019年12月 Rock Trading Inc Tel: +81-3-4579-0344 https://rocktradinginc.com/ Minato-ku (December 2019) Tokyo, 105-0003 Izumi Garden Tower, 1-6-1 https://thompsonmergers.co 2019年12月 Thompson Mergers Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Tel: +81 (3) 4578 0657 m/ (December 2019) 106-6012 2019年12月 SBAV Group https://www.sbavgroup.com (December 2019) Sunshine60 Bldg. 42F 3-1-1, 2019年12月 Hikaro and Partners Higashi-ikebukuro Toshima-ku, (December 2019) Tokyo 170-6042, Japan 31F Osaka Kokusai Building, https://www.smhpartners.co 2019年12月 Sendai Mubuki Holdings 2-3-13 Azuchi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tel: +81-6-4560-4410 m/ (December 2019) Osaka, Japan. -

TOKYO TRAIN & SUBWAY MAP JR Yamanote

JR Yamanote Hibiya line TOKYO TRAIN & SUBWAY MAP Ginza line Chiyoda line © Tokyo Pocket Guide Tozai line JR Takasaka Kana JR Saikyo Line Koma line Marunouchi line mecho Otsuka Sugamo gome Hanzomon line Tabata Namboku line Ikebukuro Yurakucho line Shin- Hon- Mita Line line A Otsuka Koma Nishi-Nippori Oedo line Meijiro Sengoku gome Higashi Shinjuku line Takada Zoshigaya Ikebukuro Fukutoshin line nobaba Todai Hakusan Mae JR Joban Asakusa Nippori Line Waseda Sendagi Gokokuji Nishi Myogadani Iriya Tawara Shin Waseda Nezu machi Okubo Uguisu Seibu Kagurazaka dani Inaricho JR Shinjuku Edo- Hongo Chuo gawa San- Ueno bashi Kasuga chome Naka- Line Higashi Wakamatsu Okachimachi Shinjuku Kawada Ushigome Yushima Yanagicho Korakuen Shin-Okachi Ushigome machi Kagurazaka B Shinjuku Shinjuku Ueno Hirokoji Okachimachi San-chome Akebono- Keio bashi Line Iidabashi Suehirocho Suido- Shin Gyoen- Ocha Odakyu mae Bashi Ocha nomizu JR Line Yotsuya Ichigaya no AkihabaraSobu Sanchome mizu Line Sendagaya Kodemmacho Yoyogi Yotsuya Kojimachi Kudanshita Shinano- Ogawa machi Ogawa Kanda Hanzomon Jinbucho machi Kokuritsu Ningyo Kita Awajicho -cho Sando Kyogijo Naga Takebashi tacho Mitsu koshi Harajuku Mae Aoyama Imperial Otemachi C Meiji- Itchome Kokkai Jingumae Akasaka Gijido Palace Nihonbashi mae Inoka- Mitsuke Sakura Kaya Niju- bacho shira Gaien damon bashi bacho Tameike mae Tokyo Line mae Sanno Akasaka Kasumi Shibuya Hibiya gaseki Kyobashi Roppongi Yurakucho Omotesando Nogizaka Ichome Daikan Toranomon Takaracho yama Uchi- saiwai- Hachi Ebisu Hiroo Roppongi Kamiyacho -

Full Download

VOLUME 1: BORDERS 2018 Published by National Institute of Japanese Literature Tokyo EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor IMANISHI Yūichirō Professor Emeritus of the National Institute of Japanese 今西祐一郎 Literature; Representative Researcher Editors KOBAYASHI Kenji Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 小林 健二 SAITō Maori Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 齋藤真麻理 UNNO Keisuke Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 海野 圭介 Literature KOIDA Tomoko Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 恋田 知子 Literature Didier DAVIN Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese ディディエ・ダヴァン Literature Kristopher REEVES Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese クリストファー・リーブズ Literature ADVISORY BOARD Jean-Noël ROBERT Professor at Collège de France ジャン=ノエル・ロベール X. Jie YANG Professor at University of Calgary 楊 暁捷 SHIMAZAKI Satoko Associate Professor at University of Southern California 嶋崎 聡子 Michael WATSON Professor at Meiji Gakuin University マイケル・ワトソン ARAKI Hiroshi Professor at International Research Center for Japanese 荒木 浩 Studies Center for Collaborative Research on Pre-modern Texts, National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) National Institutes for the Humanities 10-3 Midori-chō, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-0014, Japan Telephone: 81-50-5533-2900 Fax: 81-42-526-8883 e-mail: [email protected] Website: https//www.nijl.ac.jp Copyright 2018 by National Institute of Japanese Literature, all rights reserved. PRINTED IN JAPAN KOMIYAMA PRINTING CO., TOKYO CONTENTS -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr.