Big Business Litigation in US Federal Courts, 1971–1991

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latinos | Creating Shopping Centers to Meet Their Needs May 23, 2014 by Anthony Pingicer

Latinos | Creating shopping centers to meet their needs May 23, 2014 by Anthony Pingicer Source: DealMakers.net One in every six Americans is Latino. Since 1980, the Latino population in the United States has increased dramatically from 14.6 million, per the Census Bureau, to exceeding 50 million today. This escalation is not just seen in major metropolitan cities and along the America-Mexico border, but throughout the country, from Cook County, Illinois to Miami-Dade, Florida. By 2050, the Latino population is projected to reach 134.8 million, resulting in a 30.2 percent share of the U.S. population. Latinos are key players in the nation’s economy. While the present economy benefits from Latinos, the future of the U.S. economy is most likely to depend on the Latino market, according to “State of the Hispanic Consumer: The Hispanic Market Imperative,” a report released by Nielsen, an advertising and global marketing research company. According to the report, the Latino buying power of $1 trillion in 2010 is predicted to see a 50 percent increase by next year, reaching close to $1.5 trillion in 2015. The U.S. Latino market is one of the top 10 economies in the world and Latino households in America that earn $50,000 or more are growing at a faster rate than total U.S. households. As for consumption trends, Latinos tend to spend more money per shopping trip and are also expected to become a powerful force in home purchasing during the next decade. Business is booming for Latinos. According to a study by the Partnership for a New Economy, the number of U.S. -

New Company to Take Over Dozens of National Stores Outposts

NEWSPAPER 2ND CLASS $2.99 VOLUME 74, NUMBER 49 NOVEMBER 30–DECEMBER 6, 2018 THE VOICE OF THE INDUSTRY FOR 73 YEARS New Company to Take Over Dozens of National Stores Outposts By Deborah Belgum Executive Editor After filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in Au- gust, National Stores has found a way to keep some of its stores open after announcing it was closing all of them. Second Avenue Capital Partners, a Schottenstein- family affiliate that is a finance company, said on Nov. 27 it closed a $20-million, asset-based credit facility to fund the purchase and ongoing working capital for a new entity called Fallas Stores. Fallas Stores will be purchasing 85 stores from National Stores during a bankruptcy-mandated auction, the company said. In October, National Stores said it was closing 184 of its stores, which operate under the nameplates Fallas, Fa- llas-Paredes, Factory 2-U and Falas in Puerto Rico. The new Fallas Stores will operate under the same model as the National Stores, selling discounted apparel and other merchandise and buying from the same vendors who sold National page 8 Black Friday Sees a Dip Over Last Year but Still Considered Strong By Andrew Asch Retail Editor While more than 165 million Americans shopped online or in stores during the Black Friday weekend—which now extends from Thanksgiving Day through Cyber Monday— the numbers were down by nearly 10 million shoppers from 2017. In 2017, some 174 million shoppers hit the malls or the Web to make purchases. This year, the National Retail Federation said the aver- age consumer spent $313.29 on gifts and holiday items dur- ing the five-day period. -

CHLA 2017 Annual Report

Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Annual Report 2017 About Us The mission of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is to create hope and build healthier futures. Founded in 1901, CHLA is the top-ranked children’s hospital in California and among the top 10 in the nation, according to the prestigious U.S. News & World Report Honor Roll of children’s hospitals for 2017-18. The hospital is home to The Saban Research Institute and is one of the few freestanding pediatric hospitals where scientific inquiry is combined with clinical care devoted exclusively to children. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is a premier teaching hospital and has been affiliated with the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California since 1932. Table of Contents 2 4 6 8 A Message From the Year in Review Patient Care: Education: President and CEO ‘Unprecedented’ The Next Generation 10 12 14 16 Research: Legislative Action: Innovation: The Jimmy Figures of Speech Protecting the The CHLA Kimmel Effect Vulnerable Health Network 18 20 21 81 Donors Transforming Children’s Miracle CHLA Honor Roll Financial Summary Care: The Steven & Network Hospitals of Donors Alexandra Cohen Honor Roll of Friends Foundation 82 83 84 85 Statistical Report Community Board of Trustees Hospital Leadership Benefit Impact Annual Report 2017 | 1 This year, we continued to shine. 2 | A Message From the President and CEO A Message From the President and CEO Every year at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is by turning attention to the hospital’s patients, and characterized by extraordinary enthusiasm directed leveraging our skills in the arena of national advocacy. -

Food Distribution in the United States the Struggle Between Independents

University of Pennsylvania Law Review FOUNDED 1852 Formerly American Law Register VOL. 99 JUNE, 1951 No. 8 FOOD DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES, THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN INDEPENDENTS AND CHAINS By CARL H. FULDA t I. INTRODUCTION * The late Huey Long, contending for the enactment of a statute levying an occupation or license tax upon chain stores doing business in Louisiana, exclaimed in a speech: "I would rather have thieves and gangsters than chain stores inLouisiana." 1 In 1935, a few years later, the director of the National Association of Retail Grocers submitted a statement to the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives, I Associate Professor of Law, Rutgers University School of Law. J.U.D., 1931, Univ. of Freiburg, Germany; LL. B., 1938, Yale Univ. Member of the New York Bar, 1941. This study was originally prepared under the auspices of the Association of American Law Schools as one of a series of industry studies which the Association is sponsoring through its Committee on Auxiliary Business and Social Materials for use in courses on the antitrust laws. It has been separately published and copyrighted by the Association and is printed here by permission with some slight modifications. The study was undertaken at the suggestion of Professor Ralph F. Fuchs of Indiana University School of Law, chairman of the editorial group for the industry studies, to whom the writer is deeply indebted. His advice during the preparation of the study and his many suggestions for changes in the manuscript contributed greatly to the improvement of the text. Acknowledgments are also due to other members of the committee, particularly Professors Ralph S. -

Additional Case Information

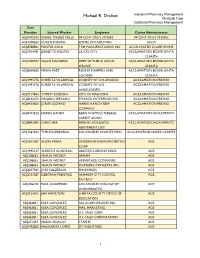

Michael R. Drobot Industrial Pharmacy Management MediLab Corp California Pharmacy Management Case Number Injured Worker Employer Claims Administrator ADJ7472102 ISMAEL TORRES VALLE 99 CENT ONLY STORES 99 CENT ONLY STORES ADJ1308567 CURTIS RIGGINS EMPIRE DISTRIBUTORS ACCA ADJ8768841 MARTIN AVILA TRM MANUFACTURING INC ACCELERATED CLAIMS IRVINE ADJ7014781 JEANETTE WILSON LA COUNTY ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA CLARITA ADJ7200937 SUSAN NAVARRO DEPT OF PUBLIC SOCIAL ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA SERVICE CLARITA ADJ8009655 MARIA PAEZ RUSKIN DAMPERS AND ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA LOUVERS CLARITA ADJ1993776 ROBERTA VILLARREAL COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ1993776 ROBERTA VILLARREAL COUNTY OF LOS ACCLAMATION FRESNO ANGELES/DPSS ADJ7117844 TOMMY ROBISON CITY OF MARICOPA ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ8162473 ONORIO SERRANO ESPARZA ENTERPRISES INC ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ8420600 JORGE LOZANO HARRIS RANCH BEEF ACCLAMATION FRESNO COMPANY ADJ8473212 DAREN HANDY KERN SCHOOLS FEDERAL ACCLAMATION SACRAMENTO CREDIT UNION ADJ8845092 CHAO HER FRESNO MOSQUITO ACCLAMATION SACRAMENTO ABATEMENT DIST ADJ1361532 THELMA JENNINGS LOS ANGELES COUNTY/DPSS ACCLAMATION SANTA CLARITA ADJ1611037 ALICIA MORA ANDERSON BARROWS METALS ACE CORP ADJ1995137 ALBERTO GUNDRAN ABLESTIK LABORATORIES ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY AMPAM ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY AMPAM RCR COMPANIES ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY PLUMBING CONCEPTS INC ACE ADJ2237965 JOSE CALDERON FMI EXPRESS ACE ADJ2353287 DEBORAH PRENTICE ANAHEIM CITY SCHOOL ACE DISTRICT ADJ246218 PAUL LIGAMMARI LOS ANGELES COLLEGE OF ACE CHIROPRACTIC -

(NAARS): Official Listing of the Corporations Comprising the 1972 Annual Report File

University of Mississippi eGrove American Institute of Certified Public Guides, Handbooks and Manuals Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection 1972 National Automated Accounting Research System (NAARS): Official Listing of the Corporations Comprising the 1972 Annual Report File American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_guides Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), "National Automated Accounting Research System (NAARS): Official Listing of the Corporations Comprising the 1972 Annual Report File" (1972). Guides, Handbooks and Manuals. 703. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_guides/703 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Guides, Handbooks and Manuals by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NATIONAL AUTOMATED ACCOUNTING RESEARCH SYSTEM NAARS OFFICIAL LISTING OF THE CORPORATIONS COMPRISING THE 1972 ANNUAL REPORT FILE PAGE 1 1972 ANNUAL REPORT FILE ALPHABETICAL LISTING COMPANY NAME SIC S EX B S DATE AUDITOR A & E PLASTIK PAK CO., INC. 309 ASE 12-31-72 PMM A.B. DICK COMPANY 508 OTC 12-31-72 AA A.E. STALEY MANUFACTURING COMPANY 204 NySE 09-30-72 HS a.g. Edwards & sons inc 621 ASE 02-28-73 TR a.h. rOBins company, incorporated 283 NYSE 12-31-72 a.m. pullen & company a.M. castle & co. 509 ASE 12-31-72 AA a.o. smith corporation 371 NYSE 12-31-72 ay a.p.s. -

This Sixty-Day Notice of Intent to Sue for Violation of the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986 Is Addressed To

SIXTY-DAY NOTICE OF INTENT TO SUE FOR VIOLATION OF THE SAFE DRINKING WATER AND TOXIC ENFORCEMENT ACT OF 1986 {Cal. Health <& Safety Code § 25249.5, et seq.)("Proposition 65") May 31, 2018 This Sixty-Day Notice Of Intent To Sue For Violation Of The Safe Drinking Water And Toxic Enforcement Act Of 1986 is addressed to: Michael Fallas, President Or Current President / CEO National Stores, Inc. dba Fallas, Fallas Paredes, Fallas Discount Stores, Factory 2-U, Factory 2-U Stores Inc., Factory 2 U, Anna's Linen's by Fallas, M M & J Ventures, Michael/Moses/Joseph Fallas 15001 S. Figueroa Street Gardena, CA 90248 Michael Fallas, CEO Michael Fallas, CEO or Michael Fallas, CEO or Or Current President/CEO Current President/CEO Current President/CEO FP Stores Inc., dba Fallas and National Stores, Inc., dba Michael/Moses/Joseph Fallas, Fallas Kids Michael/Moses/Joseph Fallas DBA M M & J Ventures 15001 S. Figueroa Street 6633 Van Nuys Blvd 6633 Van Nuys Blvd Gardena, CA 90248 Van Nuys, CA 91405 Van Nuys, CA 91405 Michael Fallas, CEO Michael Fallas, CEO Michael Fallas, CEO or Or Current President/CEO Or Current President/CEO Current President/CEO J and M Sales Inc., dba Fallas, J&M Sales Inc. dba La Moda For J & M Sales Corporation Factory 2 U,Factory 2U Kids Inc. 15001 S. Figueroa Street 15001 S. Figueroa Street 15001 S. Figueroa Street Gardena, CA 90248 Gardena, CA 90248 Gardena, CA 90248 Michael Fallas, CEO or Joseph Fallas, CEO Michael Fallas, CEO or Current President/CEO Or Current President/CEO Current President/CEO Michael/Moses/Joseph Fallas, dba Fallas Management, Inc. -

List of Stocks Registered on a National Securities Exchange and of Redeemable Securities of Certain Investment Companies

List of Stocks Registered on a National Securities Exchange and of Redeemable Securities of Certain Investment Companies AS OF JUNE 30, 1965 (PREPARED FOR PURPOSES OF REGULATION U) BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM WASHINGTON SEPTEMBER 1965 This publication was digitized and made available by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas' Historical Library ([email protected]) Foreword This list is divided into two parts: Part I— Stocks Registered on a National Securities Exchange.............................................................. P* 4 Part II—Redeemable Securities Issued by Open-End Investment Companies Whose Assets Customarily Include Stocks Registered on a National Securities Exchange ..............................p. 23 The purpose of the list is to facilitate compliance by banks with the provisions of Regulation U of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, entitled “Loans by banks for the purpose of pur chasing or carrying stocks registered on a national securities exchange." Regulation U applies to all banks in the United States, including both members and nonmembers of the Federal Reserve System. Any inquiry relating to the regulation should be addressed to the Federal Reserve Bank of the district in which the inquiry arises. Section 221.3 of Regulation U provides as follows: “(b) (2) A loan for the purpose of purchasing or carrying a 'redeemable security’ (i.e. a redeemable proportionate interest in the issuer’s assets) issued by an 'open-end company’, as defined in the Investment Company Act of 1940, whose assets customarily include stocks registered on a national securities exchange, shall be deemed to be for the purpose of purchasing or carrying a stock so registered. -

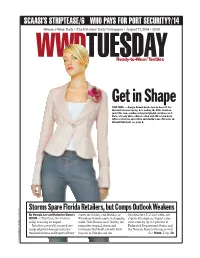

Get in Shape NEW YORK — Giorgio Armani Knows How to Keep Fit

SCAASI’S STRIPTEASE/6 WHO PAYS FOR PORT SECURITY?/14 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’TUESDAY Daily Newspaper • August 17, 2004 • $2.00 Ready-to-Wear/Textiles Get in Shape NEW YORK — Giorgio Armani knows how to keep fit. For Armani Collezioni spring, he’s making the little shrunken jacket his own, sending out myriad playful variations on it. Here, a breezy wide-collared cotton and silk version worn with a cotton top and cotton and elastin jeans. For more on Armani Collezioni, see page 8. Storms Spare Florida Retailers, but Comps Outlook Weakens By Georgia Lee and Katherine Bowers stores on Sunday and Monday as Southeastern U.S. last week, are Y PORTIA PETERS Y PORTIA ATLANTA — This time, the weather Floridians found respite in shopping expected to depress August same- really is having an impact. malls. Still, Bonnie and Charley, the store sales by up to 2 percent at Retailers generally escaped any respective tropical storm and Federated Department Stores and major physical damage from the hurricane that dealt a deadly blow the Neiman Marcus Group, as well weekend storms and reported busy to parts of Florida and the See Storm, Page 18 PHOTO BY DAVID TURNER; HAIR AND MAKEUP B DAVID PHOTO BY 2 WWD, TUESDAY, AUGUST 17, 2004 WWW.WWD.COM WWDTUESDAY Eskenasi to Exit Saks Inc. Ready-to-Wear/Textiles By David Moin Eskenasi could not be reached to learn about GENERAL her plans. The impact of Hurricane Charley and Tropical Storm Bonnie on the NEW YORK — Saks Inc.’s aggressive private label “I’m sure she can write her own ticket wher- 1 Southeast is expected to hurt August sales at Federated and Neiman’s. -

Food Retailing and Processing Practices

6,7 FOOD RETAILING AND PROCESSING PRACTICES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON CONSUMER ECONOMICS OF THE JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES NINETY-THIRD CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MAY 21, 1974 Printed for the use of the Joint Economic Committee 0 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 41-662 WASHINGTON : 1974 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 -Price $2.75 I I JOINT ECONOMIC COMMTUITTEE Cong.) (Created pursuant to see. 5(a) of Public Law 304, 79th WRIGHT PATMAN, Texas, Chairman WILLIAM PROXMIRE, Wisconsin, Vice Chairman HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SENATE Alabama RICHARD BOLLING, Missouri JOHN SPARKMAN, Arkansas HENRY S. REUSS, Wisconsin J. W. FULBRIGHT, RIBICOFF, Connecticut MARTHA W. GRIFFITHS, Michigan ABRAHAM H. HUMPHREY, Minnesota WILLIAM S. MOORHEAD, Pennsylvania HUBERT BENTSEN, JR., Texas HUGH L. CAREY, New York LLOYD M. JAVITS, New York WILLIAM B. WIDNALL, New Jersey JACOB K. H. PERCY, Illinois BARBER B. CONABLE, JR., New York CHARLES PEARSON, Kansas CLARENCE J. BROWN, Ohio JAMES B. SCHWEIKER, Pennsylvania BEN B. BLACKBURN, Georgia RICHARD S. JOHN R. STARK, Executive Director LOUGHLIN F. MCHUGH, Senior Economist RICHARD F. KAUFMAN, General Counsel ECONOMISTS SARAH JACKSON WILLIAM A. Cox LuCY A. FALCONE JOHN R. KARLIK L. DOUGLAS LEE JERRY J. JASINOWSKI YUSPEH COURTENAY M. SLATER LARRY MINORITY (Counsel) WALTER B. LAESSIG (Counsel) LESLIE J. BANDER GEORGE D. KRUMBHAAR, Jr. SUBCOMMITTEE ON CONSUMER ECONOMICS HUBERT H. HUMPHREY, Minnesota, Chairman SENATE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES S. MOORHEAD, Pennsylvania WILLIAM PROXMIRE, Wisconsin WILLIAM GRIFFITHS, Michigan ABRAHAM RIBICOFF, Connecticut MARTHA W. S. REUSS, Wisconsin JACOB K. JAVITS, New York HENRY L. -

Merchants Go to Market

CHAPTER 10 Merchants Go to Market November 2009 Mary A. O’Sullivan The Wharton School University of Pennsylvania 1. INTRODUCTION The period from the late nineteenth century through the beginning of the Depression was one of dramatic change in America’s retail industry. In 1885, mass retailers – department stores, mail order firms, and chains ‐‐ were of limited importance as a share of retail sales but, by 1930, they had emerged as the most powerful players in a sector that itself had grown much larger. Traditional retailers persisted, of course, even if they accounted for a decreasing share of the retail industry, but they too made important changes in how they did business, partly in reaction to competition from mass retailers, but also in response to broader changes in their environment. Overall, this was a period of great change in American retailing even if there is debate about the economic benefits of some of the developments that occurred. Retailers were rather late arrivals on the nation’s securities markets, making an appearance only in 1901 when department stores issued securities to the public for the first time. The early issuers were department stores in pursuit of consolidation and recapitalisation. However, in the mid‐teens, major financial problems at some of the leading players soured the markets’ appetite for department store securities. Other mass retailers issued securities, in some cases to raise growth finance and in others for recapitalisation and consolidation. Overall, however, securities issues played a rather limited role in the development of the U.S. retail industry through the end of the First World War. -

Each Year, IHA Sponsors the International Home + Housewares Show

2018 State of the Industry Report The International Housewares Association – The Home Authority® – is strategically positioned to connect, inform, support and enable its international membership to lead in the global marketplace. The International Housewares Association (IHA) is committed to maximizing the success of the global home products industry on behalf of its membership by providing a world- class home products marketplace, facilitating global commerce and the buyer-seller interface, increasing consumer awareness and interest in home products, gathering and disseminating essential marketplace intelligence and educating and supporting key constituencies to improve th eir success. Each year, IHA sponsors the International Home + Housewares Show. With nearly 60,000 attendees, the Show is one of the largest trade events in the world. Future Show dates: March 2 – 5, 2019 March 14 – 17, 2020 March 13 – 16, 2021 March 5 – 8, 2022 Additional information, including registration, is available at www.housewares.org. i 2018 State of the Industry Report 2018 State of the Industry Report Dear Housewares Executive, The 2018 IHA State of the Industry Report is a joint endeavor of the International Housewares Association (IHA) and Raftery Resource Network, Inc. This publication includes a compilation of data from the IHA annual membership survey as well as data from several authoritative sources, including the U.S. Government, industry trade journals and industry data services. The timing of the report coincides with the release of key data about consumer spending during the previous year (2017). The methodology used to project housewares sales incorporates these data and remains consis7tent with prior years’ reports, with one exception, which became effective with the 2008 report.