Mud-Brick Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LILY COX-RICHARD Sculptures the Size of Hailstones 17 February - 12 May 2018

LCR: In this show, I’m using found objects and sculptures I’ve made and The 2018 Cell Series is generously supported by trying to put them in positions where they can slip between multiple McGinnis Family Fund of Communities Foundation of Texas systems. In addition to lightning rods and scrap copper, I’m working on with additional funding from new sculptures that could fit in your hand. The “hail scale” is used to Susie and Joe Clack measure the size of hailstones by comparing them to common objects like Gene and Marsha Gray a walnut, golf ball, or teacup: hailstones the size of ____. Your earlier Amy and Patrick Kelly questions about context are really important here—what might be enor- mous for a hailstone might be a very modest size for a sculpture. Talking Sally and Robert Porter about the weather is often considered banal, but lately, the weather has been urgently claiming a lot more space for discussion. What happens when we ignore an important conversation or dismiss small talk (or small Past Cell Series artists: sculptures)? I’m interested in zooming in on details and giving them a lot DENNY PICKETT - 2008 | JEFFREY BROSK - 2009 | RANDY BACON - 2009 of space and attention. JOHN FROST - 2009 | NANCY LAMB - 2010 | JOHN ROBERT CRAFT - 2010 TERRI THORNTON - 2010 | ANNE ALLEN - 2011 | WILL HENRY - 2011 The sculptures the size of hailstones will sit on a large plaster plinth that ERIC ZIMMERMAN - 2011 | BILL DAVENPORT - 2012 | JUSTIN BOYD - 2012 has woven basket forms embedded in it, forming niches and craters. Often CAROL BENSON - 2012 | KANA HARADA - 2013 | BRAD TUCKER - 2013 pedestals and plinths are made to blend into their surroundings; but of ANTHONY SONNENBERG - 2013 | CHRIS SAUTER - 2014 course, they can never disappear. -

Cleopatra II and III: the Queens of Ptolemy VI and VIII As Guarantors of Kingship and Rivals for Power

Originalveröffentlichung in: Andrea Jördens, Joachim Friedrich Quack (Hg.), Ägypten zwischen innerem Zwist und äußerem Druck. Die Zeit Ptolemaios’ VI. bis VIII. Internationales Symposion Heidelberg 16.-19.9.2007 (Philippika 45), Wiesbaden 2011, S. 58–76 Cleopatra II and III: The queens of Ptolemy VI and VIII as guarantors of kingship and rivals for power Martina Minas-Nerpel Introduction The second half of the Ptolemaic period was marked by power struggles not only among the male rulers of the dynasty, but also among its female members. Starting with Arsinoe II, the Ptolemaic queens had always been powerful and strong-willed and had been a decisive factor in domestic policy. From the death of Ptolemy V Epiphanes onwards, the queens controlled the political developments in Egypt to a still greater extent. Cleopatra II and especially Cleopatra III became all-dominant, in politics and in the ruler-cult, and they were often depicted in Egyptian temple- reliefs—more often than any of her dynastic predecessors and successors. Mother and/or daughter reigned with Ptolemy VI Philometor to Ptolemy X Alexander I, from 175 to 101 BC, that is, for a quarter of the entire Ptolemaic period. Egyptian queenship was complementary to kingship, both in dynastic and Ptolemaic Egypt: No queen could exist without a king, but at the same time the queen was a necessary component of kingship. According to Lana Troy, the pattern of Egyptian queenship “reflects the interaction of male and female as dualistic elements of the creative dynamics ”.1 The king and the queen functioned as the basic duality through which regeneration of the creative power of the kingship was accomplished. -

Sunt Bark Powder: Alternative Retanning Agent for Shoe Upper Leather Manufacture

International Journal of Advance Industrial Engineering E-ISSN 2320 –5539 ©2018 INPRESSCO®, All Rights Reserved Available at http://inpressco.com/category/ijaie/ Research Article Sunt Bark Powder: Alternative Retanning Agent for Shoe Upper Leather Manufacture * ^* # M.H Abdella , A.E Musa and S.B Ali #Department of Leather Engineering, School of Industrial Engineering and Technology, Sudan University of Science and Technology, Khartoum – Sudan ^Department of Leather Technology, College of Applied and Industrial Sciences, University of Bahri, Khartoum – Sudan Received 01 April 2018, Accepted 01 June 2018, Available online 05 June 2018, Vol.6, No.2 (June 2018) Abstract The retanning process is a very important step in leather manufacturing because it overcomes some of the disadvantages of chrome tannage and it can contributes to further stabilization of collagen fibers and good handle of leather, such as fullness, softness, elasticity and so on. In order to meet customers’ requirements, a wide variety of retanning agents are used in retanning process viz. vegetable tan and phenolic synthetic/organic tanning materials. Sunt bark, widely distributed in Sudan, has been evaluated for its utilization in the retanning of the leathers. In the present investigation, sunt bark powder has been used for the retanning of wet blue leathers. The effectiveness sunt bark in retanning of wet blue leathers has been compared with wattle retanning. The organoleptic properties of the leathers viz. softness, fullness, grain smoothness, grain tightness (break), general appearance, uniformity of dyeing of sunt bark retanned leather have been evaluated in comparison with wattle retanned leathers. Sunt retanning resulted in leathers with good grain tightness. -

Cairo-Luxor-Aswan-Ci

Cairo, Luxor & Aswan City Package 6 Days – 5 Nights Daily Arrivals Motorboating on the Nile, Aswan Limited to 12 participants Day 3: Cairo / Luxor to see the Temple of Isis and the Aswan High Early morning flight to Luxor; transfer to Dam. Optional extra night in Aswan is available; Tour Includes: your hotel. Morning tour the Valley of the please inquire. Overnight in Aswan. (B.L) • Flights within Egypt as per Itinerary Kings containing the secretive tombs of New Kingdom Pharaohs; enter the Tomb Day 5: Aswan / Cairo • Choice of Deluxe Hotel Plans c Return flight to Cairo. Balance of day at ai • Meals: Buffet Breakfast Daily, of Tutankhamen. Continue to the famed leisure, or take an optional tour to Abu , and R 3 Lunches. 1 Dinner on the Nile Colossi of Memnon Temple of Queen Hatshepsut. After lunch, visit the vast Simbel (See Page 23 for details). Overnight o, • All Transfers as indicated Karnak Temple-Complex, Avenue of the in Cairo. (B) l • Sightseeing with Egyptologist Guide uxo Sphinxes and the imposing Temple of Day 6: En Route by Exclusive IsramBeyond Services Luxor. Evening: Optional Sound & Light • All Entrance Fees to Sites as indicated Show at the Temple of Karnak ($75 per Transfer to the airport for your departure flight. R • Visa for Egypt (USA & Canadian person based on 2 participants, please (B) & Passports only) reserve at time of booking). (B.L) EXTEND YOUR STAY! a Day 4: Luxor / Edfu / Aswan Optional extra night in Aswan is swan Highlights: Depart Luxor driving to the Temple of Horus highly recommended; or extend • Panoramic “Cairo by Night” Tour & at Edfu, the best preserved of all large your tour to Sharm el-Sheikh on Dinner on the Nile Egyptian temples before continuing to the Red Sea, Alexandria, Jordan or c • Entrance to one of the Great Pyramids Aswan, Egypt’s southernmost city. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

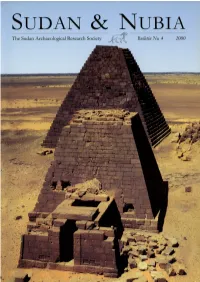

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Making Mudbricks: Science and Technology Challenge!

Making Mudbricks: Science and Technology Challenge! Building with Mud and Stone Soil (mud) has been used to build things for thousands of years. Soil is almost everywhere. This means it is easy to find. When mixed with water and other materials it can be used in lots of ways. The big problem with buildings made from mud is that they can be easily damaged and need regular repair. Most buildings in ancient Amarna were made from mudbrick. Only the most important parts of the city – like the temples – were made of stone. The stone was cut into small blocks called talatat at the nearby quarries. The blocks were designed to be carried by one strong person. Look back at the measuring challenge to figure out how big a talatat block was. It measured one cubit long by half a cubit wide and half a cubit thick. Do you think you would be strong enough to carry one? Mudbricks were used to build all the houses at ancient Amarna, even the house of the King! Mudbricks were much thinner and lighter than stone blocks and varied in size depending on how they were made. At Amarna, mudbricks measured about 34cm long, 17cm wide and 8cm thick. Soil from near the river Nile made the best mudbricks. The mud was mixed with sand and gravel from the desert and water was added to help hold it together. The wet mudbrick mix was then put into a rectangular wooden mould to give it the right shape. The mould was then lifted off the brick which was left in the sun to dry. -

Buhen in the New Kingdom

Buhen in the New Kingdom George Wood Background - Buhen and Lower Nubia before the New Kingdom Traditionally ancient Egypt ended at the First Cataract of the Nile at Elephantine (modern Aswan). Beyond this lay Lower Nubia (Wawat), and beyond the Dal Cataract, Upper Nubia (Kush). Buhen sits just below the Second Cataract, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite modern Wadi Halfa, at what would have been a good location for ships to carry goods to the First Cataract. The resources that flowed from Nubia included gold, ivory, and ebony (Randall-MacIver and Woolley 1911a: vii, Trigger 1976: 46, Baines and Málek 1996: 20, Smith, ST 2004: 4). Egyptian operations in Nubia date back to the Early Dynastic Period. Contact during the 1st Dynasty is linked to the end of the indigenous A-Group. The earliest Egyptian presence at Buhen may have been as early as the 2nd Dynasty, with a settlement by the 3rd Dynasty. This seems to have been replaced with a new town in the 4th Dynasty, apparently fortified with stone walls and a dry moat, somewhat to the north of the later Middle Kingdom fort. The settlement seems to have served as a base for trade and mining, and royal seals from the 4th and 5th Dynasties indicate regular communications with Egypt (Trigger 1976: 46-47, Baines and Málek 1996: 33, Bard 2000: 77, Arnold 2003: 40, Kemp 2004: 168, Bard 2015: 175). The latest Old Kingdom royal seal found was that of Nyuserra, with no archaeological evidence of an Egyptian settlement after the reign of Djedkara. -

Improved Adobe Mudbrick in Application – Child-Care Centre Construction in El Salvador

13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering Vancouver, B.C., Canada August 1-6, 2004 Paper No. 705 IMPROVED ADOBE MUDBRICK IN APPLICATION – CHILD-CARE CENTRE CONSTRUCTION IN EL SALVADOR Dominic DOWLING1 SUMMARY Major earthquakes in Latin America, Asia and The Middle East have served as recent reminders of the vulnerability of traditional adobe (mudbrick) dwellings to the force of earthquakes. A host of research, training and construction projects continue to address this precarious situation and there have been various publications describing the developments in improved adobe (mudbrick) design and construction in recent years. These publications have mostly originated from research institutions and have tended to focus on the technical and experimental details of a variety of improvement systems. The dissemination of this important information is a vital component in the challenge to promote and build safer homes. Furthermore, these advances in technical detail must be accompanied by practical information, which relates to the actual application of the proposed systems, addressing the advantages and disadvantages of each technique. This paper attempts to address the current deficiency of this practical information, and thus provide adobe constructors and proponents with a realistic understanding of some of the practical issues related to improved adobe construction. This paper describes the technical and practical aspects and ‘lessons learned’ from a recent improved adobe construction project in El Salvador, as well as drawing on field investigations, laboratory research and other literature. The paper concludes with a proposed addition to the current technical evaluation of the performance of improvement systems: the assessment of the skill level and resources required to effectively incorporate improved adobe systems. -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

0.00 Download Free

This is an Open Access publication. Visit our website for more OA publication, to read any of our books for free online, or to buy them in print or PDF. www.sidestone.com Check out some of our latest publications: ANALECTA PRAEHISTORICA LEIDENSIA 45 98163_APL_45_Voorwerk.indd I 16/07/15 13:00 98163_APL_45_Voorwerk.indd II 16/07/15 13:00 ANALECTA PRAEHISTORICA LEIDENSIA PUBLICATION OF THE FACULTY OF ARCHAEOLOGY LEIDEN UNIVERSITY EXCERPTA ARCHAEOLOGICA LEIDENSIA EDITED BY CORRIE BAKELS AND HANS KAMERMANS LEIDEN UNIVERSITY 2015 98163_APL_45_Voorwerk.indd III 16/07/15 13:00 Series editors: Corrie Bakels / Hans Kamermans Editor of illustrations: Joanne Porck Copyright 2015 by the Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden ISSN 0169-7447 ISBN 978-90-822251-2-9 Subscriptions to the series Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia can be ordered at: P.J.R. Modderman Stichting Faculty of Archaeology P.O. Box 9514 NL-2300 RA Leiden The Netherlands 98163_APL_45_Voorwerk.indd IV 16/07/15 13:00 Contents The stable isotopes 13C and 15N in faunal bone of the Middle Pleistocene site Schöningen (Germany): statistical modeling 1 Juliette Funck Thijs van Kolfschoten Hans van der Plicht ‘Trapping the past’? Hunting for remote capture techniques and planned coastal exploitation during MIS 5 at Blombos Cave and Klasies River, South Africa 15 Gerrit L. Dusseldorp Geeske H.J. Langejans A Late Neolithic Single Grave Culture burial from Twello (central Netherlands): environmental setting, burial ritual and contextualisation 29 Lucas Meurkens Roy van Beek Marieke Doorenbosch Harry -

Lesson #1: Architecture Features Through the Ages

Unit Two: History of Architecture and Building Codes Lesson #1: Architecture Features Through the Ages Objectives Students will be able to… . Summarize the architecture features through Stone Ages to Neo-Classical Time. Common Core Standards LS 11-12.6 RSIT 11-12.2 RLST 11-12.2 Problem Solving/Critical Thinking 5.4 Health and Safety 6.2, 6.3, 6.4, 6.5, 6.6, 6.12 Technical Knowledge and Skills 10.1, 10.2, 10.3 Residential and Commercial Construction Pathway D2.1, D2.8, D2.9, D3.1, D3.2, D3.3, D3.4, D3.7 Responsibility and Leadership 7.4, 9.3 Materials Architecture Features Through the Ages Power Point https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn%3Aaaid%3Ascds%3AUS%3Ab4f485df -0d78-4fa9-9509-0b9ea3e1952c Architecture Features Through the Ages Worksheet Lesson Sequence . Introduce to students that a specific architectural style is characterized by a collection of design details. These details include size and shape of windows, the size and placement of a porch, and the presence or absence of columns. Review the Architecture Features Through the Ages PowerPoint with students. Have students fill in the Architecture Features Through the Ages Worksheet while reviewing the power point. Discuss and answer any questions students may have along the way. © BITA: A program promoted by California Homebuilding Foundation BUILDING INDUSTRY TECHNOLOGY ACADEMY: YEAR TWO CURRICULUM Assessment Check for understanding while presenting PowerPoint. Grade student worksheets. Reteach and clarify any misunderstandings as needed. Accommodations/Modifications Check for Understanding One on One Support Peer Support Extra Time If Needed © BITA: A program promoted by California Homebuilding Foundation BUILDING INDUSTRY TECHNOLOGY ACADEMY: YEAR TWO CURRICULUM Architecture Features Through the Ages Worksheet As you watch the PowerPoint on Architectural Features Through the Ages fill in summary with the correct answers. -

The Black Wattle in Hawaii and Recommend the Same for Publication As Bulle Tin No

HAWAII AQRICULTVRAL EXPERIMENT STA'I'IO!i. :J. G. SI\IITH, SPECIAJ:, AGENT IN CHARGE. BULLETIN No. 11. ·THE BLACK·WATTLE (Acacia c!eCUt'f,ens) IN HAWAII. BY JARED G. SMITH, SPECIAL AGENT IN CHARGE, HAWAII AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION. UNDER THE. _Sl,l'ERVISION .. OJ' OF'F_ICE OF EXPERIMENT STP.TIONS, U.S. !)epartment ofAgriculture. WASHINGTON: :: ·--<: ;,: .. '~. -- .'. GOVERN~IENT PRI)'<TING. OFFICE: 1996. 863 HAWAII AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION. J. G. SMITH, SPECIAL AGENT IN CHARGE. BULLETIN No. 11. 'THE BLACK WATTLE (Acacia decurrens) IN HA\VAII. BY JARED G. SMITH, SPECIAL AGENT IN CHARGE, HAWAII AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION. UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF OFFICE OF EXPERIMENT STATIONS, U. S. Department ofAgriculture. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. I 9 06. HAWAII AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION, HONOLULU. [Under the supervision of A. C. TRuE; Director of the Office of Experiment Stations, United States Department of Agriculture.] STATION STAFF. JARED G. SMITH, Special, Agent in Charge. D. L. VAN DINE, Entomotogist. EDMUND C. SHOREY, Chemist. J.E. HIGGINS, Horticulturist. F. G. KRAUSS, In Charge of Rice Investigations. Q. Q. BRADFORD, Farm Foreman. C. R; BLACOW; In Charge ofTobacco Experiments (P. 0., Paauilo, Hawaii). \2) LETTER OF TRANSMITl'AL. HONOLULU, HAWAII, January 1, 1906. Sm: I have the honor to transmit herewith a paper on The Black Wattle in Hawaii and recommend the same for publication as Bulle tin No. 11 of the Hawaii Agricultural Experiment Station. Very respectfully, JARED G. SMITH, Special Agent in Charge, Hawaii Agricultural Experiment Station. Dr. A. C. TRUE, Director, Office of Experiment Stations, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, D. 0.