The Lower Nubian Egyptian Fortresses in the Middle Kingdom: a Strategic Point of View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three “Italian” Graffiti from Semna and Begrawiya North

Eugenio Fantusati THREE “ITALIAN” GRAFFITI FROM SEMNA AND BEGRAWIYA NORTH Egyptian monuments are known to bear texts and composed of soldiers, explorers, merchants and, signatures engraved by Western travelers who in the second wave clerics, was quite consider- thus left traces of their passage on walls, columns able. For a long time the call of the exotic and of and statues beginning after the Napoleonic ex- adventure drew many Italians to Africa. In the pedition. early 19th century, they had no qualms about Sudan, although less frequented, did not leaving a fragmented country, not only governed escape this certainly depreciable practice. Indeed, by foreign powers, but also the theatre of bloody none of the European explorers in Batn el-Hagar wars for independence. Their presence in Africa avoided the temptation to leave graffiti on grew progressively to such an extent that Italian, archaeological sites, as if there was some myster- taught in Khartoum’s missionary schools, became ious force pushing them to this act, undeniable the commercial language of the Sudan. For a long because visible, once they had reached their so time, it was employed both in the official docu- longed-for destination. ments of the local Austrian consulate and in the Even George Alexander Hoskins, antiquarian, Egyptian postal service before being definitely writer and excellent draftsman, who openly supplanted by French after the opening of the condemned the diffusion of the practice to deface Suez Canal (Romanato 1998: 289). monuments, admitted his own “guilt” in this Naturally, the many Italians visiting archae- respect: “I confess on my first visit to the Nile, ological sites in Nubia did not refrain from I wrote my name on one of the colossal statues in leaving graffiti just like the other Europeans. -

Kvinner I Det Gamle Egypt

Kvinner i det gamle Egypt Ein komparativ studie Avbiletinga viser ei kvinne som sit ute i det fri og sel fruktene frå ein sykamorebusk med eit barn tett til brystet. Ein ser såleis den komplekse naturen til kvinnerolla; På den eine sida som mor og omsorgsperson, og på den andre som kvinne med eige ressursgrunnlag og høve for eiga inntekt. Masteravhandling i antikk historie. Institutt for arkeologi, historie, kunst og religionsvitenskap. Universitetet i Bergen, våren 2009 Reinert Skumsnes Kvinner i det gamle Egypt FØREORD Eit masterstudium, ei avhandling og ei lang reise i tid og stad er til endes. Reisa har vore interessant, mykje takka rettleiaren min, professor Jørgen Christian Meyer. Hans lange fartstid og gode kunnskapar som historikar har hjelpt meg ut av mang ei fortvilt stund kor kvinnene i det gamle Egypt rett og slett ikkje ville same veg som meg. Både Christian og fyrsteamanuensis Ingvar Mæhle skal ha takk for låge dørstokkar, velvilje og solid, jordnær profesjonalitet. Frå det norske egyptologimiljøet takkar eg professor emeritus Richard H. Pierce (UiB), professor Saphinaz-Amal Naguib (UiO), Pål Steiner (UiB), Anders Bettum (UiO) og Vidar Edland for større og mindre bidrag, som alle har vore viktige. Likeeins vil eg gje ei stor takk til alle medstudentane mine som til ei kvar tid har vore tilgjengelege og positive i kaffikroken vår på Sydneshaugen. Arbeidet har vore omfattande, men likevel overkommeleg. Dei fleste kjeldene har allereie vore jobba mykje med, og har såleis skapt større rom for drøfting og utvida fagleg innsikt. Ei spesiell takk må eg her sende til professor Anthony Spalinger, professor Doborah Sweeeney, professor Andrea McDowell, og professor Schafik Allam som alle har vore villige til å svare på spørsmål eg har hatt knytt til deira arbeid med kjeldene. -

No. 6 a NEWSLETTER of AFRICAN ARCHAEOLOGY May 19 75 Edited

- No. 6 A NEWSLETTER OF AFRICAN ARCHAEOLOGY May 1975 Edited by P.L. Shinnie and issued from the Department of Archaeology, The University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta T2N lN4, Canada. (This issue edited by John H. Robertson.) I must apologize for the confusion which has developed con- cerning this issue. A notice was sent in February calling for material to be sent by March 15th. Unfortunately a mail strike in Canada held up the notices, and some people did not receive them until after the middle of March. To make matters worse I did not get back from the Sudan until May 1st so the deadline really should have been for the end of April. My thanks go to the contributors of this issue who I am sure wrote their articles under pressure of trying to meet the March 15th deadline. Another fumble on our part occurred with the responses we received confirming an interest in future issues of Nyame Akuma Professor ~hinnie'sintent in sending out the notice was to cull the now over 200 mailing list down to those who took the time to respond to the notice. Unfortunately the secretaries taking care of the-mail in Shinnie's absence thought the notice was only to check addresses, and only changes in address were noted. In other words, we have no record of who returned the forms. I suspect when Professor Shinnie returns in August he will want to have another go at culling the mailing list . I hope this issue of Nyame Akuma, late though it is, reaches everyone before they go into the field, and that everyone has an enjoyable and productive summer. -

The Semna South Project Louis V

oi.uchicago.edu The Semna South Project Louis V. Zabkar For those who have never visited the area of southern Egypt and northern Sudan submerged by the waters of the new Assuan High Dam, and who perhaps find it difficult to visualize what the "lake" created by the new Dam looks like, we include in this report two photographs which show the drastic geographic change which oc curred in a particular sector of the Nile Valley in the region of the Second Cataract. Before the flooding one could see the Twelfth Dynasty fortress; and, next to it, at the right, an extensive predominantly Meroitic and X-Group cemetery; the characteristic landmark of Semna South, the "Kenissa," or "Church," with its domed roof, built later on within the walls of the pharaonic fortress; the massive mud-brick walls of the fortress; and four large dumps left by the excavators—all this can be seen in the photo taken at the end of our excavations in April, 1968. On our visit there in April, 1971, the fortress was completely sub merged, the mud-brick "Kenissa" with its dome having collapsed soon after the waters began pounding against its walls. One can see black spots in the midst of the waters off the center which are the stones on the top of the submerged outer wall of the fortress. The vast cemetery is completely under water. In the distance, to the north, one can clearly see the fortress of Semna West, the glacis of which is also sub- 41 oi.uchicago.edu The area of Semna South included in our concession The Semna South concession submerged by the waters of the "lake 42 oi.uchicago.edu merged, and the brick walls of which may soon collapse through the action of the risen waters. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

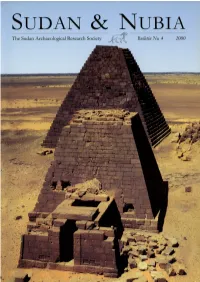

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Buhen in the New Kingdom

Buhen in the New Kingdom George Wood Background - Buhen and Lower Nubia before the New Kingdom Traditionally ancient Egypt ended at the First Cataract of the Nile at Elephantine (modern Aswan). Beyond this lay Lower Nubia (Wawat), and beyond the Dal Cataract, Upper Nubia (Kush). Buhen sits just below the Second Cataract, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite modern Wadi Halfa, at what would have been a good location for ships to carry goods to the First Cataract. The resources that flowed from Nubia included gold, ivory, and ebony (Randall-MacIver and Woolley 1911a: vii, Trigger 1976: 46, Baines and Málek 1996: 20, Smith, ST 2004: 4). Egyptian operations in Nubia date back to the Early Dynastic Period. Contact during the 1st Dynasty is linked to the end of the indigenous A-Group. The earliest Egyptian presence at Buhen may have been as early as the 2nd Dynasty, with a settlement by the 3rd Dynasty. This seems to have been replaced with a new town in the 4th Dynasty, apparently fortified with stone walls and a dry moat, somewhat to the north of the later Middle Kingdom fort. The settlement seems to have served as a base for trade and mining, and royal seals from the 4th and 5th Dynasties indicate regular communications with Egypt (Trigger 1976: 46-47, Baines and Málek 1996: 33, Bard 2000: 77, Arnold 2003: 40, Kemp 2004: 168, Bard 2015: 175). The latest Old Kingdom royal seal found was that of Nyuserra, with no archaeological evidence of an Egyptian settlement after the reign of Djedkara. -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Part IV Historical Periods: New Kingdom Egypt to the Death of Thutmose IV End of 17Th Dynasty, Egyptians Were Confined to Upper

Part IV Historical Periods: New Kingdom Egypt to the death of Thutmose IV End of 17th dynasty, Egyptians were confined to Upper Egypt, surrounded by Nubia and Hyksos → by the end of the 18th dynasty they had extended deep along the Mediterranean coast, gaining significant economic, political and military strength 1. Internal Developments ● Impact of the Hyksos Context - Egypt had developed an isolated culture, exposing it to attack - Group originating from Syria or Palestine the ‘Hyksos’ took over - Ruled Egypt for 100 years → est capital in Avaris - Claimed a brutal invasion (Manetho) but more likely a gradual occupation - Evidence says Hyksos treated Egyptians kindly, assuming their gods/customs - Statues of combined godes and cultures suggest assimilation - STILL, pharaohs resented not having power - Portrayed Hyksos as foot stools/tiptoe as unworthy of Egyptian soil - Also realised were in danger of being completely overrun - Kings had established a tribune state but had Nubians from South and Hyksos from North = circled IMMEDIATE & LASTING IMPACT OF HYKSOS Political Economic Technological - Administration - Some production - Composite bow itself was not was increased due - Horse drawn oppressive new technologies chariot - Egyptians were - Zebu cattle suited - Bronze weapons climate better - Bronze armour included in the - Traded with Syria, - Fortification administration Crete, Nubia - Olive/pomegranat - Modelled religion e trees on Egyptians - Use of bronze - Limited instead of copper = disturbance to more effective culture/religion/d -

Egypt and Nubia

9 Egypt and Nubia Robert Morkot THE, EGYPTIAN E,MPIRE,IN NUBIA IN THE LATE, BRONZE AGE (t.1550-l 070B CE) Introdu,ct'ion:sef-def,nit'ion an,d. the ,irnperi.ol con.cept in Egypt There can be litde doubt rhat the Egyptian pharaohs and the elite of the New I(ngdom viewed themselvesas rulers of an empire. This universal rule is clearly expressedin royal imagerv and terminology (Grimal f986). The pharaoh is styied asthe "Ruler of all that sun encircles" and from the mid-f 8th Dynasry the tides "I(ing of kings" and "Ruler of the rulers," with the variants "Lion" or "Sun of the Rulers," emphasizepharaoh's preeminence among other monarchs.The imagery of krngship is of the all-conquering heroic ruler subjecting a1lforeign lands.The lcingin human form smiteshis enemies.Or, asthe celestialconqueror in the form of the sphinx, he tramples them under foot. In the reigns of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten this imagery was exrended to the king's wife who became the conqueror of the female enemies of Egypt, appearing like her husbandin both human and sphinx forms (Morkot 1986). The appropriateter- minology also appeared; Queen Tiye became "Mistress of all women" and "Great of terror in the foreign lands." Empire, for the Egyptians,equals force - "all lands are under his feet." This metaphor is graphically expressedin the royal footstools and painted paths decorated \Mith images of bound foreign rulers, crushed by pharaoh as he walked or sar. This imagery and terminologv indicates that the Egyptian attirude to their empire was universally applied irrespective of the peoples or countries. -

CV 2 Purdue Research Foundation Research Grant, Purdue University (Research Assistantship), 2016-2017

Michele Rose Buzon Department of Anthropology Purdue University 700 W. State Street West Lafayette, IN 47907-2059 [email protected] (765) 494-4680 (tel)/(765) 496-7411 (fax) http://web.ics.purdue.edu/~mbuzon tombos.org ACADEMIC POSITIONS Full Professor, Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, 2017-present Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, 2010-2017. Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, 2007-2010. Instructor, Honours Thesis Supervisor, Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary, 2006-2007. Postdoctoral Fellow, Instructor, Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta, 2004-2006. Teaching Associate, Department of Anthropology, UCSB, 2004. Teaching Assistant, Department of Anthropology, UCSB, 2001, 2002. Laboratory Manager, Biological Anthropology Laboratory, Loyola University Chicago, 1996-1998. RESEARCH INTERESTS Bioarchaeology, Paleopathology, Culture Contact, Biological and Ethnic Identity, Environmental Stress, Isotope Analysis, Nubia, Egypt EDUCATION Killam Postdoctoral Fellowship, Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta, 2004-2006. Project: “Strontium Isotope Analysis of Migration in the Nile Valley.” Supervisors: Dr. Nancy Lovell, Dr. Sandra Garvie-Lok. Ph.D. in Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2004. Dissertation: “A Bioarchaeological Perspective on State Formation in the Nile Valley.” Supervisor: Dr. Phillip L. Walker M.A. in Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2000. Supervisor: Dr. Phillip L. Walker B.S. Honors in Anthropology, Magna Cum Laude, Loyola University Chicago, 1996. August 2019 RESEARCH AWARDS Purdue University College of Liberal Arts Discovery Excellence Award, 2018 Purdue University Lu Ann Aday Award, 2017 Purdue University Faculty Scholar, Purdue University, 2014-2019. EXTRAMURAL FUNDING Senior Research Grant, BCS-1916719, National Science Foundation Archaeology ($60,810), 2019-2022. Collaborative Research: Assessing the Impact of Holocene Climate Change on Bioavailable Strontium Within the Nile River Valley. -

Hyksos, Egipcios, Nubios: Algunas Consideraciones Sobre El I1 Pe~Odointermedio Y La Convivencia Entre Los Distintos Grupos Etnicos

HYKSOS, EGIPCIOS, NUBIOS: ALGUNAS CONSIDERACIONES SOBRE EL I1 PE~ODOINTERMEDIO Y LA CONVIVENCIA ENTRE LOS DISTINTOS GRUPOS ETNICOS Inmaculada Vivas SBinz Universidad de AlcalB de Henares ABSTRACT This article reviews some questions of the political and social history of the the Second Intermediate Period. The first part is based on recent discussion about the terminology related to the period, and the convenience or unconvenience of using certain terms in future investigations. The second part concerns the relationships among the dlflerent ethnic groups living in Egypt at that time, and the process of acculturation of the Hyksos in Egypt. An interesting hypotheses about king Nehesy is analysed, which proposes the existence of a dynastic marriage between a Nubian queen and a king of the XIVth Dynasty, both being the suppoused parents of Nehesy. I reject this hypotheses on the basis of archaedogical and epigraphical sources. The true origin of Nehesy remains a moot point, being still d~ficultto explain why this king had a name meaning "the Nubian". -Los estudios sobre el I1 Periodo Intermedio egipcio se remontan a1 siglo pasado', pero es desde hace apenas unas dCcadas cuando se ha sentido la necesidad de definir ese tCrmino. Los primeros trabajos sobre el tema eran breves anilisis sobre el final del Reino Medio y la llegada de 10s hyksos, sobre Cstos y su relaci6n con Israel, o la posible ubicaci6n de Avaris y el proceso de expulsi6n de 10s hyksos. Todos estos estudios son importantes para nuestras investigaciones pero muchas veces se basan s610 en fuentes arqueol6gicas procedentes de Siria-Palestina de las cuales se extrapolaban datos para la situaci6n de Egipto. -

Egypt and Africa Presentation.Pdf

Egypt and Africa Map of the Second Cataract showing fortress area Different plan types of Nubian fortresses: Cataract fortresses Plains fortresses Fortress at Buhen: Plains Fortress Defensive Characteristics Askut: Cataract Fort Middle Kingdom institutions as shown by seal impressions First Semna Stela of Senwosret III Southern boundary, made in the year 8, under the majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Khakaure Senwosret III who is given life forever and ever; in order to prevent that any Nubian should cross it, by water or by land, with a ship or with any herds of the Nubians, except a Nubian who shall come to do trading in Iqen (Mirgissa) or with a commission. Every good thing shall be done with them, but without allowing a ship of the Nubians to pass by Heh, going downstream, forever. Boundary Stela of Senwosret III from Semna (a duplicate found at Uronarti) “…I have made my boundary further south than my fathers, I have added to what was bequeathed me. I am a king who speaks and acts, What my heart plans is done by my arm… Attack is valor, retreat is cowardice, A coward is he who is driven from his border. Since the Nubian listens to the word of mouth, To answer him is to make him retreat. Attack him, he will turn his back, Retreat, he will start attacking. They are not people one respects, They are wretches, craven-hearted… As for any son of mine who shall maintain this border which my majesty has made, he is my son, born to my majesty.