Thalhimers Department Store: Story, History, and Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jational Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

•m No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE JATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS >_____ NAME HISTORIC BROADWAY THEATER AND COMMERCIAL DISTRICT________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER <f' 300-8^9 ^tttff Broadway —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles VICINITY OF 25 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Los Angeles 037 | CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED .^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE .XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^ENTERTAINMENT _ REUGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS 2L.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: NAME Multiple Ownership (see list) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF | LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Los Angeie s County Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 320 West Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles California ! REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE California Historic Resources Inventory DATE July 1977 —FEDERAL ^JSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS office of Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE . ,. Los Angeles California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD 0 —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Broadway Theater and Commercial District is a six-block complex of predominately commercial and entertainment structures done in a variety of architectural styles. The district extends along both sides of Broadway from Third to Ninth Streets and exhibits a number of structures in varying condition and degree of alteration. -

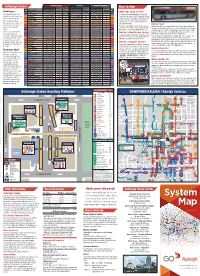

System Every Bus That Travels Through Downtown Stops at One-Way Fare

MONDAY–FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY / HOLIDAYS GoRaleigh Routes SPAN FREQUENCY (Minutes) SPAN FREQUENCY SPAN FREQUENCY How To Ride RT # ROUTE NAME (Operating hours) Peak Off-Peak (Operating hours) (Minutes) (Operating hours) (Minutes) RT # Route Types 1 Capital 4:30am–12:10am 15 15 or 60 5:45am–12:08am 30 or 60 5:45am–11:27pm 30 or 60 1 Where do I catch the bus? Most GoRaleigh routes are 2 Falls of Neuse 5:00am–11:25pm 30 30 or 60 5:30am–10:59pm 60 5:30am–10:59pm 60 2 You can catch a GoRaleigh bus at one of the radial routes which begin and 3 Glascock 6:15am–9:44pm 30 60 7:00am–8:42pm 60 7:00am–8:42pm 60 3 many bus stop signs located throughout Raleigh. end in downtown Raleigh. 4 Rex Hospital 4:30am–12:15am 30 30 4:30am–12:15am 30 4:30am–12:15am 30 4 These signs are conveniently located along each 5 Biltmore Hills 5:30am–12:03am 30 60 6:10am–12:12am 60 6:10am–11:12pm 60 5 route. (Please be at your stop a few minutes The “L” routes circulate early–the bus is expected within 5 minutes of 6 Crabtree 5:55am–9:15pm 30 60 7:00am–10:00pm 60 7:00am–10:00pm 60 6 through an area or operate as the scheduled time.) a cross-town route and link 7 South Saunders 5:45am–11:45pm 15 15 or 60 6:00am–11:45pm 30 or 60 6:00am–10:59pm 30 or 60 7 How do I pay? For issues regarding bus stops/shelters, please with one or more radial 7L Carolina Pines 5:45am–11:00pm 30 60 6:45am–9:33pm 60 6:45am–9:33pm 60 7L All GoRaleigh buses are equipped with electronic fareboxes. -

For Controversial NAS, All's Quiet on the National Front

WELCOME BACK ALUMNI •:- •:• -•:•••. ;:: Holy war THE CHRONICLE theo FRIDAY. NOVEMBER 2, 1990 DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA Huge pool of candidates Budget crunch threatens jazz institute leaves Pearcy concerned Monk center on hold for now r- ————. By JULIE MEWHORT From staff reports Ronald Krifcher, Brian Ladd, performing and non-performing An exceptionally large can David Rollins and Steven The creation ofthe world's first classes in jazz. didate pool for the ASDU Wild, Trinity juniors Sam conservatory for jazz music is on The Durham city and county presidency has President Con Bell, Marc Braswell, Mandeep hold for now. governments have already pur nie Pearcy skeptical of the in Dhillon, Eric Feddern, Greg During the budgeting process chased land for the institute at tentions of several of the can Holcombe, Kirk Leibert, Rich this summer, the North Carolina the intersection of Foster and didates. Pierce, Tonya Robinson, Ran General Assembly was forced to Morgan streets, but officials do Twenty-five people com dall Skrabonja and Heyward cut funding for an indefinite not have funds to begin actual pleted declaration forms Wall, Engineering juniors period to the Thelonious Monk construction. before yesterday's deadline. Chris Hunt and Howard Institute. "Our response is to recognize Last year only four students Mora, Trinity sophomores The institute, a Washington- that the state has several finan ran for the office. James Angelo, Richard Brad based organization, has been cial problems right now. We just Pearcy said she and other ley, Colin Curvey, Rich Sand planning to build a music conser have to continue hoping that the members of the Executive ers and Jeffrey Skinner and vatory honoring in downtown budget will improve," said Committee are trying to de Engineering sophomores Durham. -

Aiche Chicago Section October Newsletter

AIChE Chicago Section October Newsletter Chicago Section www.aiche-chicago.org October 2012 AIChE Chicago October 2012 Meeting Notice Blind Spots: The 10 Business Myths You Can’t Afford to Believe on Your New Path to Success, Inside this issue: By: Alexandra Levit 2 Chair’s Corner Business & Workplace Author, October Meeting Info 3 Speaker, and Consultant AIChE Live Webinars 4 Upcoming Meetings 5 Date: Wednesday, October 10th, 2012 AIChE Midwest Re- 5 gional Conference Location: La Tasca Tapas Restaurant 25 W. Davis Street, Arlington Heights, IL 60005 Young Professionals 5 Ten Signs of jog dissat- 7 Cost: Members: $35 Non-Members: $40 isfaction C2ST Meeting Informa- 8 Students: $5 Unemployed Members: $20 tion To Register Click the Link; http://www.cvent.com/d/tcqx2l/4W What is New 9 Thiele Award 9 Agenda High School Program at 10 Meeting registration 5:30 pm 2013 MWRC Alexandra’s Pre-Meeting Event: How 6:00—6:45 pm to start a Successful Career Dinner 6:45 - 7:30 pm Section business 7:30 - 7:45 pm Speaker 7:45 - 8:45 pm Meeting close 8:45 pm PAGE 2 OCTOBER NEWSLETTER CHICAGO SECTION Chair’s Corner Being an asset to the organization for which yourself, a friend or you work first means understanding how to family member. A dona- plan your career smartly. Adopting tactics in tion option is on the the business environment that are beneficial to monthly meeting regis- the individual, but threaten workplace effi- tration page. For more ciency, is taking a path that can lead to either information on the personal dissatisfaction or career strangula- scholarship program tion. -

Target Corporation

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program Spring 4-7-2019 Strategic Audit: Target Corporation Andee Capell University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Strategic Management Policy Commons Capell, Andee, "Strategic Audit: Target Corporation" (2019). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska- Lincoln. 192. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Strategic Audit: Target Corporation An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial fulfillment of University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska-Lincoln by Andee Capell, BS Accounting College of Business April 7th, 2019 Faculty Mentor: Samuel Nelson, PhD, Management Abstract Target Corporation is a notable publicly traded discount retailer in the United States. In recent years they have gone through significant changes including a new CEO Brian Cornell and the closing of their Canadian stores. With change comes a new strategy, which includes growing stores in the United States. In order to be able to continue to grow Target should consider multiple strategic options. Using internal and external analysis, while examining Target’s profitability ratios recommendations were made to proceed with their growth both in profit and capacity. After recommendations are made implementation and contingency plans can be made. Key words: Strategy, Target, Ratio(s), Plan 1 Table of Contents Section Page(s) Background information …………………..…………………………………………….…..…...3 External Analysis ………………..……………………………………………………..............3-5 a. -

Finding Thalhimers Online

HUQBt (Download) Finding Thalhimers Online [HUQBt.ebook] Finding Thalhimers Pdf Free Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1290300 in Books Dementi Milestone Publishing 2010-10-16Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 10.14 x 1.17 x 7.30l, 2.08 #File Name: 0982701918274 pages | File size: 71.Mb Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt : Finding Thalhimers before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Finding Thalhimers: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Indepth Look at an American Success StoryBy Jennifer L. SetterstromI thought I was getting a book about the history of Thalhimers,a department store in Richmond Virginia, but it is so much more! Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt has done a superb job in tracing her family roots all the way back to the first Thalhimer who came to America from Germany to eventually begin a business that would grow and expand and endure for decades. I grew up with Thalhimers, so this was particularly interesting to me. The book covers not only a long lineage of Thalihimer business men(and their families) but gives the reader a good look at Richmond history. How the final demise of such an iconic part of Richmond came to be is a reflection of the fate of most of the department stores we baby boomers grew up with. A satisfying read with a touch of nostalgia, and truly a through well told story of the American dream.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. -

Macys Janelle Godfrey.Pdf

M a c y ’ s Introduce - Macy's, Inc., originally Federated Department Stores, Inc., is an American holding company headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio. It is the owner of department store chains Macy's and Bloomingdale's, which specialize in the sales of clothing, footwear, accessories, bedding, furniture, jewelry, beauty products, and housewares; and Bluemercury, a chain of luxury beauty products stores and spas. As of 2016, the company operated approximately 888 stores in the United States, Guam, and Puerto Rico Its namesake locations and related operations account for 90% of its revenue. - - Macy's was founded by Rowland Hussey Macy, who between 1843 and 1855 opened four retail dry goods stores, including the original Macy's store in downtown Haverhill, Massachusetts, established in 1851 to serve the mill industry employees of the area. They all failed, but he learned from his mistakes. Macy moved to New York City in 1858 and established a new store named "R. H. Macy & Co." on Sixth Avenue between 13th and 14th Streets, which was far north of where other dry goods stores were at the time On the company's first day of business on October 28, 1858 sales totaled US$11.08, equal to $306.79 today. From the beginning, Macy's logo has included a star, which comes from a tattoo that Macy got as a teenager when he worked on a Nantucket whaling ship, the Emily Morgan Introduce - As the business grew, Macy's expanded into neighboring buildings, opening more and more departments, and used publicity devices such as a store Santa Claus, themed exhibits, and illuminated window displays to draw in customers. -

La Salle Magazine Spring 1982 La Salle University

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons La Salle Magazine University Publications Spring 1982 La Salle Magazine Spring 1982 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/lasalle_magazine Recommended Citation La Salle University, "La Salle Magazine Spring 1982" (1982). La Salle Magazine. 104. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/lasalle_magazine/104 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in La Salle Magazine by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spring 1982 A QUARTERLY LA SALLE COLLEGE MAGAZINE The Litigator Attorney James J. Binns Volume 26 Spring 1982 Number 2 Robert S. Lyons, Jr., '61, Editor James J. McDonald, '58, Alumni Director Mary Beth Bryers, '76, Editor, Class Notes ALUMNI ASSOCIATION OFFICERS John J. Fallon, '67, President Philip E. Hughes, Jr., Esq., '71, Executive V.P. A QUARTERLY LASALLE COLLEGE MAGAZINE Donald Rongione, '79, Vice President Anthony W. Martin, '74, Secretary (USPS 299-940) Paul J. Kelly, '78, Treasurer Contents 1 THE FINANCIAL AID CRISIS Projected cuts suggested by the Reagan Ad ministration would have a devastating effect on La Salle’s student body. 6 THE LITIGATOR Jim Binns loves the action in the courtroom where he has represented some of the nation’s biggest corporate, congressional, and com petitive names. Jim Binns and the Governor, Page 6 9 A ROAD MAP FOR FAMILY SECURITY exts of the Douai-Rheims Tax Attorney Terence K. Heaney discusses the are, for the most part, di necessity of comprehensive estate planning. -

Future of Millennial Careers White Paper

How the Recession Shaped Millennial and Hiring Manager Attitudes about Millennials’ Future Careers By Alexandra Levit with Dr. Sanja Licina Commissioned by the Career Advisory Board How the Recession Shaped Millennial and Hiring Manager Attitudes about Millennials’ Future Careers TABLE OF CONTENTS CAREER ADVISORY BOARD Summary .................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................ 4 Claude Toland Chairman Who’s Who in Today’s Workplace ............................. 5 An Evolution in Progress ........................................... 6 Vito Amato Jesus Fernandez Study Overview .......................................................... 8 Pete Joodi Pursuing Advanced Education ................................... 10 Dan Kasun Changing Career and Work Situations ....................... 14 Kristin Machacek Leary Surmounting Unique Challenges ............................... 22 Alexandra Levit Identifying, Addressing Millennial Weaknesses ........ 25 Dr. Sanja Licina About the Career Advisory Board, Methodology ...... 29 Erica Orange Meet the Authors ........................................................ 31 Jason Seiden References .................................................................. 33 2 ©2011, Career Advisory Board Reproduction Prohibited How the Recession Shaped Millennial and Hiring Manager Attitudes about Millennials’ Future Careers SUMMARY any believe the recession is on its way out. According to the Bureau Mof Labor Statistics, -

Capital Boulevard North Community Profile Report

median home value $150k #1 transit route by ridership 300+ private businesses 80k vehicle trips per day Table of Contents Introduction 4 Boundaries and Demographics 7 Vehicular Transportation 15 Pedestrians, Bicycles and Transit 22 Land Use and Built Environment 28 Parks and Natural Environment 30 Segment Analysis 32 Appendices A. Maps B. Existing Transportation Plans C. Market Analysis D. Mobile Tour 3 Capital Boulevard North CBN Community Profile Introduction An area of influence has been defined that includes Purpose of the residential neighborhoods that lie just outside the study area. These communities might not be the Community Profile subject of recommendations from the study, but will The Community Profile gives a description of the likely experience effects from changes along Capital area that may be affected by the recommendations Boulevard. of the Capital Boulevard North Corridor Study. This Capital Boulevard is a main thoroughfare for area includes the length of Capital Boulevard from personal vehicle and bus trips between Downtown I-440 to I-540 as well as nearby properties to the Raleigh, I-440, and I-540. The portion of Capital east and west. Before creating ideas for the future of Boulevard in the study carries a large volume of the corridor, it is important to understand what it is local and regional travellers. Its busiest section like in the present. Information about the current moves 80,000 car trips per day. The local bus route conditions in the area is also useful for deciding what that runs the length of the study area, GoRaleigh topics to research and analyze and how those topics Route 1, provided approximately 5,000 passenger relate to one another. -

Department Stores on Sale: an Antitrust Quandary Mark D

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 1 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary Mark D. Bauer Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark D. Bauer, Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bauer: Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary DEPARTMENT STORES ON SALE: AN ANTITRUST QUANDARY Mark D. BauerBauer*• INTRODUCTION Department stores occupy a unique role in American society. With memories of trips to see Santa Claus, Christmas window displays, holiday parades or Fourth of July fIreworks,fireworks, department storesstores- particularly the old downtown stores-are often more likely to courthouse.' engender civic pride than a city hall building or a courthouse. I Department store companies have traditionally been among the strongest contributors to local civic charities, such as museums or symphonies. In many towns, the department store is the primary downtown activity generator and an important focus of urban renewal plans. The closing of a department store is generally considered a devastating blow to a downtown, or even to a suburban shopping mall. Many people feel connected to and vested in their hometown department store. -

The Bon-Ton Stores, Inc. Announces Locations of Store Closures As Part of Store Rationalization Program

The Bon-Ton Stores, Inc. Announces Locations of Store Closures as Part of Store Rationalization Program January 31, 2018 MILWAUKEE, Jan. 31, 2018 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- The Bon-Ton Stores, Inc. (OTCQX:BONT) ("the Company"), today announced the 42 locations that will be closed as part of its previously communicated store rationalization program. The closing stores will include locations under all of the Company's nameplates. "As part of the comprehensive turnaround plan we announced in November, we are taking the next steps in our efforts to move forward with a more productive store footprint," said Bill Tracy, president and chief executive officer for The Bon-Ton Stores. "Including other recently announced store closures, we expect to close a total of 47 stores in early 2018. We remain focused on executing our key initiatives to drive improved performance in an effort to strengthen our capital structure to support the business going forward." Mr. Tracy continued, "We would like to thank the loyal customers who have shopped at these locations and express deep gratitude to our team of hard-working associates for their commitment to Bon-Ton and to serving our customers." In order to ensure a seamless experience for customers, Bon-Ton has partnered with a third-party liquidator, Hilco Merchant Resources, to help manage the store closing sales. The store closing sales are scheduled to begin on February 1, 2018 and run for approximately 10 to 12 weeks. Associates at these locations will be offered the opportunity to interview for available positions at other store locations. The closing locations announced today are in addition to five other recently announced store closures, four of which the Company completed at the end of January and one at which the Company will conclude its closing sale in February.