Research of the Worn in the Donors' Portraits in the Unearthed Artworks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs Into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8

DOI: 10.4312/as.2019.7.2.47-86 47 Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8 ∗∗ Nataša VAMPELJ SUHADOLNIK 9 Abstract This paper examines the ways in which Fuxi and Nüwa were depicted inside the mu- ral tombs of the Wei-Jin dynasties along the Hexi Corridor as compared to their Han counterparts from the Central Plains. Pursuing typological, stylistic, and iconographic approaches, it investigates how the western periphery inherited the knowledge of the divine pair and further discusses the transition of the iconographic and stylistic design of both deities from the Han (206 BCE–220 CE) to the Wei and Western Jin dynasties (220–316). Furthermore, examining the origins of the migrants on the basis of historical records, it also attempts to discuss the possible regional connections and migration from different parts of the Chinese central territory to the western periphery. On the basis of these approaches, it reveals that the depiction of Fuxi and Nüwa in Gansu area was modelled on the Shandong regional pattern and further evolved into a unique pattern formed by an iconographic conglomeration of all attributes and other physical characteristics. Accordingly, the Shandong region style not only spread to surrounding areas in the central Chinese territory but even to the more remote border regions, where it became the model for funerary art motifs. Key Words: Fuxi, Nüwa, the sun, the moon, a try square, a pair of compasses, Han Dynasty, Wei-Jin period, Shandong, migration Prenos slikovnih motivov na zahodno periferijo: Fuxi in Nüwa v grobnicah s poslikavo iz obdobja Wei Jin na območju prehoda Hexi Izvleček Pričujoči prispevek v primerjalni perspektivi obravnava upodobitev Fuxija in Nüwe v grobnicah s poslikavo iz časa dinastij Wei in Zahodni Jin (220–316) iz province Gansu * The author acknowledges the financial support of the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) in the framework of the research core funding Asian languages and Cultures (P6-0243). -

The Use of Digital Technologies to Enhance User Experience at Gansu Provincial Museum

The Use of Digital Technologies to Enhance User Experience at Gansu Provincial Museum Jun E1, Feng Zhao2, Soo Choon Loy2 1 Gansu Provincial Museum, Lanzhou, 3 Xijnxi Road 2 Amber Digital Solutions, Beijing, Shijingshan, 74 Lugu Road, Zhongguo Ruida Building, F809, 100040, China [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. This paper discusses the critical issues faced by Gansu Provincial Museum in attracting and maintaining its audiences, and how it engages digital technology to create new compelling exhibits via the use of both digital and multimedia tools. Real life examples using virtual reality, augmented reality and interactive games will be briefly discussed. Keywords: Smart Museum, CAVE, Sand Model, Digitization 1 Introduction As digital technology evolves, more and more conventional museums are exploring new and innovative methods to go beyond the mere display of physical artefacts. Gansu provincial museum is no otherwise. The urge to engage technologies becomes stronger as visitors become more affluent and are seeking more enriching experiences that digital technologies can provide. Technologies that can share deeper contextual information about the museum’s cultural artefacts include touch screens, projectors, multi-medias, virtual reality and interactive games. However, all these are made possible and be exploited to the very best only if the cultural exhibits are digitally available. Digital exhibits provide opportunities for the production of new information by recreating interactive models and incorporating visual and sound effects. Such end products form better and efficient tools for disseminating valuable information about the artefacts than if they were merely displayed physically. 1.1 Objectives of the paper This paper discusses how Gansu Provincial Museum engages digital technology to resolve its main issue of creating new compelling exhibits via the use of both digital and multimedia tools. -

Three Kingdoms Unveiling the Story: List of Works

Celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the Japan-China Cultural Exchange Agreement List of Works Organizers: Tokyo National Museum, Art Exhibitions China, NHK, NHK Promotions Inc., The Asahi Shimbun With the Support of: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, NATIONAL CULTURAL HERITAGE ADMINISTRATION, July 9 – September 16, 2019 Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Japan With the Sponsorship of: Heiseikan, Tokyo National Museum Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd., Notes Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance Co.,Ltd., MITSUI & CO., LTD. ・Exhibition numbers correspond to the catalogue entry numbers. However, the order of the artworks in the exhibition may not necessarily be the same. With the cooperation of: ・Designation is indicated by a symbol ☆ for Chinese First Grade Cultural Relic. IIDA CITY KAWAMOTO KIHACHIRO PUPPET MUSEUM, ・Works are on view throughout the exhibition period. KOEI TECMO GAMES CO., LTD., ・ Exhibition lineup may change as circumstances require. Missing numbers refer to works that have been pulled from the JAPAN AIRLINES, exhibition. HIKARI Production LTD. No. Designation Title Excavation year / Location or Artist, etc. Period and date of production Ownership Prologue: Legends of the Three Kingdoms Period 1 Guan Yu Ming dynasty, 15th–16th century Xinxiang Museum Zhuge Liang Emerges From the 2 Ming dynasty, 15th century Shanghai Museum Mountains to Serve 3 Narrative Figure Painting By Qiu Ying Ming dynasty, 16th century Shanghai Museum 4 Former Ode on the Red Cliffs By Zhang Ruitu Ming dynasty, dated 1626 Tianjin Museum Illustrated -

LCT - Silk Road & Xinjiang - 15D-01

www.lilysunchinatours.com 15-day Silk Road and Xinjiang Tour Tour code: LCT - Silk Road & Xinjiang - 15D-01 Attractions: Overview: This two-week trip will take you to explore the most mysterious parts of China, Gansu and Xinjiang Province, to pursue the old Silk Road. Starting from Lanzhou, you will visit a number of historical places and natural wonders until the last city Karmay. A private guide and driver will be arranged to navigate your way through the exotic places to make sure everything go well. Highlights: 1. Take a boat to visit the hidden gem of Lanzhou - Bingling Thousand -Buddha Caves; 2. Immerse yourself in the magnificence of the Rainbow Mountains in Zhangye Danxia Landform Park; 3. Meet the unbreakable pass - Jiayuguan Pass; 4. Appreciate the murals and paintings inside the Mogao Caves; 5. Explore the ruins of Jiaohe Ancient Town and taste the yummy Xinjiang fruits; 6. Unveil the secrets of Karez Irrigation System; 7. Experience the Grand Bazaar of Xinjiang and feel the hospitality of local people; 8. Relax at the picturesque Heavenly Lake and listen to the beautiful legends; 9. Pay a visit to a Tuva Family and enjoy the raw, primitive grassland scenery; 10. Challenge yourself with the “horrible” Urho Ghost City in Karamy. Detailed Itinerary: Day 1: Welcome to Lanzhou! A private car & driver will be arranged to pick you uppon your arrival and transfer you to your hotel. You may spend the rest of the day adjust or have some activities on uyour own. Tel: +86 18629295068 / 1-909-666-8151 (toll free) Email: [email protected] www.lilysunchinatours.com Day 2: Bingling Thousand-Buddha Caves, Gansu Provincial Museum 08:00: Your Lanzhou local expert will meet you at your hotel lobby and take you to explore the amazing Lanzhou city. -

Gansu Kina 24.2 Til 10.3 2013

Gansu Kina 24.2 til 10.3 2013 自强不息,独树一帜 motto oversat: Be diligent, be realistic, be enterprising 1 Deltagere Billy Bjarne Kristensen Ejvind Frausing Hansen Jørgen Jesper Hvolris Lisbeth Hvolris Nina Weis Otto Kraemer Ove Andersen Torben Mogensen Lars Bo Krag Møller Denne lille folder er udarbejdet forud for turen til Kina den 24.2 til 10.3 2013. Den består af klip fra nettet (Wikipedia, FDM travel mf) Indholdet er ikke kontrolleret. lkm 2 Indhold Forside 2 Geografien og populationen 5 Billeder fra Lanzhou 6 Lanzhou new area 7 Lanzhous adminstration 9 Historie, klima, geografi mm 10 Et rejsebureau beskrivelse 11 Geografi og klima 13 Transport 15 Industri og transport 14 Lanzhou universitet 16 Laboratorier 17 Nøgletal for universitetet 18 Ganshou 18 Kort 23 Beijing (kort over) 27 Undgå at blive snydt/seværdigheder 28 Praktiske forhold 29 3 Kina 甘 gān ‐ Ganzhou (Zhangye) Navnets oprindelse 肃 sù ‐ Suzhou (Jiuquan) Administrationstype Provins Hovedstad Lanzhou Guvernør Lu Hao Ganzhou Areal 454.000 km² (7.) Befolkning (2004) 26.190.000 (22.) ‐ Tæthed 57,7/km² (27.) CNY 155,9 milliard BNI (2004) (27.) ‐ per indbygger CNY 5950 (30.) Officiel hjemmeside: http://www.gansu.gov.cn Gansu (simplificeret kinesisk: 甘 Hovedstaden:Lanzhou 肃, traditionel kinesisk: 甘肅,Hanyu Pinyin: Gānsù, Wade‐Giles: Kan‐su, Kansu Bypræfekturerne eller Kan‐suh) er Lanzhou (7) en provins i Folkerepublikken Kina. (af 22 Jinchang (4) provinser) . Den ligger Baiyin (6) mellem Qinghai, Indre Mongoliet og Tianshui (12) Huangtu‐plateauet og grænser op Jiayuguan (2) Wuwei (5) til Mongoliet i nord. Huang He‐floden Zhangye (3) løber gennem den sydlige del af Pingliang (13) provinsen. -

Cultural Connections Gain Fresh Life with Touring Exhibitions, Museums Play Role in Deepening Mutual Understanding

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Tuesday, April 27, 2021 | 11 WORLD TIES THAT BIND Cultural connections gain fresh life With touring exhibitions, museums play role in deepening mutual understanding Editor’s note: People-to-people “I’m looking forward to how it will exchanges are deepening the spotlight the many existing cultural connections between countries and artistic exchanges between our participating in the Belt and Road home region and China,” he says. Initiative. This column celebrates Xu He, the project leader of the the efforts of those working toward International Liaison Office of Art a shared future. Exhibitions China, says that in the years before the pandemic forced the By CHEN YINGQUN closure of borders, the organization [email protected] had brought an increasing number of art exhibits to audiences in coun- When Maryam Mohsin Hassan tries involved in the BRI. In 2014, the Abdalla visited Gansu Provincial exhibition Treasures of China was Museum in 2016, she was impressed held in Tanzania and, in the follow- by its exotic charm and mixture of ing year, the center curated exhibi- Eastern and Western cultures. tions on China’s general history in The 23-year-old Sudanese, from Latvia, Lithuania and Cyprus. Khartoum, recalls she was enchanted In 2016, the Treasures of China by a series of exhibitions at the muse- exhibition was taken to the Museum um in Lanzhou, in China’s Northwest. of Islamic Art in Qatar, bringing Chi- These included the Silk Road Exhibi- na’s Terracotta Warriors to people in tion and the Buddhist Art of Gansu. -

Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田

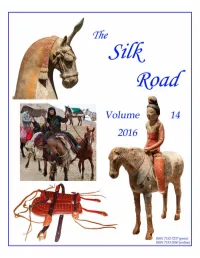

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 14 2016 Contents From the editor’s desktop: The Future of The Silk Road ....................................................................... [iii] Reconstruction of a Scythian Saddle from Pazyryk Barrow № 3 by Elena V. Stepanova .............................................................................................................. 1 An Image of Nighttime Music and Dance in Tang Chang’an: Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田 ................................................................................................................ 19 The Results of the Excavation of the Yihe-Nur Cemetery in Zhengxiangbai Banner (2012-2014) by Chen Yongzhi 陈永志, Song Guodong 宋国栋, and Ma Yan 马艳 .................................. 42 Art and Religious Beliefs of Kangju: Evidence from an Anthropomorphic Image Found in the Ugam Valley (Southern Kazakhstan) by Aleksandr Podushkin .......................................................................................................... 58 Observations on the Rock Reliefs at Taq-i Bustan: A Late Sasanian Monument along the “Silk Road” by Matteo Compareti ................................................................................................................ 71 Sino-Iranian Textile Patterns in Trans-Himalayan Areas by Mariachiara Gasparini ....................................................................................................... -

Questions of Ancient Human Settlements in Xinjiang and the Early Silk Road Trade, with an Overview of the Silk Road Research

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 185 November, 2008 Questions of Ancient Human Settlements in Xinjiang and the Early Silk Road Trade, with an Overview of the Silk Road Research Institutions and Scholars in Beijing, Gansu, and Xinjiang by Jan Romgard Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series edited by Victor H. Mair. The purpose of the series is to make available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including Romanized Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino-Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. The only style-sheet we honor is that of consistency. Where possible, we prefer the usages of the Journal of Asian Studies. Sinographs (hanzi, also called tetragraphs [fangkuaizi]) and other unusual symbols should be kept to an absolute minimum. -

The Development and Regional Variations of Liubo

ARTICLES The Development and Regional Variations of Liubo Yasuji Shimizu (Translated by Kumiko Tsutsui) Abstract: This paper clarified the transition of liubo game boards with re- spect to both chronological order and genealogical relationships based on re- cent evidence. In spite of the limited direct access to many of the relics due to the organic material used in most of the liubo items, I believe that an over- all understanding of liubo was achieved. Each type of liubo board was used concurrently over a long period of time. Despite limited evidence, regional variation in the game boards was identified. However, more new evidence may yield different interpretations and require reexamination in the future. The results indicate that typical board design could be traced back to an- cient liubo and the T motif of the TLV pattern could be a relatively newer innovation. Interpreting the typical TLV pattern based on the \circular sky and square earth" cosmology was deemed as inappropriate for this research. This study was conducted mainly based on liubo artifacts, and graphic documents, such as illustrated stones, were taken only into secondary con- sideration. I hope to conduct further examination and exploration of liubo based on graphic materials in the near future. Keywords: Liubo, TLV pattern, divination, bronze mirror, sundials Introduction As has been theorized for other ancient board games [23], the origin of the Chinese ancient board game liubo (|¿) is believed to be related to divination and oracle reading. In fact, archeological evidence and historical documents support liubo's strong relationship with divination. For example, in Qin's Zhanguoce (Art of War.国策), there is a story about one boy who plays liubo by throwing dice in place of the gods. -

Aug 31, 2016 the Life of the Buddha at Chinese Buddhist Cave Complexes

The life of the Buddha at Chinese Buddhist cave complexes in Northwestern and Central China Dessislava Vendova Columbia University SRA2015-2 My dissertation topic and the main aspect of my PhD research is on Buddha’s extended biography which includes the narratives of his past lives (known as jataka tales) and also the story of his last life as Gotama Sakyamuni and I’m particularly interested in examining the role of the narrative and visual representations of the Buddha’s life story for the early spread of Buddhism. The tentative title of my doctoral dissertation is: “The Great Life of the Body of Buddha: Re- examination and re-assessment of the images and narratives of the life of Buddha Shakyamuni”. My dissertation will be a textual and iconographic re-examination of the connections between Buddhist narratives (and in particular the extended biography of the Buddha) and Buddhist images and will be focusing on the exploration of the connections between textual and iconographic representations of Buddha’s lives stories, and also the body of Buddha as depicted in Buddhist narratives and their visual iconic representations and will be a reassessment of the role and significance of narratives about the life of the Buddha and the produced images for the spread of Buddhism from India through Central Asia to China. Buddhist images, Buddhist cave temples and the role of visual representation of narratives at early Buddhist sites seems have undoubtedly had a very significant role for the spread of Buddhism and is a phenomenon that started in India, developed in Central Asia and then found new development in China. -

Iranian and Hellenistic Architectural Elements in Chinese Art

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 274 February, 2018 Iranian and Hellenistic Architectural Elements in Chinese Art by Kateřina Svobodová Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. We do, however, strongly recommend that prospective authors consult our style guidelines at www.sino-platonic.org/stylesheet.doc. -

Participation of Dr. B. L. Malla Yinchuan of Ninxia Province Post

Participation of Dr. B. L. Malla In At Yinchuan of Ninxia Province & Post Festival Field Investigations on Jiayuguan Heishan Mountain Rock Art of Gansu province (China) th st (15 -25 July, 2017) ADI DRISHYA DEPARTMENT INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL CENTRE FOR THE ARTS NEW DELHI 1 I The 2017 International Rock Art Festival of Helan Mountain Rock Art at Yinchuan (Ninxia Province) and the Post Festival Symposiums and Field Investigations on Jiayuguan Heishan Mountain Rock Art (Gansu province) in China was held from 15th-25st July, 2017. The events(s) was jointly organised by The Administration of Rock Art, Helan Mountain, Yinchuan; Centre for Rock Art Study & Exchange, Helan Mountain; Institute of Rock Art Protection and Research, Helan Mountain; Yinchuan Bureau of Culture, Broadcasting, Television, Press and Publication; Yinchuan Sports Tourism Bureau; Yinchuan Literature Art Association; Yinchuan News Media Group; Han Meilin Art Museum; Helan Mountain Cultural Tourism Investment and development Co. Ltd.; Academy of Jiayu Pass Silk Road (the Great Wall) and Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou. Helanshan Rock Art On day one (16/07/2017) after breakfast, as per the programme, the delegates were taken to the Helanshan Rock Art Park for the opening ceremony of the festival. The internationally renowned Chinese artist Han Mei Lin formally inaugurated the event and equally internationally reputed rock art expert from Italy Professor Rock Art Festival of Helan Mountain Rock Art at Yinchuan inaugurated by internationally renowned Chinese artist Han Mei Lin Emmanuel Anati gave the keynote address at this occasion. Dr. B. L. Malla represented the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), New Delhi (India) in the event.