Download a Sample

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alif and Hamza Alif) Is One of the Simplest Letters of the Alphabet

’alif and hamza alif) is one of the simplest letters of the alphabet. Its isolated form is simply a vertical’) ﺍ stroke, written from top to bottom. In its final position it is written as the same vertical stroke, but joined at the base to the preceding letter. Because of this connecting line – and this is very important – it is written from bottom to top instead of top to bottom. Practise these to get the feel of the direction of the stroke. The letter 'alif is one of a number of non-connecting letters. This means that it is never connected to the letter that comes after it. Non-connecting letters therefore have no initial or medial forms. They can appear in only two ways: isolated or final, meaning connected to the preceding letter. Reminder about pronunciation The letter 'alif represents the long vowel aa. Usually this vowel sounds like a lengthened version of the a in pat. In some positions, however (we will explain this later), it sounds more like the a in father. One of the most important functions of 'alif is not as an independent sound but as the You can look back at what we said about .(ﺀ) carrier, or a ‘bearer’, of another letter: hamza hamza. Later we will discuss hamza in more detail. Here we will go through one of the most common uses of hamza: its combination with 'alif at the beginning or a word. One of the rules of the Arabic language is that no word can begin with a vowel. Many Arabic words may sound to the beginner as though they start with a vowel, but in fact they begin with a glottal stop: that little catch in the voice that is represented by hamza. -

Arabic Alphabet - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Arabic Alphabet from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

2/14/13 Arabic alphabet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Arabic alphabet From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia َأﺑْ َﺠ ِﺪﯾﱠﺔ َﻋ َﺮﺑِﯿﱠﺔ :The Arabic alphabet (Arabic ’abjadiyyah ‘arabiyyah) or Arabic abjad is Arabic abjad the Arabic script as it is codified for writing the Arabic language. It is written from right to left, in a cursive style, and includes 28 letters. Because letters usually[1] stand for consonants, it is classified as an abjad. Type Abjad Languages Arabic Time 400 to the present period Parent Proto-Sinaitic systems Phoenician Aramaic Syriac Nabataean Arabic abjad Child N'Ko alphabet systems ISO 15924 Arab, 160 Direction Right-to-left Unicode Arabic alias Unicode U+0600 to U+06FF range (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0600.pdf) U+0750 to U+077F (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0750.pdf) U+08A0 to U+08FF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U08A0.pdf) U+FB50 to U+FDFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UFB50.pdf) U+FE70 to U+FEFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UFE70.pdf) U+1EE00 to U+1EEFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1EE00.pdf) Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols. Arabic alphabet ا ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arabic_alphabet 1/20 2/14/13 Arabic alphabet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia غ ف ق ك ل م ن ه و ي History · Transliteration ء Diacritics · Hamza Numerals · Numeration V · T · E (//en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Template:Arabic_alphabet&action=edit) Contents 1 Consonants 1.1 Alphabetical order 1.2 Letter forms 1.2.1 Table of basic letters 1.2.2 Further notes -

DRAFT Arabtex a System for Typesetting Arabic User Manual Version 4.00

DRAFT ArabTEX a System for Typesetting Arabic User Manual Version 4.00 12 Klaus Lagally May 25, 1999 1Report Nr. 1998/09, Universit¨at Stuttgart, Fakult¨at Informatik, Breitwiesenstraße 20–22, 70565 Stuttgart, Germany 2This Report supersedes Reports Nr. 1992/06 and 1993/11 Overview ArabTEX is a package extending the capabilities of TEX/LATEX to generate the Perso-Arabic writing from an ASCII transliteration for texts in several languages using the Arabic script. It consists of a TEX macro package and an Arabic font in several sizes, presently only available in the Naskhi style. ArabTEX will run with Plain TEXandalsowithLATEX2e. It is compatible with Babel, CJK, the EDMAC package, and PicTEX (with some restrictions); other additions to TEX have not been tried. ArabTEX is primarily intended for generating the Arabic writing, but the stan- dard scientific transliteration can also be easily produced. For languages other than Arabic that are customarily written in extensions of the Perso-Arabic script some limited support is available. ArabTEX defines its own input notation which is both machine, and human, readable, and suited for electronic transmission and E-Mail communication. However, texts in many of the Arabic standard encodings can also be processed. Starting with Version 3.02, ArabTEX also provides support for fully vowelized Hebrew, both in its private ASCII input notation and in several other popular encodings. ArabTEX is copyrighted, but free use for scientific, experimental and other strictly private, noncommercial purposes is granted. Offprints of scientific publi- cations using ArabTEX are welcome. Using ArabTEX otherwise requires a license agreement. There is no warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. -

Word Stress and Vowel Neutralization in Modern Standard Arabic

Word Stress and Vowel Neutralization in Modern Standard Arabic Jack Halpern (春遍雀來) The CJK Dictionary Institute (日中韓辭典研究所) 34-14, 2-chome, Tohoku, Niiza-shi, Saitama 352-0001, Japan [email protected] rules differ somewhat from those used in liturgi- Abstract cal Arabic. Word stress in Modern Standard Arabic is of Arabic word stress and vowel neutralization great importance to language learners, while rules have been the object of various studies, precise stress rules can help enhance Arabic such as Janssens (1972), Mitchell (1990) and speech technology applications. Though Ara- Ryding (2005). Though some grammar books bic word stress and vowel neutralization rules offer stress rules that appear short and simple, have been the object of various studies, the lit- erature is sometimes inaccurate or contradic- upon careful examination they turn out to be in- tory. Most Arabic grammar books give stress complete, ambiguous or inaccurate. Moreover, rules that are inadequate or incomplete, while the linguistic literature often contains inaccura- vowel neutralization is hardly mentioned. The cies, partially because little or no distinction is aim of this paper is to present stress and neu- made between MSA and liturgical Arabic, or tralization rules that are both linguistically ac- because the rules are based on Egyptian-accented curate and pedagogically useful based on how MSA (Mitchell, 1990), which differs from stan- spoken MSA is actually pronounced. dard MSA in important ways. 1 Introduction Arabic stress and neutralization rules are wor- Word stress in both Modern Standard Arabic thy of serious investigation. Other than being of (MSA) and the dialects is non-phonemic. -

Mpub10110094.Pdf

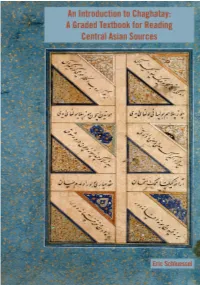

An Introduction to Chaghatay: A Graded Textbook for Reading Central Asian Sources Eric Schluessel Copyright © 2018 by Eric Schluessel Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. Published in the United States of America by Michigan Publishing Manufactured in the United States of America DOI: 10.3998/mpub.10110094 ISBN 978-1-60785-495-1 (paper) ISBN 978-1-60785-496-8 (e-book) An imprint of Michigan Publishing, Maize Books serves the publishing needs of the University of Michigan community by making high-quality scholarship widely available in print and online. It represents a new model for authors seeking to share their work within and beyond the academy, offering streamlined selection, production, and distribution processes. Maize Books is intended as a complement to more formal modes of publication in a wide range of disciplinary areas. http://www.maizebooks.org Cover Illustration: "Islamic Calligraphy in the Nasta`liq style." (Credit: Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/chengwfg/, licensed under CC BY 4.0) Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction vi How to Read the Alphabet xi 1 Basic Word Order and Copular Sentences 1 2 Existence 6 3 Plural, Palatal Harmony, and Case Endings 12 4 People and Questions 20 5 The Present-Future Tense 27 6 Possessive -

Accordance Fonts(November 2010)

Accordance Fonts (November 2010) Contents Installing the Fonts . 2. OS X Font Display in Accordance and above . 2. Font Display in Other OS X Applications . 3. Converting to Unicode . 4. Other Font Tips . 4. Helena Greek Font . 5. Additional Character Positions for Helena . 5. Helena Greek Font . 6. Yehudit Hebrew Font . 7. Table of Hebrew Vowels and Other Characters . 7. Yehudit Hebrew Font . 8. Notes on Yehudit Keyboard . 9. Table of Diacritical Characters(not used in the Hebrew Bible) . 9. Table of Accents (Cantillation Marks, Te‘amim) — see notes at end . 9. Notes on the Accent Table . 1. 2 Peshitta Syriac Font . 1. 3 Characters in non-standard positions . 1. 3 Peshitta Syriac Font . 1. 4 Syriac vowels, other diacriticals, and punctuation: . 1. 5 Rosetta Transliteration Font . 1. 6 Character Positions for Rosetta: . 1. 6 Sylvanus Uncial/Coptic Font . 1. 8 Sylvanus Uncial Font . 1. 9 MSS Font for Manuscript Citation . 2. 1 MSS Manuscript Font . 2. 2 Salaam Arabic Font . 2. 4 Characters in non-standard positions . 2. 4 Salaam Arabic Font . 2. 5 Arabic vowels and other diacriticals: . 2. 6 Page 1 Accordance Fonts OS X font Seven fonts are supplied for use with Accordance: Helena for Greek, Yehudit for Hebrew, Peshitta for Syriac, Rosetta for files transliteration characters, Sylvanus for uncial manuscripts, and Salaam for Arabic . An additional MSS font is used for manuscript citations . Once installed, the fonts are also available to any other program such as a word processor . These fonts each include special accents and other characters which occur in various overstrike positions for different characters . -

Classifying Arabic Fonts Based on Design Characteristics: PANOSE-A

Classifying Arabic Fonts Based on Design Characteristics: PANOSE-A Jehan Janbi A Thesis In the Department of Computer Science & Software Engineering Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Computer Science) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada July 2016 © Jehan Janbi, 2016 Abstract In desktop publishing, fonts are essential components in each document design. With the development of font design software and tools, there are thousands of digital fonts. Increasing the number of available fonts makes selecting an appropriate font, which best serves the objective of a design, not an intuitive issue. Designers can search for a font like any other file types by using general information such as name and file format. But for document design purposes, the design features or visual characteristics of fonts are more meaningful for designers than font file information. Therefore, representing fonts’ design features by searchable and comparable data would facilitate searching and selecting a desirable font. One solution is to represent a font’s design features by a code composed of several digits. This solution has been implemented as a computerized system called PANOSE-1 for Latin script fonts. PANOSE-1 is a system for classifying and matching typefaces based on design features. It is composed of 10 digits, where each digit represents a specific design feature. It is used within several font management tools as an option for ordering and searching fonts based on their design features. It is also used in font replacement processes when an application or an operating system detects a missing font in an immigrant document or website. -

The Secret of Letters: Chronograms in Urdu Literary Culture1

Edebiyˆat, 2003, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 147–158 The Secret of Letters: Chronograms in Urdu Literary Culture1 Mehr Afshan Farooqi University of Virginia Letters of the alphabet are more than symbols on a page. They provide an opening into new creative possibilities, new levels of understanding, and new worlds of experience. In mature literary traditions, the “literal meaning” of literal meaning can encompass a variety of arcane uses of letters, both in their mode as a graphemic entity and as a phonemic activity. Letters carry hidden meanings in literary languages at once assigned and intrinsic: the numeric and prophetic, the cryptic and esoteric, and the historic and commemoratory. In most literary traditions there appears to be at least a threefold value system assigned to letters: letters can be seen as phonetic signs, they have a semantic value, and they also have a numerical value. Each of the 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet can be used as a numeral. When used numerically, the letters of the alphabet have a special order, which is called the abjad or abujad. Abjad is an acronym referring to alif, be, j¯ım, d¯al, the first four letters in the numerical order which, in the system most widely used, runs from alif to ghain. The abjad order organizes the 28 characters of the Arabic alphabet into eight groups in a linear series: abjad, havvaz, hutt¯ı, kalaman, sa`fas, qarashat, sakhkha˙˙ z, zazzagh.2 In nearly every area where˙ ¨the¨ Arabic script ˙ was adopted, the abjad¨ ˙ ˙system gained popularity. Within the vast area in which the Arabic script was used, two abjad systems developed. -

Modern Standard Arabic 3

® Modern Standard Arabic 3 “I have completed the entire Pimsleur Spanish series. I have always wanted to learn, but failed on numerous occasions. Shockingly, this method worked beautifully. ” R. Rydzewsk (Burlington, NC) “The thing is, Pimsleur is PHENOMENALLY EFFICIENT at advancing your oral skills wherever you are, and you don’t have to make an appointment or be at your computer or deal with other students. ” Ellen Jovin (NY, NY) “I looked at a number of different online and self-taught courses before settling on the Pimsleur courses. I could not have made a better choice. ” M. Jaffe (Mesa, AZ) Modern Standard Arabic 3 Travelers should always check with their nation's State Department for current advisories on local conditions before traveling abroad. Booklet Design: Maia Kennedy © and ‰ Recorded Program 2015 Simon & Schuster, Inc. © Reading Booklet 2015 Simon & Schuster, Inc. Pimsleur® is an imprint of Simon & Schuster Audio, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Mfg. in USA. All rights reserved. ii Modern Standard Arabic 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS VOICES English-Speaking Instructor . Ray Brown Arabic-Speaking Instructor. Husam Karzoun Female Arabic Speaker . Maya Asmar Male Arabic Speaker . .Bayhas Kana COURSE WRITERS Dr. Mahdi Alosh ♦ Shannon Rossi EDITORS Beverly D. Heinle ♦ Mary E. Green REVIEWERS Ibtisam Alama ♦ Duha Shamaileh Bayhas Kana PRODUCER Sarah H. McInnis RECORDING ENGINEER Peter S. Turpin Simon & Schuster Studios, Concord, MA iii Modern Standard Arabic 3 Table of Contents Introduction. 1 The Arabic Alphabet . 3 Reading Lessons . 7 Arabic Alphabet Chart . 8 Diacritical Marks . 10 Lesson One . 11 Lesson Two . 14 Lesson Three . 17 Lesson Four . 20 Lesson Five . -

Middle East-I 9 Modern and Liturgical Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

The Challenges and Pitfalls of Arabic Romanization and Arabization

The Challenges and Pitfalls of Arabic Romanization and Arabization Jack Halpern (春遍雀來) The CJK Dictionary Institute, Inc. (日中韓辭典研究所) 34-14, 2-chome, Tohoku, Niiza-shi, Saitama 352-0001, Japan [email protected] their native script directly into Arabic, something Abstract probably never attempted. These systems are part of our ongoing efforts to develop Arabic re- The high level of ambiguity of the Ara- sources for automatic transcription, machine bic script poses special challenges to translation and named entity extraction. developers of NLP tools in areas such as morphological analysis, named entity The following typographic conventions are used extraction and machine translation. in this paper: These difficulties are exacerbated by the lack of comprehensive lexical resources, 1. Phonemic transcriptions are indicated by . (/qaabuus/ < ﻗــــﺎﺑﻮس) such as proper noun databases, and the slashes multiplicity of ambiguous transcription 2. Phonetic transcriptions are indicated by . ([qɑːbuːs] < ﻗــــﺎﺑﻮس ) schemes. This paper focuses on some of square brackets the linguistic issues encountered in two subdisciplines that play an increasingly 3. Graphemic transliterations are indicated by . (\qAbws\ < ﻗــــﺎﺑﻮس ) important role in Arabic information back slashes processing: the romanization of Arabic 4. Popular transcriptions are indicated by italics .(Qaboos < ﻗــــﺎﺑﻮس ) -names and the arabization of non Arabic names. The basic premise is that linguistic knowledge in the form of lin- 2 Motivation and Previous Work guistic rules is essential for achieving Arabic transcription technology is playing an high accuracy. increasingly important role in a variety of practical applications such as named entity 1 Introduction recognition, machine translation, cross-language information retrieval and various security The process of automatically transcribing Arabic applications such as anti-money laundering and to a Roman script representation, called romani- terrorist watch lists. -

Reading Booklet Modern Standard Arabic 1

® Modern Standard Arabic 1 Reading Booklet Modern Standard Arabic 1 Travelers should always check with their nation's State Department for current advisories on local conditions before traveling abroad. Booklet Design: Maia Kennedy © and ‰ Recorded Program 2012 Simon & Schuster, Inc. © Reading Booklet 2012 Simon & Schuster, Inc. Pimsleur® is an imprint of Simon & Schuster Audio, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Mfg. in USA. All rights reserved. ii Modern Standard Arabic 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS VOICES English-Speaking Instructor . Ray Brown Arabic-Speaking Instructor. Alex Tamer Female Arabic Speaker . Gheed Murtadi Male Arabic Speaker . Mohamad Mohamad COURSE WRITERS Dr. Mahdi Alosh ♦ Marie-Pierre Grandin-Gillette EDITORS Shannon Rossi ♦ Mary E. Green REVIEWER Ibtisam Alama EDITOR & EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Beverly D. Heinle PRODUCER Sarah H. McInnis RECORDING ENGINEERS Peter S. Turpin ♦ Kelly Saux Simon & Schuster Studios, Concord, MA iii Modern Standard Arabic 1 Table of Contents Introduction. 1 The Arabic Alphabet . 3 Reading Lessons . 6 Arabic Alphabet Chart . 8 Diacritical Marks . 10 Lesson One . 11 Lesson Two . 12 Lesson Three . 13 Lesson Four . 14 Lesson Five . 15 Lesson Six . 16 Lesson Seven . 17 Lesson Eight . 18 Lesson Nine . 19 Lesson Ten . 20 Lesson Eleven . 21 Lesson Twelve . 22 Lesson Thirteen . 23 Lesson Fourteen . 24 Lesson Fifteen . 25 Lesson Sixteen. 26 Lesson Seventeen . 27 Lesson Eighteen . 28 Lesson Nineteen . 30 Lesson Twenty (with diacritics) . 32 Lesson Twenty (without diacritics) . 34 iv Modern Standard Arabic 1 Introduction Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), also known as Literary or Standard Arabic, is the official language of an estimated 320 million people in the 22 Arab countries represented in the Arab League.