Merchants Go to Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latinos | Creating Shopping Centers to Meet Their Needs May 23, 2014 by Anthony Pingicer

Latinos | Creating shopping centers to meet their needs May 23, 2014 by Anthony Pingicer Source: DealMakers.net One in every six Americans is Latino. Since 1980, the Latino population in the United States has increased dramatically from 14.6 million, per the Census Bureau, to exceeding 50 million today. This escalation is not just seen in major metropolitan cities and along the America-Mexico border, but throughout the country, from Cook County, Illinois to Miami-Dade, Florida. By 2050, the Latino population is projected to reach 134.8 million, resulting in a 30.2 percent share of the U.S. population. Latinos are key players in the nation’s economy. While the present economy benefits from Latinos, the future of the U.S. economy is most likely to depend on the Latino market, according to “State of the Hispanic Consumer: The Hispanic Market Imperative,” a report released by Nielsen, an advertising and global marketing research company. According to the report, the Latino buying power of $1 trillion in 2010 is predicted to see a 50 percent increase by next year, reaching close to $1.5 trillion in 2015. The U.S. Latino market is one of the top 10 economies in the world and Latino households in America that earn $50,000 or more are growing at a faster rate than total U.S. households. As for consumption trends, Latinos tend to spend more money per shopping trip and are also expected to become a powerful force in home purchasing during the next decade. Business is booming for Latinos. According to a study by the Partnership for a New Economy, the number of U.S. -

New Company to Take Over Dozens of National Stores Outposts

NEWSPAPER 2ND CLASS $2.99 VOLUME 74, NUMBER 49 NOVEMBER 30–DECEMBER 6, 2018 THE VOICE OF THE INDUSTRY FOR 73 YEARS New Company to Take Over Dozens of National Stores Outposts By Deborah Belgum Executive Editor After filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in Au- gust, National Stores has found a way to keep some of its stores open after announcing it was closing all of them. Second Avenue Capital Partners, a Schottenstein- family affiliate that is a finance company, said on Nov. 27 it closed a $20-million, asset-based credit facility to fund the purchase and ongoing working capital for a new entity called Fallas Stores. Fallas Stores will be purchasing 85 stores from National Stores during a bankruptcy-mandated auction, the company said. In October, National Stores said it was closing 184 of its stores, which operate under the nameplates Fallas, Fa- llas-Paredes, Factory 2-U and Falas in Puerto Rico. The new Fallas Stores will operate under the same model as the National Stores, selling discounted apparel and other merchandise and buying from the same vendors who sold National page 8 Black Friday Sees a Dip Over Last Year but Still Considered Strong By Andrew Asch Retail Editor While more than 165 million Americans shopped online or in stores during the Black Friday weekend—which now extends from Thanksgiving Day through Cyber Monday— the numbers were down by nearly 10 million shoppers from 2017. In 2017, some 174 million shoppers hit the malls or the Web to make purchases. This year, the National Retail Federation said the aver- age consumer spent $313.29 on gifts and holiday items dur- ing the five-day period. -

FY21 Updated YTD Expenditure Report 8.9.2021.Pdf

08/11/2021 16:43:55 FN504 MITZI RAMSEY MINIDOKA COUNTY PAGE 1 E X P E N D I T U R E A C T I V I T Y D E T A I L FISCAL YEAR 2021 FROM 10/01/2020 TO 09/30/2021 FUND 0001 GENERAL FUND (CURRENT EXPENSE) -01 CLERK / AUDITOR - - - - - - - - - - P A Y M E N T - - - - - - - - - - Acct No. Acct Description / Vendor Name Payment For Invoice No. Warrant No. Date Amount 0401-0001 SALARIES - OFFICER *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 10/09/2020 2,607.70 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 10/23/2020 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 11/06/2020 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 11/20/2020 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 12/04/2020 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 12/18/2020 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 12/31/2020 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 01/15/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 01/29/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 02/12/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 02/26/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 03/12/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 03/26/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 04/09/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 04/23/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 05/07/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 05/21/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 06/04/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 06/18/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 07/02/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 07/16/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 07/30/2021 2,625.00 *PAYROLL - EXPENSE *PAYROLL* 08/13/2021 2,625.00 60,357.70 * 0401-0002 SALARIES - DEPUTIES *PAYROLL -

CHLA 2017 Annual Report

Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Annual Report 2017 About Us The mission of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is to create hope and build healthier futures. Founded in 1901, CHLA is the top-ranked children’s hospital in California and among the top 10 in the nation, according to the prestigious U.S. News & World Report Honor Roll of children’s hospitals for 2017-18. The hospital is home to The Saban Research Institute and is one of the few freestanding pediatric hospitals where scientific inquiry is combined with clinical care devoted exclusively to children. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is a premier teaching hospital and has been affiliated with the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California since 1932. Table of Contents 2 4 6 8 A Message From the Year in Review Patient Care: Education: President and CEO ‘Unprecedented’ The Next Generation 10 12 14 16 Research: Legislative Action: Innovation: The Jimmy Figures of Speech Protecting the The CHLA Kimmel Effect Vulnerable Health Network 18 20 21 81 Donors Transforming Children’s Miracle CHLA Honor Roll Financial Summary Care: The Steven & Network Hospitals of Donors Alexandra Cohen Honor Roll of Friends Foundation 82 83 84 85 Statistical Report Community Board of Trustees Hospital Leadership Benefit Impact Annual Report 2017 | 1 This year, we continued to shine. 2 | A Message From the President and CEO A Message From the President and CEO Every year at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is by turning attention to the hospital’s patients, and characterized by extraordinary enthusiasm directed leveraging our skills in the arena of national advocacy. -

Food Distribution in the United States the Struggle Between Independents

University of Pennsylvania Law Review FOUNDED 1852 Formerly American Law Register VOL. 99 JUNE, 1951 No. 8 FOOD DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES, THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN INDEPENDENTS AND CHAINS By CARL H. FULDA t I. INTRODUCTION * The late Huey Long, contending for the enactment of a statute levying an occupation or license tax upon chain stores doing business in Louisiana, exclaimed in a speech: "I would rather have thieves and gangsters than chain stores inLouisiana." 1 In 1935, a few years later, the director of the National Association of Retail Grocers submitted a statement to the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives, I Associate Professor of Law, Rutgers University School of Law. J.U.D., 1931, Univ. of Freiburg, Germany; LL. B., 1938, Yale Univ. Member of the New York Bar, 1941. This study was originally prepared under the auspices of the Association of American Law Schools as one of a series of industry studies which the Association is sponsoring through its Committee on Auxiliary Business and Social Materials for use in courses on the antitrust laws. It has been separately published and copyrighted by the Association and is printed here by permission with some slight modifications. The study was undertaken at the suggestion of Professor Ralph F. Fuchs of Indiana University School of Law, chairman of the editorial group for the industry studies, to whom the writer is deeply indebted. His advice during the preparation of the study and his many suggestions for changes in the manuscript contributed greatly to the improvement of the text. Acknowledgments are also due to other members of the committee, particularly Professors Ralph S. -

Lehman Brothers

Lehman Brothers Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. (Pink Sheets: LEHMQ, former NYSE ticker symbol LEH) (pronounced / ˈliːm ə n/ ) was a global financial services firm which, until declaring bankruptcy in 2008, participated in business in investment banking, equity and fixed-income sales, research and trading, investment management, private equity, and private banking. It was a primary dealer in the U.S. Treasury securities market. Its primary subsidiaries included Lehman Brothers Inc., Neuberger Berman Inc., Aurora Loan Services, Inc., SIB Mortgage Corporation, Lehman Brothers Bank, FSB, Eagle Energy Partners, and the Crossroads Group. The firm's worldwide headquarters were in New York City, with regional headquarters in London and Tokyo, as well as offices located throughout the world. On September 15, 2008, the firm filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection following the massive exodus of most of its clients, drastic losses in its stock, and devaluation of its assets by credit rating agencies. The filing marked the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history.[2] The following day, the British bank Barclays announced its agreement to purchase, subject to regulatory approval, Lehman's North American investment-banking and trading divisions along with its New York headquarters building.[3][4] On September 20, 2008, a revised version of that agreement was approved by U.S. Bankruptcy Judge James M. Peck.[5] During the week of September 22, 2008, Nomura Holdings announced that it would acquire Lehman Brothers' franchise in the Asia Pacific region, including Japan, Hong Kong and Australia.[6] as well as, Lehman Brothers' investment banking and equities businesses in Europe and the Middle East. -

Department Stores on Sale: an Antitrust Quandary Mark D

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 1 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary Mark D. Bauer Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark D. Bauer, Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bauer: Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary DEPARTMENT STORES ON SALE: AN ANTITRUST QUANDARY Mark D. BauerBauer*• INTRODUCTION Department stores occupy a unique role in American society. With memories of trips to see Santa Claus, Christmas window displays, holiday parades or Fourth of July fIreworks,fireworks, department storesstores- particularly the old downtown stores-are often more likely to courthouse.' engender civic pride than a city hall building or a courthouse. I Department store companies have traditionally been among the strongest contributors to local civic charities, such as museums or symphonies. In many towns, the department store is the primary downtown activity generator and an important focus of urban renewal plans. The closing of a department store is generally considered a devastating blow to a downtown, or even to a suburban shopping mall. Many people feel connected to and vested in their hometown department store. -

Skaggs/Scaggs/Skeggs

..., I 11-69 I SKAGGS/SCAGGS/SKEGGS No attempt has been made here to establish the earliest colonial generations of this Skaggs family. Many early Skaggs lineages constructed by researchers contain inconsistencies and are missing documentation. In an attempt to match up what has been written historically with what can be factually proven there appears to be some mixing of Skaggs families and/or generations. The research presented in "Skaggs," from Early Adventures on the Western Waters by Mary B. Kegley and F. B. Kegley is factual and falls short of claiming actual familial relationships. [See extract later in this compilation.] 1 A great deal has been written about the Skaggs families and about their exploits as Long Hunters and the enormous contributions they made in opening up the trans-Appalachian areas of Kentucky and Tennessee. 2 Combining the multitude of references to these early Skaggs individuals into cohesive family units is a daunting task. The challenge is complicated by the repetitiveness of given names coupled with the lack of records resulting from the primitive nature of the wilderness in which they lived. For example in the same area of early Virginia are found references to James Skaggs, James Skaggs, Sr., James Skaggs, Jr., James (Longman) Skaggs and Little James Skaggs. 3 Besides being Long Hunters some of the Skaggs men were Baptist preachers dedicated to establishing churches and bringing the word of God into the remote wilderness settlements. 4 There are few records of births or marriages among the early Skaggs families. 5 It may be that the ministers among them conducted the ceremonies and either failed to record the events or their records did not survive. -

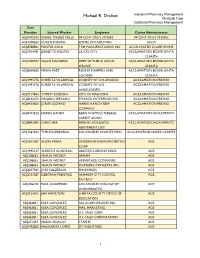

Additional Case Information

Michael R. Drobot Industrial Pharmacy Management MediLab Corp California Pharmacy Management Case Number Injured Worker Employer Claims Administrator ADJ7472102 ISMAEL TORRES VALLE 99 CENT ONLY STORES 99 CENT ONLY STORES ADJ1308567 CURTIS RIGGINS EMPIRE DISTRIBUTORS ACCA ADJ8768841 MARTIN AVILA TRM MANUFACTURING INC ACCELERATED CLAIMS IRVINE ADJ7014781 JEANETTE WILSON LA COUNTY ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA CLARITA ADJ7200937 SUSAN NAVARRO DEPT OF PUBLIC SOCIAL ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA SERVICE CLARITA ADJ8009655 MARIA PAEZ RUSKIN DAMPERS AND ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA LOUVERS CLARITA ADJ1993776 ROBERTA VILLARREAL COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ1993776 ROBERTA VILLARREAL COUNTY OF LOS ACCLAMATION FRESNO ANGELES/DPSS ADJ7117844 TOMMY ROBISON CITY OF MARICOPA ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ8162473 ONORIO SERRANO ESPARZA ENTERPRISES INC ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ8420600 JORGE LOZANO HARRIS RANCH BEEF ACCLAMATION FRESNO COMPANY ADJ8473212 DAREN HANDY KERN SCHOOLS FEDERAL ACCLAMATION SACRAMENTO CREDIT UNION ADJ8845092 CHAO HER FRESNO MOSQUITO ACCLAMATION SACRAMENTO ABATEMENT DIST ADJ1361532 THELMA JENNINGS LOS ANGELES COUNTY/DPSS ACCLAMATION SANTA CLARITA ADJ1611037 ALICIA MORA ANDERSON BARROWS METALS ACE CORP ADJ1995137 ALBERTO GUNDRAN ABLESTIK LABORATORIES ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY AMPAM ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY AMPAM RCR COMPANIES ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY PLUMBING CONCEPTS INC ACE ADJ2237965 JOSE CALDERON FMI EXPRESS ACE ADJ2353287 DEBORAH PRENTICE ANAHEIM CITY SCHOOL ACE DISTRICT ADJ246218 PAUL LIGAMMARI LOS ANGELES COLLEGE OF ACE CHIROPRACTIC -

AP Claims Time Run: 7/2/2018

AP Claims Time run: 7/2/2018 Report Parameters: Check Date - 04/01/2018,06/30/2018; Bank_Account_Name - E-PAYABLES,GENERAL,OPERATING QUARTERLY TOTAL$ 109,124,464.90 Check Check Date Vendor Name Amount Address Line1 Address Line2 City State Zip Nb662405 03‐Apr‐2018 ARIZONA PUBLIC SERVICE COMPANY $ 5,888.00 PO BOX 2907 PHOENIX AZ 85062 662406 03‐Apr‐2018 BUSTAMANTE, CARMEN (R) $ 99.00 73 S. HAMILTON #26 CHANDLER AZ 85225 662407 03‐Apr‐2018 CITY OF GLENDALE (233‐5) $ 2,644.12 HOUSING AUTHORITY 6842 N. 61ST AVE GLENDALE AZ 85301 662408 03‐Apr‐2018 CITY OF TEMPE $ 1,718.12 HOUSING/SECTION 8 HUMAN SERVICES DEPT 2ND FLOOTEMPE AZ 85282 662409 03‐Apr‐2018 COLORES, JUAN $ 200.00 130 N HAMILTON #43 CHANDLER AZ 85225 662410 03‐Apr‐2018 DUPAGE HOUSING AUTHORITY $ 1,423.04 711 E ROOSEVELT WHEATON IL 60187 662411 03‐Apr‐2018 FLAGSTAFF HOUSING AUTHORITY $ 886.04 PO BOX 2098 FLAGSTAFF AZ 86003 662412 03‐Apr‐2018 FOLEY HOUSING AUTHORITY $ 1,375.04 302 4TH AVE FOLEY AL 36535 662413 03‐Apr‐2018 HOUSING AUTHORITY OF THE CITY OF TAMPA $ 664.04 5301 W CYPRESS ST TAMPA FL 33607 662414 03‐Apr‐2018 HOUSING AUTHORITY OF THE CITY OF YUMA $ 162.04 420 S MADISON AVENUE YUMA AZ 85634 662415 03‐Apr‐2018 HOUSING AUTHORITY OF THE COUNTY OF ALAMEDA $ 1,600.04 22941 ATHERTON ST HAYWARD CA 94541 662416 03‐Apr‐2018 HUERTA, JUANITA $ 110.00 660 S PALM LN, #27 CHANDLER AZ 85224 662417 03‐Apr‐2018 KING COUNTY HOUSING AUTHORITY $ 8,341.24 600 ANDOVER PARK WEST SEATTLE WASHIN 98188‐2583 662418 03‐Apr‐2018 LA TEMPA, ANDREA (R) $ 32,749.27 2272 E REMINGTON PL CHANDLER AZ 85286 662419 03‐Apr‐2018 MARICOPA COUNTY HOUSING AUTHORITY $ 3,345.12 8910 N 78TH AVE BLDG D PEORIA AZ 85345 662420 03‐Apr‐2018 MARTINEZ, LETICIA (R) $ 26.00 210 N MCQUEEN #17 CHANDLER AZ 85225 662421 03‐Apr‐2018 OGAS, MARIA (R) $ 153.00 130 N HAMILTON #25 CHANDLER AZ 85225 662422 03‐Apr‐2018 ORANGE COUNTY HOUSING AUTHORITY $ 2,489.08 1770 N BROADWAY SANTA ANA CA 92706 662423 03‐Apr‐2018 ORELLANA, LESLIE (R) $ 37.00 130 N. -

General Background

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Earth and Mineral Sciences RESTRUCTURING DEPARTMENT STORE GEOGRAPHIES: THE LEGACIES OF EXPANSION AND CONSOLIDATION IN PHILADELPHIA’S JOHN WANAMAKER AND STRAWBRIDGE & CLOTHIER, 1860-1960 A Thesis in Geography by Wesley J Stroh © 2008 Wesley J Stroh Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2008 The thesis of Wesley J. Stroh was reviewed and approved* by the following: Deryck W. Holdsworth Professor of Geography Thesis Adviser Roger M. Downs Professor of Geography Karl Zimmerer Professor of Geography Head of the Department of Geography *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ABSTRACT RESTRUCTURING DEPARTMENT STORE GEOGRAPHIES: THE LEGACIES OF EXPANSION AND CONSOLIDATION IN PHILADELPHIA’S JOHN WANAMAKER AND STRAWBRIDGE & CLOTHIER, 1860-1960 Consolidation in the retail sector continues to restructure the department store, and the legacies of earlier forms of the department store laid the foundation for this consolidation. Using John Wanamaker’s and Strawbridge & Clothier, antecedents of Macy’s stores in Philadelphia, I undertake a case study of the development, through expansion and consolidation, which led to a homogenized department store retail market in the Philadelphia region. I employ archival materials, biographies and histories, and annual reports to document and characterize the development and restructuring Philadelphia’s department stores during three distinct phases: early expansions, the first consolidations into national corporations, and expansion through branch stores and into suburban shopping malls. In closing, I characterize the processes and structural legacies which department stores inherited by the latter half of the 20th century, as these legacies are foundational to national-scale retail homogenization. -

Robert Lehman Papers

Robert Lehman papers Finding aid prepared by Larry Weimer The Robert Lehman Collection Archival Project was generously funded by the Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc. This finding aid was generated using Archivists' Toolkit on September 24, 2014 Robert Lehman Collection The Metropolitan Museum of Art 1000 Fifth Avenue New York, NY, 10028 [email protected] Robert Lehman papers Table of Contents Summary Information .......................................................................................................3 Biographical/Historical note................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents note...................................................................................................34 Arrangement note.............................................................................................................. 36 Administrative Information ............................................................................................ 37 Related Materials ............................................................................................................ 39 Controlled Access Headings............................................................................................. 41 Bibliography...................................................................................................................... 40 Collection Inventory..........................................................................................................43 Series I. General