Bats As Bushmeat: a Global Review S Imon M Ickleburgh,Kerry W Aylen and P Aul R Acey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bat Conservation 2021

Bat Conservation Global evidence for the effects of interventions 2021 Edition Anna Berthinussen, Olivia C. Richardson & John D. Altringham Conservation Evidence Series Synopses 2 © 2021 William J. Sutherland This document should be cited as: Berthinussen, A., Richardson O.C. and Altringham J.D. (2021) Bat Conservation: Global Evidence for the Effects of Interventions. Conservation Evidence Series Synopses. University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Cover image: Leucistic lesser horseshoe bat Rhinolophus hipposideros hibernating in a former water mill, Wales, UK. Credit: Thomas Kitching Digital material and resources associated with this synopsis are available at https://www.conservationevidence.com/ 3 Contents Advisory Board.................................................................................... 11 About the authors ............................................................................... 12 Acknowledgements ............................................................................. 13 1. About this book ........................................................... 14 1.1 The Conservation Evidence project ................................................................................. 14 1.2 The purpose of Conservation Evidence synopses ............................................................ 14 1.3 Who this synopsis is for ................................................................................................... 15 1.4 Background ..................................................................................................................... -

Fruit Bats As Natural Foragers and Potential Pollinators in Fruit Orchard: a Reproductive Phenological Study

Journal of Agricultural Research, Development, Extension and Technology, 25(1), 1-9 (2019) Full Paper Fruit bats as natural foragers and potential pollinators in fruit orchard: a reproductive phenological study Camelle Jane D. Bacordo, Ruffa Mae M. Marfil and John Aries G. Tabora Department of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Southern Mindanao, Kabacan, Cotabato, Philippines Received: 27 February 2019 Accepted: 10 June 2019 Abstract Family Pteropodidae could consume either fruit or flower parts to sustain their energy requirement. In some species of fruit bats, population growth is sometimes dependent on the food availability and in return bats could be pollinators of certain species of plants. In this study, 152 female bats captured from the Manilkara zapota orchard of the University of Southern Mindanao were examined for their reproductive stages. Lactation of fruit bat species Ptenochirus jagori and Ptenochirus minor were positively correlated with the fruiting of M. zapota. While the lactation of Cynopterus brachyotis, Eonycteris spelaea and Rousettus amplexicaudatus were positively associated with the flowering of M. zapota. Together, thirty M. zapota trees were observed for their generative stage (fruiting or flowering) in 6 months. Based on the canonical correspondence analysis, only P. jagori was considered as the natural forager as its lactating stage coincides with the fruiting peaks and only C. brachyotis and E. spelaea were the potential pollinators since its lactating stage coincides with the flowering peaks ofM. zapota tree. The method in this study can be used to identify potential pollinators and foragers in other fruit trees. Keywords - agroforest, chiropterophily, frugivore, nocturnal, Sapotaceae Introduction pollination process is called chiropterophily. -

Island Biology Island Biology

IIssllaanndd bbiioollooggyy Allan Sørensen Allan Timmermann, Ana Maria Martín González Camilla Hansen Camille Kruch Dorte Jensen Eva Grøndahl, Franziska Petra Popko, Grete Fogtmann Jensen, Gudny Asgeirsdottir, Hubertus Heinicke, Jan Nikkelborg, Janne Thirstrup, Karin T. Clausen, Karina Mikkelsen, Katrine Meisner, Kent Olsen, Kristina Boros, Linn Kathrin Øverland, Lucía de la Guardia, Marie S. Hoelgaard, Melissa Wetter Mikkel Sørensen, Morten Ravn Knudsen, Pedro Finamore, Petr Klimes, Rasmus Højer Jensen, Tenna Boye Tine Biedenweg AARHUS UNIVERSITY 2005/ESSAYS IN EVOLUTIONARY ECOLOGY Teachers: Bodil K. Ehlers, Tanja Ingversen, Dave Parker, MIchael Warrer Larsen, Yoko L. Dupont & Jens M. Olesen 1 C o n t e n t s Atlantic Ocean Islands Faroe Islands Kent Olsen 4 Shetland Islands Janne Thirstrup 10 Svalbard Linn Kathrin Øverland 14 Greenland Eva Grøndahl 18 Azores Tenna Boye 22 St. Helena Pedro Finamore 25 Falkland Islands Kristina Boros 29 Cape Verde Islands Allan Sørensen 32 Tristan da Cunha Rasmus Højer Jensen 36 Mediterranean Islands Corsica Camille Kruch 39 Cyprus Tine Biedenweg 42 Indian Ocean Islands Socotra Mikkel Sørensen 47 Zanzibar Karina Mikkelsen 50 Maldives Allan Timmermann 54 Krakatau Camilla Hansen 57 Bali and Lombok Grete Fogtmann Jensen 61 Pacific Islands New Guinea Lucía de la Guardia 66 2 Solomon Islands Karin T. Clausen 70 New Caledonia Franziska Petra Popko 74 Samoa Morten Ravn Knudsen 77 Tasmania Jan Nikkelborg 81 Fiji Melissa Wetter 84 New Zealand Marie S. Hoelgaard 87 Pitcairn Katrine Meisner 91 Juan Fernandéz Islands Gudny Asgeirsdottir 95 Hawaiian Islands Petr Klimes 97 Galápagos Islands Dorthe Jensen 102 Caribbean Islands Cuba Hubertus Heinicke 107 Dominica Ana Maria Martin Gonzalez 110 Essay localities 3 The Faroe Islands Kent Olsen Introduction The Faroe Islands is a treeless archipelago situated in the heart of the warm North Atlantic Current on the Wyville Thompson Ridge between 61°20’ and 62°24’ N and between 6°15’ and 7°41’ W. -

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape As A

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape as a Chiropteran Diversity Hotspot in Sumatra Author(s): Joe Chun-Chia Huang, Elly Lestari Jazdzyk, Meyner Nusalawo, Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Sigit Wiantoro, and Tigga Kingston Source: Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2):413-449. Published By: Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/150811014X687369 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3161/150811014X687369 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2): 413–449, 2014 PL ISSN 1508-1109 © Museum and Institute of Zoology PAS doi: 10.3161/150811014X687369 A recent -

Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)

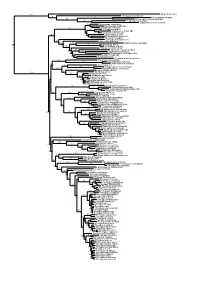

Chapter 6 Phylogenetic Relationships of Harpyionycterine Megabats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) NORBERTO P. GIANNINI1,2, FRANCISCA CUNHA ALMEIDA1,3, AND NANCY B. SIMMONS1 ABSTRACT After almost 70 years of stability following publication of Andersen’s (1912) monograph on the group, the systematics of megachiropteran bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) was thrown into flux with the advent of molecular phylogenetics in the 1980s—a state where it has remained ever since. One particularly problematic group has been the Austromalayan Harpyionycterinae, currently thought to include Dobsonia and Harpyionycteris, and probably also Aproteles.Inthis contribution we revisit the systematics of harpyionycterines. We examine historical hypotheses of relationships including the suggestion by O. Thomas (1896) that the rousettine Boneia bidens may be related to Harpyionycteris, and report the results of a series of phylogenetic analyses based on new as well as previously published sequence data from the genes RAG1, RAG2, vWF, c-mos, cytb, 12S, tVal, 16S,andND2. Despite a striking lack of morphological synapomorphies, results of our combined analyses indicate that Boneia groups with Aproteles, Dobsonia, and Harpyionycteris in a well-supported, expanded Harpyionycterinae. While monophyly of this group is well supported, topological changes within this clade across analyses of different data partitions indicate conflicting phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial partition. The position of the harpyionycterine clade within the megachiropteran tree remains somewhat uncertain. Nevertheless, biogeographic patterns (vicariance-dispersal events) within Harpyionycterinae appear clear and can be directly linked to major biogeographic boundaries of the Austromalayan region. The new phylogeny of Harpionycterinae also provides a new framework for interpreting aspects of dental evolution in pteropodids (e.g., reduction in the incisor dentition) and allows prediction of roosting habits for Harpyionycteris, whose habits are unknown. -

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

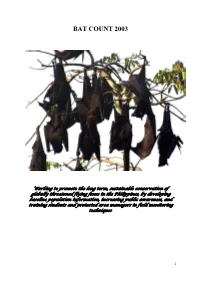

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

ANTIQUITY 2008 (In Press) an Unexpected, Stripe-Faced Flying Fox in Ice Age Rock Art of Australia's Kimberley. “Jack” Pett

ANTIQUITY 2008 (in press) An Unexpected, Stripe-faced Flying Fox in Ice Age Rock Art of Australia’s Kimberley. “Jack” Pettigrew, Marilyn Nugent, Anscar McPhee, Josh Wallman Bradshaw rock art of northern Australia enjoys continuing controversy concerning what community painted them and how to interpret the images (Roy 2002). The keen observation and accurate depictions of the natural world shown here, as well as the extraordinary longevity of the stains used, all tend to support the side of the controversy that posits a distinct cultural entity. We describe a painting unmistakably depicting flying foxes with features not found in bats presently found in Australia. Thermoluminescence dating of wasp nest overlying the art suggests an ice age migration to Australia, either of the bats or of the artists who painted them, a more likely scenario biologically than younger dates. The bat depictions were found on a sandstone wall protected by overhangs, near Kalumburu (14.30 °S; 126.64 °E), amongst other walls showing characteristic Bradshaw art (Walsh 2002). The depiction shows eight roosting megabats (flying foxes, Family Pteropodidae, sub-Order Megachiroptera) hanging from a slender branch, or more likely, a vine (Figs 1,2). Each bat has a distinctive white facial stripe and pale belly (Fig. 3). Figure1. White-striped flying foxes depicted in Bradshaw rock art at Kalumburu, in the Kimberley of Western Australia. Figure 2. Extension, to the left, of the same depicted group of shown in Fig. 1, with which there is some overlap. Dating: The indelible inks used in Bradshaw art penetrate more than a millimetre into the sandstone but have resisted all attempts so far to date them directly, with a number of different estimates of their age (Michaelson and Ebersole 2000). -

Final Report on the Project

BP Conservation Programme (CLP) 2005 PROJECT NO. 101405 - BRONZE AWARD WINNER ECOLOGY, DISTRIBUTION, STATUS AND PROTECTION OF THREE CONGOLESE FRUIT BATS FINAL REPORT Patrick KIPALU Team Leader Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement OCPE – ong Kinshasa – Democratic Republic of the Congo E-mail: [email protected] APRIL 2009 1 Table of Content Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………. p3 I. Project Summary……………………………………………………………….. p4 II. Introduction…………………………………………………………………… p4-p7 III. Materials and Methods ……………………………………………………….. p7-p10 IV. Results per Study Site…………………………………………………………. p10-p15 1. Pointe-Noire ………………………………………………………….. p10-p12 2. Mayumbe Forest /Luki Reserve……………………………………….. p12-p13 3. Zongo Forest…………………………………………………………... p14 4. Mbanza-Ngungu ………………………………………………………. P15 V. General Results ………………………………………………………………p15-p16 VI. Discussions……………………………………………………………………p17-18 VII. Conclusion and Recommendations……………………………………….p 18-p19 VIII. Bibliography………………………………………………………………p20-p21 Acknowledgements 2 The OCPE (Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement) project team would like to start by expressing our gratefulness and saying thank you to the BP Conservation Program, which has funded the execution of this project. The OCPE also thanks the Van Tienhoven Foundation which provided a further financial support. Without these organisations, execution of the project would not have been possible. We would like to thank specially the BPCP “dream team”: Marianne D. Carter, Robyn Dalzen and our regretted Kate Stoke for their time, advices, expertise and care, which helped us to complete this work, Our special gratitude goes to Dr. Wim Bergmans, who was the hero behind the scene from the conception to the execution of the research work. Without his expertise, advices and network it would had been difficult for the project team to produce any result from this project. -

Species-Edition-Melanesian-Geo.Pdf

Nature Melanesian www.melanesiangeo.com Geo Tranquility 6 14 18 24 34 66 72 74 82 6 Herping the final frontier 42 Seahabitats and dugongs in the Lau Lagoon 10 Community-based response to protecting biodiversity in East 46 Herping the sunset islands Kwaio, Solomon Islands 50 Freshwater secrets Ocean 14 Leatherback turtle community monitoring 54 Freshwater hidden treasures 18 Monkey-faced bats and flying foxes 58 Choiseul Island: A biogeographic in the Western Solomon Islands stepping-stone for reptiles and amphibians of the Solomon Islands 22 The diversity and resilience of flying foxes to logging 64 Conservation Development 24 Feasibility studies for conserving 66 Chasing clouds Santa Cruz Ground-dove 72 Tetepare’s turtle rodeo and their 26 Network Building: Building a conservation effort network to meet local and national development aspirations in 74 Secrets of Tetepare Culture Western Province 76 Understanding plant & kastom 28 Local rangers undergo legal knowledge on Tetepare training 78 Grassroots approach to Marine 30 Propagation techniques for Tubi Management 34 Phantoms of the forest 82 Conservation in Solomon Islands: acts without actions 38 Choiseul Island: Protecting Mt Cover page The newly discovered Vangunu Maetambe to Kolombangara River Island endemic rat, Uromys vika. Image watershed credit: Velizar Simeonovski, Field Museum. wildernesssolomons.com WWW.MELANESIANGEO.COM | 3 Melanesian EDITORS NOTE Geo PRODUCTION TEAM Government Of Founder/Editor: Patrick Pikacha of the priority species listed in the Critical Ecosystem [email protected] Solomon Islands Hails Partnership Fund’s investment strategy for the East Assistant editor: Tamara Osborne Melanesian Islands. [email protected] Barana Community The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) Contributing editor: David Boseto [email protected] is designed to safeguard Earth’s most biologically rich Prepress layout: Patrick Pikacha Nature Park Initiative and threatened regions, known as biodiversity hotspots. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Investigating the Role of Bats in Emerging Zoonoses

12 ISSN 1810-1119 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF BATS IN EMERGING ZOONOSES Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interest Cover photographs: Left: © Jon Epstein. EcoHealth Alliance Center: © Jon Epstein. EcoHealth Alliance Right: © Samuel Castro. Bureau of Animal Industry Philippines 12 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF BATS IN EMERGING ZOONOSES Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interest Edited by Scott H. Newman, Hume Field, Jon Epstein and Carol de Jong FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2011 Recommended Citation Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. 2011. Investigating the role of bats in emerging zoonoses: Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interests. Edited by S.H. Newman, H.E. Field, C.E. de Jong and J.H. Epstein. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 12. Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO.