UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

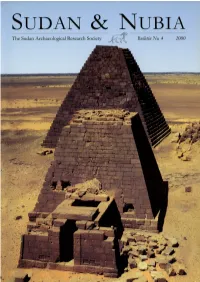

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Buhen in the New Kingdom

Buhen in the New Kingdom George Wood Background - Buhen and Lower Nubia before the New Kingdom Traditionally ancient Egypt ended at the First Cataract of the Nile at Elephantine (modern Aswan). Beyond this lay Lower Nubia (Wawat), and beyond the Dal Cataract, Upper Nubia (Kush). Buhen sits just below the Second Cataract, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite modern Wadi Halfa, at what would have been a good location for ships to carry goods to the First Cataract. The resources that flowed from Nubia included gold, ivory, and ebony (Randall-MacIver and Woolley 1911a: vii, Trigger 1976: 46, Baines and Málek 1996: 20, Smith, ST 2004: 4). Egyptian operations in Nubia date back to the Early Dynastic Period. Contact during the 1st Dynasty is linked to the end of the indigenous A-Group. The earliest Egyptian presence at Buhen may have been as early as the 2nd Dynasty, with a settlement by the 3rd Dynasty. This seems to have been replaced with a new town in the 4th Dynasty, apparently fortified with stone walls and a dry moat, somewhat to the north of the later Middle Kingdom fort. The settlement seems to have served as a base for trade and mining, and royal seals from the 4th and 5th Dynasties indicate regular communications with Egypt (Trigger 1976: 46-47, Baines and Málek 1996: 33, Bard 2000: 77, Arnold 2003: 40, Kemp 2004: 168, Bard 2015: 175). The latest Old Kingdom royal seal found was that of Nyuserra, with no archaeological evidence of an Egyptian settlement after the reign of Djedkara. -

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Applying a Multi- Analytical Approach to the Investigation of Ancient Egyptian Influence in Nubian Communities: The Socio- Cultural Implications of Chemical Variation in Ceramic Styles Julia Carrano Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Stuart T. Smith Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara George Herbst Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Gary H. Girty Department of Geological Sciences, San Diego State University Carl J. Carrano Department of Chemistry, San Diego State University Jeffrey R. Ferguson Archaeometry Laboratory, Research Reactor Center, University of Missouri Abstract is article reviews published archaeological research that explores the potential of combined chemical and petrographic analyses to distin - guish manufacturing methods of ceramics made om Nile river silt. e methodology was initially applied to distinguish the production methods of Egyptian and Nubian- style vessels found in New Kingdom and Napatan Period Egyptian colonial centers in Upper Nubia. Conducted in the context of ongoing excavations and surveys at the third cataract, ceramic characterization can be used to explore the dynamic role pottery production may have played in Egyptian efforts to integrate with or alter native Nubian culture. Results reveal that, despite overall similar geochemistry, x-ray fluorescence (XRF), instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA), and petrography can dis - tinguish Egyptian and Nubian- -

Sphinx Sphinx

SPHINX SPHINX History of a Monument CHRISTIANE ZIVIE-COCHE translated from the French by DAVID LORTON Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Original French edition, Sphinx! Le Pen la Terreur: Histoire d'une Statue, copyright © 1997 by Editions Noesis, Paris. All Rights Reserved. English translation copyright © 2002 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2002 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zivie-Coche, Christiane. Sphinx : history of a moument / Christiane Zivie-Coche ; translated from the French By David Lorton. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8014-3962-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Great Sphinx (Egypt)—History. I.Tide. DT62.S7 Z58 2002 932—dc2i 2002005494 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materi als include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further informa tion, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 987654321 TO YOU PIEDRA en la piedra, el hombre, donde estuvo? —Canto general, Pablo Neruda Contents Acknowledgments ix Translator's Note xi Chronology xiii Introduction I 1. Sphinx—Sphinxes 4 The Hybrid Nature of the Sphinx The Word Sphinx 2. -

The Kingdom of Kush

Age of Empires Kush/ Nubia was an African Kingdom located to the south of Egypt Their close relationship with Egypt is evident on walls of Egyptian tombs and temples Next to Egypt, Kush was the greatest ancient civilization in Africa Kush was known for its rich gold mines Nub = gold in Egyptians Important trading hub Egyptian goods = grain, beer, linen Kush goods = gold, ivory, leather, timber Egypt often raided Kush and took control of parts of its territory Kush paid tribute to the pharaoh While under Egypt’s control, Kush became “Egyptianized” Kushites spoke Egyptian Worshipped same gods/goddesses Hired into the Egyptian Army Kush royal family was educated in Egypt After the collapse of the New Kingdom, there was a serious of weak and ineffective rulers causing Egypt to become extremely weak 730 B.C.E. Kush invaded and Egypt surrendered to King Piye Piye declared himself Pharaoh and “Uniter, of the Two Lands” Kushite pharaohs ruled Egypt for over 100 years Did not destroy Egyptian culture, but adapted Kushites were driven out by the Assyrians Meroe was safe out of Egypt's reach since they destroyed Napata (their previous capital) Important center of trade Production of iron Broke away from Egyptian tradition Had female leadership= kandakes or queen mothers Worshiped an African Lion god instead of Egyptian gods Story of Nubia www.youtube.com This short documentary tells the story of Nubia and the civilization that flourished in the Nile Valley for thousands of years and particularly between 800 BC and 400 .... -

Kush Under the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (C. 760-656 Bc)

CHAPTER FOUR KUSH UNDER THE TWENTY-FIFTH DYNASTY (C. 760-656 BC) "(And from that time on) the southerners have been sailing northwards, the northerners southwards, to the place where His Majesty is, with every good thing of South-land and every kind of provision of North-land." 1 1. THE SOURCES 1.1. Textual evidence The names of Alara's (see Ch. 111.4.1) successor on the throne of the united kingdom of Kush, Kashta, and of Alara's and Kashta's descen dants (cf. Appendix) Piye,2 Shabaqo, Shebitqo, Taharqo,3 and Tan wetamani are recorded in Ancient History as kings of Egypt and the c. one century of their reign in Egypt is referred to as the period of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.4 While the political and cultural history of Kush 1 DS ofTanwetamani, lines 4lf. (c. 664 BC), FHNI No. 29, trans!. R.H. Pierce. 2 In earlier literature: Piankhy; occasionally: Py. For the reading of the Kushite name as Piye: Priese 1968 24f. The name written as Pyl: W. Spiegelberg: Aus der Geschichte vom Zauberer Ne-nefer-ke-Sokar, Demotischer Papyrus Berlin 13640. in: Studies Presented to F.Ll. Griffith. London 1932 I 71-180 (Ptolemaic). 3 In this book the writing of the names Shabaqo, Shebitqo, and Taharqo (instead of the conventional Shabaka, Shebitku, Taharka/Taharqa) follows the theoretical recon struction of the Kushite name forms, cf. Priese 1978. 4 The Dynasty may also be termed "Nubian", "Ethiopian", or "Kushite". O'Connor 1983 184; Kitchen 1986 Table 4 counts to the Dynasty the rulers from Alara to Tanwetamani. -

A LIFE COURSE APPROACH to HEALTH in the ANCIENT NILE VALLEY by Katie M

A LIFE COURSE APPROACH TO HEALTH IN THE ANCIENT NILE VALLEY by Katie M. Whitmore A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology West Lafayette, Indiana December 2019 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. Michele Buzon, Chair Department of Anthropology Dr. Sherylyn Briller Department of Anthropology Dr. H. Kory Cooper Department of Anthropology Dr. Stuart Tyson Smith Department of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara Approved by: Dr. Melissa J. Remis 2 Dedicated to my family 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of many individuals and organizations contributed to the completion of this research and thanks are due to all. Financial support for this research was made possible through the Purdue University Research Foundation Grant, the Department of Anthropology at Purdue University, and the Humanities Without Walls Grand Research Challenge: “The Work of the Humanities in a Changing Climate”. Foremost, I would like to thank my advisor Dr. Michele Buzon. Her support throughout my PhD was invaluable to my progression as a researcher, as a scholar, and the completion of this dissertation. She supported me in various ways as my path took me in new and different directions. Her assistance and contributions go beyond what can be stated here. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Drs. Sherri Briller, Kory Cooper, and Stuart Tyson Smith for their excellent mentorship and support, which greatly contributed to a well-rounded dissertation. During my PhD I spent five wonderful field seasons in Sudan under directors Drs. -

Egypt and Africa Presentation.Pdf

Egypt and Africa Map of the Second Cataract showing fortress area Different plan types of Nubian fortresses: Cataract fortresses Plains fortresses Fortress at Buhen: Plains Fortress Defensive Characteristics Askut: Cataract Fort Middle Kingdom institutions as shown by seal impressions First Semna Stela of Senwosret III Southern boundary, made in the year 8, under the majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Khakaure Senwosret III who is given life forever and ever; in order to prevent that any Nubian should cross it, by water or by land, with a ship or with any herds of the Nubians, except a Nubian who shall come to do trading in Iqen (Mirgissa) or with a commission. Every good thing shall be done with them, but without allowing a ship of the Nubians to pass by Heh, going downstream, forever. Boundary Stela of Senwosret III from Semna (a duplicate found at Uronarti) “…I have made my boundary further south than my fathers, I have added to what was bequeathed me. I am a king who speaks and acts, What my heart plans is done by my arm… Attack is valor, retreat is cowardice, A coward is he who is driven from his border. Since the Nubian listens to the word of mouth, To answer him is to make him retreat. Attack him, he will turn his back, Retreat, he will start attacking. They are not people one respects, They are wretches, craven-hearted… As for any son of mine who shall maintain this border which my majesty has made, he is my son, born to my majesty. -

Mud-Brick Architecture

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Mud-Brick Architecture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4983w678 Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Emery, Virginia L. Publication Date 2011-02-19 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California MUD-BRICK ARCHITECTURE عمارة الطوب اللبن Virginia L. Emery EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief Area Editor Material Culture University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor University of Oxford JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Emery, 2011, Mud-Brick Architecture. UEE. Full Citation: Emery, Virginia L., 2011, Mud-Brick Architecture. In Willeke Wendrich (ed.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0026w9hb 1146 Version 1, February 2011 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0026w9hb MUD-BRICK ARCHITECTURE عمارة الطوب اللبن Virginia L. Emery Ziegelarchitektur L’architecture en brique crue Mud-brick architecture, though it has received less academic attention than stone architecture, was in fact the more common of the two in ancient Egypt; unfired brick, made from mud, river, or desert clay, was used as the primary building material for houses throughout Egyptian history and was employed alongside stone in tombs and temples of all eras and regions. Construction of walls and vaults in mud-brick was economical and relatively technically uncomplicated, and mud-brick architecture provided a more comfortable and more adaptable living and working environment when compared to stone buildings. على الرغم أن العمارة بالطوب اللبن تلقت إھتماما أقل من العمارة الحجرية من قِبَل المتخصصين، فقد كانت في الواقع تلك العمارة ھي اﻷكثر شيوعا في مصر القديمة، وكان الطوب اللبن (أوالنيء) المصنوع من الطمي أو الطين الصحراوي مستخدما كمادة بناء بدائية للمنازل على مدار التاريخ المصري واستخدمت إلى جانب الحجارة في المقابر والمعابد في جميع المناطق وخﻻل جميع الفترات. -

Lesson 3 Egypt.Pdf

NAME _________________________________________ DATE _____________ CLASS _______ Ancient Egypt and Kush Lesson 3 Egypt’s Empire ESSENTIAL QUESTION Terms to Know incense a material burned for its pleasant smell Why do civilizations rise and fall? envoy a person who represents his country in a GUIDING QUESTIONS foreign place 1. Why was the Middle Kingdom a “golden age” for Egypt? 2. Why was the New Kingdom a unique period in ancient Egypt’s history? 3. How did two unusual pharaohs change ancient Egypt? 4. Why did the Egyptian empire decline in the late 1200s b.c.? When did it happen? 5000 b.c. 3000 b.c. 2000 b.c. 1000 b.c. 750 b.c. 5000 b.c. 2600 b.c. 2055 b.c. 1070 b.c. 750 b.c. Settlement Old Kingdom Middle New Kingdom Kush begins in Nile begins Kingdom ends conquers River valley begins Egypt You Are Here in History What do you know? Read the list of pharaohs. Circle the names that you know or have heard before. For each circled name, write one fact that you know about that pharaoh. Ahmose Hatshepsut Copyright by McGraw-Hill Education. Thutmose III Akhenaton King Tut Ramses II 49 NAME _________________________________________ DATE _____________ CLASS _______ Ancient Egypt and Kush Lesson 3 Egypt’s Empire, Continued A Golden Age The Middle Kingdom lasted from about 2055 b.c. to 1650 b.c. It was a time of power, wealth, and achievement for Egypt. During the Middle Kingdom, Egypt took control of new lands. The Categorizing pharaoh required tribute, or payments from the conquered peoples. -

Page 60 Next Page >

< previous page page_60 next page > Page 60 2 The intellectual foundations of the early state With the imagined community—the nation—people feel that they share bonds of common interest and inherited values with others, most of whom they will never see. It is a vision of people. By contrast, the state is a vision of power, a mixture of myth and procedure that twines itself amidst the sense of community, giving it political structure. In the modern world the state has become the universal unit of supreme organization. No part of the land of planet Earth does not belong to one. Like it or not most people are born members of a state, even if they live in remote and isolated communities. The stateless are the disadvantaged of the world, anachronistic. Its powers have grown so inescapable that, at least in the English language, the word ‘state’ has taken on a sinister overtone. What are the roots of this condition, this vast surrender by the many and presumption by the few? People have recognized the state as an abstract entity only since the time of the Classical Greeks. But the real history of the state is much longer. If we move further back in time to the early civilizations—of which Egypt was one—we can observe the basic elements of modern states already present and functioning vigorously, yet doing so in the absence of objective awareness of what was involved. The existence of the state was either simply taken for granted or presented in terms which do not belong to the vocabulary of reason and philosophy which is part of our inheritance from the Classical world.