Buhen in the New Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

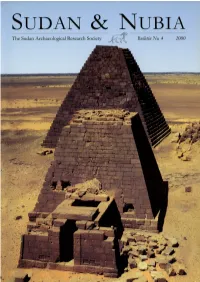

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Egypt and Africa Presentation.Pdf

Egypt and Africa Map of the Second Cataract showing fortress area Different plan types of Nubian fortresses: Cataract fortresses Plains fortresses Fortress at Buhen: Plains Fortress Defensive Characteristics Askut: Cataract Fort Middle Kingdom institutions as shown by seal impressions First Semna Stela of Senwosret III Southern boundary, made in the year 8, under the majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Khakaure Senwosret III who is given life forever and ever; in order to prevent that any Nubian should cross it, by water or by land, with a ship or with any herds of the Nubians, except a Nubian who shall come to do trading in Iqen (Mirgissa) or with a commission. Every good thing shall be done with them, but without allowing a ship of the Nubians to pass by Heh, going downstream, forever. Boundary Stela of Senwosret III from Semna (a duplicate found at Uronarti) “…I have made my boundary further south than my fathers, I have added to what was bequeathed me. I am a king who speaks and acts, What my heart plans is done by my arm… Attack is valor, retreat is cowardice, A coward is he who is driven from his border. Since the Nubian listens to the word of mouth, To answer him is to make him retreat. Attack him, he will turn his back, Retreat, he will start attacking. They are not people one respects, They are wretches, craven-hearted… As for any son of mine who shall maintain this border which my majesty has made, he is my son, born to my majesty. -

Mud-Brick Architecture

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Mud-Brick Architecture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4983w678 Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Emery, Virginia L. Publication Date 2011-02-19 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California MUD-BRICK ARCHITECTURE عمارة الطوب اللبن Virginia L. Emery EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief Area Editor Material Culture University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor University of Oxford JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Emery, 2011, Mud-Brick Architecture. UEE. Full Citation: Emery, Virginia L., 2011, Mud-Brick Architecture. In Willeke Wendrich (ed.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0026w9hb 1146 Version 1, February 2011 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0026w9hb MUD-BRICK ARCHITECTURE عمارة الطوب اللبن Virginia L. Emery Ziegelarchitektur L’architecture en brique crue Mud-brick architecture, though it has received less academic attention than stone architecture, was in fact the more common of the two in ancient Egypt; unfired brick, made from mud, river, or desert clay, was used as the primary building material for houses throughout Egyptian history and was employed alongside stone in tombs and temples of all eras and regions. Construction of walls and vaults in mud-brick was economical and relatively technically uncomplicated, and mud-brick architecture provided a more comfortable and more adaptable living and working environment when compared to stone buildings. على الرغم أن العمارة بالطوب اللبن تلقت إھتماما أقل من العمارة الحجرية من قِبَل المتخصصين، فقد كانت في الواقع تلك العمارة ھي اﻷكثر شيوعا في مصر القديمة، وكان الطوب اللبن (أوالنيء) المصنوع من الطمي أو الطين الصحراوي مستخدما كمادة بناء بدائية للمنازل على مدار التاريخ المصري واستخدمت إلى جانب الحجارة في المقابر والمعابد في جميع المناطق وخﻻل جميع الفترات. -

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964)

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) Lake Nasser, Lower Nubia: photography by the author Degree project in Egyptology/Examensarbete i Egyptologi Carolin Johansson February 2014 Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University Examinator: Dr. Sami Uljas Supervisors: Prof. Irmgard Hein & Dr. Daniel Löwenborg Author: Carolin Johansson, 2014 Svensk titel: Digital rekonstruktion av det arkeologiska landskapet i koncessionsområdet tillhörande den Samnordiska Expeditionen till Sudanska Nubien (1960–1964) English title: Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) A Magister thesis in Egyptology, Uppsala University Keywords: Nubia, Geographical Information System (GIS), Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE), digitalisation, digital elevation model. Carolin Johansson, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, Box 626 SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. Abstract The Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE) was one of the substantial contributions of crucial salvage archaeology within the International Nubian Campaign which was pursued in conjunction with the building of the High Dam at Aswan in the early 1960’s. A large quantity of archaeological data was collected by the SJE in a continuous area of northernmost Sudan and published during the subsequent decades. The present study aimed at transferring the geographical aspects of that data into a digital format thus enabling spatial enquires on the archaeological information to be performed in a computerised manner within a geographical information system (GIS). The landscape of the concession area, which is now completely submerged by the water masses of Lake Nasser, was digitally reconstructed in order to approximate the physical environment which the human societies of ancient Nubia inhabited. -

Old Kingdom Epithets and Titles Related to Activities Abroad1

BRINGING TREASURES AND PLACING FEARS: OLD KINGDOM EPITHETS AND TITLES RELATED TO ACTIVITIES ABROAD1 Andrés Diego Espinel (Instituto de Lenguas y Culturas, CSIC, Madrid) ABSTRACT The present study analyses two epithets related to the Egyptian activities abroad: “who brings the produce from the foreign countries” (inn(.w) xr(y.w)t m xAs.wt) and its variants, and “who places the fear of Horus in the foreign countries” (dd(.w) nrw Hrw m xAs.wt). As with other Old Kingdom epithets, they have generally been overlooked as informative data on the administrative roles and vital experiences of their holders. In order to evaluate their potential significance as sources of information, both expressions are brought into connection with the titles of their holders and related biographical accounts. As a result, the epithets become complementary data that help to profile the actual functions and actions of these officials. For the sake of completion, certain titles related to the acquisition of intelligence are also included in this study. Moreover, further thoughts on the possible origins and values of Old Kingdom epithets are also presented RESUMEN El presente trabajo estudia dos epítetos asociados a las actividades egipcias en el extranjero: “quien trae los productos de las tierras extranjeras” (inn(.w) xr(y.w)t m xAs.wt) y otras expresiones similares, y “quien pone el terror que inspira Horus en las tierras extranjeras” (dd(.w) nrw Hrw m xAs.wt). Como otros epítetos del Reino Antiguo, éstos han sido habitualmente infravalorados como información efectiva sobre las funciones administrativas y las vivencias de quienes los detentaron. -

The Egyptian Fortress on Uronarti in the Late Middle Kingdom

and omitting any later additions. As such, it would be fair to Evolving Communities: The argue that our notion of the spatial organization of these sites and the lived environment is more or less petrified at Egyptian fortress on Uronarti their moment of foundation. in the Late Middle Kingdom To start to rectify these shortcomings, we have begun a series of small, targeted excavations within the fortress; we Christian Knoblauch and Laurel Bestock are combining this new data with a reanalysis of unpub- lished field notes from the Harvard/BMFA excavations as Uronarti is an island in the Batn el-Hagar approximately 5km well as incorporating important new studies on the finds from the Egyptian Middle Kingdom border with Kush at the from that excavation, for example that on the sealings by Semna Gorge. The main cultural significance of the island Penacho (2015). The current paper demonstrates how this stems from the decision to erect a large trapezoidal mnnw modest approach can yield valuable results and contribute fortress on the highest hill of the island during the reign of to a model for the development of Uronarti and the Semna Senwosret III. Together with the contemporary fortresses at Region during the Late Middle Kingdom and early Second Semna West, Kumma, Semna South and Shalfak, Uronarti Intermediate Period. constituted just one component of an extensive fortified zone at the southern-most point of direct Egyptian control. Block III Like most of these sites (excepting Semna South), Uronarti The area selected for reinvestigation in 2015-2016 was a was excavated early in the history of Sudanese archaeology small 150m2 part of Block III (Figure 1, Plate 1) directly by the Harvard/Boston Museum of Fine Arts mission in the to the local south of the treasury/granary complex (Blocks late 1920’s (Dunham 1967; Reisner 1929; 1955; 1960; Wheeler IV-VI) (Dunham 1967, 7-8; Kemp 1986) and to the north 1931), and was long believed to have been submerged by of the building probably to be identified as the residence of Lake Nubia (Welsby 2004). -

Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut

iii OCCASIONAL PROCEEDINGS OF THE THEBAN WORKSHOP Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut edited by José M. Galán, Betsy M. Bryan, and Peter F. Dorman Papers from the Theban Workshop 2010 2014 studies in ancient ORientaL civiLizatiOn • numbeR 69 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE of THE UNIVERSITY of CHICAgo chicagO • IllinOis v Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................. vii Program of the Theban Workshop, 2010 Preface, José M. Galán, SCIC, Madrid ........................................................................... viii PAPERS FROM THE THEBAN WORKSHOP, 2010 1. Innovation at the Dawn of the New Kingdom. Peter F. Dorman, American University of Beirut...................................................... 1 2. The Paradigms of Innovation and Their Application to the Early New Kingdom of Egypt. Eberhard Dziobek, Heidelberg and Leverkusen....................................................... 7 3. Worldview and Royal Discourse in the Time of Hatshepsut. Susanne Bickel, University of Basel ............................................................... 21 4. Hatshepsut at Karnak: A Woman under God’s Commands. Luc Gabolde, CNRS (UMR 5140) .................................................................. 33 5. How and Why Did Hatshepsut Invent the Image of Her Royal Power? Dimitri Laboury, University of Liège .............................................................. 49 6. Hatshepsut and cultic Revelries in the new Kingdom. Betsy M. Bryan, The Johns Hopkins -

The Lower Nubian Egyptian Fortresses in the Middle Kingdom: a Strategic Point of View

Athens Journal of History - Volume 5, Issue 1 – Pages 31-52 The Lower Nubian Egyptian Fortresses in the Middle Kingdom: A Strategic Point of View By Eduardo Ferreira The Ancient Egypt was a highly militarized society that operated within various theaters of war. From the Middle Kingdom period to the following times, warfare was always present in the foreign and internal policy of the pharaohs and their officers. One of these was to build a network of defensive structures along the river Nile, in the regions of the Second Cataract and in Batn el-Hagar, in Lower Nubia. The forts were relevant in both the defense and offensive affairs of the Egyptian army. Built in Lower Nubia by the pharaohs of the XII dynasty of the Middle Kingdom, these fortresses providing support to the armies that usually came from the North in campaign and allowed the ancient Egyptians to control the frontier with Kush. In fact, one of the most important features of these fortresses was the possibility to control specific territorial points of larger region which, due to it’s characteristics, was difficult to contain. Although they were built in a period of about thirty-two years, these strongholds throughout the reign of Senuseret I until the rulership of Senuseret III, they demonstrate a considerable diversification in terms of size, defenses, functions, and the context operated. They were the main reason why Egypt could maintain a territory so vast as the Lower Nubia. In fact, this circumstance is verified in the Second Intermediate Period when all the forts were occupied by Kerma, a chiefdom that araised in Upper Nubia during the end of the Middle Kingdom, especially after c. -

A Case Studies of Ancient Egyptian Architecture

International Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences (IJEAS) ISSN: 2394-3661, Volume-4, Issue-10, October 2017 A Case Studies of Ancient Egyptian Architecture Dr. Mir Mohammad Azad, Abhik Barua Abstract– Ancient Egyptian architecture is the architecture cultivated area of the Nile Valley and were flooded as the of ancient Egypt, one of the most influential civilizations river bed slowly rose during the millennia, or the mud bricks throughout history, which developed a vast array of diverse of which they were built were used by peasants as fertilizer. structures and great architectural monuments along the Nile, Others are inaccessible, new buildings having been erected on among the largest and most famous of which are the Great ancient ones. Fortunately, the dry, hot climate of Egypt Pyramid of Giza and the Great Sphinx of Giza. preserved some mud brick structures. Examples include the village Deir al-Madinah, the Middle Kingdom town at Kahun, Index Terms– Egyptian Architecture, Ancient Egypt and the fortresses at Buhen and Mirgissa. Also, many temples and tombs have survived because they were built on high I. INTRODUCTION ground unaffected by the Nile flood and were constructed of stone. Thus, our understanding of ancient Egyptian Due to the scarcity of wood, the two predominant building architecture is based mainly on religious monuments, massive materials used in ancient Egypt were sun-baked mud brick structures characterized by thick, sloping walls with few and stone, mainly limestone, but also sandstone and granite in openings, possibly echoing a method of construction used to considerable quantities. From the Old Kingdom onward, obtain stability in mud walls. -

Architecture and the Urban Environment

Architecture and the Urban Environment When Egypt had secured military and political security and vast agricultural and mineral wealth, its architecture flourished. Figure 1: A view of Buhen from the north. Buhen was an ancient fort built by Senusret III during his multiple campaigns. Its moat, drawbridges and bastions would have provided good defense against enemy attacks. The reign of Amenemhat III is especially known for its exploitation of resources, in which mining camps were operated on a semi-permanent basis. Ancient Egyptian architects used sun-dried bricks, fine sandstone, limestone and granite for their building purposes, though typically reserved stone for temples and tombs. Hieroglyphic and pictorial carvings in brilliant colors were abundantly used to decorate Egyptian structures. Workers’ villages, such as Kahun, were often built nearby to pyramid construction sites to house workers and slaves. Senusret III is known for his construction of massive forts to defend the region after his many military campaigns. The White Chapel, built by Senusret I as part of the Karnak temple complex, is one of the finest works of architecture of its time. Note: A hieroglyph is an element of an Egyptian writing system. Source URL: https://www.boundless.com/art-history/ancient-egyptian-art/middle-kingdom/architecture-and-urban-environment/ Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/ARTH110#3.3 Attributed to: Boundless www.saylor.org Page 1 of 4 Figure 2: The White Chapel The White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak is a good example of the fine quality of art and architecture produced during the 12th Dynasty. Its columns hold reliefs of a very high quality which are hardly seen elsewhere at Karnak Source URL: https://www.boundless.com/art-history/ancient-egyptian-art/middle-kingdom/architecture-and-urban-environment/ Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/ARTH110#3.3 Attributed to: Boundless www.saylor.org Page 2 of 4 As the pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom restored the country’s prosperity and stability, there was a resurgence of building projects. -

UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Amarna Period Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/77s6r0zr Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Williamson, Jacquelyn Publication Date 2015-06-24 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California AMARNA PERIOD ﻋﺼﺮ اﻟﻌﻤﺎرﻧﺔ Jacquelyn Williamson EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor University of Oxford WOLFRAM GRAJETZKI Area Editor Time and History University College London JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Williamson, 2015, Amarna Period. UEE. Full Citation: Williamson, Jacquelyn, 2015, Amarna Period. In Wolfram Grajetzki and Willeke Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002k2h3t 8768 Version 1, June 2015 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002k2h3t AMARNA PERIOD ﻋﺼﺮ اﻟﻌﻤﺎرﻧﺔ Jacquelyn Williamson Amarna Zeit Période d’Amarna The reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten/Amenhotep IV is controversial. Although substantial evidence for this period has been preserved, it is inconclusive on many important details. Nonetheless, the revolutionary nature of Akhenaten’s rule is salient to the modern student of ancient Egypt. The king’s devotion to and promotion of only one deity, the sun disk Aten, is a break from traditional Egyptian religion. Many theories developed about this era are often influenced by the history of its rediscovery and by recognition that Akhenaten’s immediate successors rejected his rule. ﺗﻌﺘﺒﺮ ﻓﺘﺮة ﺣﻜﻢ اﻟﻤﻠ��ﻚ اﺧﻨ��ﺎﺗﻮن / أﻣﻨﺤﻮﺗ��ﺐ اﻟﺮاﺑﻊ ﻣﻦ اﻟﻔﺘﺮات اﻟﻤﺜﯿﺮة ﻟﻠﺠ��ﺪل ، وﻋﻠﻰ اﻟﺮﻏﻢ ﻣﻦ وﺟﻮد أدﻟﺔ ﻗﻮﯾﺔ ﻣﺤﻔﻮظﺔ ﺗﺸ���ﯿﺮ إﻟﻰ ﺗﻠﻚ اﻟﺤﻘﺒﺔ اﻟﺘﺎرﯾﺨﯿﺔ ، إﻻ اﻧﮭﺎ ﻏﯿﺮ ﺣﺎﺳ���ﻤﺔ ﻟﻌﺪد ﻣﻦ اﻟﺘﻔﺎﺻ���ﯿﻞ اﻟﻤﮭﻤﺔ ، وﻣﻊ ذﻟﻚ ، ﻓﺈن اﻟﻄﺒﯿﻌﺔ اﻟﺜﻮرﯾﺔ ﻟﺤﻜﻢ اﻟﻤﻠﻚ اﺧﻨﺎﺗﻮن ھﻲ اﻟﺸ������ﺊ اﻟﻤﻠﺤﻮظ واﻟﺒﺎرز ﻟﻠﻄﺎﻟﺐ اﻟﺤﺪﯾﺚ ﻓﻲ ﻣﺼ����ﺮ اﻟﻘﺪﯾﻤﺔ. -

Ancient Core-Periphery Interactions: Lower Nubia During Middle Kingdom Egypt (Ca

ANCIENT CORE-PERIPHERY INTERACTIONS: LOWER NUBIA DURING MIDDLE KINGDOM EGYPT (CA. 2050-1640 B.C.)1 Roxana Flammini Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Universidad Católica Argentina [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper applies the core-periphery theoretical framework as an attempt to explain the nature of the Egyptian intervention in Lower Nubia and the subsequent sociopolitical status the region acquired during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2050-1640 BC) through consideration of the ideological bias held by the Egyptian State along with its economic and political goals. INTRODUCTION Since the publication of The Modern World System the categories that Wallerstein (1974) generated in order to explain the emergence of capitalism in Western Europe have been tested to describe pre-modern world-systems. Critical observations made to the original model – like those of Schneider (1977) – and theoretical accommodations to particular historical situations also began a few years after the publication of the original theory. In fact, Wallerstein’s three assumptions: of core dominance on the peripheries; of inherently asymmetrical exchange between regions; and of trade as the prime mover of social development could not always be proven to take place in pre-modern societies. Several of these theoretical approaches were related to the ancient Near Eastern polities’ relationships (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1991; Kardulias 1996; Kohl 1987; Rowlands 1987; Stein 1999). In particular, Rowlands (1987) called attention to the anachronisms that could arise in the applications of these categories to non-capitalist societies and proposed an analysis based on the exchange of luxuries rather than staples. Kohl (1987), on the other hand, argued that multiple core areas co-existed and made direct contact with each other.